The US Government’s Plot to Murder Julian Assange

While dictators kill troublesome journalists with guns and missiles, democracies can afford to be more patient. But the end result is the same.

In most of the countries whose wars I’ve covered over the past 50 years, journalists were fair game. The first deliberate killing I remember took place during Lebanon’s civil war in May 1976, when a sniper shot Le Monde correspondent Edouard Saab. Saab, who also edited Beirut’s French language daily, L’Orient-Le Jour, had excoriated the Syrian regime for stoking Lebanon’s violence. While no one proved Syrian responsibility for his assassination, Syria did not bother to hide its role in the murder of another Lebanese journalist four years later. Salim al-Lawzi, a fierce critic of the Syrian regime, had fled to London when his magazine’s offices in Beirut were blown up. Yet he risked returning to Lebanon for his mother’s funeral. Kidnapped on arrival at Beirut Airport, he turned up dead a week later. His body had been disfigured in an unmistakable message: pens stuffed into his abdomen and his writing hand dissolved in acid. Other media critics, like Gebran Tueini and Samir Kassir of Beirut daily An Nahar, followed him to their graves.

The Syrians were not the only ones killing writers in Lebanon. In 1966, supporters of Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser murdered Kamal Mrowe, the esteemed editor-publisher of the Arabic daily Al Hayat. Mossad killed Palestinian writer Ghassan Kanafani in Beirut in July 1972, two months before I moved there. When I covered southern Lebanon for ABC News, Israeli soldiers killed several of my colleagues, claiming that their cameras looked like weapons. Between 2000 and 2022, Israel shot and killed 20 journalists in the West Bank and Gaza and the Committee to Protect Journalists in New York commented, “No one has been held accountable.” In October 2023, Israeli troops added to the total by killing Reuters videographer Issam Abdallah as he broadcast live from southern Lebanon. Iran, Egypt, Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, Muammar Gadhafi’s Libya and Saudi Arabia have also taken journalists’ lives. That’s just the Middle East.

In other regions where I’ve worked—among them Somalia, Eritrea, Indonesian-occupied East Timor, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and the former Yugoslavia—soldiers and politicians murdered journalists with impunity. There is barely a corner of the globe where reporters—apart from those taking the safer option of covering lifestyle, fashion, gossip, and the Kardashians—are not targets of the powerful forces they challenge. The United States presents itself as an exception, despite its toleration of friendly states, like Saudi Arabia and Israel, that have killed journalists. On World Press Freedom Day, May 3, last year, President Joe Biden declared, “Courageous journalists around the world have shown time and again that they will not be silenced or intimidated. The United States sees them and stands with them.”

Up to a point, Lord Copper. America did not stand with the reporters and camera operators from Al Jazeera, Reuters, and Spain’s Telecino in Baghdad when US forces fired on and killed them on April 8, 2003. Washington said the deaths were accidental, an explanation rejected by their colleagues as well as the Committee to Protect Journalists and Reporters Without Borders. The case that the killings were unintentional wore thinner in July 2007, when a US Apache helicopter killed a group of unarmed civilians on the streets of Baghdad. Among the dead were Reuters journalists Namir Noor-Eldeen and Saeed Chmagh. The Pentagon, which rejected Freedom of Information requests for the helicopter’s video record, said all those shot by the Apache were terrorists. Only WikiLeaks’ publication of the “Collateral Murder” footage, complete with the crew’s voiced glee at the killings, exposed the official lie.

