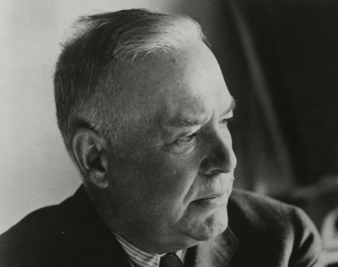

SYLVIA SALMIWallace Stevens

SYLVIA SALMIWallace Stevens

In the fall of 1936, after a decade of not doing so, this magazine sponsored a poetry prize. Of the 1,800 poems submitted, said the editors of The Nation, “the overwhelming majority were concerned with contemporary social conflicts either at home or abroad.” The winning poem, Wallace Stevens’s “The Men That Are Falling,” was an elegy for soldiers recently killed in the Spanish Civil War, which reads, in part:

Taste of the blood upon his martyred lips,

O pensioners, O demagogues and pay-men!

This death was his belief though death is a stone,

This man loved earth, not heaven, enough to die.

These stand among the most uncharacteristic lines that Stevens ever published. Coming upon them in the elegantly compressed compass of the new Selected Poems, it’s difficult to imagine that the author of a quietly unnerving pentameter like “The river that flows nowhere, like a sea” could have written the line “Taste of the blood upon his martyred lips.”

Yet to read “The Men That Are Falling” beside some of the greatest poems of the twentieth century–“The Snow Man,” “A Postcard From the Volcano,” “The River of Rivers in Connecticut”–is to be forced to rearticulate the extremely complex terms of Stevens’s achievement. Stevens stands simultaneously among the most worldly and the most otherworldly of American poets, and it is paradoxically through his otherworldliness–through poems whose plain-spoken diction feels spooky–that his respect for the actual world is registered. What is uncharacteristic about “The Men That Are Falling” is not the desire to write about a controversial war; Stevens often did that. What distinguishes the poem is the unconvincingly urgent rhetoric in which that desire is registered.

Stevens was born in Reading, Pennsylvania, in 1879. After attending Harvard College and New York Law School, he began working in the insurance industry in 1908. He quickly became one of the country’s foremost experts in surety law, and in 1934 he was named vice president of the Hartford Accident and Indemnity Company. “The truth is that we may well be entering an insurance era,” he wrote in “Insurance and Social Change,” published in 1937, the year in which the first Social Security benefits were paid. Surveying the nationalized insurance schemes of Italy, Germany and Britain, Stevens tried to convince his colleagues that the Social Security Administration posed no threat to their business or their personal lives.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Other great modern American poets had full-time jobs. Marianne Moore was an editor, William Carlos Williams a doctor, T.S. Eliot a banker (and later an editor). What distinguishes Stevens is that he never gave the impression of feeling any tension between the different aspects of his life. Once he quipped that “money is a kind of poetry,” but more often he emphasized that his legal work was in no way poetic, just as his poems were not meaningfully involved with the logics of law or economics. In an essay called “Surety and Fidelity Claims,” he even admitted that his work would seem tedious to almost anyone: “You sign a lot of drafts. You see surprisingly few people. You do the greater part of your work either in your own office or in lawyers’ offices. You don’t even see the country; you see law offices and hotel rooms.” Unlike Ezra Pound, who was an amateur economist, Stevens had a professional’s sense of the limitations of expertise. He resembles in this regard George Oppen, who stopped writing poetry for over twenty years in order to devote himself to personal and social problems that poetry did not have the power to ameliorate, however implicated in such problems poetry might have been.

Stevens also experienced extended periods of silence. At Harvard he was the president of The Advocate, a prestigious literary magazine; he exchanged sonnets with the philosopher George Santayana, for whom he would later write “To an Old Philosopher in Rome.” But after leaving Cambridge in 1900, he wrote no poems for almost a decade. And when the magisterial “Sunday Morning” appeared in 1915, in Poetry magazine, it seemed to have come from nowhere; almost no apprentice work preceded it.

Stevens’s first book, Harmonium, appeared eight years later, when the poet was 44, and it is still the most astonishing debut in the history of American poetry. In contrast, the poems in Pound’s A Lume Spento or Williams’s Poems barely let us glimpse the great work to come. But after publishing Harmonium, Stevens gave up poetry for another decade. His daughter, Holly, was born. “My job is not now with poets from Paris,” he told Williams, who was a close friend. “It is to keep the fire-place burning and the music-box churning and the wheels of the baby’s chariot turning.”

