Major League Baseball faces a crisis that could lead to its first lockout or strike in 25 years. The last strike began on August 12, 1994, and continued for 232 days, forcing the cancellation of the World Series and the first three weeks of the 1995 season. The current collective bargaining agreement doesn’t expire until after the 2021 season. But as fans gather to watch the World Series this October, the Major League Baseball Players Association (MLBPA) and the team owners have already begun meeting.

Some of the issues in contention—including minimum salaries, the number of years a team may “own” a player before he can sign with another team, and how revenue sharing among teams is spent to the detriment of players—led to strikes or owner lockouts in the past. For the first time in decades, players are talking openly about the possibility of another strike if the owners continue to exploit the serious shortcomings in the current contract.

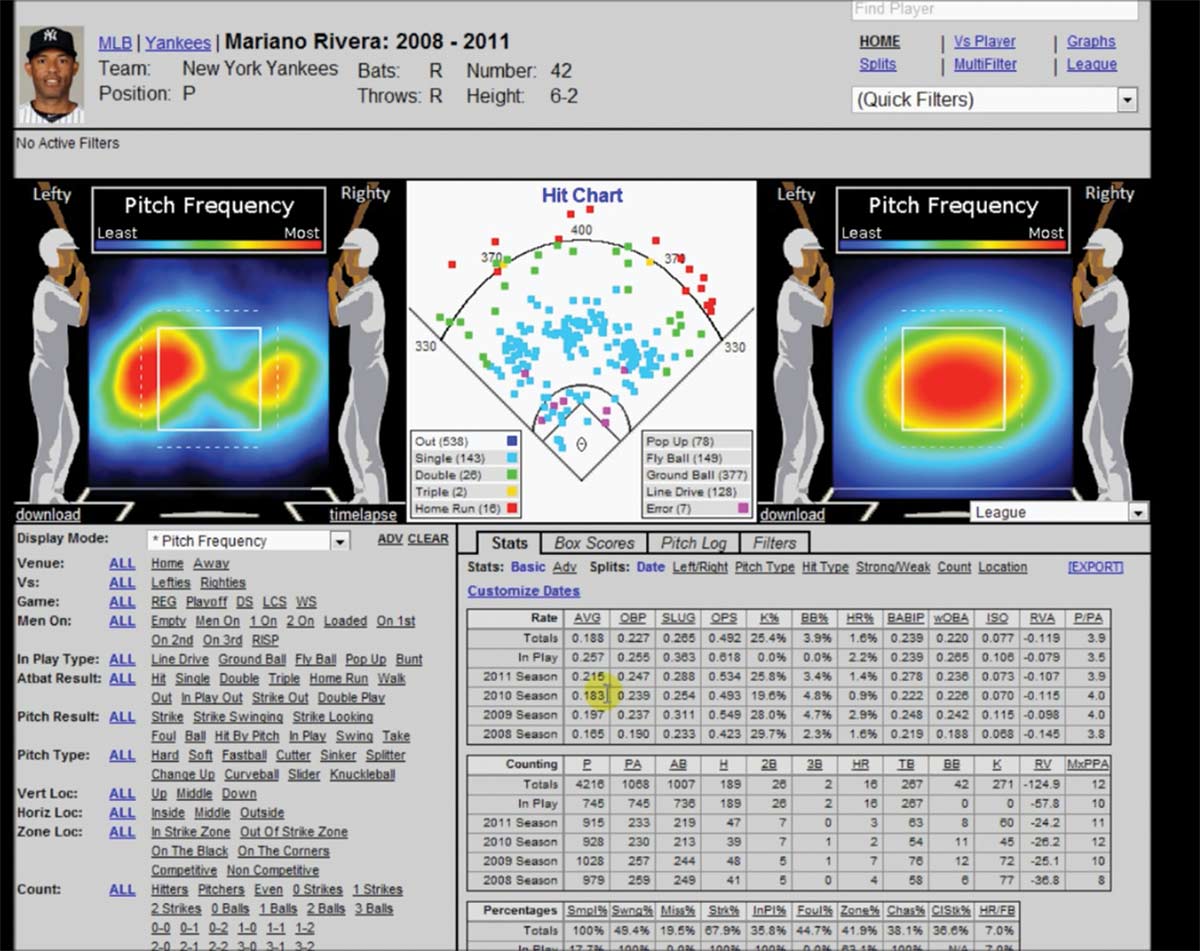

One key factor is the owners’ increasing use of analytics—sophisticated statistical metrics—to calculate a player’s value to the team and negotiate his salary accordingly. While many players believe that analytics can help improve their on-field performance, others remain skeptical.

“Put a computer on the mound and see if it will throw strikes, or put it at the plate and see if it can hit a fastball,” said future Hall of Famer Albert Pujols in the Los Angeles Angels’ locker room after a Labor Day weekend game. The Angels had just beaten the Boston Red Sox, the current World Series champions, with the 39-year-old Pujols contributing two hits and three RBIs.

“I don’t change my approach just because of analytics. I use the same approach that I’ve had since Day 1, when I was in St. Louis [playing with the Cardinals],” said Pujols, who is in his 19th major league season. “You have to work your butt off every day and don’t take anything for granted.”

Others worry that the analytics revolution has provided owners and general managers with a weapon to devalue players’ contributions. Traditionally they were paid based on past performance. If a player did well during the previous two or three years, he could expect a significant increase in salary that reflected his contribution.

Now players are typically paid based on anticipated performance. By analyzing so-called age curves, which supposedly show that a player’s productivity generally declines after he reaches his early 30s, owners and general managers have adopted a kind of reverse seniority: The older you are, the less valuable you are.