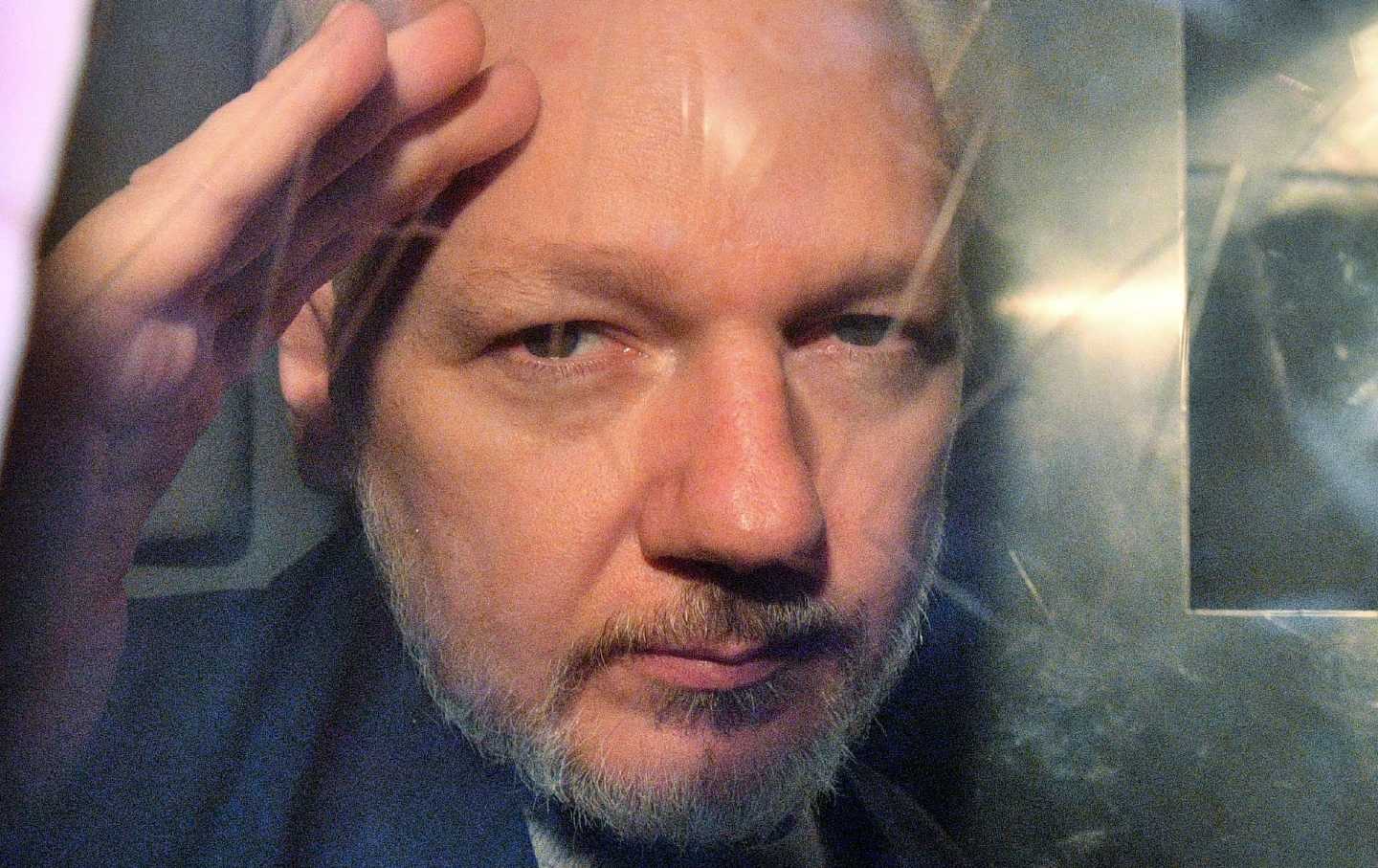

Third World dictators, not to mention Vladimir Putin, murder journalists as a matter of course. Western soldiers kill them in war zones, ostensibly without meaning to. Those actions are a far cry from, say, a democracy making plans for the premeditated murder of a journalist. Yet that, too, has happened. In March 2017, two months into Donald Trump’s presidency, WikiLeaks published CIA documents related to the agency’s “Year Zero Program” of massive, warrantless spying on American citizens and foreign politicians. The 8,761 CIA documents showed that the agency was wasting taxpayer money by duplicating a similar National Security Agency program and installing “Weeping Angel” bugs in consumers’ Samsung television sets to invade their privacy. WikiLeaks commented on what it called the “Vault 7” documents: “After infestation, Weeping Angel places the target TV in a ‘Fake-Off’ mode, so that the owner falsely believes the TV is off when it is on. In ‘Fake-Off’ mode the TV operates as a bug, recording conversations in the room and sending them over the Internet to a covert CIA server.” Someone with security clearance, realizing that the CIA listened to millions of Americans’ private conversations without their knowledge or approval, forwarded the files to WikiLeaks.

A Yahoo! News investigation last year revealed newly installed CIA Director Mike Pompeo’s swift and furious reaction: He instructed the agency to make plans to kidnap and murder WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange. Assange was already the focus of investigations by the CIA, the FBI, and the departments of Defense, Justice, and State over his publication in 2010 of the government’s own communications proving its culpability in war crimes. “But what really set Mike Pompeo…off was that Vault 7 leak,” Yahoo! News investigative reporter Michael Isikoff told Democracy Now!. “This was on his watch. This was his agency.” The campaign against Assange went into overdrive.

Pompeo appeared before the Center for Strategic and International Studies on 13 April to declare, “It’s time to call out WikiLeaks for what it really is: a non-state hostile intelligence service often abetted by state actors like Russia.” Defining WikiLeaks as a “hostile intelligence service” rather than what it is—a publisher—would legitimize any action the agency took against Assange. Except that it didn’t. National Security Council lawyers doubted the legality of killing Assange, and cooler heads within the CIA leaked the plot to the House and Senate Intelligence Committees. Meanwhile, the Spanish private security firm, UC Global, that monitored Assange in his refuge at the Ecuadorian Embassy in London, were told to prepare a kidnapping. One UC Global staffer, a “protected witness” in Assange’s appeal against extradition to the US, testified: “Specifically, the suggestion that the door of the embassy could be left open, which would allow the argument that this had been an accidental mistake, which would allow persons to enter from outside the embassy and kidnap the asylee; even the possibility of poisoning Mr. Assange was discussed, all of these suggestions.”

