Daniel joined the line of people and followed the smugglers under cover of darkness to the sea. In the humid evening, he waited to board a boat docked off the coast of Libya. Over the past six years, he had slept in a refugee camp in Ethiopia, in an Israeli prison, in the sand and dirt of the Sahara desert. Tonight, he would not sleep.

Daniel was in the final stage of a seemingly impossible quest to reach Europe. After fleeing a brutal dictatorship in Eritrea, he’d sought safety and freedom from East Africa to the Middle East. (The names of the people in this story have been changed because they still have family in Eritrea.) At every stop along the way, the world’s response to the crisis of displacement failed him. Like the 343,000 other refugees and migrants who arrived in Italy and Greece via the Mediterranean last year, his story illuminates a system so broken that people risk their lives to escape it. These are the people against whom President Donald Trump barred the doors of the United States last week, and whom European nations have refused to welcome for years.

Daniel never imagined that he would become one of the 65.3 million displaced people worldwide. He was born in 1984 in Shire, Ethiopia, one of seven children. But his parents were Eritrean, and when Daniel was around 10, the family returned home. Eritrea had just gained its independence from Ethiopia, following a 30-year war between the two countries. Violence would continue to erupt over the next decade, but 1993 was a time of optimism in Eritrea. The country’s newly elected president, Isaias Afwerki, had led the military struggle for independence, and his ascension seemed to herald a brighter future.

In fact, from his new seat of power, Afwerki was slowly constructing one of the world’s most repressive dictatorships. Daniel, sheltered as a child by his large extended family and rural surroundings, first woke to the encroaching reality of Afwerki’s cruelty when he was 13 and his older brother, Tewelde, fell ill with liver complications. Tewelde, who had worked for the government for five years, was unable to get treatment in Eritrea, but a German friend offered to sponsor his care abroad. The Eritrean government denied Tewelde an exit visa; he died a few months later. “To see someone dying in front of you is the hardest thing in life,” Daniel says.

The same year as Tewelde’s death—1997—Afwerki refused to hold the scheduled national elections; as of 2016, no election has ever been held in the country. Afwerki also made military service compulsory: Everyone under the age of 50 is enlisted for an indefinite period of time and subject to manual labor, constructing roads and buildings.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Daniel was 19 when he began his mandatory service, stationed at the notorious Sawa military base. Within two weeks, he developed chronic diarrhea from the harsh conditions; he dropped from 140 pounds to less than 100 in a matter of weeks. Meanwhile, his defiant temperament constantly drew the officers’ anger. As punishment, he was ordered to crawl on the ground under the hot sun for hours until his elbows bled and he lost feeling in his arms.

Daniel thought about running away, but Afwerki had a web of informants across the country to catch deserters. Those who tried to end their military service early were brought back and executed in front of the other soldiers. At Sawa, Daniel saw two young escapees shot to death. The worst part of his service was that you never knew if or when you’d be released; it meant living in an indefinite hell. After five years, the military moved Daniel from active duty to a military college, complete with its own jail for students who questioned its teachings or the regime.

Daniel wanted to study mechanical engineering, but he could no longer imagine a future in Eritrea where he wasn’t in prison or dead. In May 2008, at the age of 24, he decided to join the multitudes of young people who were escaping across the border to Ethiopia. Hundreds of thousands have left Eritrea over the past decade; today, some 5,000 people leave the country every month.

