The Last Steep Ascent The Last Steep Ascent

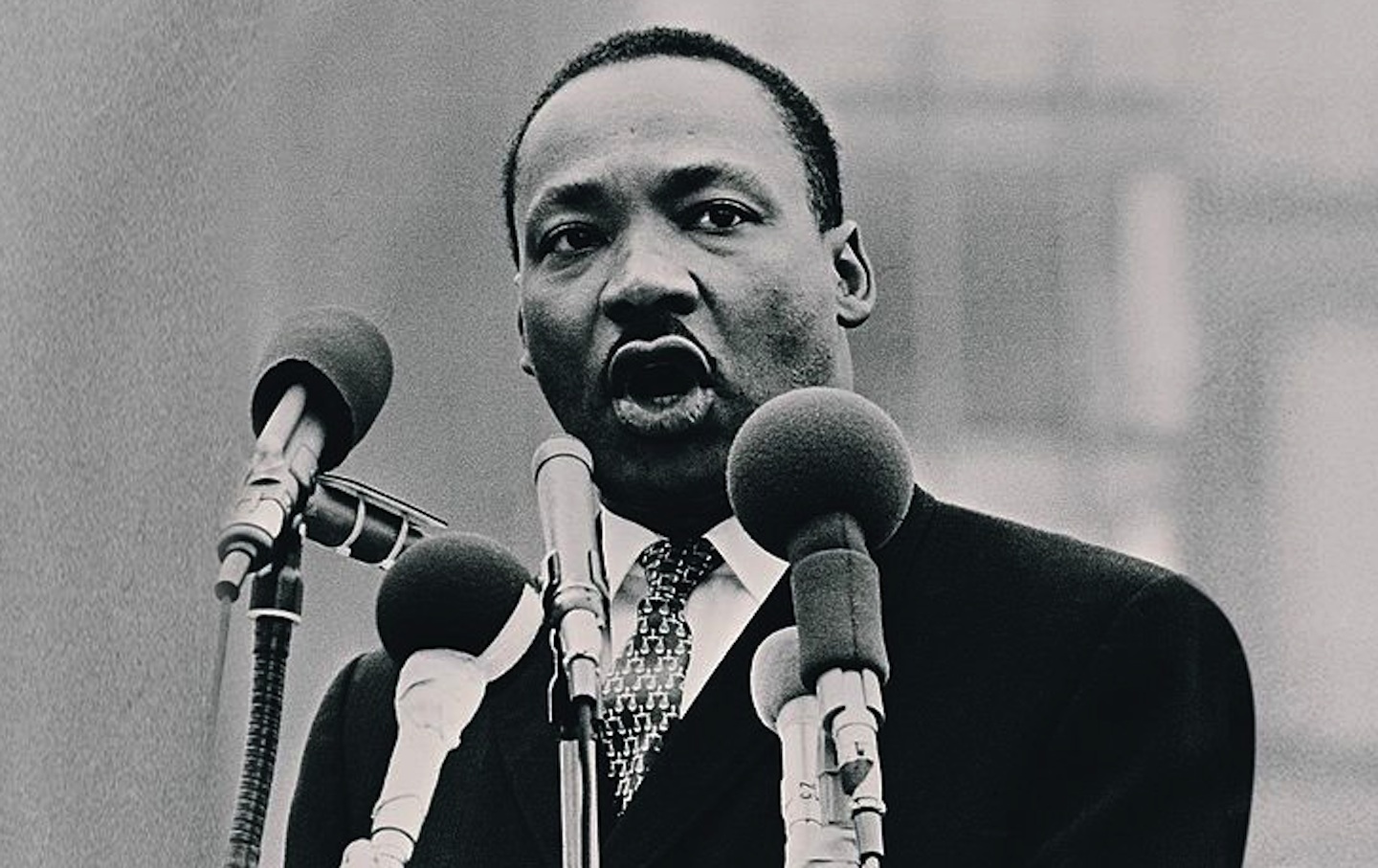

New obstacles should not be deplored but welcomed because their presence proves we are closer to the ultimate decision.

Mar 11, 1966 / Martin Luther King Jr.

