Alt-right and assorted racist groups have canceled plans to march in Boston and eight other cities tomorrow, because, say the organizers of #MarchOnGoogle, they’ve received “credible alt-left terrorist threats.” They nevertheless hope to regroup and march “in a few weeks’ time.” (They’re outraged at Google for firing an employee who ripped its efforts to increase gender and racial diversity.) But whenever and in whatever form white racists gather again, the mainstream news media need to resist their every instinct to talk mush and passively imply that “both sides” are at fault, as some media initially did over Charlottesville.

It’s true that for most of this week nearly every news outlet this side of Fox and Breitbart has put responsibility for the death, injuries, and violence in Charlottesville squarely on the white nationalists. The press has been even more adamant in calling out Trump since his “off the rails” news conference on Tuesday, when he defended the “fine people” on “both sides,” and conjured an “alt left” threatening those who “innocently” just want to protest the removal of Confederate monuments. But, in the immediate aftermath of Charlottesville last Saturday, too much of the respectable press offered up the kind of muddled headlines that could allow low-information news consumers—as I was that day—to believe that, yep, both sides are at fault, or worse.

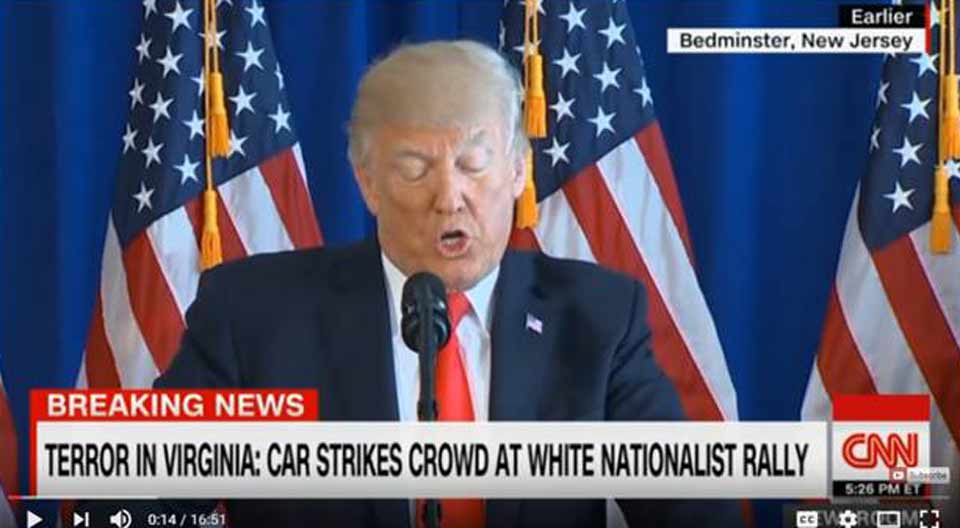

I was busy and distracted that afternoon, but from what little cable news I had glanced at, it seemed as if an antiracism protester had driven a car into a crowd of white nationalists, killing a woman and injuring many more. This confused me—surely the good guys wouldn’t be so stupid as to hand Nazis the gift of martyrdom, but that seemed a real possibility. I caught only bits of what the pundits were angrily talking about, but the CNN chyron remained steady: “terror in virginia: car strikes crowd at white nationalist rally.”

There was this at 4:24 pm ET (via Mediaite):

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

And the same an hour later:

It wasn’t until late that night, after I had the time to learn more, that I realized it was a white nationalist who plowed a car into antiracist protesters and killed a woman. I wasn’t the only one who had inverted who did what to whom. On Sunday, my 19-year-old son told me that he and a friend had heard about an anti-KKK activist crashing his car into a bunch of Klanners.

It wasn’t “fake news” or bot-generated memes that created this opposite-day effect. It was simply the news ambiguously delivered.

And if I, who write about media, could get this so wrong, so could millions of other people who don’t always watch the news closely. My son and I corrected our mistaken first impression, but even first impressions that are proven wrong have a way of lingering, especially, as studies show, if that initial impression confirms something you want to believe anyway.