In the late 1970s, writer Bill James pioneered the use of statistical data to determine why teams win and lose, an approach he called sabermetrics—with a nod to the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR)—and which a new generation of business-school-trained baseball executives now calls analytics.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

The Oakland Athletics were one of the first major league teams to embrace analytics. As recounted in the 2011 movie Moneyball (based on Michael Lewis’s 2003 book of the same name), Billy Beane, the Athletics’ general manager, was having a hard time fielding a competitive ball club against teams with much bigger budgets for player salaries. With the help of a Yale economics graduate, he used statistical analysis to find undervalued players whom other teams had overlooked—providing new opportunities for players who thought their careers were over. Despite his team’s budget constraints, Beane took the Oakland A’s to the playoffs every year from 2000 through 2003.

Moneyball celebrated the fine-grained parsing of players’ hitting, pitching, and defensive tendencies as a tool to field winning teams. Analytics proponents hoped to see baseball become more scientific, embracing big data and eschewing the intuition and gut feelings of old-time baseball scouts and managers.

While baseball has always been a game of numbers—batting average, earned run average, fielding percentage, fastball speed—the slicing and dicing of player performance has expanded exponentially. Baseball is now among the most surveilled occupations. Pitchers get printouts of spin rates measuring how fast the ball is rotating and arm-slot graphs showing when the ball is released. Batters are given launch angle stats, which measure the vertical angle at which the ball leaves the bat.

Angels infielder David Fletcher said he particularly appreciates an analytic figure called the chase rate, which tracks how often pitchers get batters to swing at bad throws. This helps make him a more disciplined hitter, he said.

Analytics helped Boston Red Sox pitcher Matt Barnes, who said he was struggling at the start of last season. Cameras and computers showed him the length of his stride while pitching and the way the ball was spinning out of his hand. “We weren’t doing it from just a visual perspective,” he said. “We had factual numbers, as opposed to the coaches sitting there watching and saying, ‘That looks good.’”

Most players have embraced the analytics revolution because they believe it helps them improve their performance—and because of pressure to do so by insistent general managers. Others still chafe at the idea that it might determine their professional destiny.