LSD: ‘The Contact High’ LSD: ‘The Contact High’

Though LSD was first synthesized more thall twenty years ago, national illumination as to the effects of psychedelics did not occur until the Harvard scandal of 1962-63. University authorities objected to the "use" of undergraduates in experimeats begun in 1960 by Professors Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert. Forced to leave Cambridge, Leary and Alpert, with research fellow Ralph Metzner, began a hegira, first attempting to found psychedelic communities in Newton, Mass , then in Mexico, then on a Caribbean island, finally at the Castalia Foundation in Millbrook, NY, where Leary lives and works with a small group devoted to the exploration of the consciousness-expanding drugs. On the way, a great deal of straight-out evangelism has been generated for the experience in scores of lectures and discussions, as well as in a scholarly journal, The Psychedelic Review, and a book, The Psychedelic, Experience (University Books, 1964), which is a manual based on The Tibetan Book of the Dead (Further manuals—on scienstific, therapeutic and aesthetic models—are promised). Ihe double-edged promise of psychedelic exstasis—psychosis/enlightenment—is sufficiently fearsome to keep many potential voyagers from taking a trip. The danger of flipping out—permanently losing touch with reality—is quite real, although casualty rates on psychedelic experiences are hard to come by, and perhaps fewer than one in 10,000 experiences results in lasting mental damage. LSD has been used with varying degrees of success, in psychotherapy, as well as in the, training of psychiatrists ("this is what psychotics feel like..."), the treatment of alcoholics, and the reduction of anxiety in terminal cancer patients. Further, as Aldaus Huxley put it, today's "aspiring mystic" would be foolish to try self-flagellation and prolonged fasting. He should, Huxley advised, knowing "the chemical conditions of transcendental experience...turn for technical help to the specialists..." So far LSD, psilocybin, mescaline, et al., are legally available only to professional investigators, who have filed their research programs with the Food and Drug Administration (psychedelics, which are not addictive, do not come under narcotic codes), but the drugs are not hard to obtain from local connections. And now that marijuana, which is a mild psychedelic, is acknowledged kid stuff, the use of wonder drugs can be expected to increase dramatically. For all the talk. testimonials and debate, however, there have as yet been n o public sessions—after all, the drugs are illegal, and who wants gawkers anyway. But how to translate the experience into terms the uninitiated can understand by subjective reports? Scientific analyses? How-to lessons? Humble question-and-answer sessions? None of these stratagems do the job, since, ultimately, either you have or haven't taken a trip yourself. Luckily, art imitates life, and lectures-cum-demonstrations were introduced this spring at the Village Vanguard in New York. A series of Monday night sessions, opened June 14 at the New Theatre, 154 East 54th St. The lean, tanned, Giotto-saintlike Leary calmly announced on the first night that in the past six months the psychedelic revolution had been won. There are now available (1) the accounts of explorers, spokesmen and publicists, (2) manuals and maps for the trip; and (3) materials to go up on. "And tonight," Leary continued, "we are going to run a session for you. We are going to try to turn you on." But short of a real drug-dole, how, if the experience really is Something Else, can the ordinary audio-visual techniques produce a trip? The key to the possibility of a psychedelic theatre is the notion of the "contact high"—an experience attained solely by being with—tuning into—someone who is up on the drug. Further, it seems to be possible, even though chemical traces of LSD do not linger in the brain, to lapse into or recapture psychedelic intoxication long after the actual experience. William S . Burroughs, today's De Quincey, who attributes many scenes in Naked Lunch to psychedelics, tells of a Proustian reactivation of the experience when "the precise array of stimuli—music, pictures, odors, tastes" encountered during the experience are duplicated. "Anything that can be done chemically," says Burroughs, perhaps presaging a neo-neo-Freudianism, "can be done in other ways, given sufficient knowledge of the mechanisms involved." The psychedelic theatre attempts to stimulate multiple levels of consciousness by audio-visual bombardment. Its creators, a Woodstock, N.Y., trio publicly known as USCO, comprised of former Playboy correspondent and poet Gerd Stern, ex-Pop artist Steve Durkee, and electronic technician Michael Callahan, call the barrage of films, slides, kinetic sculpture, strobe lights, tapes and live actors a "multi-channel media mix." These fancy terms are partly a tribute to the University of Toronto's communications commentator Marshall McLuhan, who takes a prominent place in the philosophical background of the psychedelic theatre, supplying contemporary technical insights to balance the Oriental mystic of such figures as Meher Baba, who "in ancient times was called Jesus the Christ, Gotama the Buddha, Khrishna the Lover and Rama the King." McLuhan argues that media study should concentrate on the effects of the technology on the environment, on social organization and thought, not on the