Time to Stop Running

NFL running backs are in the same fight as all laborers: the struggle to be treated as humans, not “cattle.”

The 21st-century labor movement is as much a fight for existence as it is a fight for wages and benefits. If there is a common thread in the battles from Hollywood to UPS to Starbucks, it is the refusal to be seen—to use Angela Davis’s phrase—as “disposable populations.” These clashes are best understood as the opening salvo of a generational fight against the hedge funders’ belief in their own infinite value. Laborers on the other hand, whether because of artificial intelligence, automation, or job scarcity, are seen as expendable.

The rage that workers feel over being told they live a life of inevitable redundancy has reached the National Football League—and at one of the sport’s most glamorous positions. The NFL has become pass happy, which has had a ripple effect down the payroll. Running back, once a position of legends, is now a place where violent careers end early, and star players are quickly replaced with the sentimentality of a Michael Bay film. But in an unprecedented move, NFL running backs have been privately meeting over Zoom and publicly speaking out about the fact that they are dramatically underpaid relative to other players on the field and possess notably worse job security than their teammates. The position has a striking lack of staying power even for a league that players have nicknamed “Not For Long.”

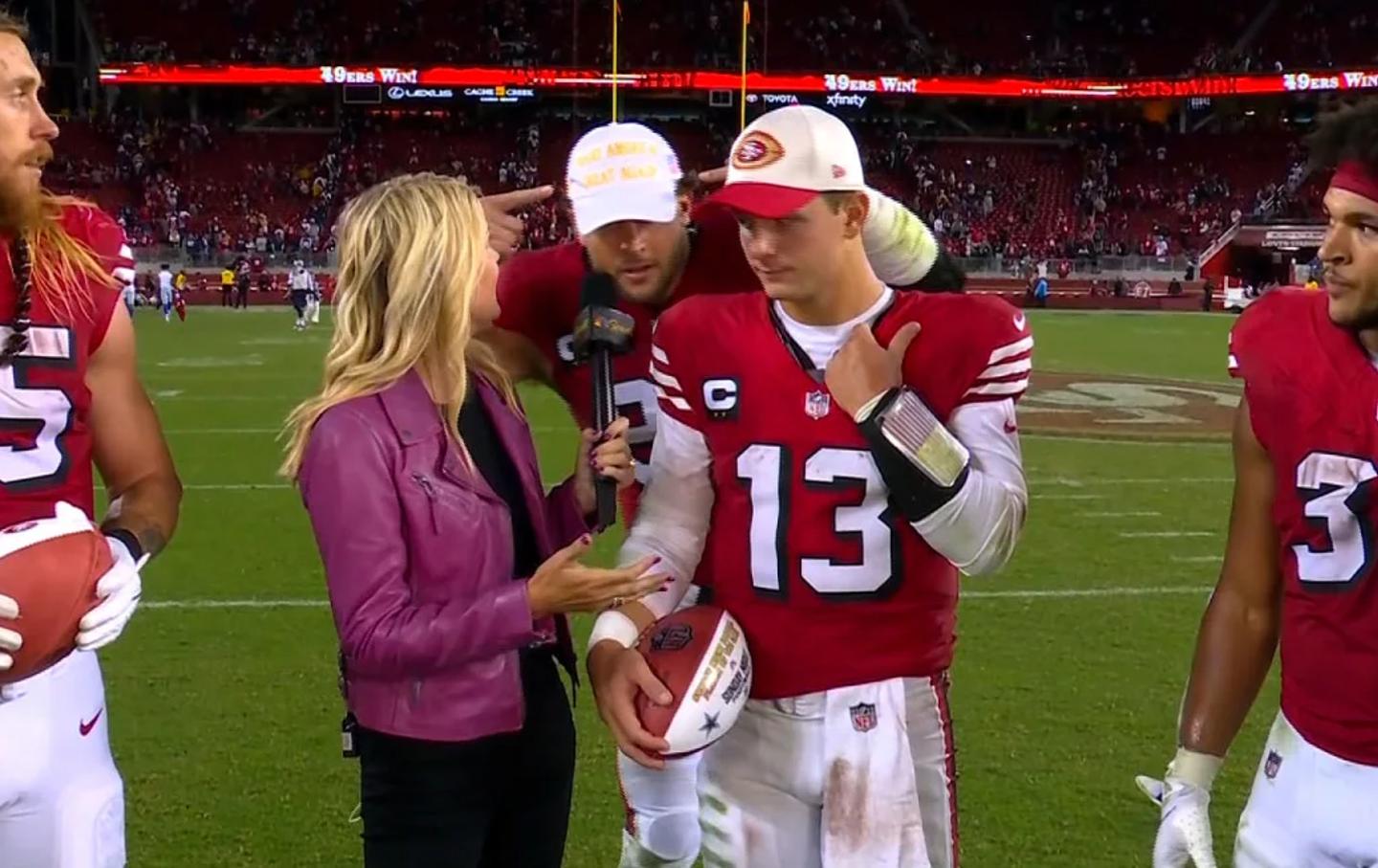

Speaking out are some of the most high-profile names in the sport—Pro Bowlers like Derrick Henry, Christian McCaffrey, and Saquon Barkley. They are sick of being seen by coaches and executives like used cars: assets that depreciate in value every moment they are on the field. Pro Bowler Austin Ekeler said, “Everyone knows it’s tough to win without a top RB, and yet they act like we are discardable widgets. I support any RB doing whatever it takes to get his bag.”

The mantra among GMs on running backs is that you can always get another. Star runner Dalvin Cook who rushed for 1,173 yards last year for the Minnesota Vikings at age 27, can’t, as of this writing, find a team. Another star runner, Joe Mixon of the Super Bowl–contending Cincinnati Bengals just re-signed for half his previous salary. The alternative would have been getting cut. But this collective anger of the runners started with Barkley, one of the most dynamic players in the game. In the New York Giants Pro Bowler we have a team leader who couldn’t get a decent contract despite being inarguably the best player on his team and the fact that Daniel Jones, the mediocre quarterback Barkley spent last season carrying on his back, just signed for $160 million.

But this week Barkley chose not to hold out or even miss a single day of training camp. He signed instead for one year at $11 million. No one will need to hold a benefit concert for Barkley, but this was a chance to try to flex some collective power in the face of an industry committed to his obsolescence. It was a chance to push back on being treated in a manner that recalls what Hall of Fame Dallas Cowboys executive Tex Schramm allegedly once said of all players, “You guys are cattle and we’re the ranchers. And ranchers can always get more cattle.”

In addition, Ekeler’s commenting, “I support any RB doing whatever it takes to get his bag” is a not-so-subtle call to hold out and wildcat against this state of affairs. But herein lies the problem of being classified as expendable. Running back is a job where sitting out a year doesn’t make the team see your value in a sharper contrast. It just means in the eyes of management that you are one year older and more easily shown the door. Only a broader movement involving more players and more solidarity can get them the remuneration they deserve, especially relative to the physical punishment that makes careers so painfully short.

After Barkley’s meager settlement, the wind may be a bit out of the balloon, but the fight is far from over. If running backs can keep up the energy and organize in a public way beyond social media, they will find their struggle resonating far more than they may have imagined. What is the SAG-AFTRA strike if not a stand against being classified as cattle, their humanity transformed by technology into little more than intellectual property? What are the labor battles at Amazon about if not being seen as “disposable”? If the running backs can work with these other strikes and struggles, they will find that they do not walk—or limp—alone: We are all living in a decaying system whose minders insist on their own infallibility, even as they drive millions into abject despair. May the running backs hear the call of labor: It’s time to stop running.