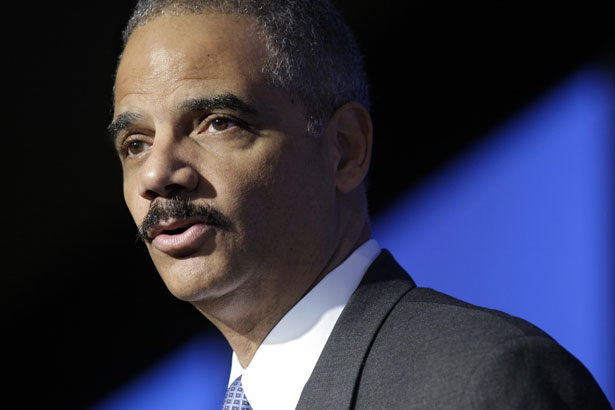

Attorney General Eric Holder.(AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

On Monday, August 12, the day Attorney General Eric Holder announced “a fundamentally new approach” to the criminal justice system in his speech before the American Bar Association in San Francisco, US District Court Judge Mark W. Bennett was in his office in Sioux City, Iowa, drafting a sentencing opinion in a drug case. An outspoken critic of mandatory minimums [see “Imposing Injustice,” November 12, 2012], Bennett is known for writing unusual opinions that criticize the sentences he must often hand down. “It’s about trying to make the system fairer,” he says, “not just for the defendant in front of you, but for others.”

The defendant in this case, a 37-year-old black man named Douglas Young, had caught a rare break. He’d pleaded guilty to two charges involving twenty-eight grams of crack cocaine—an amount sufficient to trigger two five-year mandatory minimum sentences. But he had previously been convicted on another crack charge, in Chicago, when he was just 20 years old. This single offense, seventeen years ago, meant not only that prosecutors could have doubled Young’s mandatory minimum sentence, but also that he could have received a maximum sentence of life without parole.

Thanks in part to a good defense attorney, who successfully argued that this single drug conviction did not constitute a criminal past, Young won’t spend his life in prison. Nonetheless, Judge Bennett wrote, “this case presents a deeply disturbing, yet often replayed, shocking, dirty little secret of federal sentencing: the stunningly arbitrary application by the Department of Justice (DOJ) of § 851 drug sentencing enhancements.” Such extra punishments—also known as ”recidivist enhancements,” and often used to scare a defendant into pleading guilty—“at a minimum, double a drug defendant’s mandatory minimum sentence,” Bennett wrote. They “are possible any time a drug defendant, facing a mandatory minimum sentence in federal court, has a prior qualifying drug conviction…o matter how old that conviction is.”

Holder did not mention sentencing enhancements in his August 12 speech. But in a Justice Department memo issued that same day, which instructed federal prosecutors to avoid mandatory minimums, the attorney general recommended that they also stop applying recidivist enhancements, “unless the defendant is involved in conduct that makes the case appropriate for severe sanctions,” such as a history of violence or leading a “criminal organization.”

Decades have passed since Congress created such “tough on crime” enhancements as part of Nixon’s “war on drugs,” yet this was the first time Justice had bothered to specify, in any detail, how they should be used. Although Bennett thinks Holder’s criteria for using sentencing enhancements are still too broad—“You could drive an armored truck through any one of them,” he says—they’re at least a step in the right direction, given the arbitrariness of their earlier use. As he wrote in his sentencing opinion in Young’s case: “I have never been able to discern a pattern or policy of when or why a defendant receives a § 851 enhancement in my nearly 20 years as a U.S. district court judge who has sentenced over 3,500 defendants, mostly on drug charges.”

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

To grasp the consequences of such a lack of policy, Bennett sought out whatever data existed. A 2011 study by the US Sentencing Commission had found “a lack of uniformity” in the application of sentencing enhancements, so Bennett requested the raw data in order to delve deeper into the disparities. What he found when he crunched the numbers was “jaw-dropping,” he wrote. The commission’s conclusion had been a “gross understatement.” Bennett’s final seventy-five-page opinion, complete with charts and graphs, is not just a scathing critique of harsh and nonsensical punishments; it also starkly illustrates the challenges that the Justice Department confronts if it is truly sincere about reining in unfair drug sentences.

