The Impossibly Intertwined History of the Americas

A conversation with Greg Grandin about his groundbreaking new book America, América: A New History of the New World.

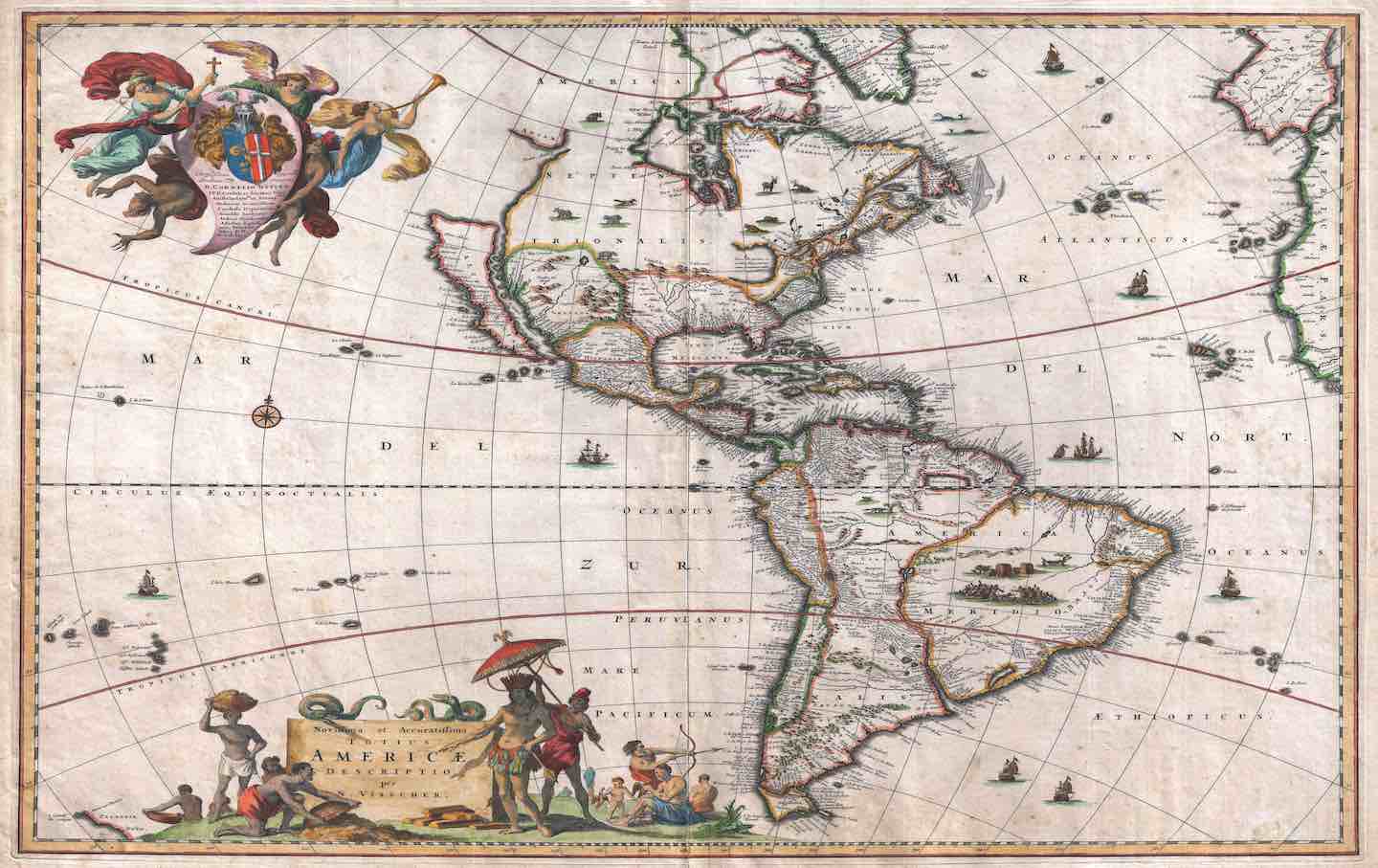

The “Visscher Map of the New World” including North and South America, 1658.

