We Need Radical Abundance

If we want abundance we have to ask, an abundance of what exactly, and produced under what economic logic?

Traditionally, critiques of bureaucracy take the perspective of the little man caught in the obtuse machinations of faceless corporations or an unyielding state. Kafka’s Joseph K., for example, or Catch-22’s Yossarian. Even The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy begins with protagonist Arthur Dent lying in front of a bulldozer to thwart an intransigent planning department. In recent years, we’ve seen the return of anti-bureaucratic mobilization, but advocates for “deregulation” in 2025 are more likely to be on the side of those employing the bulldozers than those lying in front of them. This apparent reversal of position results from a dramatic transformation in the nature of bureaucracy over the last 40 years. With democratic socialist mayors in New York and Seattle, the left needs to understand this change, the way it was engineered, and how we might enact a similar transformation in the opposite direction to deepen democracy.

2025 saw anti-bureaucratic mobilization across the political spectrum. On the right, we can point to Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) and its disastrous early-year rampage through the US public sector. But there were also centrist and “progressive” iterations addressing a similar mood. Last March, the growing YIMBY (Yes in My Back Yard) “movement” found its arguments codified in the best-selling book Abundance: How We Build a Better Future, written by liberal journalists Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson. They argue that overregulation—a surfeit of encumbering bureaucracy—has slowed economic activity, repressed living standards, and fed the rise of autocratic leaders like Trump.

Klein and Thompson construct a tragic narrative to explain this state of affairs. In the face of malpractice by governments and powerful corporations, well-meaning liberal activists “acted across many different levels and branches of government in the 1970s to slow the system down so the instances of abuse could be seen and could be stopped.” In the meantime, however, “much that was designed to foster grassroots participation has been captured by incumbents and special interests” who now hinder development.

The same line of argument informs the few policy prescriptions offered in the book. Their solution to economic stagnation involves a continuation of former President Biden’s policy of de-risking—the use of public money to incentivize private investment in sectors targeted by the government—but Klein and Thompson want to strip such mechanisms of the kinds of social and environmental clauses found in both the Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS and Science Act, the latter of which sought to enhance the inclusion of “women and other economically disadvantaged individuals in the construction industry.” They use the ugly neologism “everything bagel liberalism” to name this tendency of trying to tackle all ills at once.

The Democratic Party establishment has largely adopted this liberal abundance agenda as an oligarch-friendly answer to the economic populism of AOC and Zohran Mamdani. Regulatory de-risking has also found favor in the catastrophically unpopular UK government of Sir Keir Starmer, which has promised to reform planning laws to favor the country’s oligopoly of big developers. Yet the analysis behind this policy doesn’t bear scrutiny.

The idea proposed by Klein and Thompson that Ralph Nader is among the chief architects of contemporary bureaucratic practice is historically illiterate. In fact, the anti-bureaucratic sentiments of the 1970s were given their most effective political articulation by right-wing neoliberal theorists of New Public Management. Gordon Tullock, for instance, argued that government bureaucrats were incentivized into relentless empire building. “As a general rule,” Tullock asserts, “a bureaucrat will find that his possibilities for promotion increase, his power, influence, and public respect improve, and even the physical conditions of his office improve, if the bureaucracy in which he works expands.”

As social spending increased during the 1970s owing to worker militancy and democratic activism for Black civil rights and women’s liberation, government bureaucrats were accused of forming a de facto alliance with such groups to expand the state at the expense of taxpayers. The solution was a radical program of neoliberal institutional reform in which democratic accountability was replaced by the techniques of accountancy.

The autonomy of “bureaucrats,” and other workers in both the public and private sectors, has since been constricted by the practice of auditing activity against what are often quite arbitrary units of measurement, which can then be used for competitive ranking. When we interact with such structures, we must conform to their logic or lose out. Our forced engagement with these “market” mechanisms acts as a kind of training. It trains us to adopt a particular mode of thinking and acting. We are encouraged to game the system by shaping our actions to accord with the audit.

The institutions—and increasingly the algorithms—with which we daily interact are continually tweaked to ensure they reward ruthlessly competitive, selfish, and self-promoting behavior while penalizing those who behave in any other way. The organization’s original purpose often suffers as a result, but through repetition we internalize this institutional logic, come to anticipate it, and act accordingly, until it eventually structures our commonsense understanding of human possibility.

The next stage in this story is explained by English sociologist Will Davies, who argues that neoliberalism began to seek a more robust normative ethic to legitimate its practice in the early 1990s. “The task of government was now to ensure that ‘winners’ were clearly distinguishable from ‘losers,’ and that the contest was perceived as fair.” The “Third Way” center-left drank most deeply of this neoliberal Kool-Aid and became its fiercest advocates. They shifted neoliberalism away from the social conservatism of its early period to incorporate those elements of the feminist, antiracist, and gay liberation movements that could be aligned with consumerism and competitive labor markets.