Wins Above Replacement (WAR), one of the most widely used statistics, purports to measure the number of additional wins a player is worth over the course of the season, beyond the contribution of an average (replacement) player. Owners and general managers use WAR to measure players’ productivity and value.

“Nowadays, just about everything seems to be analytics,” said Los Angeles Angels pitcher and alternate union representative Cam Bedrosian, whose father, Steve Bedrosian, won the 1987 National League Cy Young Award. “Maybe they are putting that [analytics] over the human element.”

Will Smith, a rookie catcher for the Los Angeles Dodgers, also expressed doubts about computer modeling. “Everyone in [the locker room] is confident in themselves that they can hit anything, even if the computers say they can’t. And most guys in here will prove the computer wrong,” he said.

Even former Angels manager Brad Ausmus, who caught for four major league teams from 1993 to 2010, understands that while analytics has changed every aspect of the game—from which players are signed to how they prepare for games—there are severe limits to evaluating players primarily by numbers.

“Analytics can’t capture the heart of a player, the ability of a player to step up in a big situation, the ability of a player to control his emotions,” he said just before a game against the visiting Red Sox. “It can’t rate work ethic. It can’t analyze the importance of a player to a clubhouse culture.”

Initially, analytics allowed general managers like Beane to spot the untapped potential in inexpensive players and to help on-field managers decide whom to play, where, and when. But if Moneyball’s narrative was all about opportunity, team owners and general managers have since turned that happy fable upside down. They now utilize analytics to undervalue players while pocketing the money that previously went to the men on the field.

Unlike several decades ago, when most general managers came from the ranks of major league players and field managers, few of today’s top executives have ever played pro ball, much less on big league rosters. Farhan Zaidi, the president of baseball operations for the San Francisco Giants, has a PhD in economics from the University of California at Berkeley, Minnesota Twins general manager Thad Levine earned an MBA from UCLA, and Chicago White Sox general manager Rick Hahn has an MBA from Northwestern and a law degree from Harvard. Eleven of Major League Baseball’s 30 GMs have degrees from Ivy League universities, and others went to such elite schools as Stanford and MIT. Every major league team now has an analytics department, with specialists trained in business, economics, and statistics.

For their part, major league players had long lived in a state of virtual indentured servitude—until they hired Marvin Miller, a former steelworkers’ union official, to serve as the MLBPA’s first full-time executive director in 1966. Before Miller, who served in that capacity until 1982, players had no rights to determine the conditions of their employment. Contracts were limited to one year, but they reserved the team’s right to retain the player for the next year. Before the start of each season, the team owners essentially told players, “Take it or leave it.”

Under Miller’s leadership, players gained leverage by joining forces against the owners, including strikes in 1972 and 1981. Those strikes, along with two more in 1985 and 1994 to ‘95, led to increased salaries, binding arbitration, good pensions, a share of television revenue, improvements in travel conditions, and better training and medical treatment.

Players won their biggest victory in 1976, when an independent arbiter granted them the right to become free agents at the end of their contracts, allowing them to choose which team they’d play for, veto proposed trades, and bargain for the best contract—all cornerstones of an economic free market. Since 1966, the minimum player salary has jumped from $6,000 a year (or $46,000 in today’s dollars) to $555,000 in 2019, and the average salary from $19,000 (or $147,000 today) to $4.5 million in 2018.

In recent years, however, owners have weakened the advantages of free agency, which kicks in after players have spent six years in the majors. Clubs have stopped making offers to players consistent with their performance in prior seasons. Instead, baseball’s owners and general managers have embraced an economic logic to keep the salaries of younger players low while squeezing those of talented but not superstar-level older players. Instead of receiving raises based on past performance, many seasoned players have been forced to sign short-term or even minor league contracts.

