Last summer, getting vaccinated was promoted as the most fun, fashionable, sexy thing a person could do. Free vaccines and boosters were a centerpiece of the Biden administration’s policy and its messaging. The sense of hope, progress, and even hookups enabled by vaccines was crystallized in the upbeat single “Vax That Thang Up” by Juvenile—perhaps the only credibly sex-positive Covid-related US public health message to date. Iconically, the video featured scenes from a pop-up vaccination site, with a health tech/backup dancer in a face shield and the rapper Juvenile “making it rain” with white CDC vaccination cards. The unsung hero of that cultural moment, of course, was the significant federal expenditures underwriting national vaccine supplies.

Unfortunately, that ethos of good vibes and abundance has apparently reached its sell-by date, even as the United States puts new Omicron boosters on tap. Recently, Coronavirus Response Coordinator Ashish Jha announced that the federal government will end its expenditures for Covid vaccines, treatments, and tests this fall. The popular federal program that sent Americans free at-home Covid tests was then shuttered on September 2. But to judge by the tenor of recent public comments, you’d think the good times were still rolling. Last month, Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona stated that the new and much more limited CDC guidelines for Covid in schools should provide “students, parents, and educators the confidence they need to head back to school this year with a sense of joy and optimism.” In his comments on the end of federal funding, Jha stated, “My hope is that in 2023, you’re going to see the commercialization of all of these products.”

To be sure, none of this seems like particularly joyful, hopeful news. The United States will be among the first countries to cease the provision of free Covid vaccinations and treatments, leaving low-income people—a group that is overrepresented among the pandemic’s victims—with even less protection. After free vaccination ends, as Neil Sehgal—a health policy scholar at the University of Maryland—commented, “We’ll enter a phase where we can virtually wipe out deaths among the well-insured.” The inequity that this implies is no cause for celebration, and there is no guarantee that Congress will support the White House’s most recent pandemic spending request, either. As funding for vaccines dries up and CDC guidance gets stripped down to the studs, the message is—remarkably—still all about optimism. If the Biden administration is offering up a shot of austerity, it is chasing it with a tonic of toxic positivity.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

It’s easy to understand why the Biden team would want to remain upbeat, given its efforts to spin the administration’s challenges with the messages “We did what we said we would do” and “Covid no longer controls our lives.” But glossing over the nation’s Covid death toll—which, on the eve of the 9/11 anniversary, is currently equivalent to another Twin Towers attack every week—won’t help procure the resources needed to control the pandemic. Over the past year, we’ve seen a worrying pivot from aspiration to acceptance in pandemic policy—with CDC and White House officials normalizing high levels of death and other poor outcomes rather than articulating a road map for reducing them to the lowest possible levels. In one grimly underachieving gesture, earlier this year administration officials internally debated precisely what number of deaths per day might be acceptable to the public.

The official response to these outcomes has been, effectively, a policy of no policies. Since spring 2021, US leadership has issued increasingly threadbare and permissive Covid guidance, such as allowing people who test positive to exit isolation after a mere five days—even as mounting evidence shows that most continue to test positive beyond that limited window. Local authorities—caught between a public repeatedly told the pandemic is over and feckless national leaders—have been left to figure things out for themselves. The policy vacuum around Covid is compelling businesses, child care providers, camps, and church committees to make decisions that should rightfully be made by national institutions, as health care policy experts Wendy Netter Epstein and Daniel Goldberg recently wrote.

If calls to “follow the science” dominated in 2020, policy-makers and pundits are now pivoting to follow the public—or a cherry-picked version of public opinion. Polling data shows that most of the public—though fatigued by a pandemic that has dragged into extra innings—continues to support commonsense Covid measures. But despite enduring public enthusiasm for vaccine and mask mandates, officials are claiming to “meet the public where they are”—or to be “adopting the status quo as policy platform,” as physician Eric Reinhart recently put it. This kind of reticent, hands-off attitude suggests that policy-makers themselves are unwilling to spend their political capital—and may also prefer to address inflation, supply chain shortages, and the looming midterm elections. Republican obstruction has also been a key factor in preventing better Covid policy—yet Democrats have been more eager to imbibe the elixir of good news than to call out the GOP’s role in undermining public health.

Increasingly scanty federal guidance on Covid—call it Covid policy lite—has also been spun as a way of empowering states and localities to make their own decisions. As BA.5 once again sent cases climbing, Ashish Jha said, “Local jurisdictions—cities, counties, states—should make decisions about mask mandates because communities are different and their patterns of transmission are different.” Yet it’s clear that the administration prefers some local decisions above others. When mayors in Philadelphia and Los Angeles announced mask mandates earlier this year, for example, some administration-aligned pundits took to opinion pages and other media to criticize city governments for doing exactly what Jha had called for: making their own policies.