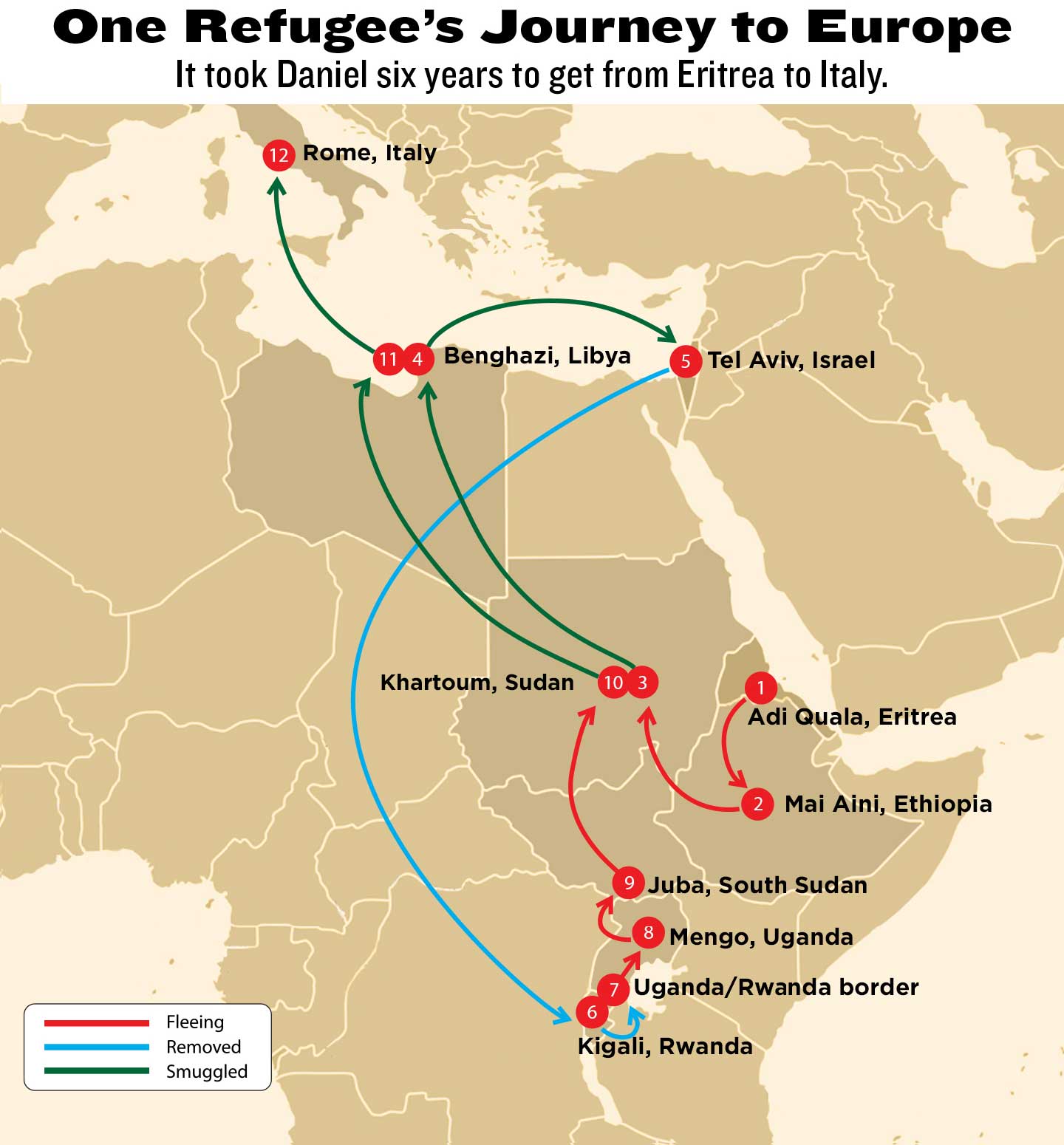

So Daniel followed in the footsteps of his next-door neighbor and new girlfriend, Kedijah, who’d recently headed for Ethiopia. He didn’t tell his parents he was leaving. He traveled after sundown with a friend, from the town of Adi Quala south toward the Ethiopian border, carefully avoiding any official checkpoints, where armed guards have a shoot-to-kill policy. They walked most of the night, crossing a river and a stretch of wilderness, and then Daniel was back near his birthplace—this time as a refugee.