It’s the rejection of this normative dimension of neoliberal bureaucracy that unites both the anti-“woke” aspect of Trumpism and the anti–“everything bagel liberalism” drive of Klein and Thompson’s abundance agenda. These distinct political articulations both speak to the collapsed credibility of an ethic based on the justness of market outcomes.

Neoliberal market reforms have driven the rise of monopolistic, rentier business models feeding powerful oligarchs who use their wealth to ensure government and regulatory capture. Similarly, the post-1970s drive for “deregulation” didn’t improve efficiency, and it certainly didn’t lessen the bureaucratic burden on everyday life. Beyond the performative culture of audit and ranking that blights us at work, we face the asymmetry in information and power that monopolistic private providers hold over isolated consumers—a relationship figured by what Mark Fisher memorably called “the crazed Kafkaesque labyrinth of call centers, a world without memory…where it is a miracle that anything ever happens.”

Trump’s answer to the failure of neoliberalism’s normative ethic is to replace the supposedly impersonal adjudication of bureaucracy and law with open corruption, personal enrichment, and clientelist displays of the impunity of power. Klein and Thompson’s solution is to sidestep questions of fairness and wealth distribution by gambling on growth at any cost. Rising economic growth would, at least in theory, allow living standards to rise without impinging on the profitability of capital and the wealth of the oligarchs.

But under current conditions—accelerating ecological deterioration and an economy structured to funnel wealth straight to the very top—the means of achieving abundance can’t be ignored. Klein and Thompson’s prescriptions won’t work on their own terms. De-risking the investments of asset management firms entrenches the inequality in wealth and power that’s inhibiting both rising living standards and action on climate change. Removing DEI and environmental conditionalities will simply accelerate that process.

The left must not be drawn into a defense of normative neoliberalism. It needs its own critique of contemporary bureaucracy and its own program of institutional innovation and reform seeking to reshape the field of politics. The institutional structures we build must develop the democratic capacities and sensibilities of the people who interact with them. The repressive overreach of Trump and Musk is creating the conditions for a popular anti-oligarch, pro-democracy politics.

Affordability has become the watchword of the US left, but it can’t, on its own, become the left’s orienting ethic. It must instead be the foot in the door for a longer project of rebuilding the social power needed to address the crises facing us. Building popular protagonism—in which, through democratic deliberation and collective action, the popular classes become the main characters in social re-transformation—is the task that can orient the left through the protracted work of anti-capitalist transition.

The cost-of-living crisis is a symptom of two more determining and intractable crises: accelerating ecological decay and long-term economic stagnation. If we’re to tackle both affordability and climate change, we must limit the amount of economic activity run under the logic of capital while expanding the range of activity governed by democratic logic—where the assets, resources, services, and industries we need to live are brought under social ownership and governance.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Zohran Mamdani, the mayor of New York City, has promised to “deliver an agenda of abundance that puts the 99 percent over the 1 percent.” That will require different means of achieving abundance from those proposed by Klein and Thompson. The left’s answer to inertial bureaucracy is democracy. Mamdani’s creation of a Mayor’s Office of Mass Engagement shows the way. We can build institutions that allow popular deliberation over what we need. This collective negotiation of shared interests is key to unleashing popular protagonism. The abundance we build must be radical in both form and content.

Support independent journalism that does not fall in line

Even before February 28, the reasons for Donald Trump’s imploding approval rating were abundantly clear: untrammeled corruption and personal enrichment to the tune of billions of dollars during an affordability crisis, a foreign policy guided only by his own derelict sense of morality, and the deployment of a murderous campaign of occupation, detention, and deportation on American streets.

Now an undeclared, unauthorized, unpopular, and unconstitutional war of aggression against Iran has spread like wildfire through the region and into Europe. A new “forever war”—with an ever-increasing likelihood of American troops on the ground—may very well be upon us.

As we’ve seen over and over, this administration uses lies, misdirection, and attempts to flood the zone to justify its abuses of power at home and abroad. Just as Trump, Marco Rubio, and Pete Hegseth offer erratic and contradictory rationales for the attacks on Iran, the administration is also spreading the lie that the upcoming midterm elections are under threat from noncitizens on voter rolls. When these lies go unchecked, they become the basis for further authoritarian encroachment and war.

In these dark times, independent journalism is uniquely able to uncover the falsehoods that threaten our republic—and civilians around the world—and shine a bright light on the truth.

The Nation’s experienced team of writers, editors, and fact-checkers understands the scale of what we’re up against and the urgency with which we have to act. That’s why we’re publishing critical reporting and analysis of the war on Iran, ICE violence at home, new forms of voter suppression emerging in the courts, and much more.

But this journalism is possible only with your support.

This March, The Nation needs to raise $50,000 to ensure that we have the resources for reporting and analysis that sets the record straight and empowers people of conscience to organize. Will you donate today?

