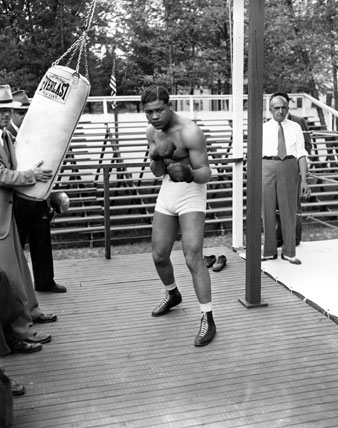

AP ImagesJoe Louis works out with the punching bag in Lakewood, N.J., June 17, 1936, one day before his fight with Max Schmeling.

AP ImagesJoe Louis works out with the punching bag in Lakewood, N.J., June 17, 1936, one day before his fight with Max Schmeling.

James T. Farrell watches as the Brown Bomber becomes the Brown Bombed at the hands of Max Schmeling.

Over forty thousand people were smeared about the Yankee Stadium to witness the predicted murder of the century. Half-interested, they watched preliminary boxers maul for pork-chop money, and they booed when one decision went to an overgrown Argentine battler. Those in the ringside section glanced around to see and to be seen. Photographers swarmed about, the bulbs attached to their cameras flashing like a miniature electric storm. When asked by cops whom they were shooting they tossed off names from Jack Dempsey down. One policeman remarked that the fight wouldn’t last long, that he ought to be getting home early. Everybody waited to see Joe Louis, the “Human Python,” slug Max Schmeling into a coma.

Both fighters received loud ovations when they entered the ring. They sat in their corners while celebrities were introduced. Champions past and present lightly leaped over the ropes, shook hands all around, and took their bows. Jack Dempsey received a bigger hand than Gene Tunney, whom the announcer characterized as “an inspiration to the youth of America.” Mickey Walker, along with others, was revealed as a “thrill-producer.” This formality settled, the fighters were presented, and the announcer exhorted everybody “to cast aside all prejudice regarding race, creed, or color.” I suspected a note of patronage in the responding wahoo.

The crowd waited, keen, alert eyes riveted on the greenroped ring. Nervous conversation popped on all sides like firecrackers. On all sides, too, people were asking each other how long before they would see Schmeling, the “dark Uhlan,” stretched out .The ring was cleared. Handlers whispered final words to the fighters The gong! A loud cheer!

Dark-skinned Joe Louis danced and pranced cautiously about the ring facing a man who seemed clumsy. Louis, feinting with the snap of a trained, perfectly coordinated boxer, seemed to possess an almost insolent confidence. He maneuvered to let go with that deadly one-two punch, a left to the body, and a murderous right cross to the jaw, which was calculated to sink Schmeling quickly into a state of retching if temporary paralysis.

“Fight, you bums!” someone yelled from the grandstand behind me

They sparred and shifted in a first round which went to Louis by a harmless margin. The crowd seemed to be with Schmeling. It coached him, loudly yelling advice and confidential instructions: “Get in there, Max! Bob and weave! That’s right! Don’t stand up straight! Duck his left, Maxie!”

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Near me, there was a thin, cynical-faced chap in a checked grey suit. Peering through binoculars he made himself an unofficial broadcaster for a large area of ringside seats.

“Don’t be a bum, Maxie! You’re yellow, Max! Fighting the kind of a fight Joe wants you to! Down, there! Bob and weave, bob and weave! … Jesus Christ, look at him, standing up straight! Bob and weave! Use that right! Bob and weave!”

Others joined in. “Fight, you Dutch bum!” “Get going, Maxie!””Make it fast, Louis!” Negroes sprayed through the ringside section and the grandstand shouted, some with hysterical confidence. A frail Negro lad wearing brown trousers and a checked gray coat, kept telling Louis, in a mild voice, to hit him. The second round was cautiously fough.t Louis boxed, poised and graceful. Swaying and weaving, Schmeling still seemed clumsy, a man with no right to be in the ring with this black giant.

“He’s feeling the Uhlan out. He’ll tear in in a round or two.”

“He’s giving us a run for our money!”

The gong. The lights going on all over the arena. The high-pitched conversation. The seconds expertly working over the men. Again the gong. All lights off except those over the ring. Matches flashing on all sides as cigarettes were lit in the darkness. A loud and long Oh, and everyone leaping up. Schmeling had bounced Louis back with a powerful right.

“Oh, what a bum! He’s yellow, Max! Get in there, Max! Polish him off! Dempsey would have killed him!” the gray-suited fellow with the binoculars yelled.

“Retaliate, Louis, retaliate!” the frail Negro, with the gray-checked coat called out. His voice was lost in the shrieks for a knockout.

The fellow with the opera glasses kept yelling that Louis was mad and swinging wild now. Louis was no longer the graceful, panther-like animal prancing around in sure expectation of a kill. The fourth round came up. The crowd yelled for blood. Many were asking about Schmeling’s eye, which Louis had nicked in the early rounds. Louis went down. He was up immediately, punching wildly. He swung low with his left, landed. He was booed loudly and nastily.

“Hey Hey! Watch it! Watch it, you!” the fellow with the opera glasses shrieked threateningly.

“Kill him, Maxl” a woman cried hysterically from the grandstand.