A refugee is most commonly defined as “someone who has been forced to flee his or her country because of persecution, war, or violence.” Meeting that definition—as Daniel did—entitles you to certain forms of protection and aid: primarily a spot in a refugee camp, which is usually run by the host country in partnership with the United Nations and other international organizations. Refugee camps provide access to basic commodities like water, food, health care, and sanitation. They are meant to be temporary way stations en route to one of the three options that the international community advocates for forced displacement: voluntary return, local integration, or resettlement. Daniel, like the vast majority of people in refugee camps, would soon find out that none of these options were available to him.

When Daniel reached the Mai Aini refugee camp in Northern Ethiopia, he was reunited with Kedijah. He was outside Eritrea, living with a woman for the first time, and, initially at least, ecstatic. They lived together in a tent constructed from plastic. Older women in the camp adopted him, teaching him how to cook. Each month he picked up the one liter of oil and 15 kilos of sorghum that the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) provided, and he ground the grain to make injera, a sour pancake-like bread. After a few months, Daniel started asking around to find a job or continue his education, eager to build a new life in Ethiopia with Kedijah.

But although Ethiopia hosts the largest number of registered refugees in Africa—739,156 in 2015—it strictly limits their rights, barring them from attending higher-education classes or obtaining work permits. (The United Kingdom announced in September 2016 that it would give the Ethiopian government an aid package to create jobs, including for some 30,000 refugees—a fraction of the total refugee population.) Ethiopia’s laws also allow it to restrict the movement of refugees, which meant that Daniel and Kedijah were essentially confined to the camp. This made integration into a community in Ethiopia impossible, but they certainly couldn’t go back to Eritrea: People who return face imprisonment, sometimes in underground shipping containers. So they turned to the final official option: resettlement.

The UNHCR classifies 14.4 million displaced people as in need of resettlement, but less than 1 percent will actually be resettled, because not enough wealthy countries take in these refugees. The United States currently takes in the largest number of refugees via UNHCR of any country: 79,000 in 2015, of whom 1,596 were Eritreans. Daniel had survived torment and repression, but he was one of many competing in an invisible lottery. He and Kedijah concluded that their chances of being resettled were slim to none.

But they also hadn’t escaped Eritrea to live out their lives in a refugee camp next door to it. Like so many others, they felt that heading to Europe was the only way for them to actively construct their future. Together, they moved on from the refugee camp in Ethiopia to Khartoum, Sudan, the main gateway to cross the Sahara desert on the dangerous journey to Europe.

Sudan has received millions of dollars from the European Union over the past few years to prevent this human flow, with more funding in the works, even though the country is still run by the dictator and war criminal Omar al-Bashir. A 2014 Human Rights Watch report found not only that Sudan has failed to provide protection to refugees in its own camps but that Sudanese officials have collaborated with traffickers to abduct migrants. Reports have now emerged that Sudan is using the Janjaweed militias to round up Eritrean refugees and force them back to Eritrea, where they face certain imprisonment and possible torture. Sudan is among the seven countries from which President Trump has banned immigration or travel to the United States.

Thousands of people have hired armed smugglers in Khartoum to begin the first leg of an often-deadly trip. People die from lack of access to medicine, food, and water; in car accidents; and at the hands of their smugglers. The deaths of many Africans traversing the Sahara go unrecorded; there are no organizations or journalists in the lawless desert to count the bodies.

In 2009, when Daniel and Kedijah were in Sudan, a new danger was beginning to develop on the route: the large-scale kidnapping, brutalization, and extortion of Eritrean refugees at the hands of criminal networks in Sudan and Egypt. Eritrean refugees who paid smugglers to get to Libya found themselves instead trafficked and sold to gangs who held them in Egypt’s Sinai desert and engaged in systematic torture, including rape. These gangs then called the victims’ families and demanded high sums of money—typically around US$30,000—for their release. From 2009 to 2013, UNHCR estimates, the Sinai trafficking industry made $622 million, almost all of it off the bodies of Eritrean refugees.

None of this deterred Daniel and Kedijah.