(GraphicaArtis / Getty Images)

A typical way of telling the history of the United States is to frame it as involving a series of key periods: Colonial America, the American Revolution, the Age of Expansion, the Civil War, Reconstruction, the Gilded Age, and so on. This is the way US history is typically taught in high schools and college survey courses, which usually present the country’s historical self-understanding and founding political identity in a rather self-contained way, with the exception of looking to Europe and England. The historian Greg Grandin challenges this approach to US history in America, América: A New History of the New World. It offers a groundbreaking 500 year history that shows how the United States’ identity and historical self-understanding are inseparable from those of Latin America—and in turn, it offers a comprehensive history of how Latin America was “indelibly stamped by the looming colossus to the North.”

In other words, Grandin argues that to truly understand the history of North and South America requires a hemispheric perspective of their long, complicated relationship from the very birth of the New World. And that is exactly what this book offers: a hemispheric interpretation of the Spanish conquest, the Age of Revolution in the 18th and 19th centuries, the Monroe Doctrine, the World Wars, and the coups and revolutions of the 20th century. He also illustrates how a more inclusive hemispheric perspective can enrich our understanding of the crisis of democracy that the United States is now experiencing, and how the history of Latin American resistance movements against authoritarianism offers solutions for the current authoritarian age.

The Nation spoke with Grandin about his approach to North and South American history, as it specifically concerns the legacy of the Spanish conquest, the differences between the revolutions for independence in the US and Latin America, how pan-Americanism inspired the League of Nations and the United Nations, the threat of fascist movements throughout the Western Hemisphere, both in the past and in the present, and what history teaches us about how they can be overcome. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

—Daniel Steinmetz-Jenkins

Daniel Steinmetz-Jenkins: Why don’t we start with the title of your book, America, América. What exactly do you mean by it? How does it relate to not only the hemispheric history you wish to tell but also the global history of the modern world?

Greg Grandin: The working title was “Greater America,” a riff off a famous essay from the 1930s outlining what a history of the New World might look like. But then one day on the subway someone started humming “America the Beautiful,” which got stuck in my head. At some point later, it hit me. America, América da da da da da da. The title has a nice mirror effect, capturing the sweep of the book—the history of the Spanish- and English-speaking Americas from conquest to present. And the argument itself. I spend some time on the politicization of the name America, how it came to be that English-speaking revolutionaries claimed the name America for themselves, even as Latin Americans insist that all the hemisphere is America. But I’m less concerned with fussing with names than understanding how five centuries of New World rivalry—first between Spanish Catholic and English Protestant America and then Latin America and the United States, over morality, religion, politics, law, and economics—shaped the international system and its discontents.

DSJ: You begin by offering a vivid historical narrative of the atrocious Spanish conquest of the New World starting in the late 15th century. Within a century, the conquest had led to the loss of 85 to 95 percent of the population, leading scholars to call it, as you mention, “the greatest mortality event in human history.” You then discuss the Age of Revolution in the 18th and 19th centuries, explaining how the New World broke free from the Old. What made the Spanish American wars of independence different, in your opinion, from that of the Anglo-American Revolution against Britain?

GG: Those insurgents who led the break from imperial Spain had a more robust understanding of history, and they understood their liberation movement as an atonement for the horrors of the Spanish conquest. Many of them, most famously Simòn Bolìvar but others as well, were inheritors to a powerful intellectual and moral critique of the conquest, that it was unjust, that the enslavement of Native Americans and African Americans was indefensible, that the colonial system was, as Bolívar put it, a ghastly fusion of ancient and modern despotisms. The authors of Venezuela’s first Declaration of Independence describe the Spanish arriving like “wild animals,” carrying with them Europe’s entire “history of bloodshed and perversity.” And the insurgent leaders understood themselves to be the products of such despoliation, and that citizenship would be granted to all inhabitants, at least in principle. “We are,” Bolívar said in 1819, “a sort of middle species between the legitimate owners of this land and the Spanish usurpers.”

No such historical awareness attended the American Revolution. For John Adams, America was “discovered,” not “conquered.” Colonialism was called settlement, and there was nothing about it to condemn. Grievance remained focused on what London did to them, the settlers, and no thought was given to including people of color in a common community, as Bolívar did.