programmatic content the media transmit. "The medium is the message," says McLuhan, who recalls how the invention of movable type provided universal access to the word and led to secular learning, individualism, nationalism and the assembly line. These forms, for McLuhan, are based on the model of the line-of-type, which is linear, sequential and bi-dimensional. In the electronic age, however, the model is circuitry, which offers multiple, simultaneous connections, as in the analog computer, Telstar and world government. In other words, explains the USCO group, while the old-fashioned, single-screen movie with its sequential, frame-after-frame progression, worked once, we now need simultaneous, multiple images. More than that, we need a new theatre that will provide a total art, a grand combination of media. At the New Theatre the media are a half dozen film and slide projectors which wander and blend images over a huge screen which fdls the proscenium arch, two "analog projectors" which are forms of lumia or color-organs developed by Richard Aldcroft, four diffraction hexes which are boxes in which revoke hexagonal figures studded with diffraction gratings (they break up the light like a prism) two NO-NOW-OW boxos which flash those combinations of letters with much clicking, as in an electronic brain, one presentation oscilloscope the size of a TV set, a strobe light which danced behind the screen; several sound channels ranging from the Beatles to erotic breathing; as well as a live drummer and, for the opening moments of the session, sitting on mattresses amid the media, a live "voyager" and two "guides," one of whom would—if it were for real—go up, while the other remained down, to serve as ground control. Enumerating the equipment does not indicate its effect. The experience, like a real one, was ineffable: The oscilloscope gave out wave forms, the analog projectors oozed phantasmagorias, the film and slide projectors beamed out Buddhas, 'traffic signs, trampoline leaps in slow motion, rocket launchings, living cells, a woman's body. At (times you could look at everything all at once. At times nothing. Horror, boredom, ecstasy, mild amusement. Though for want of time, skill and money the presentation is amateurish, especially when compared with those masterpieces of multi-screen film at the Johnson's Wax and TBM World's Fair pavillions, the psychedelic theatre is tremendously ambitious, whether it turns you on or not. "One reason artists experiment with psychedelics," says Dr. Melvin Roman, sculptor and assistant professor at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, "involves the kinds of pressures society puts on the artist to do what the ordinary human being can't do. Many artists are panicky. They are searching for some perhaps magical way to remain in touch with themselves and still comply with the irrational demands of society." At the first of two discussions held recently at the Coda Gallery, currently showing an exhibit of psychedelic art, Dr Roman joined several other mind doctors to evaluate the ways an artist might profit or suffer from psychedelics. Many of the doctors had not had the experience themselves and may perhaps have been too easily tempted to dismiss it as a crutch or short cut, to reject the art as (simply) similar to that produced by psychotic patients in a mental hospital. But the next week at the Coda, the discussion involved the artists themselves. They insisted that art remains hard work, that during the experience itself they usually had no interest in painting, that the experience opened up whole new realms, led to totally new self-conceptions, gave much inspiration and material for work. One artist who found great pleasure in painting while high, said he also tried to incorporate into his work the pain of coming down or losing the effects of the experience. Another artist, dissenting from the general enthusiasm, said he was probably a better craftsman without psychedelics, inasmuch as the experience made him too anxious to make a statement. On the first program, Dr. Ralph Metzner of the Castalia Foundation, complained about the traditional Western concept of the artist as an individual engrossed in trying to express his own personality. According to Metzner, psychedelics might have the effect of renewing a more traditional view of artistic work, in which the artist remained anonymous, part of a group whose major effort was directed to turning on the viewer. At the New Theatre, Leary added another slant to the possibilities of psychedelics: "The problem in the past has been how to achieve release [from normal banality] but now, visionary experience is available to everybody. And the problem is how to come back, how to incorporate what you see on the trip into everyday life." So far the art produced as a result or under the influence of drugs may not seem of great importance. (The Burroughs of modern painting is Henri Michaux, who showed at the Cordier and Ekstrom Gallery this spring). But something new is happening, and it may be wise to suspend judgment for the moment. To ride with the Castalian rhetoric: "...the human race has come to the juncture where it must decide where to be content with the subjugation of the material world, or to strive after the conquest of the spiritual world, by subjugating selfish desires and transcending self-imposed limitations." Howard Junker is a documentary film maker who frequently contributes to film magazines.