“For unknown and unknowable reasons,” Bennett wrote, “federal prosecutors have been applying massive numbers of § 851 enhancements in many districts and not in others.” In his own Northern District of Iowa, where 79 percent of eligible defendants get such added punishment, a drug offender is “2,532% more likely to receive it than a similarly eligible defendant in the bordering District of Nebraska.” (Many of these defendants, he added, are arrested on drug conspiracies and could actually be charged in Nebraska.) The arbitrariness is striking within states as well: in Tennessee’s Eastern District, “offenders are 3,994% more likely to receive a § 851 enhancement” than in the Western District. In other words, based on geography alone, some defendants will spend decades longer in prison than others for virtually identical drug crimes. Bennett likened it to a “Wheel of Misfortune” that has been allowed to spin unchecked for decades. “It has added thousands of years of arbitrarily inflicted incarceration on drug defendants, most of whom are non-violent drug addicts,” he wrote.

Of course, in many ways, such disparities fit into the wider landscape of unfair punishment that Holder invoked in his speech. The use of mandatory minimums, enhanced or otherwise, have so disproportionately devastated communities of color that real fairness would require abolishing them entirely. But given that such harsh punishments for drug crimes have been kept in place, would the Justice Department’s new guidelines actually make them fairer? That will depend, ultimately, on whether federal prosecutors decide to follow them. After all, as Bennett wrote, the Wheel of Misfortune is spun by “more than 4,500 Assistant U.S. Attorneys nationwide.”

For former federal prosecutors like Mark Osler, a law professor at the University of St. Thomas in Minneapolis, this cuts to the heart of the problem. In an editorial bluntly titled “Why Eric Holder’s drug policy changes won’t work,” Osler dismissed as “myth” the notion that a directive from Washington would have a sweeping impact on drug sentencing. “The truth is that federal prosecutors who want to charge harshly will find a way to do so,” Osler wrote. (He also noted, “prosecutors everywhere use mandatory minimums to pressure low-level defendants to flip and provide information on others, and that is unlikely to change.”)

Indeed, for any number of other reasons—from a particularly punitive sense of justice to crass professional gain—prosecutors routinely use all kinds of enhancements to lengthen sentences, and neither judges nor Holder’s recommendations have much power to interfere. The advocacy group Families Against Mandatory Minimums, which maintains prisoner profiles on its website, offers example after shocking example of what this can mean in human terms. “This man doesn’t deserve a life sentence, and there is no way that I can legally keep from giving it to him,” one judge wrote in the case of a nonviolent drug offender.

Angela J. Davis, author of Arbitrary Justice: The Power of the American Prosecutor, points to another problem: lack of transparency. “Charging and plea bargaining decisions are made behind closed doors, and prosecutors are not required to justify or explain these decisions to anyone,” she wrote in The New York Times earlier this year. Bennett argues that this “incredible cloak of secrecy” must be lifted if Holder’s memo is to mean anything. “It’s really going to depend on the amount of scrutiny given to those on the front line.”

In the midst of an ongoing “war on drugs,” however, those on the front line will always have an incentive to send people to prison who don’t belong there—and any fundamental rethinking of our criminal justice system would require Congress, not merely the Justice Department, to admit this. In the meantime, there is a tool at the administration’s disposal that, as Osler pointed out, could have a sweeping and immediate impact: “The pardon power. The president can, and should, shorten the sentences of those who have been oversentenced for drug crimes.”

After all, if the Obama administration truly believes that “too many Americans go to too many prisons for far too long,” isn’t this the logical place to start?

In August, Democratic Congressman Steve Cohen of Tennessee asked President Obama to commute the sentences of low-level drug offenders.