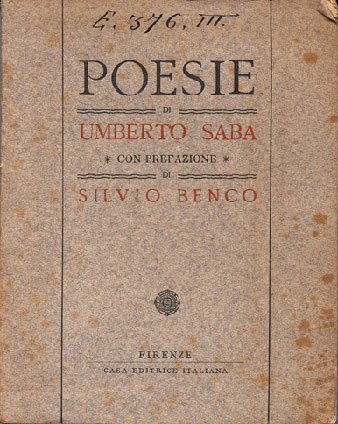

DUKE UNIVERSITY LIBRARIESCover of a first edition of Umberto Saba’s Poesie, 1911

DUKE UNIVERSITY LIBRARIESCover of a first edition of Umberto Saba’s Poesie, 1911

“Everything in Trieste is double and triple, beginning with its flora and ending with its ethnicity,” proclaimed the Triestine writer Scipio Slataper in an essay from 1911 on “Irredentismo,” the desire of the inhabitants of Trieste and other hinterlands of the Austro-Hungarian Empire to be united with the Italian mainland, and hence “redeemed.” Tucked below the barren limestone promontory called the Carso by Italians, the Karst by Austrians and the Krš by Slovenians, and pummeled by the local northeast wind, the bora, Trieste has become most renowned since the early twentieth century for its shape-shifting pseudonymous writers: the poet/memoirist Slataper, killed at 27 fighting for the Italian cause in World War I, who wrote as Pennadoro, an Italian translation of his Slavic surname; the novelist Ettore Schmitz, friend and student of James Joyce, who set out with the pen name E. Samigli before christening himself Italo Svevo; and one of the most important poets of Italian Modernism, Umberto Poli, who used the signatures Umberto Chopin Poli, Umberto da Montereale and Umberto Lopi before settling in his late twenties on Umberto Saba, the name we know him by today.

The author of more than fifteen individual books of poetry and a thousand pages of prose, Saba is best known for his Il Canzoniere (The Songbook), a continually revised and augmented collection in poems of his life’s work. Like Ezra Pound, another Modernist who liked to travel forward while facing backward, Saba chose this simple title to claim his place in the long line of great Mediterranean poets who had used it for their collections, including Guido Cavalcanti, Francesco Petrarca and Giacomo Leopardi. This new volume of selections from Saba’s Songbook, edited and translated by George Hochfield and the late Leonard Nathan, has been handsomely produced by Yale University Press; not among the least of its attractions is how well it fits in the hand. The edition includes, among other work, a generous number of Saba’s earliest poems; all fifteen sonnets of his important Autobiografia (1924); several of his experimental works of 1928-29, titled Preludes and Fugues; and a sampling of his late-life poems, including his beautiful sequence Uccelli (Birds) from 1948. Hochfield and Nathan also provide a translation of Saba’s early essay, published posthumously, “What Remains for Poets to Do”–an ars poetica clarifying his search for a poetry of sincerity and a rejection of rhetoric.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Clearly a labor of love, these collaborative versions, presented with the Italian on facing pages, occupied Hochfield and Nathan for more than a decade. Inevitably they will be compared favorably to Stephen Sartarelli’s translations from the Canzoniere, which were published in 1998 by Sheep Meadow Press alongside Sartarelli’s version of Saba’s massive prose account of his poems, Storia e cronistoria del canzoniere (History and Chronicle of the Songbook). Sartarelli’s pioneering efforts remain admirable, and it is certainly not the case, as the book jacket of the Hochfield and Nathan edition touts, that “until now…English-language readers have had access to only a few examples of this poet’s work.” The two Sartarelli volumes total nearly 500 pages of translations and in fact are listed in Hochfield and Nathan’s bibliography, although Vincent Moleta’s expansive 2004 Australian translation of Saba’s prose and poetry goes unmentioned. Even so, Saba’s final edition of Il Canzoniere alone runs to more than 600 pages, with another 330 pages of Canzoniere apocrifo; each of these translations, therefore, must be presented as “selected poems,” and our understanding of Saba, despite his fame, remains at an early phase.

