Snapshot: Looking Backward Snapshot: Looking Backward

A Shinto priest at the Meiji shrine in Tokyo bids farewell to 2014. The shrine was visited by Hillary Clinton in 2009 on her first trip abroad representing President Obama as his secretary of state. It is surrounded by 175 acres of evergreen forest.

Jan 7, 2015 / Thomas Peter

5 Books: Who Polices the Police? 5 Books: Who Polices the Police?

Alex Vitale is an associate professor at Brooklyn College specializing in urban politics and policing. “Popular concern with policing has long been driven by high-profile tragedies,” he says. “What’s new is people organizing against more mundane forms of mass criminalization, like stop-and-frisk and ‘broken windows’ policing.” How should we understand these new battles? Vitale offers five starting points. PUNISHED Policing the Lives of Black and Latino Boys by Victor M. Rios Buy this book This powerful ethnography, a favorite of my students, tracks the corrosive effects of policing and the criminal-justice system on low-income young people of color in Oakland. Rios’s close connection with them allows him to tease out the ways in which they adapt to the constant harassment and humiliation of the “youth control complex,” on the streets and in school, enforced by the police. What often results is a vicious cycle of criminalization and incarceration, and these young men attempt to maintain their dignity in ways that often backfire, deepening their social and economic isolation. OUR ENEMIES IN BLUE Police and Power in America by Kristian Williams Buy this book This taut antiauthoritarian manifesto provides a well-researched overview of the oppressive nature of American policing. While sometimes engaging in generalizations and ad hominem attacks, its unapologetic indictment of the police provides a refreshing antidote to the liberal pleadings that police can be improved with a bit more training. Williams reminds us that the origins of American policing lie in racial oppression and class division. He looks to communities of revolutionary struggle—the IRA in Northern Ireland and the ANC in apartheid South Africa—for examples of self-policing. HUNTING FOR “DIRTBAGS” Why Cops Over-Police the Poor and Racial Minorities by Lori Beth Way and Ryan Patten Buy this book This groundbreaking study relied on hundreds of hours of police-car ride-alongs in two unnamed cities. While police often say that arrest rates are racially skewed because minority neighborhoods produce crime, Way and Patten found that officers looking to make arrests go out of their way to target people of color for drug violations and other petty crimes, often leaving their assigned patrol areas to “hunt” for such easy arrests. The book further proves that the “war on drugs” encourages the over-policing of communities of color. COP IN THE HOOD My Year Policing Baltimore’s Eastern District by Peter Moskos Buy this book This highly readable ethnography reveals the pointlessness of contemporary urban-policing practices. Most striking is its portrayal of the utter futility of the “war on drugs” from the perspective of both the police and low-income communities of color. Moskos gets deep into the origins of “vice” policing and describes in painful detail the corrupting influence of quotas and other numeric performance measures, showing how they produce unnecessary arrests, undermine relations between the community and cops, and devalue preventive policing. CITIZENS, COPS, AND POWER Recognizing the Limits of Community by Steve Herbert Buy this book This study of West Seattle demonstrates that so-called community policing expands police power rather than empowering civilians. Communities don’t have the organization or expertise to counter the bureaucratic weight of local police. Instead, police/community interactions become an opportunity for police to produce the appearance of cooperation while encouraging residents to provide information. Herbert’s findings suggest that demands for community control are doomed to failure, and that we should look to larger political structures to control the police.

Jan 1, 2015 / Alex S. Vitale

Stop Blaming Protests for Police Killings Stop Blaming Protests for Police Killings

While New York City mourns, political opportunists point fingers—but we should really be talking about reforms that would keep everyone safe.

Dec 23, 2014 / The Editors

A New Deal With Cuba A New Deal With Cuba

Caribbean détente, after a half-century of conflict.

Dec 23, 2014 / Peter Kornbluh

Why the Torture Report Won’t Change Anything Why the Torture Report Won’t Change Anything

At most, it only further proves the incompatibility of a secret intelligence service and an open democracy.

Dec 16, 2014 / Tim Weiner

The CIA Didn’t Just Torture, It Experimented on Human Beings The CIA Didn’t Just Torture, It Experimented on Human Beings

Reframing the CIA’s interrogation techniques as a violation of scientific and medical ethics may be the best way to achieve accountability.