As you say, the horrors of the conquest were immeasurable, and they sparked within Spanish Catholicism both a profound moral crisis and a philosophical revolution. The conquest continued unabated, but there emerged a coherent critique that was the beginning of modern political theory. The jurists, theologians, and priests who espoused these new ideas, the most formidable among them Bartolomé de las Casas, were a minority, to be sure, but they were influential—if not in stopping the killing and enslaving then in helping to advance what one scholar has called the slow creation of humanity. They insisted that the doctrine of conquest was no longer valid; that slavery, in all its many forms, was illegal, that all the world’s people, regardless of religion, customs, or skin color, were equal and possessed equal rights. Some argued to the point of pacifism, while others put forth a very thick description of social life, that individuals needed other individuals to survive—that society came before individualism.

But after the independence of the Americas, North and South, Latin Americans had to deal with an aggrandizing United States moving west like a whirligig taking Native America and Mexican land. So the problem that confronted Latin American independence leaders and their successors was how to contain the United States, The hemisphere’s first republic seemed more a force of nature than a new nation, possessed, as the Brazilian diplomat Felipe José Pereira Leal put it, by the “dizzying spirit of conquest.” More than one US founder said they could see no limits to its growth, that once they drove the natives beyond the Stony Mountains they’d soon fill both North and South America with Saxons. What to do with a nation that believed itself to be as universal as Christianity, as embodying the marching spirit of world history?

What Spanish and Portuguese Americans did was update the criticisms aimed earlier at Spain during the conquest and directed them at the United States. In so doing they sparked a revolution in international law.

DSJ: I was surprised to read the extent to which FDR’s administration feared a Nazi takeover of Latin America in the 1930s.

GG: Many thought so, in Berlin, Rome, Madrid, London, and Washington. Many in the Roosevelt administration thought that Germany would try to annex Argentina, Paraguay, or Uruguay. Secretary of Commerce Harry Hopkins was sure that if London fell, Germany would turn to Latin America before it turned its tanks on the Soviet Union: “The danger of delay cannot be overdrawn. Latin America, from Mexico down, is loaded with dynamite.”

Colonies of Germans living in Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, Chile, and Brazil considered Germany their true government. Their schools taught German racial theory and were filled with children who wore swastika armbands. Berlin, according to the left-wing popular front group the Committee for Pan-American Democracy, had plans to annex what it called “Antarctica Germanica,” which included the white majority government of South Africa and the Southern Cone governments of Latin America. The phrase “Unser Land Ist ein Stück von Deutschland!” (“Our Land Is a Part of Germany!”) began appearing on signs in shop windows and graffitied on factory walls in Uruguay and Argentina. The overseas outreach operation of the Nazis, the Auslands-Organisation, was active in southern South America, coordinating the activities of Nazi and fascist parties that counted thousands of members. German economic power was growing in the region, and fascists were making inroads in the region’s military and police. Peru’s government appointed an Italian general to head the Lima Police Department, who had previously worked with Italy’s counterpart to the German Gestapo.

Others pointed out the sociological similarities between Spain and Latin America—both regions dominated by large, landed estates dependent on servile labor threatened by militant peasant and labor movements—and feared that the Spanish Civil War would spread throughout Latin America. The same cleavages that Franco leveraged for his revolt existed in the Americas, but on a continental scale. The Mexican Revolution, constantly besieged by ultranationalist Catholic counterinsurgencies, including one supported by William F. Buckley Sr., was likewise compared to the Spanish Civil War. This is what the journalist Carlton Beals said at the time: “Spain has been the first big trench in the battle for our own continent.”

DSJ: What prevented it from happening?

GG: Fascism, or at least a Franco-like politicized right-wing authoritarianism, could very well have swept through Latin America in the years before Pearl Harbor, isolating the United States. But one of the things America, América is interested in is exploring the deep humanist, universal current of Latin American society, a current that has long stood in opposition to the darker side of the Spanish Catholic Empire, currents which gave birth to the first codification, in Mexico’s revolutionary 1917 Constitution, of what we now call social and economic rights. More simply put: social democracy.

Latin Americans are nationalists, and hold dear the ideal of sovereignty, but their nationalism is rarely the toxic kind that fuels fascism, but rather one that is imagined as a stepping stone toward a larger humanist universalism. For a century, this emancipationist tradition—which we might associate with the radical Enlightenment but also had deep roots in Catholic universalism—sharpened in antagonism to the United States, to its foreign-policy aggression, its Anglo-Saxon supremacy, its territorial expansion. But then, in the early 1930s, with the election of FDR in the US, opposition and contestation turned to convergence, as the US renounced the right to intervention and began, tentatively, to work with the region’s democrats and leftists. Some, like FDR’s vice president, Henry Wallace, imagined themselves building a continental New Deal. That policy abruptly changed course after the end of the war with the start of the Cold War, but for over the course of a decade, the hemisphere witnessed something of a social-democratic alignment. FDR’s close alliance with revolutionary Mexico was especially important, as was his alignment with Vargas’s Brazil.