Umberto Poli was born in Trieste in 1883, when the city was at its zenith as the major port of the Habsburgs. The irredentist sympathies of Umberto’s Italian-speaking parents can be detected in their giving him the first name of the Italian emperor. His mother, Felicita Coen, was Jewish and his father, the widower Ugo Edoardo Poli, was not, although he did convert to Judaism at the time of the wedding, taking the middle name Abramo and undergoing circumcision. Within months of the marriage, however, Ugo abandoned his new family, and the baby was sent for his first three years to a young Slovenian wet nurse, Gioseffa Schobar, or Sabar, nicknamed Peppa–the pseudonym Saba is perhaps derived from the surname of this beloved muse. Umberto would meet his father only once, an encounter he describes, with his characteristic emotional ambivalence, in his poetic Autobiografia: “My father had been ‘the assassin’ to me/until I was twenty, when I met him./I saw right off that he was a child,/and the gift I have I had from him.”

Shifted between female relatives in infancy, and an only child, Saba spent most of his school years in Trieste, where he was an indifferent student. Nevertheless he was drawn to the poetry of Leopardi, and in his late teens he began to write poems and learned to play the violin, joining a circle of musicians, painters, writers and socialist journalists around the magazine The Worker. A brief period attending the University of Pisa resulted in a nervous breakdown, the first of many attacks of “neurasthenia,” and he returned to Trieste to recover. During the ensuing years, Saba often traveled to Florence, mixing in irredentist literary circles there and adopting a Tuscan accent that he used whenever he read aloud from his poetry. In retrospect, his recurring nervous breakdowns seem rooted from the start in the separations of his childhood and the complexities of his identity: a Jewish subject of the Habsburgs by birth, a Roman Catholic Slovene by nurture, an Italian by virtue of his absent father’s Venetian origins and a bisexual made anomalous by a heterosexual society. He wrote in an early Leopardian poem to his mother: “…I think/my cradle was cut from a different wood./My spirit always yearned for a sign/that my gentle friends did not yearn for.”

Poli’s service with the Italian army in 1907 led him to write a new and intense kind of lyric, his “Military Verses.” Often relying on the nocturne form, he developed in these poems a view from below that would later shape his many genre scenes of Trieste in peacetime. He describes his fellow soldiers on maneuvers and at rest, crawling on the ground, snoring, exhausted in their cots. His humane sympathy extends to a view of the earth as animals might see it: “the animals, for whom it’s home, and bed,/and bridal chamber, and farm, and table, and everything.”

Two years later, he married Carolina (“Lina”) Wölfler, and within a year his daughter Linuccia was born. Professing “Trieste è la città/la donna è Lina,” Saba addressed his native city and his marriage with equal measures of tenderness and realism. His well-known tribute “To My Wife” compares his bride to a young white hen, a frisky pregnant heifer, a slender dog, a timid rabbit, a faithful swallow and a thrifty ant, finding her in “the females of all/the peaceful animals/that are near to God./…and in no other woman.” The marriage was troubled and combative from the beginning, and Saba wrote unflinchingly of his feelings about their many mutual betrayals; but the tie endured until the two died within months of each other in 1956-57.

Saba’s poetry is replete with erotic fantasies–perhaps erotic narratives, it’s hard to tell–regarding young boys and girls. His attraction to boys was bound up with the strain of Italian poetry nourished by the work of Giovanni Pascoli, who elaborated a concept of the poet as fanciullino (little boy), a figure who maintains his childish sense of naïveté and wonder. Many of Saba’s poems describe boys playing sports, running about the streets of Trieste or wandering amid boats on the shore and along the beach. Repeatedly, Saba notes his identification with them: “He has something of me from the distant/past,” he writes in “The Boy Enthralled”; “Guido has something of my spirit,” he notes in his pastoral poem “Guido.” Saba’s series Little Berto (1929-31), dedicated to his psychoanalyst Edoardo Weiss, returns to the house of Peppa and the theme of infancy as the root of adult conflicts. His guardian angel, he believed, was “a little boy larger than I, but not by much,” who wore “light blue knickers” and “carried a white feather.” These projections and identifications, however much they involve the Telemachus scenario of a boy searching for a missing father, also indicate the same-sex attraction described in Saba’s posthumously published unfinished novel, Ernesto. Meanwhile, he would often sign his letters “Ernesto,” although within the letters referring to himself as Saba.