Jul 5, 1965 / Howard Junker

Let Justice Roll Down Let Justice Roll Down

"Those who expected a cheap victory in a climate of complacency were shocked into reality by Selma."

Mar 15, 1965 / Books & the Arts / Martin Luther King Jr.

The Free Speech Movement The Free Speech Movement

When protester Jack Weinberg told a reporter, "Don't trust anyone over 30," the '60s youth movement was born.

Dec 21, 1964 / Feature / Gene Marine

Fannie Lou Hamer: Tired of Being Sick and Tired Fannie Lou Hamer: Tired of Being Sick and Tired

Speaking for every African-American living under the South's Jim Crow rules, Fannie Lou Hamer says she is sick and tired of being sick and tired.

Jun 1, 1964 / Feature / Jerry DeMuth

General Douglas MacArthur General Douglas MacArthur

A piece on thee ways in which the late General Douglas MacArthur impacted the lives of people around him.

Apr 20, 1964 / Roger Baldwin

Hammer of Civil Rights Hammer of Civil Rights

“Exactly one hundred years after Abraham Lincoln wrote the Emancipation Proclamation for them, Negroes wrote their own document of freedom in their own way.”

Mar 9, 1964 / From the Archive / Martin Luther King Jr.

A Bold Design for a New South A Bold Design for a New South

Tokenism was the inevitable outgrowth of the Administration’s design for dealing with discrimination.

Mar 30, 1963 / From the Archive / Martin Luther King Jr.

The Balance of Blame The Balance of Blame

The article focuses on a situation of criticality that prevailed between the two power blocs of the world as of June 1960 that might've lead to World War III. Both the Soviet bloc ...