DSJ: Can you elaborate on your claim that Wilson’s vision of the League of Nations has as its inspiration Latin America, and that FDR’s thinking about a United Nations is rooted in his prior thinking about Pan-Americanism?

GG: Latin America, in its break with Spain in the early 1800s, came into the world already a league, or community of nations, and they had to learn to live with each other. Its statesmen rejected the doctrine of conquest, which the US had revived to justify its drive across the continent. And they rejected Europe’s “balance of power,” which they held would always lead to war. Instead, they came up with a new foundation for international relations, one that held that nations were bound together by common interests, not by inherent competition. Within a short time, the region’s jurists had elaborated all the basic principles that would later go into the founding of the League of Nations and the United Nations: a rejection of doctrines of discovery and conquest; insistence on formal equality of nations despite their size; nonintervention; an outlawing of wars of aggression; and an insistence on impartial arbitration to settle disputes. Wilson repeatedly said that what he hoped to accomplish at Versailles (in its most idealist expression) was modeled on Pan-Americanism.

DSJ: Your book provides an enriching political and economic account of the early Cold War origins in Latin America of dependency theory—in short, the idea that economic underdevelopment is caused by the global economy being structured in such a way that is to the advantage of the wealthy core nations who exploit poor nations for their resources. I was surprised to read that dependency theory is inseparable from liberation theology—namely, a Catholic social teaching that suggests that God has “a preferential option for the poor.” How exactly are these two related?

GG: Friedrich von Hayek, among others, believed that you could trace the origins of libertarian economics back to Spain’s Salamanca School, a name for that group of theologians discussed above who questioned the right of Spanish dominion in the Americas. John Maynard Keynes, on the other hand, thought that the Salamanca School’s emphasis on “moral law” provided an important extra-economic customary check on accumulation. In any case, the interrelation of dependency theory and liberation theology took place more in the realm of politics and social relations than ideas.

In the 19th century, Christian socialist thinkers, many of them from France, had an influence on Latin American reformers and revolutionaries. In the 20th century, Catholic modernizers looked to do more than simply minister charity. They tried to explain the persistence of poverty. An important step in the formalization of what would become known as liberation theology took place with the arrival in Colombia of several anti-fascist Dominican priests associated with a Catholic renewal group called Economy and Humanism, which had been founded in Marseille in 1941 and was dedicated to the belief that the economy should serve humans, not humans the economy. One of these Dominicans became interested in political economy in the 1930s, while ministering in Breton fishing villages on France’s north coast, impoverished because they were unable to compete with an increasingly consolidated and more technologically advanced fishing industry. Lebret extrapolated a larger global economics from his experiences, one very similar to ideas later expanded on by Argentina’s Raúl Prebisch.

Later in the 1960s, it was largely Catholic intellectuals who created the study centers that would consider questions related to exploitation. “Dependence and liberation are correlative terms,” Father Gustavo Gutiérrez, the Peruvian credited with coining the phrase “liberation theology,” wrote. “An analysis of the situation of dependence leads one to attempt to escape from it.” Phillip Berryman, a Roman Catholic priest based in the 1960s in Panama City’s poor Afro-Panamanian neighborhood of El Chorrillo, recalls being thunderstruck when he first heard a critical economist making the case that the overdevelopment of Europe and the United States depended on the underdevelopment of the poorer regions of the globe. It “clicked right away—once you see it, it clicks,” Berryman said.

It was a potent mix. Faith and moral fire plus theorems and data added up to a belief that capitalism was a system devoid of virtue, and that God’s children deserved a life of dignity, not one subject to the punishments, plunders, and prizes of the so-called free market. It was not commerce that made one a more benevolent human, as some of the West’s moral philosophers would have it. Rather, insisted the theologians, psychologists, playwrights, and pedagogues of liberation, it was through politics—and especially through political dissent and struggle—that one became a more defined and empathetic individual, that one cultivated sympathies and solidarities, that one got a sense of one’s self in time and space, in history and the world.