Now the crowd cheered and exhorted Schmeling. Shaken by surprise at the unexpected turn of the fight, it wanted blood. Here and there Negroes began showing concern. Some were silent; others pleaded with Joe to win. The frail lad with the gray-checked coat meekly begged Louis to retaliate, his words drowned out by successive roars.

And the heart seemed utterly gone out of Joe Louis. Hurt, he floundered. Missing punches, he revealed the manner in which the German’s plan of battle was working effectively. Drawing Louis to lead with his left, Schmeling ducked under the Negro, and pegged in solid right-hand smashes. Now many yelled that Louis couldn’t take it. After each gong he wobbled about, scarcely able to find his own corner. Loud and gleeful voices announced that the black boy was out on his feet. The superman of pugilism had been turned into a “bum” by one knockdown and a pounding succession of drives from Schmeling’s right hand.

Groggy for two rounds, Louis seemed to recover in the seventh round. He attacked and the mob was on its feet, ready to shift its allegiance as he banged at Schmeling.

“He ain’t hittin’ Max! He’s hittin’ Maxie’s gloves! Louis’s face is hamboiger! It’s hamboiger! He’s a sucker for a poifict right! Go in with the right, Maxte, and you’ll kill the yellow bum!” the smart Aleck with the binoculars crowed.

“Retaliate, Louis, retaliate!”

For eight rounds Schmeling punched Joe Louis into a state of bewildered, rubbery-legged semi-helplessness. Louis swung wildly, feebly. Before the end Schmeling was laughing at him. The German continued to light cautiously, ploddingly, slugging away until he grew armweary. A few called to the referee to stop it. One fellow began yelling that Schmeling was a bum because he was taking so much time to knock out a thoroughly beaten man.

The roaring grew in volume. From behind, there came petulant repetitive cries for those in front to sit down. Schmeling was exhorted to polish Louis off; to kill him. Louis, utterly confused and swinging aimlessly, landed several low punches. He was booed. Then finally Schmeling straightened Louis up and bounced a last needless right off his face. Louis fell into the ropes, relaxed, slid on to the canvas, quivered, turned over. A long and lusty roar acclaimed the end of one superman and the elevation of another superman to supplant him in the sports columns.

The beaten heavyweight was led off, half dragged,half carried, his face smothered in a towel. A last pitying but friendly cheer followed him. Schmeling departed, guarded by an aisle of policemen, waving and grinning at the plaudits which acknowledged him the hero of the evening.

In the dressing-room Schmeling stood under a spraying shower, surrounded by reporters, his dark hair sopped, answering questions with a heavy German accent. His middle covered with a towel, he crushed his way out of the shower to dress. Photographers clambered on chairs, and flashed his picture continuously. Reporters asked the whiner how he had won, and solemnly copied his statements down on note paper. He said that Louis was a good boxer, but could be hit, and that Louis’s punches had not hurt him seriously, except for the low ones.

“Hey, Max, please smile! I want you smiling and I’m finished,” one of the photographers pleaded.

Again Schmeling was asked how he won, and his answers were noted. The experts described the statements as fine and excellent. He spoke of the “shampionship.” He was congratulated tumultuously on all sides. His manager, a corpulent, slack-faced little man, was chewing a cigar, wiping oceans of perspiration from his brows, and chiding the experts who had picked Louis. A sweating radio announcer with a handkerchief strung around his neck was concluding his broadcast in a thick, insinuating, histrionic voice.

“Hey, Maxie, please smile! Hey, tell him to smile! I can’t go home till I get a shot of him smiling. Hey, Max, smile for just a second!”

Schmeling was dressed now, gay, not worrying over his bruised eyes. He has dark hair, heavy brows, a long, bony face. He is an ox-like, genial, stupid-looking German, his features from some angles almost suggestively animalistic.

“Hey, please, get Max to smile. For Christ sake, I can’t go home until I get him smiling!”

A few minutes later Schmeling broadcast a statement to Germany, where the Nazis will make political capital of the fight and claim that Max Schmeling’s victory is a triumph for Hitler and Wotan.

Dressed in a loud gray suit, with a straw hat askew on his enormous head, Joe Louis sat bowed. The son of exploited Alabama cotton pickers, he had in two years earned around a million dollars in his so-called “meteoric” rise in the prize ring; he had just earned well over one hundred thousand dollars. Now he sat like a sickened animal. He is a large Negro boy with blown-out cheeks, fat lips, and an overdeveloped neck. His face was puffed and sore. He dabbed his eyes with a handkerchief, revealing bruised knuckles. His trainer bent down and whispered to him, calling him Chappie. A second massaged his neck. He sat dazed, stupefied from punishment. Again he dabbed his eyes. A Negro boxer who had won a preliminary bout on a technical knockout dressed in an outer room, explained how he had gone into the fight to win; he entered Louis’s quarters, talked condolingly with him, departed. Photographers stood on chairs, awaiting Louis’s exit, begging for just one picture. Loud cheers echoing from outside heralded Schmeling’s departure. Louis sat, still punch drunk. He went out like a drunken man, surrounded by cops and members of his retinue, his face hidden behind a straw hat and the collar of his gray topcoat. Unsupported, he would have fallen. The helpless giant was pushed into a taxicab and hustled away while a crowd fought with the police to obtain a glance at him.