The Nation and Magnum Foundation are partnering on a visual chronicle of untold stories as the coronavirus continues to spread across the United States and the rest of the world—read more from The Invisible Front Line.—The Editors

Images have power. The strongest images have the ability to communicate a message that is more convincing, more believable than any written word. It was images—videos of young Black men being killed by police, by vigilantes—that has motivated so many people to take to the streets in protest these past few weeks. It has been images that are driving so many of the changes these protests are bringing about.

I’ve been making images most of my adult life, and have always been driven by a desire to document Black culture, my culture. I started photographing for my own personal purposes in the 1980s, but as time progressed, and when the crack and AIDS epidemic hit, the image of the Black man and woman in America started to shift, and I wasn’t happy with what I saw. I was seeing images that painted the spirit of addiction and mass incarceration, and I realized that I had a responsibility to provide a counternarrative. I believe in balance. I felt it was necessary for me to go out and document the love of family, the mothers and fathers, the children, the hope, and the promise. For me, it was a mission to do that. I was inspired by what W.E.B. Du Bois did in the Paris exposition of 1900—he brought images of Black life to the public, beyond the sensationalism. I wanted to focus on honor and dignity.

I started my career as a corrections officer at New York’s Rikers Island jail in the 1980s. Every day I went to work and looked in that pen to see who I could pull out, to see who I knew from the community. I always brought newspapers and extra magazines to encourage young men to read. I went to work looking for Malcolm; I went there looking for Mandela. I knew there were a lot of men who were incarcerated and didn’t need to be in there. I tried to guide as many young men as I could.

One of the ways I used my camera as a tool for Black liberation was by simply recognizing the inner beauty that my subjects possess. In photographing, I always tried to impart knowledge. All my work was really about just reaching the people—photography was secondary. The primary aim was to talk to people about what was going on in America and how we needed to wake up. The camera was the master key that allowed me entry into the hearts and minds of the men and women I photographed. We grew up with a mantra, and it stayed with me for many years, even to this very day: I want for my brothers what I want for myself. I went out there with that passion and a duty. The camera became a compass to help guide me.

I carried two things with me at all times: my camera and my chessboard. I started to teach a lot of young men chess, because chess to me was teaching the science of conflict resolution, decision-making, strategy, and patience. I would say: This is the game of life. If you understand this game—and beyond the physical game, if you understand how it’s related to life—it will carry you on through a lot of difficult times. Before you make a choice, you take time to look at your mental chessboard. You analyze it. You look at the sacrifices. You make hard decisions, and you make your move.