Anyone who cared about American poetry presumed that Stevens’s career as a poet was finished, but then “The Idea of Order at Key West” suddenly appeared in 1934. Beginning at age 55, Stevens finally assumed the profile of a poet, and the great books of his maturity (Ideas of Order, The Man With the Blue Guitar, Parts of a World, Transport to Summer and The Auroras of Autumn) were published at regular intervals. He continued working at the Hartford until well after the age of mandatory retirement; he declined an invitation to be the Charles Eliot Norton Professor of Poetry at Harvard. Shortly before his death in 1955, his Collected Poems received both the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize.

One of his last poems was “The River of Rivers in Connecticut”:

There is a great river this side of Stygia,

Before one comes to the first black cataracts

And trees that lack the intelligence of trees.

In that river, far this side of Stygia,

The mere flowing of the water is a gayety,

Flashing and flashing in the sun. On its banks,

No shadow walks. The river is fateful,

Like the last one. But there is no ferryman.

He could not bend against its propelling force.

It is not to be seen beneath the appearances

That tell of it. The steeple at Farmington

Stands glistening and Haddam shines and sways.

It is the third commonness with light and air,

A curriculum, a vigor, a local abstraction…

Call it, once more, a river, an unnamed flowing,

Space-filled, reflecting the seasons, the folk-lore

Of each of the senses; call it, again and again,

The river that flows nowhere, like a sea.

The river of rivers feels mythic, as momentous as the river that separates us from the afterlife. But this decidedly earthly river is not crossed only once; we need no ferryman, no Charon, to carry us over. The river is fateful because every moment of human life is fateful. It flows through the familiar towns of Haddam and Farmington, its water flashes in the sun. It is an emblem of our mortality, an endless flowing, but more important it embodies a sweet acceptance of oblivion: the river carries us nowhere, not like the sea but like a sea–like any sea at all.

Stevens once remarked that while we possess the great poems of heaven and hell, the great poems of the earth remain to be written. Both “The River of Rivers in Connecticut” and “The Men That Are Falling” are products of Stevens’s lifelong ambition to write such poems–poems that honor mortality without needing to look beyond it. But even as “The Men That Are Falling” disdains the extremities of heaven and hell, it embraces earth in a language of fitful extremity: “This death was his belief though death is a stone,/This man loved earth, not heaven, enough to die.” In contrast, the consolation of “The River of Rivers in Connecticut” feels enticingly complex because the poem’s diction is so eerily generalized, its syntax so quietly declarative. The poem’s celebration of human limitation would not feel convincing if its tone did not make small means feel magical.

This tone is Stevens’s great achievement, his most enduring response to the world. Some poems seem relevant because of what they say, because of their subject matter. But all poems are truly relevant, whatever they say, because their manner of saying seduces us to inhabit the poem’s language as if it were our own–despite the fact that any great poet’s language is witheringly idiosyncratic. We feel, reading a great poem, that a small corner of the soul has for a moment become public property. Stevens describes this feeling with uncanny abruptness in “The House Was Quiet and the World Was Calm,” a poem that makes the act of reading and the act of writing feel indistinguishable: “The reader became the book.”

Stevens first became himself in one of the earliest poems reprinted in the Selected Poems. “The Death of a Soldier” was written in response to the letters of Eugène Lemercier, a French soldier who was killed in World War I, but it feels as if the poem could be about anyone.

Death is absolute and without memorial,

As in a season of autumn,

When the wind stops,

When the wind stops and, over the heavens,

The clouds go, nevertheless,

In their direction.

The cycles of the natural world cannot stop to record Lemercier’s death; the clouds go nevertheless in their direction, which can’t be specified, because it’s theirs, not ours. For Stevens, there is immense consolation in this disregard for an individual human life–an assurance that the natural world will prevail despite the human appetite for destruction. The language of Stevens’s most characteristic poetry partakes, in small ways, of this consolation: “The Death of a Soldier” does not mention Lemercier, who has already disappeared.

Stevens did not always write with the incandescent plainness that distinguishes poems from “The Death of a Soldier” to “The River of Rivers in Connecticut.” Sometimes he is a poet of extravagant verbal energy, a show-off who indulges in lines like “Chieftain Iffucan of Azcan in caftan/Of tan with henna hackles, halt!” And sometimes he is more celebrated for such showiness than for the austerity that more truly becomes him. Stevens himself thought that the interplay of plainness and fanciness (or what he called reality and imagination) was central to his work, and he placed a programmatic account of this interplay at the center of “Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction,” a long poem that asks to be treated as a masterpiece:

Two things of opposite natures seem to depend

On one another, as a man depends

On a woman, day on night, the imagined

On the real. This is the origin of change.

“Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction” is an enactment of this notion; the poem oscillates between an imperative to perceive the world plainly and a complementary imperative to imagine the world extravagantly. We need continually to create “fictions” that explain our world, and we need, as our world changes, to wipe such fictions away, returning to a plain sense of things that is itself an imaginative achievement. “In the absence of a belief in God,” said Stevens in one of his most willed moments of self-confidence, “the mind turns to its own creations and examines them, not alone from the aesthetic point of view, but for what they reveal, for what they validate and invalidate.”

