We Need to Modify—Not Trash—Oregon’s Trailblazing Drug Decriminalization Law

Measure 110 made Oregon the first in country to decriminalize all drugs. The law was poorly implemented and should be changed, not discarded.

A person holds drug paraphernalia near the Washington Center building on SW Washington St. in downtown Portland, Ore., on April 4, 2023.

(Dave Killen / The Oregonian via AP)As 2023 winds down, perhaps the West Coast’s most innovative—and controversial—public policy experiment is on life support.

Three years ago, amid the public health crisis of the pandemic and increases in drug usage, Oregon voters passed Ballot Measure 110, the Drug Addiction Treatment and Recovery Act, with 58 percent voting in favor. The law decriminalized personal possession of all categories of drugs, making the state the first in the country to remove law enforcement from the equation around hard drug usage.

Advocates argued that it would free up money for treatment and social-service interventions—the measure allocated upwards of $260 million from tax revenues on legal marijuana to treatment and addiction services—and would end the criminalization of poor, disproportionately minority residents. It was sold as a win-win for commonsense criminal-justice reform and, in the wake of George Floyd’s murder and the protests that grew out of that horrific event, as a step forward for racial justice.

The results didn’t quite work out the way proponents had hoped. In the last three years, the number of fatal drug overdoses in Portland soared. In 2021, alone, 41 percent more Oregonians died of fatal fentanyl overdoses than died in 2020. The steep upward trajectory continued over the succeeding two years as well. In 2023, nearly one in every 500 visits to emergency rooms and urgent care centers in the state were due to opioid overdoses, almost double the rate in 2019.

And, while advocates argue that the spike in deaths occurred before most of BM 110’s provisions kicked in, the public, looking at the nexus of crime, homelessness, a spiraling mental health crisis playing out in public view, and rampant on-the-streets drug usage—all of which were driving businesses, tourists, and convention organizers from the center of Portland—has rapidly soured on the policy reform. Their concerns have been backed up by some studies that show that the legalization of hard-drug possession can be linked to nearly 25 percent of the overdose deaths the state was seeing.

Many local governments also came out against the measure, arguing that, without adequate backstopping from the state, it was forcing them to divert dollars from their general funds into services to treat a soaring number of addicts. (It’s difficult to determine whether this was because the measure had created more addicts or if existing addicts were finally getting the services they needed and should have been provided with long ago.) A state audit found that it took the Oregon Health Authority two years after passage of BM 110 before all counties in the state had received at least some state funds for the increased treatment infrastructure that the measure mandated. In the intervening two years, counties had been left largely on their own.

With the troubled rollout of BM 110 and its treatment provisions, the public’s patience wore thin. By this past summer, nearly two-thirds of the state’s voters told pollsters they wanted to significantly modify the reform.

Not surprisingly, Oregon’s political and business leaders have gotten on board the anti–BM 110 train. This past September, two voter initiatives were filed that would ban the use of hard drugs in certain public locales; recriminalize possession of a number of drugs, including methamphetamine, heroin, and fentanyl; and mandate treatment for those with substance abuse issues instead of simply suggesting it. The initiatives, which will be voted on in 2024, are backed by an array of high-profile business leaders, including Nike founder and philanthropist Phil Knight.

Also, this past September, the Portland City Council unanimously voted in favor of an open-use drug ban. Those who continue to use drugs in public spaces can be fined or sentenced to jail.

Now, a growing number of legislators are putting public pressure on Governor Tina Kotek to call a special legislative session to address Oregon’s addiction crisis and to push for reforms to BM 110. And Kotek herself has, in recent months, repeatedly talked about the need to modify the ballot measure. (In a similar move, California Governor Gavin Newsom, reading the political tea leaves last year, vetoed a bill that would have created safe-use, supervised drug injection sites in several Californian cities. And earlier this year, Washington Governor Jay Inslee backed away from legalizing the possession of hard drugs.)

It’s hard to see how BM 110, its support corroded even among many of the groups that initially supported it, survives intact going into the 2024 election season. What comes next—whether it’s a good-faith modification of the law that keeps the principle of dealing with addiction as a public health issue rather than primarily as a law enforcement one, or a wholesale dismantling of all its key parts and a reversion to the War on Drugs model—will shape how progressive communities respond to the fentanyl catastrophe for years to come.

Turning the ship of state at least moderately against the failed, cruel, and calamitously expensive War on Drugs policies of the 1980s, 1990s, and early 2000s—policies that locked up huge numbers of low-end drug offenders, often for years and decades at a stretch—has been one of the great achievements of criminal justice reformers in recent years. That something of a consensus has been reached among politicians from across the fractious ideological divides of modern politics is nothing short of a political miracle. But it’s a fragile accomplishment. Oregon’s Ballot Measure 110 was a poorly thought-out and even more poorly implemented policy. In the accelerating backlash against it, by a mostly liberal electorate, there is a real risk that vitally important changes will also get trashed.