Dec 16, 2014 / Lisa Hajjar

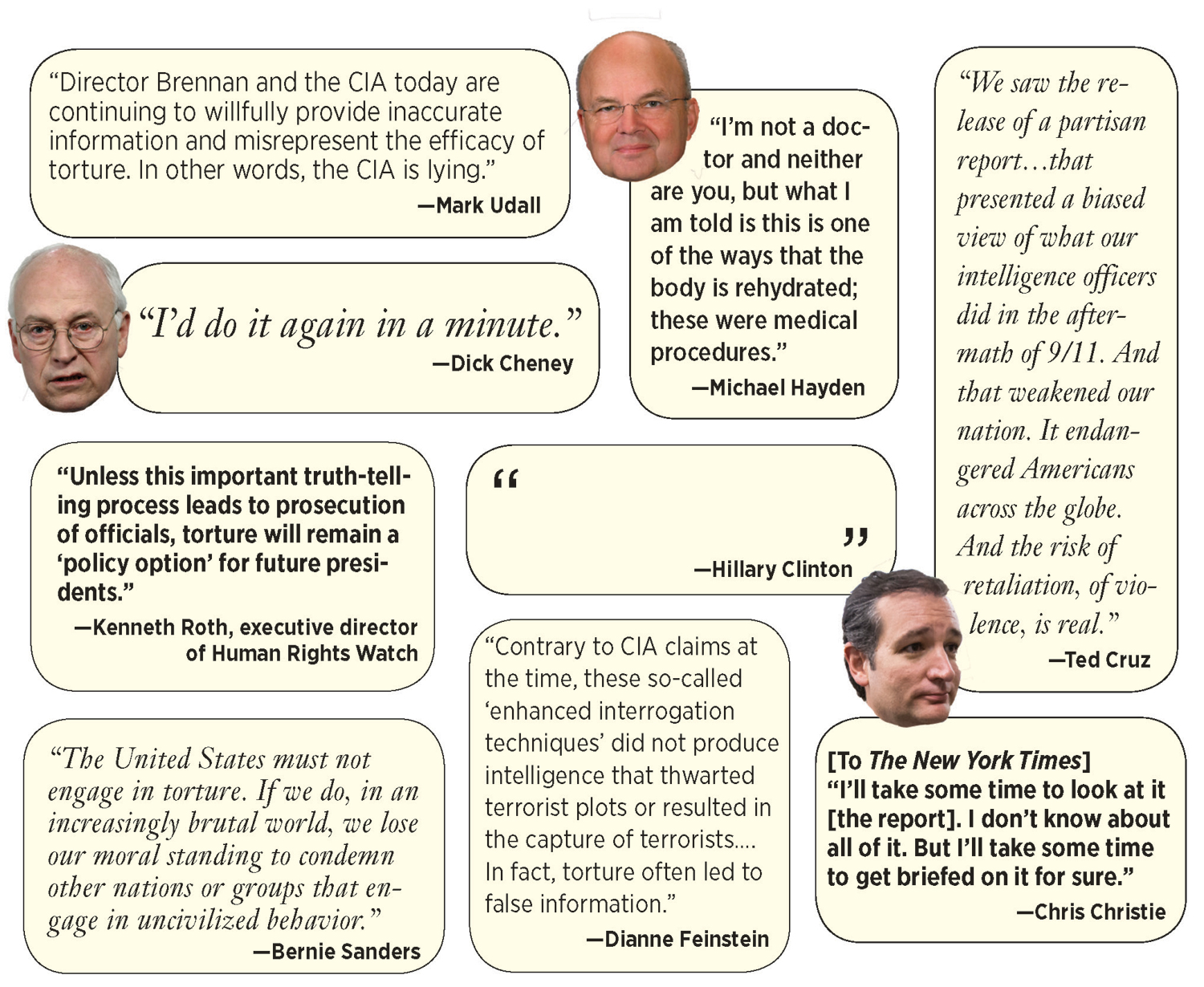

Tortured Words Tortured Words

Responses to the torture report ranged from angry to defensive to… silent.