More from The Nation

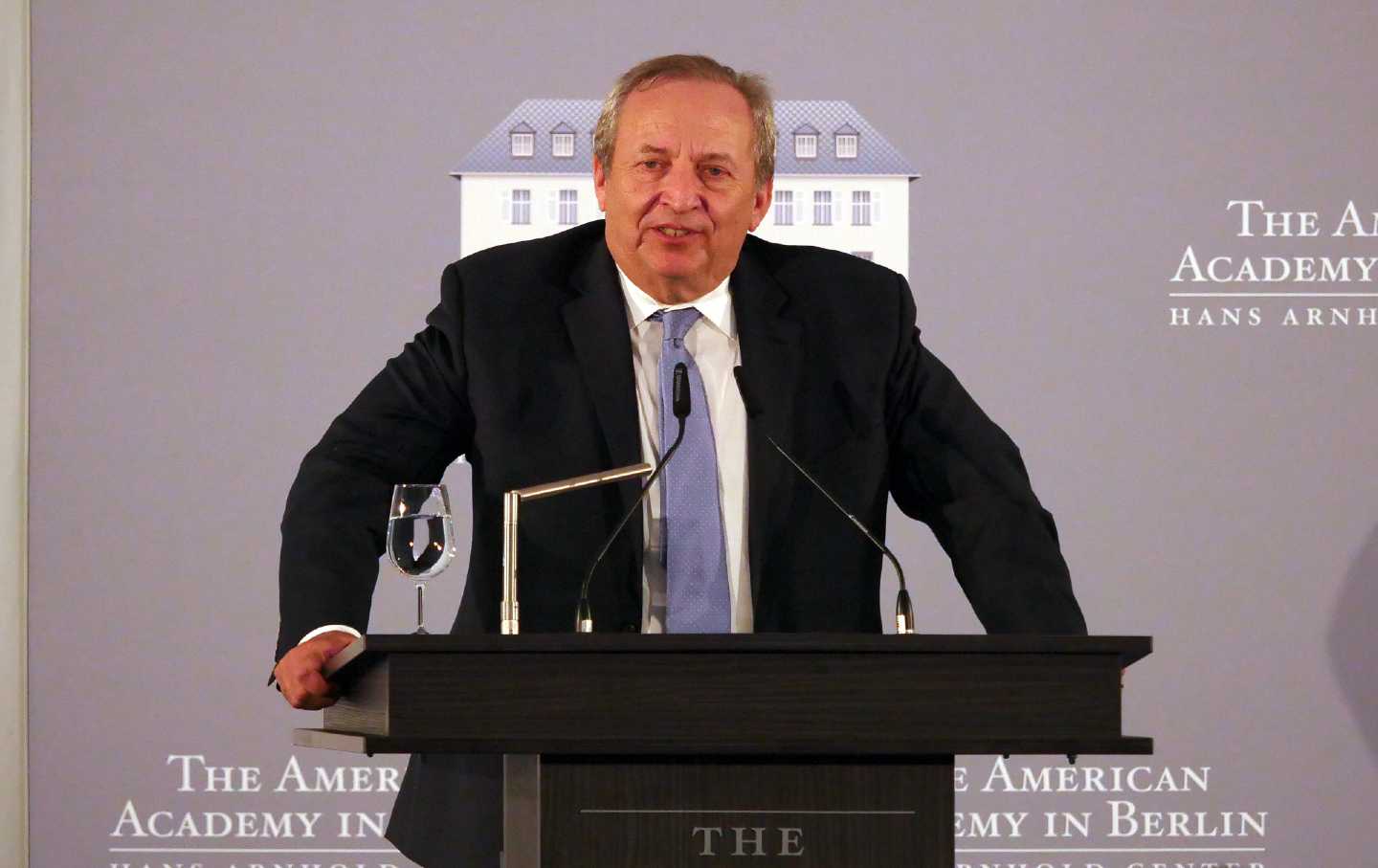

Larry Summers, We Knew Ye Too Well Larry Summers, We Knew Ye Too Well

The former Harvard president and Treasury secretary has resigned over humiliating disclosures in the Epstein files. But will that be enough to keep an ardent neoliberal down?

Binance’s MAGA-Branding Strategy Binance’s MAGA-Branding Strategy

The world’s largest crypto exchange often operates beyond the reach of the law. Now it’s helping to enrich the Trump family.

How Brothel Workers in Nevada Just Made Labor History How Brothel Workers in Nevada Just Made Labor History

The courtesans at Sheri’s Ranch were staring down a horrifying new contract. So they did what workers everywhere do: They got organized.

Don’t Let Trump Fool You. The Economy Is Bad, and He Is to Blame. Don’t Let Trump Fool You. The Economy Is Bad, and He Is to Blame.

The Trump administration’s efforts to distract from the bad economy just divert attention from one dumpster fire to another.

Why Elon Musk’s Latest Mega Merger Is Little More than Vaporware Why Elon Musk’s Latest Mega Merger Is Little More than Vaporware

The tech mogul and would-be space pioneer is mashing up his properties once more in a deal that's unlikely to achieve escape velocity .

The Farmland Revolt The Farmland Revolt

America’s farmers are fuming over Trump’s tariffs. Democrats need to channel their anger.