More from The Nation

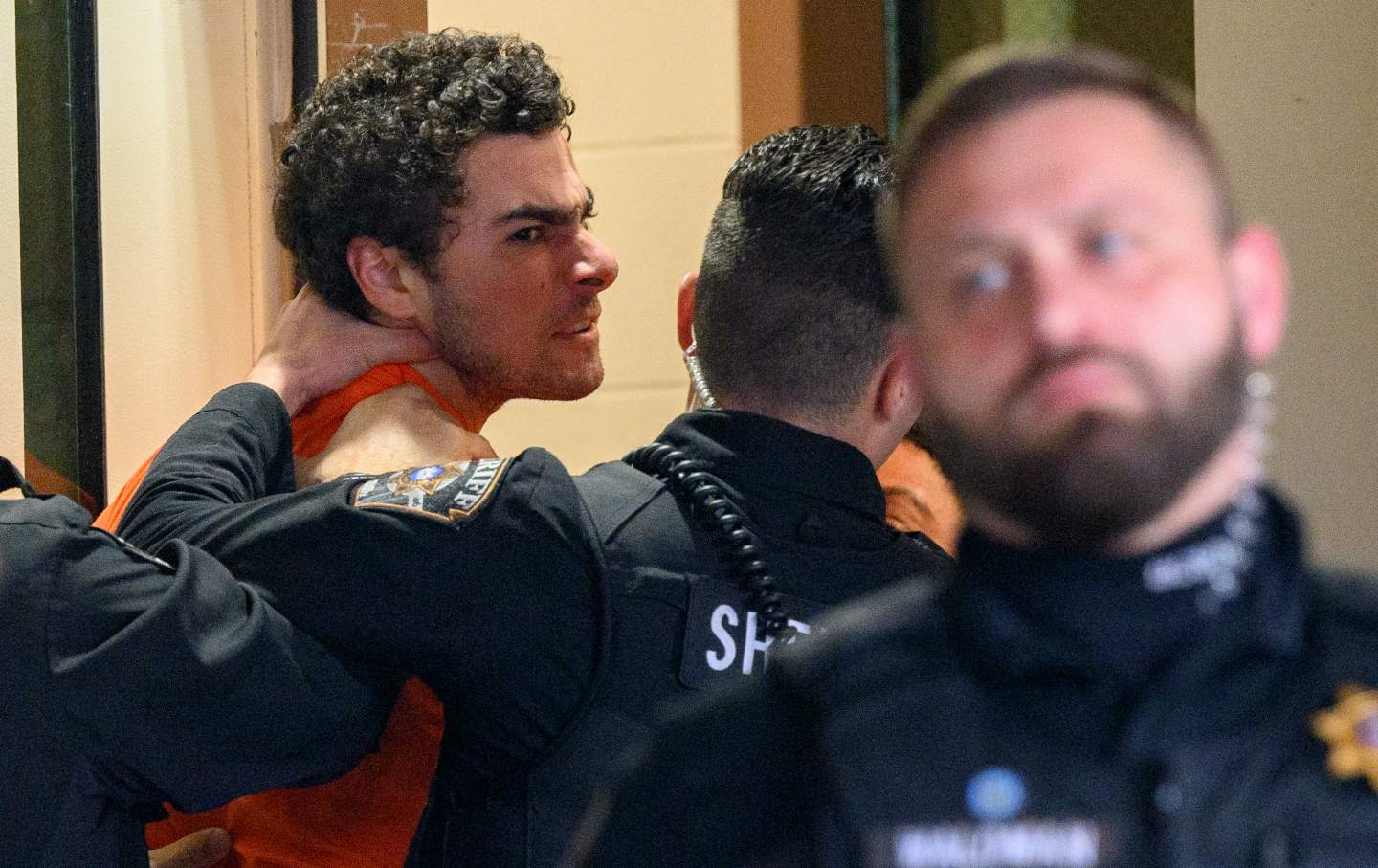

What Luigi Mangione and Daniel Penny Are Telling Us About America What Luigi Mangione and Daniel Penny Are Telling Us About America

When social structures corrode, as they are doing now, they trigger desperate deeds like Mangione’s, and rightist vigilantes like Penny.

Banning Trans Health Care Puts Young People at Risk of Harm Banning Trans Health Care Puts Young People at Risk of Harm

Contrary to what conservative lawmakers argue, the Supreme Court will increase risks by upholding state bans on gender-affirming care.

It’s Still Not Too Late for Biden to Deliver Debt Relief It’s Still Not Too Late for Biden to Deliver Debt Relief

Four years after hearing the president promise bold action on student debt, most borrowers are still no better off, and many—especially defrauded debtors—are measurably worse off....

It’s Been a Tough Year. Let’s Help Each Other Out. It’s Been a Tough Year. Let’s Help Each Other Out.

There may be a dark shadow hanging over this year’s holiday season, but there are still ways to give to those in need.

Prison Journalism Is Having a Renaissance. Rahsaan Thomas Is One of Its Champions. Prison Journalism Is Having a Renaissance. Rahsaan Thomas Is One of Its Champions.

Thomas and his colleagues at Empowerment Avenue are subverting the established narrative that prisoners are only subjects or sources, never authors of their own experience.

Luigi Mangione Is America Whether We Like It or Not Luigi Mangione Is America Whether We Like It or Not

While very few Americans would sincerely advocate killing insurance executives, tens of millions have likely joked that they want to. There’s a clear reason why.