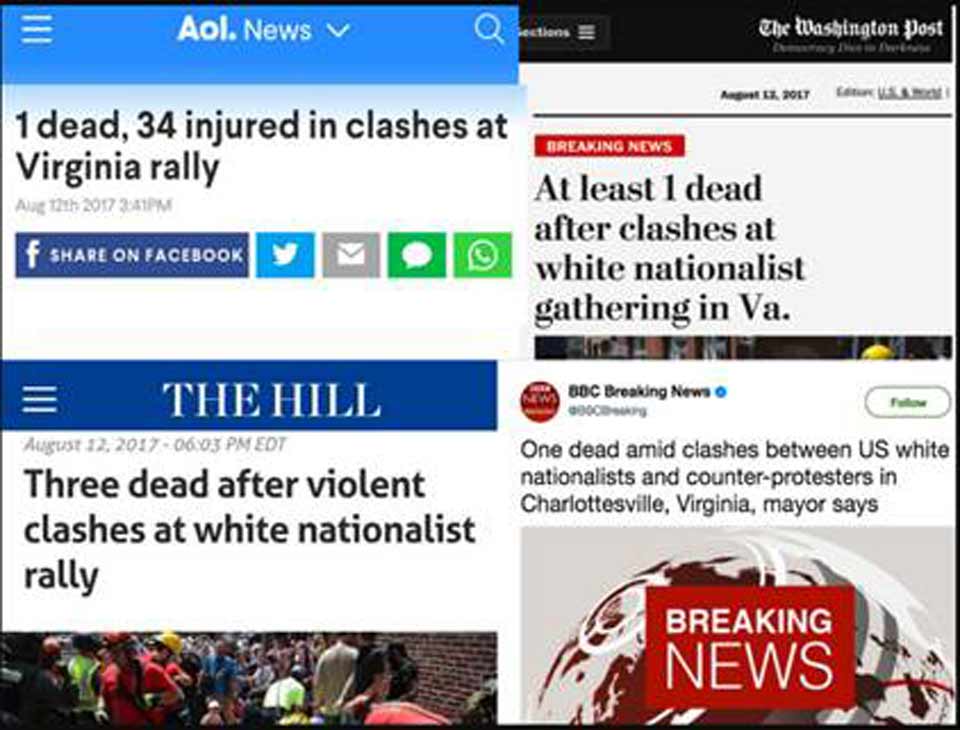

It wasn’t only CNN that produced headlines that invited misinterpretation.“The Washington Post, Boston Globe, AOL News, The Hill, BBC and Sky News UK all chose to frame the ramming of a car into anti-fascist protesters as ‘clashes,’” Adam Johnson writes on the media-watchdog site FAIR.

(Used with the permission of FAIR)

Something’s wrong, Johnson adds, when we’re “attributing agency to an inanimate object and disembodied emotions, as with The New York Times headline, ‘Car Plows Into Crowd as Racial Tensions Boil Over in Virginia.’” (“We have to stop these cars from coming into the country until we can figure out what the hell is going on,” someone tweeted.)

Social media ridicule sent that and other risible headlines about Charlottesville to rehab. The Times changed the hed to the only marginally clearer, “Man Charged After White Nationalist Rally in Charlottesville Ends in Deadly Violence.”

But wait, you might say, weren’t these news sites simply being careful, trying to avoid jumping to conclusions in the hours immediately following the chaos? Well, not really. Even if they weren’t yet ready to identify the driver, the stories and photo captions that they ran under the headlines and behind the chyrons made it perfectly clear that the car mowed down the counter-demonstrators—and not the white nationalists they were demonstrating against.

The Times, for example, both online and on page 1 of the paper, wrote that “a car slammed into a group of counterprotesters after a rally by white nationalists on Saturday in Charlottesville, Va.” A second caption inside the paper said, “19 injured when a car ran over a group of counterprotesters at the end of the rally.”

Making it all a little odder, most of these stories cited criticism of Trump for obscuring who should get blamed in his now infamous “many sides” statement on Saturday.

Why do they do this? I highly doubt that the misleading messages last weekend were deliberate. At best, they were sloppy; at worst, they were the product of a corrosive both-sideism, which is based in part on a fear of facing the wrath of the right. It is possible, however, that after this last week, as Trump fully unleashed the fire and fury of American racism, some of the mainstream press will start to check their knee-jerks toward false equivalency. After all, some of them, notably the Times, have learned that they can write that Trump “lies” and still survive.

Whatever happens in the coming weeks and months, whether right-wing rallies fizzle or conflagrate, it’s worth remembering that all this could yet go the other way: vague headlines and misleading chyrons could one day obscure possible violence from the left. Groups like antifa are far, far less violent than the white nationalists, as Peter Beinart explains in The Atlantic. But if any serious violence sprouts from the left, Trump and Republicans now meekly critical of him would feel justified in resurrecting the “both sides” battle cry. It’s crucial that progressives not react in kind.