For example, All-Star Mike Moustakas, who as of late September had 182 career home runs, had to settle for a one-year deal with the Milwaukee Brewers after seven years with the Kansas City Royals. Ten-year veteran outfielder Gerardo Parra, who had a .284 batting average for the Colorado Rockies last year, had to sign a minor league contract with the Giants in February because his weighted metrics did not rate highly enough compared with other hitters’ over three years. After he was released by the Giants, Parra became a free agent and signed with the Washington Nationals, making the MLB minimum salary.

Despite being an All-Star pitcher, Dallas Keuchel, a free agent, had to wait more than two months after the current season started to sign a one-year deal with the Atlanta Braves. Younger players and those approaching free agency are watching what’s happening to their teammates and seeing their own future.

While players are reluctant to use the C-word—collusion—their current grievances are exacerbated by the suspicion that the owners have been working in concert to limit players’ opportunities in free agency. History suggests that those suspicions are justified. In 1990, for example, a neutral arbiter ruled that the owners had engaged in illegal collusion and would have to pay $280 million to the aggrieved players.

David Samson, the president of the Miami Marlins from 2002 to 2017, said that “youth and inexpensiveness is the elixir of success.” But the owners’ elixir has become the players’ poison.

The average career length for a major league player is a little over four years. Rather than sign players to long-term contracts, teams increasingly view them as contingent workers who can be shuttled between short stints in the major and minor leagues, similar to employees in the growing gig economy. Last year 1,270 players appeared in major league games—an all-time high since Major League Baseball first fielded 30 teams in 1998. But the vast majority of those players will never reach the six-year threshold for free agency, when they can put their talents on the open market and allow every team to bid for them.

In another trend that mirrors dynamics in the larger economy, baseball is generating more productivity from its lowest-paid players. The proportion of players making the minimum MLB salary or slightly more has gone up significantly since 2014. This year, over 40 percent of players earned somewhere between the $545,000 minimum and $599,500. New York Yankees slugger Aaron Judge is in his third full year in the big leagues and won’t be eligible for free agency until 2023. He’s among the best hitters in the game but is earning $684,300 a year—much lower than his true value to the team.

Before the 2019 season, a few elite players made headlines for their astronomical long-term contacts. Manny Machado, who played for the Dodgers last year, signed a 10-year, $300 million contract with the San Diego Padres. All-Star outfielder Bryce Harper signed a similar deal with the Philadelphia Phillies, for 13 years at $330 million.

In fact, only a handful of players on each team make the kind of eye-popping salaries that skew the average. Although the average annual salary is $4.5 million, the median is $1.5 million. The best-paid one-quarter of players earn three-quarters of total salaries.

From an owner’s or general manager’s perspective—or any factory manager’s, for that matter—if the analytics tell you that a younger, cheaper worker not yet eligible for free agency gives you similar or greater productivity in terms of his contribution to wins, why would you overpay the older worker? If you can obtain significant WAR from Yankees slugger Judge but pay him far less than his value as a free agent, what owner wouldn’t leap at the chance? In fact, clubs are significantly underpaying him and many other players before they reach free agency.

According to Sonoma State University professor Willie Gin, the analytics revolution allows team owners “to pay less for the same productivity because of the very precision and scope of big data’s behavioral profiling.” He writes that Beane “is celebrated as a crafty manager rather than an exploiter of underpaid baseball labor.”

The way Dodgers star pitcher Clayton Kershaw sees it, free agency and the salary structure need to be fixed. As he told USA Today during this year’s All-Star break, “We’ve got to find a way to get these [younger] guys paid during their peak years if they’re not going to be rewarded on the way out.”

Kershaw’s anger is pervasive among players. According to third baseman Justin Turner, the players’ union representative for the Dodgers, analytics can be used for good or evil. Analytics has “done wonders” for the Dodgers, he said, but there is also a downside. “You might see guys hitting .240 or .250 but are hammering the ball all over the place. The front office will sit you down and show you how productive your at-bats are. But that doesn’t necessarily mean they are going to go into an arbitration case or free agency and fight for you to give you more money.”