Fanciulle (Girls) is the title of a collection published in 1925, and here, too, affection and erotic attraction are often confused, troubled and troubling. His “Paolina,” “Chiaretta,” “Fiammetta,” “Erna,” appeal to him because they are not yet women: “I don’t believe in woman. I mean/no insult when I say that,/if man has an enemy,/it is always woman…” The misogynistic theories promulgated by the Viennese philosopher Otto Weininger in Sex and Character (1903), which were a vogue of the Middle European (male) intelligentsia at the time, cast their shadow on this work. For better or worse, Weininger, Nietzsche and Freud became, as they were for so many of his peers, the intellectual pillars of Saba’s thinking. Without their iconoclastic approaches to emotion and self-knowledge, Saba may never have become the “honest poet” he extolled in 1911 in “What Remains for Poets to Do.”

After brief service in the military administration during World War I, and a consequent period of treatment in a military hospital for another episode of neurasthenia, Saba returned to a newly Italian Trieste. He opened a bookshop with a typically ecumenical name–the Libreria Antica e Moderna–on the Via San Nicolò. Saba called the shop “this living memorial to the dead,” and he published much of his work under its imprint, including, in 1921, the first-edition Il Canzoniere. Before his death, four more editions, continually refashioned, would appear. The Libreria is managed today as a kind of museum of Sabiana by Mario Cerne, the son of Saba’s assistant Carlo Cerne, to whom he entrusted the shop during the worst of the persecutions of the Second World War.

Trieste had long been a port of embarkation for Palestine, with European emigration reaching its peak in 1935, yet most of the local Jewish population stayed in the city; and by 1938, as Fascist racial laws came into effect and the British closed down immigration, they were trapped. Then, in September 1943, the Italians signed an armistice with the Allied powers, and the Nazis took over Trieste within a day, setting up an extermination camp in a former rice treatment plant at the edge of the city. Saba and his family fled to Florence. They were hidden in eleven different houses there during the remainder of the war and never reported. Eugenio Montale, also hiding in Florence, visited them, despite the danger, every day.

At war’s end, his beloved Trieste a no man’s land ruled jointly by Allied forces from 1947 until 1954, when it was again annexed to Italy, Saba lived first in Rome, then in Milan. Although his work began to win some of the most important national poetry prizes and he was given an honorary degree by the University of Rome, his health declined and he became addicted to opium. Between 1954 and 1957 he worked without closure on Ernesto. His final years were despairing. Lina died in the late winter of 1956, and he died the following summer.

Any edition of the Songbook will compel the reader to turn to Saba’s most famous poem, “The Goat,” which first appeared in House and Countryside (1909-10). Here is the Hochfield and Nathan version:

I talked to a goat.

She was alone in a pasture, and tethered.

Stuffed with grass, soaked

by the rain, she bleated.

That monotonous bleating was brother

to my sorrow. And I answered, first

in jest, then because sorrow is eternal,

has one voice and never changes.

I heard this voice in the wails

of a solitary goat.

In a goat with a Semitic face,

I heard all other pain lamenting,

all other lives.

Much of Saba’s poetic destiny is already written into this brief lyric. The first-person voice is not directed toward expression but rather toward the empathy of imaginative listening. For although we cannot know the pain of any other living being, the specificity of the pain of the crying animal is particularly opaque to us. Saba emphasizes this by first letting us know that this solitary goat is not hungry; she seems to suffer from the rain alone, to be the very manifestation of a wail that precedes and follows her and that we human beings, too, might embody. It is not the goat that is “fraterno al mio dolore” but the bleating itself. In the Italian, Saba is able to make this shift from the particular to the general via a switch in tense: “Ho parlato a una capra” (“I talked to a goat”) is in the passato prossimo, indicating an action completed in the recent past; “belava” (“she bleated”) is in the imperfect, indicating a longstanding or frequently repeated action in the past. The incommensurability between what the poet was able to say to the goat and the eternal sorrow of its “uguale” bleating is thereby emphasized; similarly in this goat with a “Semitic” face, a face of ancient traditions of lament that were Saba’s birthright, he recognizes a mirror image that is as well not a mirror image.

The poem provoked a number of anti-Semitic responses from established critics: the young Slataper, ever self-promoting, criticized Saba as living “in uncertain nostalgic memories”; “non è classico italiano,” another critic wrote of Saba’s deeply classical work. Years later, in his Storia, Saba responded to these comments, writing that the “memory of his maternal blood line” informed many of his poems, but that “a goat with a Semitic face” was “predominately visual…it is merely a thumbstroke applied to the clay in shaping a figure.” The goat’s suffering has something to do thereby with its solitude and a too-ready stereotyping of its appearance. The Italian word ogni in the last lines–“ogni altro male, ogni altra vita“–is deftly able to express this, for the word can indicate at once “every,” “each,” or “all.” Hochfield and Nathan have gone the sweeping route of “all other pain” and “all other lives,” but the singular forms of “male” and “vita” at the end of the poem would lend equal value to “each other pain, each other life.”