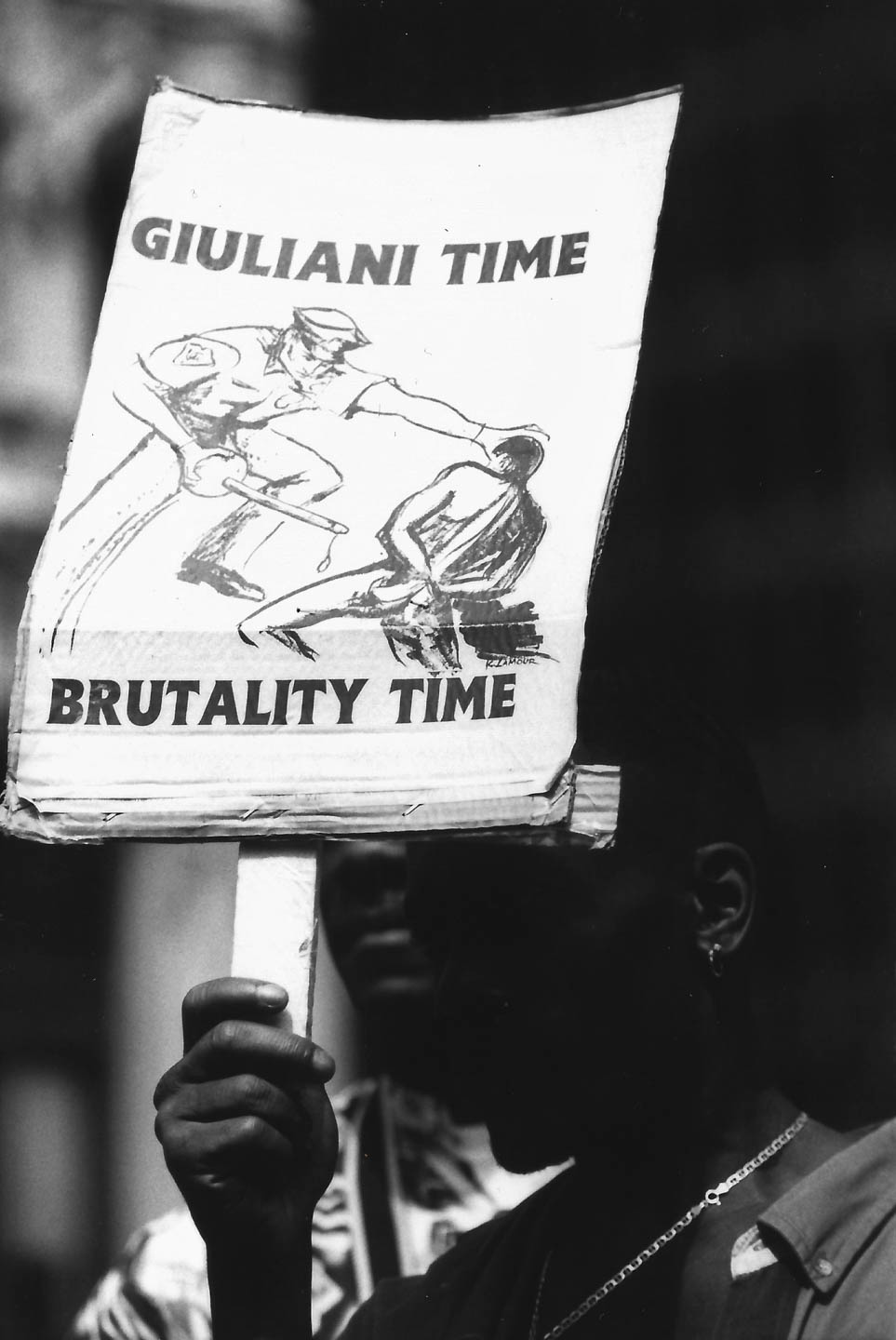

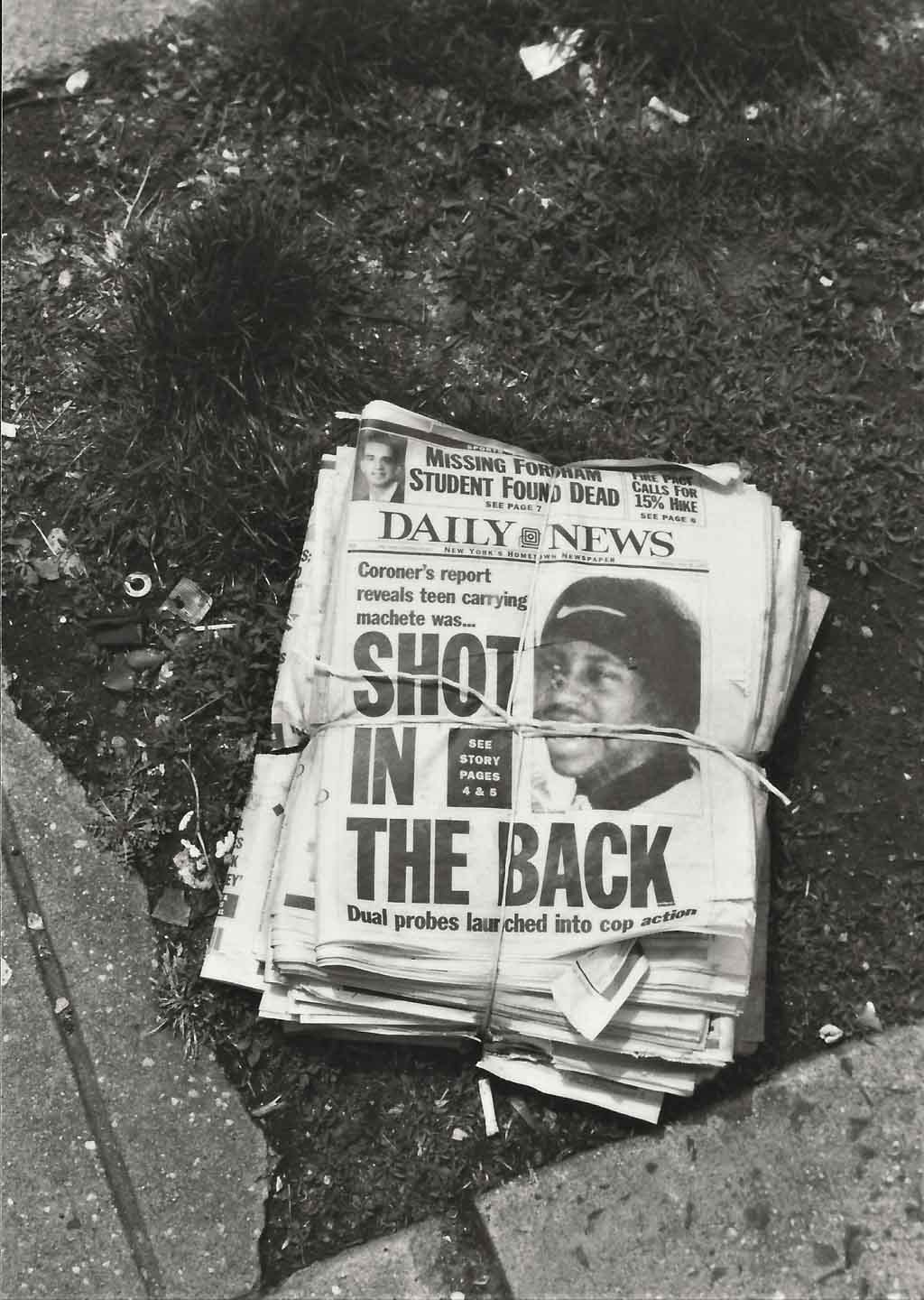

In the 1990s I began working at the 100 Center Street Supreme Court in Manhattan, in the heart of the city. Police brutality was at an all-time high, and protests filled the streets. Giuliani was the mayor. The Rodney King verdict, O.J. Simpson, all these major racial incidents affected me. As a Black man in America, I was always looked upon as a suspect, an enemy of the state. But in my job, I enforced the law. It was a kind of double consciousness. On my lunch breaks I would photograph, feeling a sense of freedom.

The 2000s provided me with a great opportunity to meet a number of up-and-coming visionaries and artists. That was the joy and one of the greatest blessings of my books’ being published. I had an opportunity to meet a lot of young people who look to me as a mentor for the type of work I’ve done. Elders like Gordon Parks and James Van Der Zee weren’t around, so I was someone in the flesh that had created something that served as a beacon to a lot of young people. I always wanted to be one that was open and available, approachable.

The coronavirus pandemic has changed so much about how we do things in terms of greeting each other, in the handshake, the hug. With that being gone now, I don’t know how that’s going to impact people on an emotional level, especially during a time of tremendous loss, when a hug serves as a form of reassurance, assurance. And now it’s gone. I’m not one to shoot from afar. Most of my photography is rooted in having conversations with people, and now there is an element of apprehension and fear in everyday connections. How are we going to grow as a society when everyone is wearing a mask, when we can no longer interact the way we once did?

Right now, we need all hands on deck to produce a counterbalance to all this negativity in hopes of making not only this country a better place, but the world a better place. We’ve shown our power in using our cameras to address police brutality. Let’s continue to use that same energy to address other issues, and prove that we are truly concerned about injustice at a global scale. We are living in some very troubling times when hatred and division are on the rise, but the youth are in the streets, struggling to bring about long-overdue change. In order to make a better world for our children and loved ones, we must come together as concerned citizens and use our individual platforms to spread messages of empathy and justice for all.