Another key issue is how the team owners are spending revenue-sharing money. MLB’s revenue-sharing formula is essentially a redistribution of wealth among owners, requiring teams in larger markets to send money to those in smaller ones. Last year, for example, the Yankees and the Dodgers were among the teams that made net contributions to the revenue-sharing pool. On the other end, teams like the Marlins, the Tampa Bay Rays, and the Pittsburgh Pirates received money from the pool.

But since the owners do not have to fully open their books to the players’ union—or anyone else—the MLBPA suspects that they’re cutting back salaries by claiming to be rebuilding their teams. The players view such language as a euphemism for increasing profits for the owners alone.

Before the 2018 season, the Marlins slashed their payroll by trading perhaps the best outfield in the majors, selling Giancarlo Stanton to the Yankees, Marcell Ozuna to the St. Louis Cardinals, and Christian Yelich to the Milwaukee Brewers. Obviously, cutting the payroll saves money—but it also means that fans aren’t seeing their favorite team field the best talent available.

Los Angeles Angels pitcher Bedrosian observed, “The big thing is just integrity of play—making sure all the teams are putting the best players on the field.” Having the best players “makes the game better,” said the Red Sox’s Barnes, the team’s union representative, “and it makes a better experience for the fans. We saw a little bit of a struggle [over free agency] in the off-season and even at the beginning of the season.”

The current collective bargaining agreement stipulates that teams’ revenue-sharing money has to be spent improving on-field performance, but the language is vague enough to allow owners to spend it on technological investments while skimping on player salaries, including free-agent talent.

Before this season, for example, the Marlins spent $15 million on improvements to their 37,000-seat, taxpayer-subsidized ballpark, even though they only attracted an average of 10,013 fans to their home games in 2018. Absent top-notch ballplayers, the new amenities did little to sustain fans’ interest. The Marlins finished last in their division.

The MLBPA has filed grievances against four teams—the Athletics, the Marlins, the Pirates, and the Rays—claiming they inappropriately spent their revenue-sharing money.

During the 19th century, engineer Frederick Winslow Taylor revolutionized corporate management by using time and motion studies to help employers gain greater control over workers’ bodies in the name of profit-making efficiencies. A baseball field is not a factory—far from it. But many players express ambivalence about MLB’s version of Taylorism. According to Dodgers pitcher Ross Stripling, analytics “can help you in negotiations, but it’s also a tool that [owners and general managers] can use against you.”

“It seems every day now someone is making up a new analytic tool to devalue players, especially free agents,” said Giants third baseman Evan Longoria, a 12-year veteran and three-time All-Star, in an Instagram post this past January. “As players we need to stand strong for what we believe we are worth and continue to fight for the rights we have fought for time and time again.”

“Without the union,” Barnes observed, “what we have now would be nothing.”

Each time the players went on strike in the past, the team owners and most baseball writers insisted that baseball would be ruined as a popular sport. Each time they were proved wrong. In 1967, attendance at MLB games averaged 15,005. Last year, it was 28,830, according to the league.

Meanwhile, the value of every major league team has skyrocketed. In 2004, Arturo Moreno purchased the Angels for $184 million; that franchise is now estimated to be worth $1.9 billion. The Yankees are worth $4.6 billion, the most among the 30 teams.

MLB’s billionaire owners include the Angels’ Moreno (worth $3.4 billion), the Athletics’ John Fisher ($2.5 billion), the Dodgers’ Mark Walter ($3.3 billion), the Giants’ Charles Johnson ($5 billion), the Red Sox’s John Henry ($2.7 billion), and the Detroit Tigers’ Marian Ilitch ($3.7 billion).

League revenues have also been increasing steadily, reaching a record-breaking $10.3 billion in 2018—a trend that has been consistent for 16 years. Rather than stifle baseball’s prosperity, the union simply gave players—many of them from poor and working-class families, with roughly a third now coming from outside the United States—the power to win a greater share of their employers’ growing revenue. But according to Smith College economist Andrew Zimbalist, the author of several books on baseball’s finances, the players’ share of the teams’ total revenue has been declining in recent years.