Dec 16, 2014 / The Nation

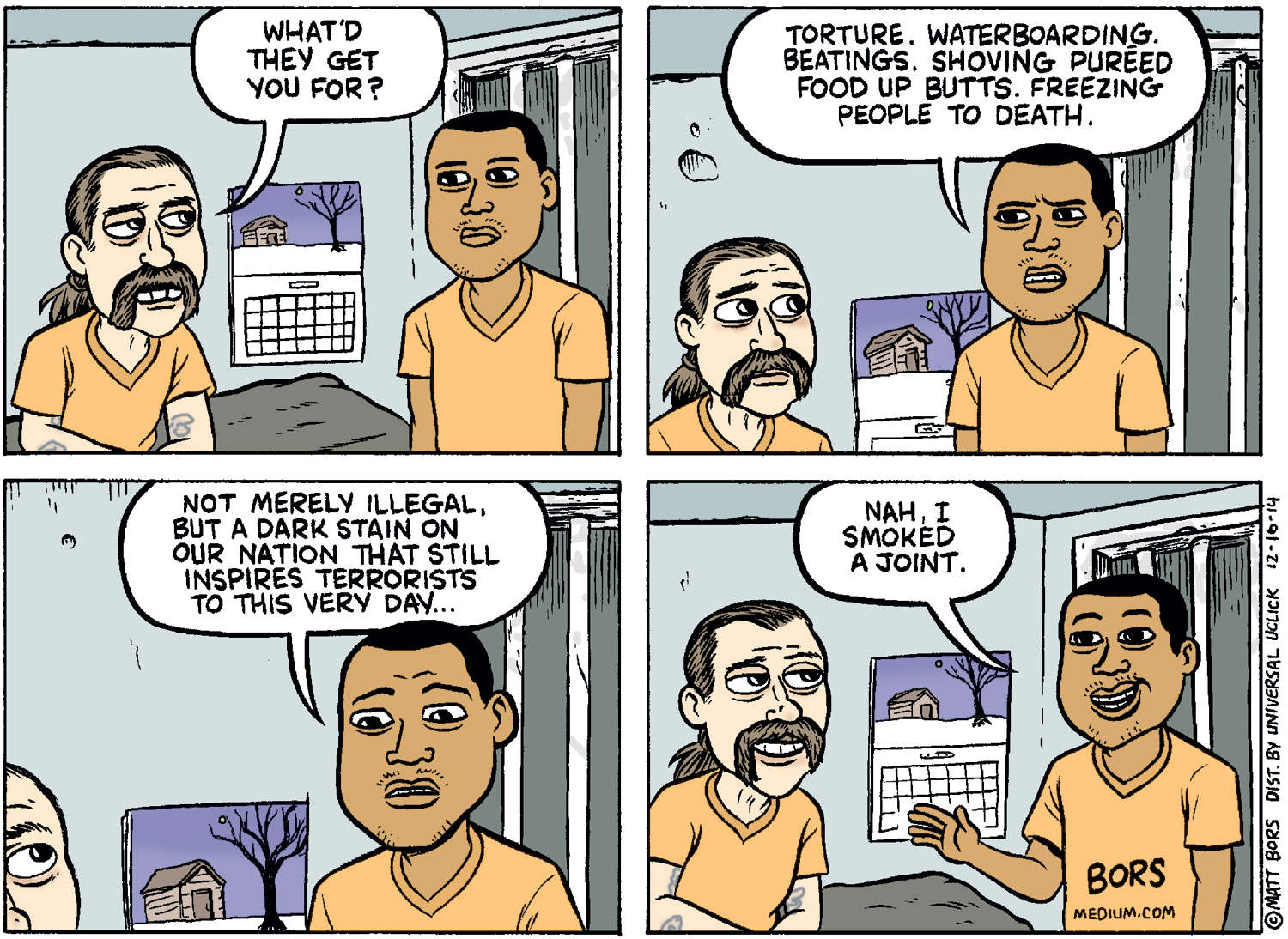

Comix Nation Comix Nation

Dec 16, 2014 / Matt Bors

It’s 1963 Again It’s 1963 Again

Last August, some observers drew comparisons between the fatal shooting of Michael Brown by Officer Darren Wilson in Ferguson, Missouri, and the 1955 murder of Emmett Till. The announcement on December 3 that a Staten Island grand jury had chosen not to indict the policeman who choked Eric Garner to death might indicate that we are closer to 1963—when a series of devastating setbacks and the subsequent widespread outrage transformed the civil rights struggle. There was a perfect storm this past month: the continuing fallout from a grand jury’s decision not to indict Wilson in Ferguson; the identical outcome in the Garner case; a Cleveland newspaper’s efforts to discredit and sling mud at the parents of Tamir Rice, a 12-year-old boy also killed by police. This moment has the potential to catapult change, just as a series of events did eight years after Till’s death. The 1963 murder of four black girls at Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church hit Americans square in the chest, reminding them of the Jim Crow system of justice in which black people had no rights that whites were bound to respect. The little girls were killed in September of that year in a place already dubbed “Bombingham” for the level of violent racist backlash against the city’s small progressive steps. Martin Luther King Jr. had been jailed there in the spring. Medgar Evers had been assassinated that summer in Mississippi. We find ourselves at a similar moment fifty years later—with “Again?” on our lips and a familiar feeling of horror at the video of Officer Daniel Pantaleo choking Garner to death, the unsparing force he uses against a man gasping over and over again, “I can’t breathe.” With the killings of Brown, Garner, Rice, unarmed New Yorker Akai Gurley and others, we are all reminded that black life is still devalued, and that police officers are too often treated as if they were above the rule of law. It is all coming so quickly: these announcements that a trial isn’t even necessary to determine a police officer’s guilt or innocence; these exonerations through other means. As a result, people are taking to the streets in Ferguson, New York City, Los Angeles, Atlanta, Boston, Cleveland and beyond. Please support our journalism. Get a digital subscription for just $9.50! To turn that outrage into progress, we should start to think big. A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, Ella Baker and other brilliant strategists of yesteryear knew that a successful struggle requires goals, not just reaction. Right now, activists from organizations like Millennial Activists United, the Ohio Students Association, Dream Defenders and Make the Road New York are demanding that the federal government prosecute police officers who kill or abuse people; that independent prosecutors be appointed at the local level and charged with prosecuting officers; and that the Justice Department deny funding to police departments that use excessive force or racial profiling. Several activists met with President Obama on December 1 to push these goals. This is beginning to look like playing offense. It’s worth noting that the public outcry in response to the rapid-fire events of 1963 is credited with making passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act inevitable. The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom had taken place not even a month before the Birmingham church bombing, showing the world that a critical mass of people were mobilized in the service of fundamental change. If the history of this country’s most revered period of revolutionary change is any guide—and if a policy program is developed to channel all this growing energy—then we’re just getting started.Dani McClain Read Next: Gary Younge on “black-on-black” crime

Dec 10, 2014 / Dani McClain