In Khartoum, the couple found odd jobs like cleaning rich people’s homes and working at restaurants to save for the next leg of their journey. After talking to other Eritreans and weighing the risks, the couple decided that Daniel should head to Europe alone. Kedijah had relatives in Canada; they hoped she could travel legally by obtaining a visa and be spared the danger of the Sahara crossing. A year after uniting with Kedijah in Ethiopia, Daniel set out across the desert on his own.

The trip from Khartoum to Benghazi, Libya, took him through 1,388 miles of barren land. The heat was dizzying, pocking his skin with blisters and leaving a sharp pain in his throat from thirst. During the trip, Daniel saw decaying bodies and bones, the ruined skeletons of cars that had crashed because the drivers were high or careless—one unending desert graveyard. When he arrived in the coastal city of Benghazi, it hurt his eyes to look at the sea.

In 2009, 2.5 million migrants were making a living, primarily through construction jobs, in Benghazi and other Libyan cities like Tripoli. A much smaller number were pausing before attempting the sea passage to Italy. Daniel and roughly 200 other Eritreans paid a new fixer $1,400 each to take them across the sea to Italy. After the fixer collected their money, he vanished.

Daniel and some of the other men from his group decided to track him down. The fixer was well-known, and a taxi driver eventually led them to him. Daniel’s group kidnapped the fixer for several days. They beat him and demanded their money back. Daniel admits that he wanted to kill him, but others objected. In the end, they released him after three days and turned him over to the Libyan police.

But the fixer spent only a day in jail before getting out; Daniel thinks he had high-level connections. Once free, the man sent Daniel and his friends a message: “Get out of Benghazi in 24 hours or I’ll kill you.”

It was July 2010, and Daniel had been traveling for 25 months. At the time, Israel was a cheaper destination from Libya than Italy, because it is closer by way of smuggling routes through the Sinai: Some 45,000 Africans had arrived in Israel over the previous few years, the majority of them Eritrean and Sudanese refugees fleeing dictatorships. Daniel’s brother Beshir had been one of them, and after losing so much money on the failed attempt to reach Italy, Daniel opted to join his brother in Israel instead. “I would have rather died than ask my family for more money,” he says.

So Daniel set out again with different smugglers, nearing the Israeli border in about three weeks. He spent several hours in a holding cave with other Eritreans while the smugglers assessed the border. At a certain point, his group was told to make a break for it. Daniel and a friend started running across the desert with a woman carrying a 4-month-old child, trying to help her move as quickly as possible, when they heard gunshots: The Israeli border guards were shooting at them. Daniel lost sight of the others in the confusion and dust, but he had managed to cross into Israel, where he was immediately arrested and imprisoned.

When Daniel arrived, Israel was in the process of constructing a 150-mile-long, 16-foot-high steel fence to prevent African refugees from entering the country. Rather than respond to the refugee crisis at its doorstep with a humanitarian approach, Israel had chosen instead to militarize its border and increase the number of detention facilities. By 2013, the finished fence would result in an entirely sealed border. Israel’s fence was a sign of things to come: In July 2015, Hungary began unfurling razor wire across its borders to keep the refugees out. Other countries in Europe followed suit, negating one of the primary principles upon which the European Union was founded: freedom of movement. Across the Atlantic, President Trump has vowed to build his own wall to blockade refugees and migrants from Mexico and points south.

Daniel was eventually released from prison and allowed to join his brother in Tel Aviv. He arrived at his brother’s apartment to find five people sharing one small room. He’d imagined his brother living comfortably in his own place, removed from the horrors he had suffered. What he found instead was a different kind of pain: that of living in a country that doesn’t consider you a person.

Despite being a signatory to the 1951 United Nations Refugee Convention, Israel has largely refused to recognize the rights of non-Jewish refugees, and as of now, African refugees have no chance to gain asylum. The Israeli government has embarked on overtly racist campaigns against these refugees, resulting in widespread public xenophobia. For example, it uses the term “infiltrators” to describe Eritrean and Sudanese asylum-seekers and claims they’re a threat to Jewish identity. One government official described black refugees as a “cancer.” In Israel, Daniel developed psoriasis, a skin condition induced by stress; he still has it today. It started with small flaky patches on his arms but then spread, the trauma of being displaced manifesting itself across his body.