When calculating operating income, Zimbalist said, team owners exclude most of their ancillary income from team-owned and -branded hotels and other venues near the ballparks. These profits are not counted in the team’s revenue stream or considered part of the profits from baseball operations. For example, the Cubs own a hotel with a gym near Wrigley Field that benefits from the team’s brand as well as the location, and the Braves’ parent company, Liberty Media, owns a major hotel and other real estate developments that surround the team’s new ballpark. None of these revenues are considered baseball operations, even though without baseball, they arguably wouldn’t exist.

The players’ union will try to rectify some of these dynamics in the current round of negotiations. One way would be to raise the minimum salary substantially to reflect the greater productivity—or increased WAR numbers—of younger and pre-free-agency players. This would also help restore the value of free agency for players who are not superstars, making them more attractive and affordable by comparison. The union will continue to oppose a salary cap, which the owners have wanted for years. But baseball’s so-called luxury tax, which penalizes teams whose combined player salaries exceed a certain amount, acts as a disincentive to put money into salaries.

Reducing the years required before free agency or arbitration kicks in would also help, as would more explicit contract language on how the teams’ revenue-sharing money is spent.

Ordinary fans may find it difficult to sympathize with ballplayers whose starting salary is $555,000, even if the typical player spends only four years in the majors. But what’s happening in baseball is not that different from what’s going on in the work lives of most Americans. Corporate profits have been climbing, while the share going to workers has failed to keep up. From 1978 to 2018, the compensation of corporate CEOs grew by 1,008 percent, far outstripping S&P stock market growth (707 percent); over the same period, wages for the typical worker grew by just 11.9 percent, according to a new study by the Economic Policy Institute.

When baseball players go on strike, it isn’t out of greed but out of the same fundamental labor relations principles as any worker.

Still, as the contract situation heats up over the coming year, there are a number of things the MLBPA could do to help improve the union’s image with the general public. For starters, it could stand with workers engaged in other union drives, as well as campaigns for living-wage laws in the cities where they play. Major League Baseball needs fans who make enough money to afford the increasing cost of tickets, parking, and hot dogs at the stadiums.

The MLBPA should make sure that players aren’t forced to cross other unions’ picket lines—as both the Yankees and Dodgers did last year at Boston hotels where workers were on strike. It would have been a significant gesture for a few Yankees, Dodgers, and Red Sox players to show up and join the hotel workers’ picket lines. One way to avoid putting major league players in this embarrassing situation would be to insert language in their union contract that requires teams to stay in union hotels and prohibits them from staying in hotels where the workers are in the midst of labor disputes with management. (Only three of the 26 cities with major league teams—Cincinnati, Tampa, and Arlington, Texas—don’t have union hotels.)

Boston’s hotel strikers pointed out that Marriott International uses analytics to track how much time housekeepers spend in every single room they clean. The cult of efficiency, the pressure to produce, and the means of surveillance are everywhere.

The MLBPA could support emerging efforts to unionize minor league ballplayers, who currently earn an estimated $7,500 a year and get paid only during the baseball season. Most of these players will never climb into the better-paying majors.

This year, the MLBPA tried but could not stop the New Era Cap Company, which makes caps for all major league players, from closing its union factory near Buffalo and moving production to nonunion facilities in Florida and overseas. In an op-ed in The Washington Post, Washington Nationals pitcher Sean Doolittle expressed his concern that he and other players “will be wearing caps made by people who don’t enjoy the same labor protections and safeguards that we do.” The MLBPA could insist that teams purchase players’ uniforms, bats, and other equipment from union companies—or at least from those that provide decent pay, working conditions, and benefits.

If baseball players think strategically and lend a hand to workers who are struggling, the boys of summer just might provide some inspiration to the broader labor movement—and to the country.