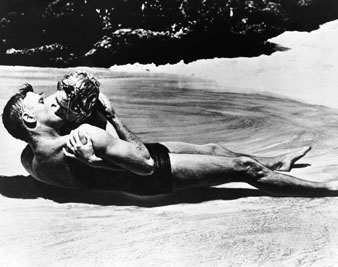

Everett CollectionBurt Lancaster and Deborah Kerr in one of the most iconic screen kisses of all time, 1953.

Everett CollectionBurt Lancaster and Deborah Kerr in one of the most iconic screen kisses of all time, 1953.

Actually, what will be shown from here to eternity will be Burt Lancaster and Deborah Kerr cavorting on the beach.

From Here to Eternity must have seemed like a chore to its director, Fred Zinnemann. He is inspired by experimental films in which the actors are new to movies and the story has an amateurish ring, while this picture is based on a best-selling novel and carries a load of famous “name” players and a budget, $3,000,000, that has to make the final product look slick. It held my interest until the final reel, when the bombing of Pearl Harbor suddenly turned up, but I don’t think its success is due either to Zinnemann, who sentimentalized a lot of James Jones’s story, or to Taradash, whose adaptation moves too quickly through the various love affairs, feuds, drinking bouts.

The laurel wreaths should be handed cut to an actor who isn’t even in the picture, Marlon Brando, and to an unknown person who first decided to use Frank Sinatra and Donna Reed in the unsweetened roles of Maggio, a tough little Italian American soldier, and Lorene, a prostitute at the “New Congress” who dreams of returning to respectability in the states. Sinatra plays the wild drunken Maggio in the manner of an energetic vaudevillian. In certain scenes–doing duty in the mess hail, reacting to some foul piano playing–he shows a marvelous capacity for phrasing plus a calm expression that is almost unique in Hollywood films. Miss Reed may mangle some lines (“you certainly are a funny one”) with her attempts at a flat Midwestern accent, but she is an interesting actress whenever Cameraman Burnett Guffey uses a hard light on her somewhat bitter features. Brando must have been the inspiration for Clift’s ability to make certain key lines (“I can soldier with any man,” or ‘No more’n ordinary right cross”) stick out and seem the most authentic examples of American speech to be heard in films.

The story is supposed to give you tho lowdown on the professional soldier – it is about the thirty-year men in Company G at Schofield Barracks, Honolulu. Taradash juggles a number of plot threads–a clandestine romance between a smart top sergeant and the captain’s sexy wife, the brutal treatment of a new transfer who refuses to box on the company team, the feud between Maggio and a sadistic captain who operates in the “stockade”–in such a concise way that they seem to be bouncing off one another. In one crucial section a love affair on a lonely beach and another in a crowded brothel are wound together like the strands of a rope. The shift from one to the other is somewhat too abrupt, but it is a minor defect in a highly professional job of writing.

What you are supposed to get is a sour, violent, sometimes funny portrait of the character who makes soldiering his business. It was my impression that the performances were often too fancy and the camera work too arty for a convincing study of tough Americans. The “big” performance is turned in as usual by Clift, as Private Prewitt, a character who has every talent (boxing, bugling, soldiering) except an ability to conform to army pattern. He does an ingenious job of acting a plain, slow-thinking individualist, but he is often working with an actor like Lancaster who does everything with a glib, showy, Tarzanism. Then there are Deborah Kerr, a fluent actress who never lets you forget she is acting, and a number of supporting players like Ernest Borgnine, whose sadism has a Broadway glitter.

From Here to Eternity happens to be fourteen- carat entertainment. The main trouble is that it is too entertaining for a film in which love affairs flounder, one sweet guy is beaten to death, and a man of high principles is mistaken for a saboteur and killed on a golf course. When the soldiers get drunk, the scene is treated in a funny, unbelievable way. When Clift blows his bugle, it is done with a hammy intensity that tries to mimic Louie Armstrong at his showiest. When Lancaster and Kerr are being passionate, on the beach, it is done in patterned action that reeks with a phony Hollywood glamour. The result is a gripping movie that often makes you wish its director, Zinnemann, knew as much about American life as he does about the art of telling a story with a camera.