Yahoo! News wrote that kidnapping Assange in London “involved violating the sanctity of the Ecuadorian Embassy before kidnapping the citizen of a critical U.S. partner—Australia—in the capital of the United Kingdom, the United States’ closest ally.” One of Yahoo! News’ US intelligence sources indicated that the plan might have been carried out if Assange had been in a Third World country: “This isn’t Pakistan or Egypt—we’re talking about London.” The CIA had already kidnapped a Muslim cleric in Italy in 2003, indicating that the agency relegated Italy to the Pakistan-Egypt group rather than to the more exalted British class of nations. In 2009, an Italian court convicted 23 CIA operatives in absentia over the affair.

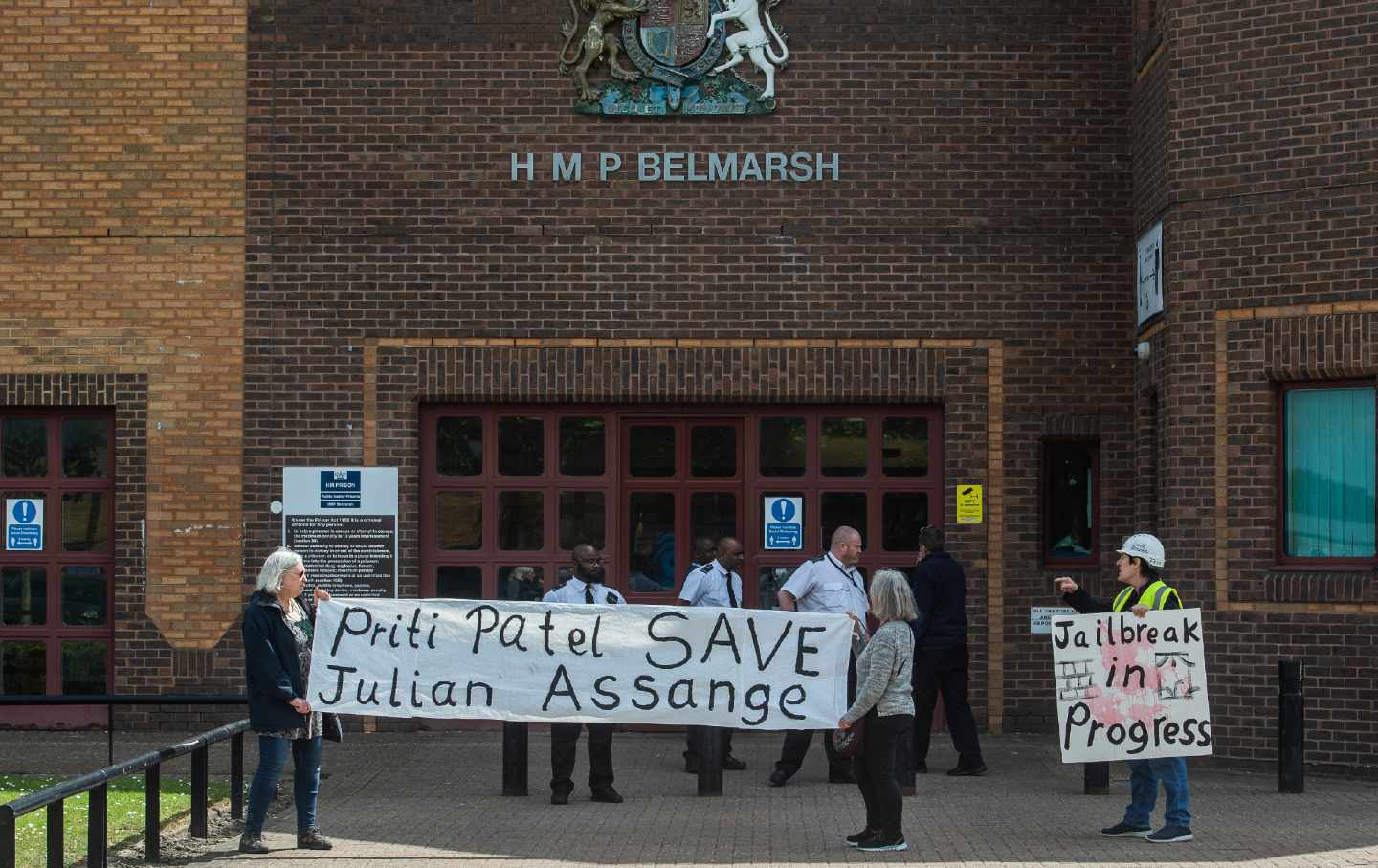

While the Trump administration dropped plans for Assange’s extrajudicial murder, neither it nor the Biden administration has turned away from killing him slowly in solitary confinement in Britain and, if the British appeals court agrees to his extradition, in an American super-maximum-security prison for the rest of his life. Physicians have testified that Assange, whose health is already jeopardized by the appalling conditions he has had to endure in London’s Belmarsh Maximum Security Prison since April 2019, risks suicide if he is sent to the United States. Britain’s High Court of Justice is considering the case, following hearings in February in which Assange’s counsel introduced evidence about the CIA’s earlier intent to kill him. The intention remains the same; only the means have altered.

On the occasion of last year’s World Freedom Day, Biden said, “Today—and every day—we must all stand with journalists around the world. We must all speak out against those who wish to silence them.” What will he say this year?