Even so, Daniel longed to bring Kedijah to join him in Israel. They had now spent a year apart, and he initially hoped that she had been united with her family in Canada as planned. But Kedijah was still stranded in Sudan.

Like a significant percentage of refugees worldwide, Kedijah had fled Eritrea without a passport. Eritreans who have done so struggle to obtain passports from their embassies abroad; the Eritrean embassy in Khartoum officially stopped issuing them in 2010. So when Kedijah applied for a Canadian visa to visit her family, she was rejected due to a lack of proper identity papers. Next, she applied for a visa to visit Daniel in Israel, but that was also denied.

Out of safe and legal travel options, Kedijah turned in 2013 to the very smugglers she had hoped to avoid. Given that Israel’s border was by then increasingly impenetrable, she chose to head for Italy, as she and Daniel had originally planned. The route through the Sahara is more dangerous for women, who frequently face sexual assaults from smugglers. Daniel didn’t know if he would ever see Kedijah again.

Alone in Israel and tired of living in an overtly racist country, Daniel fell into a severe depression. He worked underground at Eritrean restaurants to make money, but felt he was leading someone else’s life. In mid-2014, the Israeli Department of Immigration issued flyers announcing that refugees could sign up for a program that would relocate them in Rwanda. Daniel was skeptical, but the government promised $3,500 in cash and a paid flight. It was a chance for legal recognition, and there were rumors that African refugees would soon be jailed in Israel; things were getting worse, not better. Daniel decided to get out. “I knew nothing about Rwanda,” he recounts. “I knew it was bad, but better than Israel and Eritrea. I didn’t care.” In early 2015, Daniel said goodbye to his brother and headed to the airport.

The relocation program was part of the Israeli government’s larger effort to empty the country of its entire African-refugee population. Israel began creating agreements with countries like Rwanda and Uganda to accept the 45,000 African refugees in Israel, the majority of them Sudanese and Eritrean, in exchange for funds. It later announced that refugees who didn’t accept “voluntary relocation” or return to their country of origin would be imprisoned. Israel’s approach has been mirrored by others: In March 2016, the European Union entered a deal with Turkey to prevent more refugees from arriving in Europe in exchange for cash and other incentives; the agreement also allows the EU to deport refugees now in Greece back to Turkey. These arrangements violate the core legal protections given to refugees under international law, including the right not to be returned to a country where they’re unsafe or that doesn’t have a fair and efficient asylum system. Yet wealthy and powerful nations are increasingly ignoring international refugee law because they can; UN member states never put in place an accountability mechanism. A number of similar EU-negotiated deals are in the works in Africa and the Middle East to stem migration.

Daniel knew something was wrong shortly after his Turkish Airlines flight landed in Kigali, Rwanda’s capital. As soon as he and the 16 other Eritreans onboard stepped off the plane, uniformed Rwandan officials appeared and demanded their IDs. The men were then escorted to a private villa, where they were left overnight without their passports. The next morning, a government official informed them that they would be sent to Uganda. For the journey, they would have to pay the Rwandan government $150.

The men in Daniel’s group had heard reports of Eritreans being beaten and tortured by Ugandan police, but they had no choice: The officials took their cash and, several days later, loaded the refugees onto a minibus. The bus dropped them off several hours later at Uganda’s unmanned border, and the men continued on foot. Daniel had arrived in yet another country, delivered this time by government-sanctioned smugglers.

In Uganda, Daniel was still illegal. He filed for asylum, but was unsurprised when he never heard back. As the relocation stipend from the Israeli government dwindled, Daniel assessed his bleak future. The horrors of the past six years had gotten him nowhere.

