Texas Abortion Laws Haven’t Stopped Amy Hagstrom Miller

Despite having to move the clinic out of Texas, the founder of Whole Woman’s Health continues to fight for abortion access in the new “border states.”

On Saturday mornings Indian Bazar, a small Indian grocery in town, has fresh samosas, and Amy Hagstrom Miller, the founder and CEO of Whole Woman’s Health, is determined to pick some up.

Wearing a black Feminist Buzzkills podcast T-shirt, green sweats, and blue Hokas, Hagstrom Miller leads us out of her kitchen and into the car. Her distinctive dyed hair is maroon and blonde today, her glasses wickedly sharp.

Leisurely shopping in relative anonymity is a luxury she gained living in Charlottesville,Virginia, where she moved from Austin, Texas, 10 years ago after her husband took a job at the University of Virginia. In Texas, she was the face of the abortion rights movement. In Virginia, at least at first, she enjoyed some anonymity.

In 2016, the abortion provider she founded, Whole Woman’s Health, was launched into the national spotlight as the plaintiff in the landmark case Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, in which the Supreme Court ruled two provisions of a Texas law were unconstitutional because they placed an “undue burden” on people seeking abortions. The case set a national precedent against laws that target abortion providers with regulatory burdens that other healthcare providers don’t have to meet. In 2021, Hagstrom Miller’s clinic was again the lead plaintiff in Whole Woman’s Health v. Jackson, the case that challenged Texas’s Senate Bill 8, which banned abortions after six weeks and established a financial incentive for private citizens to sue those who help others obtain them. For decades, Whole Woman’s Health has been on the front lines of abortion care access in states where that access is now threatened.

After the fall of Roe in 2022, Whole Woman’s Health has been forced to close its Texas and Indiana clinics. Since then, Hagstrom Miller and her staff have been working to find new places in what they call “border states” to open clinics more easily accessible to women in states where abortion is now illegal. “We’re just waiting to see where we should go next,” she says.

Walking through Indian Bazar’s aisles, Hagstrom Miller points out spices and vegetables that you can’t get anywhere else in town—green chili peppers, instant chai tea, cardamom seeds, frozen medu vada. The floor is stacked with large containers of crispy snacks and big bags of rice.

Stores like the Indian Bazar and a few others—an Asian market, a Latin mercado—became touchpoints for Hagstrom Miller during the pandemic. Her friends and her work were mostly out of state and only reachable over Zoom. “I didn’t have anything here,” she says. She, her husband, and their two children were all working or going to school from home. So, searching for new communities and new experiences in Charlottesville, she sought out the city’s many international grocery stores. There’s C’ville Oriental, which has “six kinds of amazing tofu” as well as frozen dumplings and dim sum dishes—plus all the squash and hot peppers you need to cook spicy, flavorful dishes that she hasn’t been able to find anywhere else. The same is true of the Indian Bazar, where Hagstrom Miller buys ingredients for a chutney she plans to bring to dinner with friends that evening. “I had fruit and now I’m having a samosa—it’s a good Saturday,” she says as we hop back in the car.

After a short drive down the highway, Hagstrom Miller turns off onto a small street, where Charlottesville Whole Woman’s Health is located. The clinic is a small, welcoming house on a street of several such healthcare centers.There’s a “private property” sign to deter protestors, though Hagstrom Miller says there aren’t often many at this location. When Whole Woman’s Health bought the clinic in 2017 from another, more traditional abortion provider, she moved the entrance from the back to the front.

Since Dobbs, she says, the license plates in the parking lot are increasingly from out of state—North Carolina, Georgia, West Virginia, Tennessee—as abortion becomes illegal across the South. The clinic was supposed to be open today, she says, but it was short on medical staff. They had to reschedule patients. “Even in Virginia, supposedly a haven state, we still have trouble securing enough doctors and nurses,” she says.