Placing Saba involves recognizing that the adherents of international modernism in poetry, cutting their ties to the meters, rhymes, narratives and voices of the past, were most often preoccupied with visual form and mechanical motion. Yet for Italian lyric poets, abandoning traditional sung and spoken forms was never an easy matter. Filippo Marinetti had called Trieste, in a 1909 speech, “our beautiful powder-magazine,” and the city became the site of the first Futurist “serata” at the turn of 1910. Saba, however, just a year later defined himself in exact opposition not only to Futurist rhetoric but also to the longer declamatory poetic tradition of Giosuè Carducci and Gabriele d’Annunzio. Saba insisted he was a “cobbler” who wanted to resole old forms and ground them in “our earthly existence.” His poems bear no record of the innovations of twentieth-century technology–no celebrations of airplanes, trains or radios. He saunters through every street of Trieste, catching glimpses of the city’s manifold forms of life; his sky holds a little cloud that has haunted him from childhood; his real blackbirds eat real pignoli. Saba bears a loving skepticism toward the world that speaks to his long familiarity with the poems of Heinrich Heine. And it was Heine, his own books destined after more than a century to be burned by the Nazis, who knew that “where they burn books, they will eventually also burn people.” In an era of noise and terror, Saba relied on poetry as a refuge of quiet conscience, describing how, during the Fascist years, he hid “more than ever within himself, plugging his ears–even literally–so as not to hear the voices of the loudspeakers.”

The remarkably stable pacing of Italian syllables gives any Italian line a certain crisp exactitude; and the remarkably stable pronunciation of Italian vowels makes any ordinary sentence in Italian chime like a set of sleigh bells. Each member of the great triumvirate of Italian Modernist poets,Giuseppe Ungaretti, Montale and Saba, therefore, had to find a way to forge a Modernist poem under these essential features of the language and the great light that Italian lyric cast on all Western poetry. Ungaretti turned to minimalism, refining the language to its essence, honing his work to the mystery inherent in arrangements of crystalline words. Montale usually rhymed without pattern, breaking his lines before or after the expected hendecasyllabic measure and, above all, relying on image and irony. Saba, however, took a different path, drawing so deeply on rhyme and the lyric tradition, adapting them in such surprising ways to present circumstances, that tradition seemed to speak to and through modernity. He wrote, “I loved the worn words that no one else/dared use. I was enchanted by the rhyme fiore/amore,” concluding, “I loved the truth that lies in the depths,/almost a forgotten dream, that pain/rediscovers as a friend.” Using archaisms and local terms, taking up Dante’s Tuscan accent, he addressed the humblest, most overlooked figures of Trieste–the city’s servants, children, prostitutes, sailors and factory workers.

Yet the strongest formal influence upon these poems of relentless psychological honesty is Petrarch: his hendecasyllabic line, variations in sonnet and canzone form and use of refrain. A note in the 1913 diary of Saba’s friend Aldo Fortuna gives us some sense of Saba’s ease with Petrarch’s meter. Fortuna records how, waiting for a doctor’s visit one day, he proposed a waiter’s litany to Saba as a “typical hendecasyllable for an Italian poem”: “Venerdi baccalà, sabato trippa” (Thursday salt cod, Saturday tripe), and in a flash Saba came back with a rhyming hendecasyllabic response for dessert: “Mezza granita di caffè con panna.” Coffee “shave ice” (as the Obama family calls it) with whipped cream.

Saba’s poetry is autobiographical under conditions where having a life and the means to record it could not be taken for granted. Yet his work was not in consequence absorbed by its historical moment; his protégé Sandro Penna, who died in 1977, was his most direct heir, both in clarity of style and in homoerotic, often pederastic themes. Saba’s straightforward language, use of traditional forms and realism also have had an impact on the work of many of the leading Italian poets today, including poems of everyday emotion by Valerio Magrelli, Patrizia Cavalli, Milo De Angelis and Antonella Anedda, and the intricately rhyming patterns of Patrizia Valduga. We can be grateful that Saba failed to fulfill the prediction of his “For a New Fable” (1947-48): “Every year a step forward and the world ten/steps back. In the end I have remained alone.”