This quasi-philosophical aspect of Stevens seemed very attractive in the later decades of the twentieth century, especially after the death of Eliot, whose Christianity sometimes inflected the academic critical establishment that championed his poems. Today this aspect of Stevens feels threadbare–as if the professional lawyer came to imagine that he was also a professional philosopher. I don’t find what Stevens called his “reality-imagination complex” very engaging, and neither does John Serio, who says in his introduction to the Selected Poems that while many of the longer poems “do spur us intellectually,” they “may not move us emotionally.” Serio sees Stevens primarily as a lyric poet, and while he has excluded some of the longer poems from his selection (“Extracts From Addresses to the Academy of Fine Ideas,” “Examination of the Hero in a Time of War,” “The Pure Good of Theory”), I have trouble imagining the house growing quiet enough for even a devoted reader of “Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction” to become the book.

At issue here is not a preference for shorter poems; at issue is the particular kind of language that most authentically constitutes Stevens’s gift.

Clear water in a brilliant bowl,

Pink and white carnations. The light

In the room more like a snowy air,

Reflecting snow. A newly-fallen snow

At the end of winter when afternoons return.

Pink and white carnations–one desires

So much more than that.

This opening stanza of “The Poems of Our Climate” begins in an idiom that mirrors the stillness of the scene described, but when Stevens says that one desires “so much more” than an arrangement of pink and white carnations, the poem takes a peculiar turn. I’m convinced that Stevens thought he should desire more, but I’m not sure he actually did. His deepest inclination was (to quote the one phrase in the poetry that sounds like it was written by an insurance executive) to remain “within what we permit.” So when Stevens reaches for sensual exuberance (“Chieftain Iffucan of Azcan in caftan”) or passionate commitment (“Taste of the blood upon his martyred lips”) or philosophical profundity (“Two things of opposite natures seem to depend/On one another”), the language often seems willed, as if the poet were embarrassed by his own taste for deprivation. “Is it bad to have come here/And to have found the bed empty?” asks Stevens in a little poem called “Gallant Château.” The answer, undeflected by the wish to be different from oneself, is “It is good.”

In the poems that matter most, this question needs neither to be asked nor answered: the language carries its own conviction. Early Stevens–“The Snow Man”:

One must have a mind of winter

To regard the frost and the boughs

Of the pine-trees crusted with snow.

Midcareer Stevens–“The Man With the Blue Guitar”:

It is the sea that whitens the roof.

The sea drifts through the winter air.

It is the sea that the north wind makes.

The sea is in the falling snow.

Late Stevens–“The Course of a Particular”:

Today the leaves cry, hanging on branches swept by wind,

Yet the nothingness of winter becomes a little less.

It is still full of icy shades and shapen snow.

These poems, like any of Stevens’s best poems, make deprivation feel seductively like plenitude.

All the best poems are preserved in this collection, a culling that is considerably more severe than that of the selected volume it supersedes, The Palm at the End of the Mind, edited by Holly Stevens and published in 1972. The whole of Stevens is represented here–the plain, the fancy, the philosophical–but the latter two categories have been pruned, affording the best of Stevens more prominence. This winnowing is over time inevitable (nobody reads the whole of Wordsworth or Tennyson), and I would go further: it’s hard to imagine a need to reinhabit “Description Without Place” (“It is possible that to seem–it is to be”) or “Late Hymn From the Myrrh-Mountain” (“Unsnack your snood, madanna”). Without the distraction of this willed language, the greatest of Stevens’s poems, the movingly stark poems written during the last five years of his life, stand out even more vividly as the culmination of his career:

No soldiers in the scenery,

No thoughts of people now dead,v As they were fifty years ago:

Young and living in a live air,

Young and walking in the sunshine,v Bending in blue dresses to touch something–

Today the mind is not part of the weather.

Some readers might prefer the fanciful or the philosophical; others might argue that austerity cannot fully exist without its complements. But when we hear the sound of Stevens in poems by subsequent poets, it is most often the music of austerity, at once worldly and otherworldly, that we hear. Mark Strand: “From the shadow of domes in the city of domes,/A snowflake, a blizzard of one, weightless, entered your room.” Louise Glück: “I can’t hear your voice/for the wind’s cries, whistling over the bare ground.” Donald Justice: “In a hotel room by the sea, the Master/Sits brooding.” Carl Phillips: “The wind’s pattern was its own, and the water’s also.” To say that these lines are indebted to Stevens is like saying that fish are indebted to water: the sound of Stevens has entered the sound of poetry in the language.