DSJ: Much has been written about the so-called Chicago Boys, namely the group of neoliberal-trained Chilean economists responsible for brutal austerity measures initiated during Pinochet’s dictatorship. How, though, does a hemispheric perspective deepen our understanding of the neoliberal revolution in Chile and its legacy?

GG: A long hemispheric perspective helps us slip out of the prison house of ideas, to move beyond the notion that neoliberalism was sprung from the minds of a small cadre of Austrian economists and their followers. The Truman administration, and its business backers, would have liked to put into place something like what was later called neoliberalism as early as 1948 (and in some countries, like Peru, effectively did), but was stopped by the robust vision of social democracy discussed above, centuries in the making.

DSJ: You suggest that the political crisis that the US is currently experiencing might be tantamount to what the Idaho Senator Frank Church warned of when he spoke of the “Latin Americanization of the United States.” What exactly do you mean by the term and how is that now relevant?

GG: Church didn’t mean the phrase in a reactionary way, as it’s often used, to suggest that the country was losing its WASP identity and becoming mongrelized, or that plebeians were falling for strongman populism and lining up behind Latin American–like strongman caudillos. Rather, Senator Church, writing in 1975, two years after the overthrow of Allende in Chile, was worried that the United States was adopting a similar set of economic policies that were then being imposed on Latin America, what we now call neoliberalism. Some economists identify 1973 as the most economically egalitarian year in US history, with the smallest gap separating the rich and poor. But just two years later, the senator was warning about the regressive upward distribution of income, the strengthening of corporate power, and the inability of states to control and discipline capital. Church was prescient—for the restructuring of the United States wouldn’t be fully carried out until later, under Reagan and Clinton.

It’s relevant because this restructuring is the source of our current malady, the most immediate origins of Trumpism, the destruction of the New Deal social contract and the substitution of political hegemony with right-wing conspiracism, as the psychological war the US ran on other countries for decades was brought home. Every industrial, high-GDP country in the last decades of the last century took steps to restructure their economies in response to inflation, unemployment, rising energy prices, and global competition. Yet no other wealthy nation deregulated, outsourced, deindustrialized, and imposed austerity as gleefully as did the United States. And few did so while also gutting the institutions—welfare, unions, housing, farm communities, hospitals, mental-health care—that might have softened the blow. Clinton especially, during a period of unheralded economic expansion, with no contending challenger on the horizon of near comparable might—the Soviet Union was gone, wiped off the face of the map—ramped up police and prison spending and began targeting undocumented laborers. The United States’ political class treated the country as occupied territory and its citizenry as belligerents. That’s what Church, Cassandra-like, was warning about.

DSJ: Is it random that Miami is becoming what you call the “headquarters of a new World Right” or are there deeper historical explanations for the right-wing radicalization of Florida and this city in particular?

GG: You know, we often take Texas as emblematic of the nation’s trajectory, its history as a slave state and its prominence in right-wing oil politics providing a window into the national psyche. But Florida’s a contender. It entered the Union as the result of a rampage by Andrew Jackson, who cut a swath of terror through communities, killing Seminoles, refugee Creeks, and escaped slaves. Jackson’s main purpose was to pacify opposition to an enormous land grab he had carried out during the War of 1812, when he seized millions of acres from the Creeks. With that grab, Jackson, writes the journalist Steve Inskeep, “both created and scored in the greatest real estate bubble in the history of the United States up to that time.” Jackson made a fortune, as Creek tribal land was turned into Alabama slave plantations. I go into greater detail about this episode in the book, but, yes, there are deeper historical explanations, bound up in crime, corruption, bootlegging, and land swindling. Think of Nixon’s bagman, the shady Florida real estate developer Bebe Rebozo, or the CIA using the state’s swamplands as a training ground for Cuban and other anti-communist mercenaries. New York Times columnist Anthony Lewis called it a place of “morbidity and paranoia and fantasy” while Joan Didion, in her book Miami, said the arrival of anti-Castro exiles turned the state into one of “occult enchantment,” a fertile “complex of resentments and revenges and idealizations and taboos.” Today, ground zero of that enchantment, of those resentments and revenge fantasies, is Mar-a-Lago in Palm Beach, the command center of a hemispheric Trumpism.

DSJ: You talk often about the persistence of the social-democratic ideal in Latin America. How do you account for that persistence?