In her work, Hagstrom Miller is often straddling two worlds. One part of her has to navigate the demands of a private business and the regulatory environment of health care. But she also needs to be in movement and advocacy spaces, to remind advocates, activists, and policymakers what abortion care providers on the frontlines of care need.

It can be frustrating, she tells me as we pull into the Costco gas line, to feel all but forgotten when it comes to federal funding and donors. During court cases, like Hellerstedt, donations flooded to legal organizations; meanwhile, abortion providers like Whole Woman’s Health struggled to stay afloat.“We were self-funding our ability to stay open,” she says.

She’s been working on strategies to make Whole Woman’s Health’s model sustainable. One of these is advocating for federal funding from the Biden administration, something like a FEMA or a PPP for abortion care providers who are having to close and reopen clinics to keep up with the patchwork state of abortion’s legality.

“The last three Supreme Court plaintiffs—Whole Woman’s Health, June Medical, and Jackson Woman’s Health—we all self-funded ourselves to move our clinics to different states,” she says. “You can’t have that.”

The daughter of a builder and the sister of an architect, Hagstrom Miller thinks in terms of space. Her house is light-filled, the morning sun pouring into a kitchen with a large, angular island. The walls of her home office are painted a welcoming, warm purple. This attention to aesthetic, space, and mood extends to her philosophy for Whole Women’s Health clinics. “One of the things I come to the work with is, how does an environment communicate warmth or comfort? Or distress people?” she says. “So our clinics have a lot of homeyness to them. We turn off the ceiling lights and turn the lamps on and think about the temperature.”

There’s a block of storage units in Charlottesville where what remains of Whole Women’s Health’s four Texas clinics that didn’t end up in their new Albuquerque location is stored—everything from ultrasound machines to wall décor. Watching a life’s work get packed into boxes and shipped across state lines to where the political and regulatory environment is more welcome was disheartening, Hagstrom Miller says. She remembers how, on a few occasions, staff members flying from Texas to the clinic’s new location in New Mexico for appointments realized their patients were on the same flight—the same patients, the same doctors, the same nurses, and even the same equipment, all displaced to another state.

As we unload the groceries, Hagstrom Miller begins pulling out the materials she’ll need to make chutney for dinner tonight—knife, cutting board, blender. She’ll use the grated coconut we just bought, some peppers, some coconut milk, some coriander, some garlic. The chutney will be a side dip for the samosas we bought at the Bazar.