Jun 18, 1960 / C. Wright Mills

Federal Narcotics Czar Federal Narcotics Czar

IN THE world of U.S. Commissioner of Narcotics H J Anslinger, the drug addict is an “immoral, vicious, social leper,” who cannot escape responsibility for his actions, who must feel the force of swift,impartial punishment. This world of Anslinger does not belong to him alone. Bequeathed to all of us, it vibrates with the consciousness of twentieth-century America. Anslinger, however, has been its guardian. As America's first and only Commissioner of Narcotics, he has spent much of hls lifetime insuring that society stamp its retribution in to the soul of the addict. In his thirty years as Commissioner (Anslinger is now sixty-seven), he has listened to a chorus of steady praise. Admirers have described him as “the greatest living authority on the world narcotics traffic,” a man who “deserves a medal of honor for his advanced thought,” “one of the greatest men that ever lived,”a public servant whose work “will insure his place in history with men such as Jenner, Pasteur, Semmelweiss, Walter Reed, Paul Ehrlich, and the host of other conquerers of scourges that have plagued the human race.” But some discordant notes, especially in recent years, have broken through this chorus. Critics—mostly social workers, doctors, lawyers and judges—have cried, often out of their frustration, that Anslinger is a despot, a terrifier of doctors, a bureaucrat single-handedly preventing medicine from ministering to the sick, aimless addict. These critical views reflect the philosophy expressed in The Nation in 1956 and 1957 by Alfred R. Lindesmith, Professor of Sociology at Indiana University. "The addict belongs in the hospital, not in the prison," Lindesmith wrote. "If we recognize that punishment cannot cure disease, if we want to take the profit out of the illicit traffic, we need to return the drug user to the care of the medical profession—the only profession equipped to deal with him." ("Traffic in Dope Medical Problem," April 21, 1956). Lindesmith said the country's stringent narcotic laws stem from “conceptions of justice and penology which can only be adequately described as medieval and sadistic." (“Dope: Congress Encourages the Traffic," March 16, 1957). Anslinger has replied to such critics with more scorn than argument. Confronted with a recent medical proposal to set up government clinics where doctors would treat addicts and, in some cases, allow them to continue their drug diet, the Commissioner announced: “The plan is so simple that only a simpleton could think it up.” When this plan began earning support from influential men within the American Bar Association, the Commissioner answered their loglc by telling a national radio audience. “Certainly the ABA should have hired a lawyer to read the laws and find out what it is all about.” Warming up to the debate in an issue of the FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, he added his clinching argument: “Following the line of thinking of the ‘clinic plan’ advocates to a logical conclusion, there would be no objection to the state setting aside a building where on the first floor there would be a bar for alcoholics, on the second floor licensed prostitution, with the third floor set aside for sexual deviates and, crowning them all, on the top floor a drug-dispening station for addicts." A PENNSYLVANIA Dutchman, Harry J Anslinger was born in Altoona on May 20, 1892. It was the era of unlimited traffic in narcotics. Cigarette smoking irritated public morals more than did opium eating (to shush their hahies, mothers bought 750,000 bottles of opium-laced syrup a year). Drug manufacturers mixed laudanum, heroin and cocaine into their tonics and pain-killers. “The more you drink," one tonic advertised, “the more you want.” The fashionable bought gold hypodermic needles, studded with diamonds. By 1914, when Anslinger was a student at Pennsylvania State College, the New York Sun estimated that 4.45 percent of the population was addicted to narcotics. “Cocaine and its allied intoxicants...,” the New York World said, “are seemingly cheaper than whiskey, cheaper than beer....” Time and again, reformers lashed out at doctors for dispensing drugs too freely, for eliminating diagnosis as well as pain in the single stab of a needle. The magazines of the period coupled concern for addiction with concern for alcoholism, and the same forces that created Prohibition devised the Harrison Act of 1914, which clamped federal controls on narcotics use and sale for the first time. DURING these years and the decade that followed, Anslinger’s activities hardly touched the narcotics problem. At the start of World War I, he joined the Efficiency Board of the War Department’s Ordnance Division and, by the close of the war, had advanced to the post of attaché in the American Legion at The Hague, Netherlands. He continued in foreign service until 1926, serving in consular posts at Hamburg, Germany; La Guaira, Venezuela; and Nassau,Bahamas. As Consul in Nassau, he negotiated an agreement with Britain to halt a fleet of rum-running schooners heading for the high seas. The agreement plugged one hole in the defense against Prohibition smuggling, and the federal government soon promoted Anslinger to Washington's chief of the Division of Foreign Control in the Prohibition Bureau of the Treasury Department. Three years later, in 1923, he rose to Assistant Commissioner of Prohibition. Three months later, in early 1930, a scandal rocked his bureau. In New York, a federal grand jury investigating narcotics, which then came under the jurisdiction of the Prohibition Bureau, accused narcotics agents of falsifying their reports on orders from superiors in Washington. The agents had padded their records by copying the New York police files. The padding, which amounted to 354 extra cases in 1929, had heen done on orders from William C. Blanchard, Assistant Deputy Commissioner of Prohibition in Charge of Narcotics, who claimed he had acted on orders from his superior, Col. L. G. Nutt,the Deputy Commissioner. The grand jury said it found strong indications of collusion between federal narcotics officials and illegal sellers. The padding obviously had been intended to hide the bureau’s poor record of arrests. The Prohibition Bureau quickly reorganized itself. Nutt was demoted to field supervisor. Assistant Commissioner Anslinger, unassociated with narcotics and free of