Still, there was one piece of happy news: Kedijah had survived the desert and subsequent sea-crossing. A few weeks after departing Khartoum, she had contacted him from Italy. And now she was working in Rome at a charity, assisting other Eritrean asylum-seekers. They exchanged pictures across the distance on instant-messaging apps. Rather than accept his fate in Uganda, Daniel decided that he would again try to reach Italy. He still clung to the hope that, over there, it was possible to have a different kind of life.

Around August of 2015, Daniel traveled to Juba, South Sudan, where he spent one night and then moved on toward Khartoum. Once again, he paid smugglers to take him across the white plains of the Sahara to Libya, avoiding being kidnapped or sold. Libya had changed dramatically since his last visit, in 2009; it was now immersed in a civil war. In 2015, the Islamic State took over several cities on the coast, and many parts of Libya had become lawless. Refugees are now at risk of kidnapping, forced labor, and abuse. Daniel noticed these changes as soon as he arrived in Benghazi. He needed to get out of Libya as quickly as possible, but he also had to choose a fixer carefully to avoid being detained and tortured. Profits for smugglers operating in Libya alone are now estimated to exceed $325 million a year.

Daniel’s new fixer hid groups of refugees in caves outside the city to avoid detection by militias; he spent several weeks underground waiting for a boat. Day and night, it was common to hear gunfire in the distance. But the trip for which he was preparing is itself particularly grim. In 2016, nearly 4,600 people died trying to cross the Central Mediterranean from North Africa to Europe, making it the deadliest year on record. A significant percentage of these deaths were Eritrean refugees; others were from Sudan, Somalia, and other African nations. They pay smugglers to put them on flimsy, overcrowded boats that often disintegrate in the choppy water. Most people crossing, like Daniel, cannot swim. When the boats break, they drown.

When the time came for Daniel’s crossing, he boarded a plastic raft that took him to a medium-sized boat. He wedged himself onto the cold floor of the lower deck alongside hundreds of others. A little over an hour in, large waves began rocking the ship back and forth like a violent cradle. The smell of sweat and urine was already omnipresent; people started vomiting. Daniel prayed.

After six hours at sea, the Italian Navy intercepted the struggling vessel and rescued its passengers. In 2017, such rescue efforts may be in jeopardy, as the European Union increasingly looks for ways to police the sea. The newly named European Border and Coast Guard Agency (formerly Frontex) is working with NATO to disrupt smuggling networks, and it will start funding the Libyan Navy to contribute to the rescues. “We will not be Europe’s policeman for free,” said Mohamed Swayib, the head of Libya’s agency to control illegal immigration, in an interview in December 2016. Human-rights groups have already raised concerns that the EU’s funding will merely be used to trap and return refugees from the sea to Libya’s prisons. In 2017, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency’s budget is $281 million; the cost of an average visa to the EU is 60 euros, but Daniel could never have gotten one.

After his rescue, Daniel was taken to a small island off the coast of Italy. Two days later, in late October 2015, he arrived at the central bus station in Rome, where he found Kedijah waiting for him. Daniel did not know what to say. What had happened during the six years they were apart was inexpressible for them both. Daniel felt as though he were floating outside himself, looking down. Kedijah hugged him and wept. She still wore the delicate gold necklace he had given her in Eritrea.

Daniel and Kedijah now face an uncertain future. European politicians have tried to delegitimize pro-immigrant movements and erode asylum procedures. Far-right parties across the continent are gaining daily in popularity by calling for a whiter Europe, and the left has yet to offer a truly inclusive alternative. The European Union continues to scale up funding for repressive governments—including Eritrea’s—in the name of preventing migration, leading to more militarized borders within Africa that will spell danger and possible death for those brave enough to forge them.

The United States, meanwhile, is unlikely to resettle more refugees in the wake of the recent election, and other nations that have kept their doors open, such as Kenya and Jordan, are increasingly slamming them shut, partly in response to EU policy. Despite this fact, millions of desperate people will still defy the efforts of those governments and political parties that seek to keep them out. They don’t have any other choice.