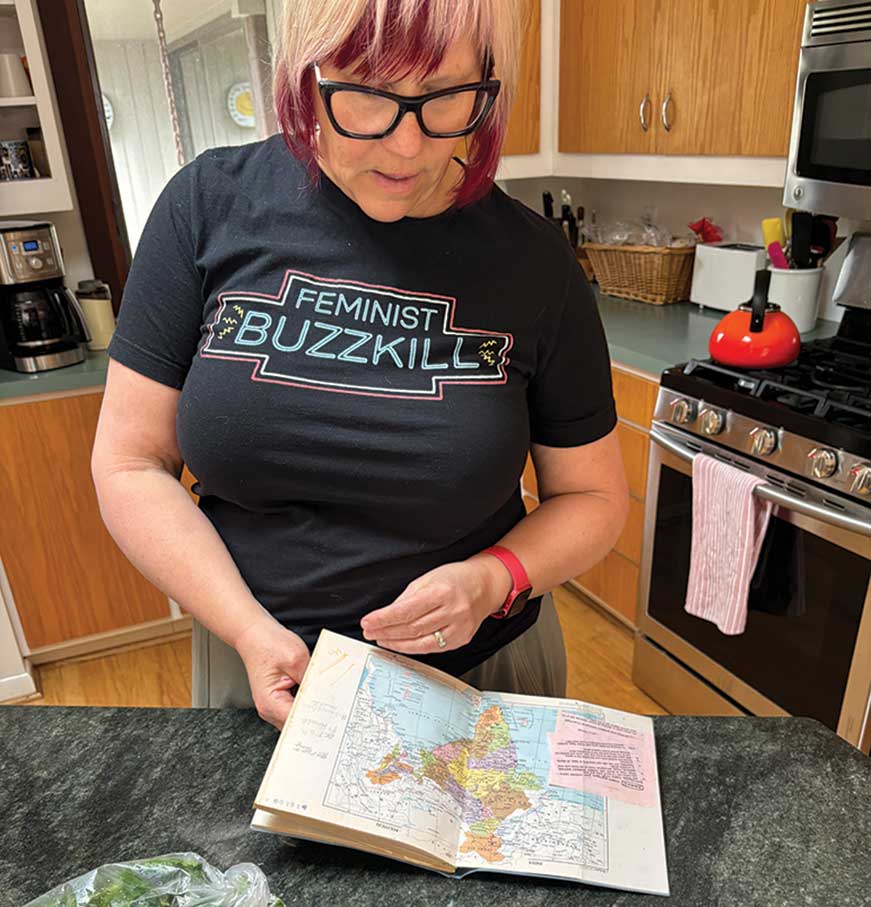

Cooking Indian cuisine has been an important pastime for Hagstrom Miller ever since, as a 21-year-old college student, she studied abroad in South India, where her host mother was a caterer. “She taught me to cook, and she would invite all the neighborhood ladies over to judge and taste my food until I passed,” she says. The recipe is in the same navy blue notebook from her time there in 1988. “The front part of it is the research I did when I was there,” she says. “And then in the back are the recipes that I wrote down.” The pages are stained from years of use. She flips to page 131: The recipe contains a list of ingredients and very few instructions.

She starts slicing small green chilis that she’ll put in the chutney. “I usually take the seeds out or they will kill you,” she says, coughing and laughing as she scrapes out their insides. “I already felt that go into my lungs.” Next, she turns to the garlic.

Hagstrom Miller traces her politics and her understanding of human rights back to this time in her life, when she lived in India, during her senior year as a religious studies and international studies major. For decades, India had the equivalent of an equal rights amendment. “But the actual experience of rights that people had in their lives was very different,” she says. Her freedom—even a white woman—was circumscribed by her gender. She stayed in at night, because when she went out she was followed and groped. Her host sisters, who she interviewed for the project, were even more restricted, though they were educated and “on the cusp” of Westernization. She read feminist theory for the first time in India, and gained a new perspective on the United States’s destructive foreign policy in the leadup to the Gulf War.

As she swishes the long green stalks of coriander around in water,, Hagstrom Miller tells me about what brought her to abortion care. “I’m very much a learn-by-doing person,” she says. “I come to abortion from a human rights framework. So I’ve learned a whole bunch about business in order to run really good clinics; I’ve learned a lot about health care, medical billing, and all that stuff; I’ve learned a lot about litigation to fight back against law. But it’s all in service of this central nugget of having clinics that can treat people with dignity and respect, in this human rights framework.”

All the ingredients now in the blender, she starts pulsing it. The mixture turns a vibrant green—a very different color than the chutneys she’s had in the United States, which she believes use fewer chilis. “In India, I couldn’t eat it for months. They had to cook separate food for me until I practiced a little.” She gives me a taste. It’s spicy, bright, pleasant.

The morning quickly turns into afternoon, and Hagstrom Miller’s dogs are barking outside in the sun. Her teenage son and husband pass through the kitchen hoping for a bite to eat. Before I leave, she takes me into her office. On the wall is a dry-erase map of the United States, where abortion is banned, where it’s still legal, and where its future is uncertain. She’s using the map to plot out potential locations for future clinics on what she calls “the new borderland”—maybe southwest Virginia, or southern Illinois. That’s a long-term problem, though, a problem that will still be there next week, next month, next year. The contents of the storage units are waiting for their next home, she says. In the meantime, she has the day-to-day business of abortion care to worry about. But tonight is for dinner with friends, for fresh chutney and samosas on a warm almost-spring night.