scandal, assumed Nutt’s duties temporarily. Congress, however, decided that more than reorganization was needed and passed a bill transferring narcotics control from the Prohibition Bureau to a new Bureau of Narcotics in the Treasury Department. President Hoover signed the bill on June 14, 1930, and appointed Anslinger to the new position of Commissioner of Narcotics on August 12. BY THEN, federal policy in narcotics had been set. The courts had approved the Constitutionality of the Harrison Act, and bureaucrats, fired by Prohibition zeal,had plucked from the medical profession any responsibility for treatment of the addicts who had lost their legal source of supply. Narcotics had become a police problem, not a medical one, and Anslinger accepted the task of making sure it stayed that way. Working tirelessly under four Presidents, never wavering from his early mission, he has succeeded. In the United States, unlike almost every other Western nation narcotics remains a police problem. Throughout his tenure, Anslinger has proclaimed that “strong laws, good enforcement, stiff sentences and a proper hospitalization program” are the weapons needed to destroy narcotics addiction. On its surface, this program seems intelligent and compassionate; it implies that sick men must be treated and that evil men, who prey on the sick by selling them drugs, must be punished. But the Commissioner has a different concept in mind. He is less concerned with treating the addict than with removing the “leper” from society. In a recent article, he wrote: "It is essential...to remove the addict from circulation, either by a compulsory-treatment law or a law similar to that now in effect in the State of New Jersey.” He then described the New Jersey law,under which “any person who uses a narcotic drug for any purpose other than treatment of sickness or injury...is an addict and may be sentenced to a year in jai1.” In The Traffic in Narcotics (1953), a book he wrote with former U.S. Attorney William F. Tompkins of New Jersey, Anslinger cites with approval a recommendation that any addict committed to an institution three times under a compulsory-hospitalization plan should be incarcerated there for life. This proposal has received the Commissioner’s approval despite psychological evidence that a final cure for addiction is rarely obtained without several relapses. It is also clear that under Anslinger’s hospitalization program, treatment centers would be open only to addicts who had broken no laws other than those forbidding the use of drugs. The impoverished addict, who jimmied open cars and shops to steal enough to pay the fantastic prices for illegal drugs, would head for jail and the cruel, cold-turkey treatment. So would the miserable, addicted pusher, who sold capsules to other victims to support his own habit. ALTHOUGH many critics deplore Anslinger’s attitude toward the addict, few disparage his zealous efforts to wipe out the illegal traffic. One has described him as an honest, hard-working cop. In Who Live in Shadow (1959), a book written with Sara Harris, Chief Magistrate John M. Murtagh of New York takes time out from his attack on Anslinger to salute the Federal Bureau’s "vigorous fight against smugglers.” No matter how much they agitate for a change in government policy, critics do not want to return to the days when narcotics could be bought freely at the corner drugstore. Yet Anslinger’s police methods have disturbed some observers. Judge Dawd Bazelon of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, for exnmple, has attacked the Federal Bureau’s dependence on informers. “It is notorious,” he says in last year’s Anderson Jones decision, “that the narcotics informer is often himself involved in the narcotics traffic and is often paid for his information in cash, narcotics, immunity from prosecution, or lenient punishment.... Under such stimulation it is to be expected that the informer will not infrequently reach for shadowy leads, or even seek to incriminate the innocent.” In New York last March, U.S. District Judge Edward Weinfeld acquitted a defendant who had been enticed into addiction by an informer for the Bureau of Narcotics. The judge said the defendant’s participation in the crime “was a creation of the productivity of law-enforcement officers." Although the bureau has been untainted by any significant scandal in its thirty-year history, Assistant U.S. Attorney Thomas A. Wadden, Jr., discovered in 1952 that a janitor had been stealing cocaine and marijuana from the Treasury Department’s narcotics stocks and supplying them to peddlers in Washington. Anslinger reacted, according to Wadden, by obstructing the investigation. “While we were preparing our indictments," Wadden wrote in a Saturday Evening Post article, “Commissioner Anslinger made pub1ic statements which tended to disparage our claims.... The bureau could see no reason for all the fuss.” Wadden attempted to link the janitor with some of the big traffickers in the capital, but, according to the prosecutor, Anslinger, accompanied by the press,personally led a siren screeching raid that netted a host of small operators and upset Wadden’s plans. The former Assistant U.S. Attorney wrote that he then dismissed pending indictments against three important operators, and an angry grand jury issued a report accusing the Bureau of Narcotics of negligence in the case. Nevertheless, Anslinger's record as a law-enforcement officer may be far from a poor one. He has carried out the federal narcotics laws as honestly and effectively as possible, with no more scandal or disregard for rights than some of the country’s best police forces have shown. But he has not been content with being an honest, hard-working cop. He has assumed the responsibility for influencing laws and policies as well as enforcing them. And, in this area, his methods have evoked severe and sometimes bitter criticism. TO PROVE that stiff laws hold down addiction,the Commissioner has grown fond of displaying charts and statistics. His most frequently quoted statistic puts the total number of addicts in the United States at 60,000, perhaps 50,000. He bases this figure on the specific number of addicts reported to the bureau by police agencies throughout the country. As of Dec 31, 1958, they had reported 46,266 addicts. He brushes aside any contention that many addicts have evaded the police. “Within two years,”he said on NBC’s Monitor radio show