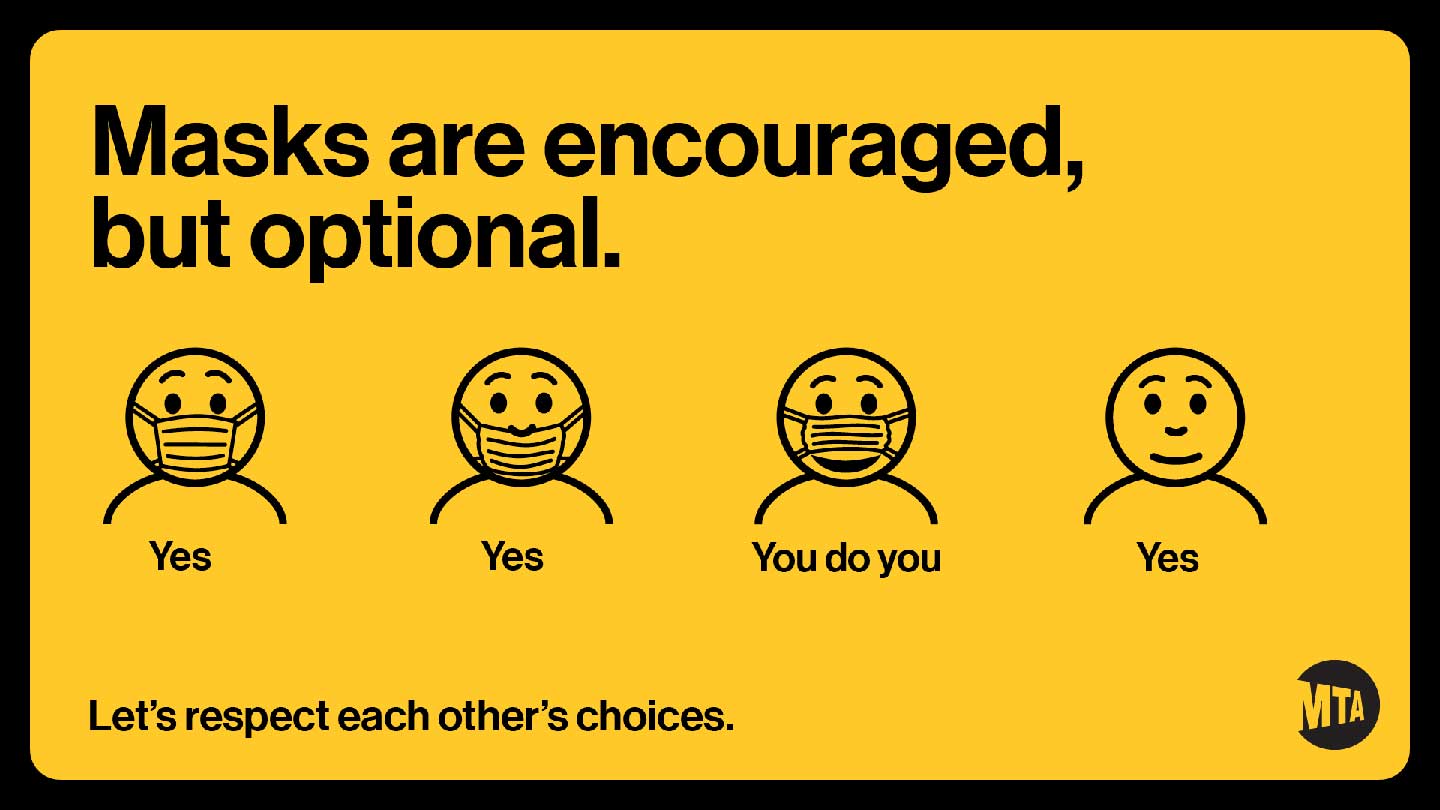

In the absence of federal standards and political leadership to implement them, many local leaders have simply defaulted to lowest-common-denominator policy-making, often with troubling consequences for those most at risk. “Protect the vulnerable” has been a common refrain in US Covid policy, but meaningful protection remains elusive. In an increasingly fragmented, personal-choice-centric policy landscape—what one writer has approvingly called the “you do you” approach to the pandemic, and which New York state has now made explicit in new posters announcing the end of public mask mandates—immunocompromised and other high-risk individuals are supposed to “choose” whether and how to protect themselves in public settings. Official guidelines have positioned non-pharmaceutical interventions, like masking and social distancing, “as an imperative for the vulnerable and a choice for everyone else”—an approach that directly weakens the effectiveness of those measures, as Maggie Mills recently wrote. Covid Coordinator Ashish Jha has argued that pharmaceuticals like Evusheld and Paxlovid are the best means of protecting vulnerable groups—but has also tended to gloss over the obstacles that prevent ready access to these treatments.

For the past year, the United States has tried to extinguish the pandemic one meager puff at a time—only to see it reignite like magic relighting candles. We’ve collectively surfed the short-term euphoria of calling the pandemic over, removing restrictions, and enjoying being “vaxxed, paxed, and relaxed”—and then repeatedly confronted new variants and surges. And yet the siren song of no-strings fun remains intoxicating: The White House is now touting the “soft closing” of the pandemic, even as it refuses to pick up the tab. But the party really is over—even if the promises of good times are not.