GG: It’s a paradox. Or a contradiction. When one considers the deep currents of reaction and dehumanization that exist in the region, how do we account for the opposite, the endurance of a profound humanism and sociality? “Humanism or barbarism” goes one version of the slogan, but in Latin American it’s been humanism and barbarism, with one a reaction to the other. One reason for the endurance of a humanist, social-democratic left, one absorbent enough to take in demands related to gender, race, and sexuality, has to do with, I think, the fact that Spanish colonialism’s moral crisis came early with the conquest. The critique launched by dissenters was frontal and all-encompassing, and when independence from Spain finally came, many of those who led that movement understood “emancipation” (even if they didn’t always act on that understanding) in its fullest sense, to include, potentially at least, all forms of oppression. And then there was the Spanish Catholic Empire itself, which claimed to be universal even as it created a colonial regime founded on the administration of difference. That reconciliation, of universalism and difference, both as an idea and a social reality, is, I think, the foundation of Latin American social democracy.

The Anglo experience was different. Evasion and denial were English settlement’s hallmarks. And remained so for centuries. No ethical dilemma accompanied the destruction of the continent’s indigenous people. When a moral crisis over chattel slavery did finally come, in the 1800s, it abstracted Black-skin bondage as a singular, exceptional evil. This, as the historian David Brion Davis wrote 50 years ago, had the “great virtue” of providing an “ideal” and “clear-cut” model of evil, which was useful for abolitionists when it came to fighting it but a hindrance to later historians and activists when they tried to relate it to the persistence of “other species of barbarity and oppression.” Latin America’s democrats have been more open (not all, to be sure, but an impressive many) to seeing the connections, to incorporating “other species” into a panoramic vision of struggle.

DSJ: It’s hard to imagine the last time that the Democratic Party was in a position of such weakness and ineffectiveness. You state, for instance, that “Wilson imagined a world without war. FDR imagined a world without fear or want. Today’s political class imagines nothing, as if they don’t expect the guns will ever fall silent.” As the Democrats are searching for a way out of the current darkness, how might the history you offer in America, América provide some much-needed light and inspiration?

GG: In the late 1940s, Chile’s ambassador to the United Nations, Hernán Santa Cruz, who worked on Eleanor Roosevelt’s draft of the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights, insisted that democracy would have to take up questions of political economy if it was to be more than a slogan. “Democracy—political as well as social and economic—comprises, in my mind,” he said, “an inseparable whole.” Despite the best efforts of the Chicago Boys and their death-squad adjuncts, most Latin Americans, judging from recent elections and polls, still define democracy as social democracy. Latin American democrats, of all stripes, have long confronted authoritarianism, and their luck depended on many variables, including whether Washington, as it did in the 1930s, stood with them, or, as during the Cold War, stood against them. But one constant, one lesson we can take from Latin America, is that you don’t beat autocrats by complaining about their autocracy. You beat them, as the hemisphere did in the 1930s and 1940s, by welding liberalism to a forceful agenda of social rights, by promising to better the material conditions of people’s lives. Nearly every Latin American nation, for instance, has the right to healthcare enshrined in their constitutions—a simple, clear popular objective that democrats in the United States should make the centerpiece of a campaign to make a more humane society.

Time is running out to have your gift matched

In this time of unrelenting, often unprecedented cruelty and lawlessness, I’m grateful for Nation readers like you.

So many of you have taken to the streets, organized in your neighborhood and with your union, and showed up at the ballot box to vote for progressive candidates. You’re proving that it is possible—to paraphrase the legendary Patti Smith—to redeem the work of the fools running our government.

And as we head into 2026, I promise that The Nation will fight like never before for justice, humanity, and dignity in these United States.

At a time when most news organizations are either cutting budgets or cozying up to Trump by bringing in right-wing propagandists, The Nation’s writers, editors, copy editors, fact-checkers, and illustrators confront head-on the administration’s deadly abuses of power, blatant corruption, and deconstruction of both government and civil society.

We couldn’t do this crucial work without you.

Through the end of the year, a generous donor is matching all donations to The Nation’s independent journalism up to $75,000. But the end of the year is now only days away.

Time is running out to have your gift doubled. Don’t wait—donate now to ensure that our newsroom has the full $150,000 to start the new year.

Another world really is possible. Together, we can and will win it!

Love and Solidarity,

John Nichols

Executive Editor, The Nation