last July, “every addict, rich or poor, comes to our attention.” Yet in 1954, a Citizen's Advisory Committee reported to the California General Attorney that there were 20,000 illegal addicts in California alone. At that time, the bureau had enumerated 893 addicts in California; its latest tabulation for the state stands at 6,214. Anslinger’s pet statistics involve the situation in Ohio. In his annual report for 1958, he prepared a chart entitled, “Results of Effective Legislation on Drug Addiction in Ohio.” The chart, noting that the state had adopted its stiff narcotics law in September, 1955, employs graphic bars to show that although Ohio reported more than 300 new addicts in both 1954 and 1955, it reported fewer than one hundred in each of the three following years. In 1958, only thirty-eight were reported. “Continued enforcement of the twenty-three year minimum penalty for unlawful sale of narcotics provided in the narcotics law adopted by the Legislature of Ohio in 1955 has virtually eliminated the illicit narcotics traffic in that state,” his report notes. But another factor may have contributed to the dramatic drop in reported addiction heavy penalties often discourage juries from convicting defendants. A survey of Missouri’s experience sheds some light on the meaning of Ohio’s statistics. In recent years, Anslinger has been offering Missouri’s statistics as further proof that long jail sentences do the job. In his 1958 report, he cites the “salutary effects” of heavy penalties and strict enforcement in that state. The House Appropriations Committee received a pictorial chart from him last year showing a giant human figure depicting the state’s new addicts in 1956 and a dwarfish one depicting new addicts in 1958. Missouri itself, however, was not impressed. The legislature changed the state law a few months after Anslinger had handed the chart to the committee. The new law reduced the penalties for first conviction of possession of narcotics from a minimum two-year term with no probation to a maximum one-year term with probation permitted. “We found that juries simply would not send a man up for two years on the strength of a marijuana cigarette found in his possession,” Circuit Attorney Thomas F. Eagleton of St. Louis explained. "It was also felt that a minor narcotics offender, convicted for the first time, was as much entitled to ask for probation as a first-time burglar.” After this scrambling of his neat statistics, Anslinger retaliatedby cutting his force in Missouri from seven to three men.“Apparently they feel they haven’t got a problem,” Anslinger’s assistant, Henry Giordano, said of the legislators. “We do have problems elsewhere and need men, so we’re moving them.” THE Missouri incident marked the rare occasion when an agency of any government has questioned the authority or wisdom of Anslinger. Congress rarely questions either. While testifying on Capitol Hill, as he often does, the Commissioner has a persuasive manner. A stocky, completely bald man with a kind and gentle face, he speaks smoothly and reasonably. In 1956, the reports of the House Subcommittee on Narcotics and the Senate Judiciary Committee leaned heavily on his philosophy. So did the report of the President’s Interdepartmental Committee on Narcotics that year. The results were new federal laws do stringent that they set a two-to-ten-year sentence for persons convicted of possessing narcotics for the first time, refused to allow suspended sentences and probation in many cases, and permitted the death penalty for any adult, addicted or not, who sold narcotics to anyone under eighteen. While guiding Congress to one point of view, Anslinger also has helped generate an atmosphere which inhibits objective thinking on the subject. In 1958, the Joint Committee of the American Bar Association and the American Medical Association on Narcotic Drugs, impressed with how little is known about the addict and how little is done to cure him, issued a report that called for more research. In its most controversial section, the report suggested “that the possibilities of trying some such out-patient facility [where doctors would treat addicts and, in some cases, administer drugs to them] on a controlled experimental basis, should be explored.” The committee hoped such a clinic would cut down crime by providing a legal source of drugs to addicts under treatment. Anslinger quickly organized his own Advisory Committee, which issued a 186-page report on the ABA-AMA report. A remarkable document, cluttered with capital letters, boldface type, italics and exclamation marks,the Advisory Committee report uses every argument conceivable, even when they are contradictory, to belittle the ABA-AMA report. It is filled with repetitions, misquotations and scorn, and resembles a screech more than an argument. On several issues, Anslinger’s group makes intelligent, critical points, but these are made so loudly they are hard to hear. The whole tenor of the document indicates Anslinger does not want to win the discussion as much as he wants to eliminate it. This atmosphere apparently has persuaded the ABA-AMA committee to mark time and wait for Anslinger’s retirement before trying to have its recommendations accepted either by their parent organization or by the federal government. Other critics of federal policy also believe that the retirement of Anslinger will herald a new era in government attitude toward addicts. "There is only one way to start reform, "Chief Magistrate Murtagh writes, "—retire Commissioner Anslinger and replace him with a distinguished public-health administrator of vision and perception and, above all, heart." Will his retirement mean a new era? Anslinger has not been a single force legislating and enforcing narcotics laws all by himself. He has reflected an imbedded American distaste toward people who have grown ill because of a seeming lack of will, and he has struck a responsive chord within both Congress and the public. Although persuasive and hard-working, he could never have pushed through his policies if they had not conformed with the public disposition. When he retires, it may be that a man of different attitudes and philosophy will take his place. But his successor also may be another Anslinger. After thirty years in office, there is enough public reverence for Anslinger to carry his philosophy, and all it represents, beyond his retirement.

Feb 20, 1960 / Stanley Meisler