How to Visualize the Climate Crisis

A new immersive photography and video exhibition elucidates both the causes and consequences of the climate crisis, while also sparking creative solutions.

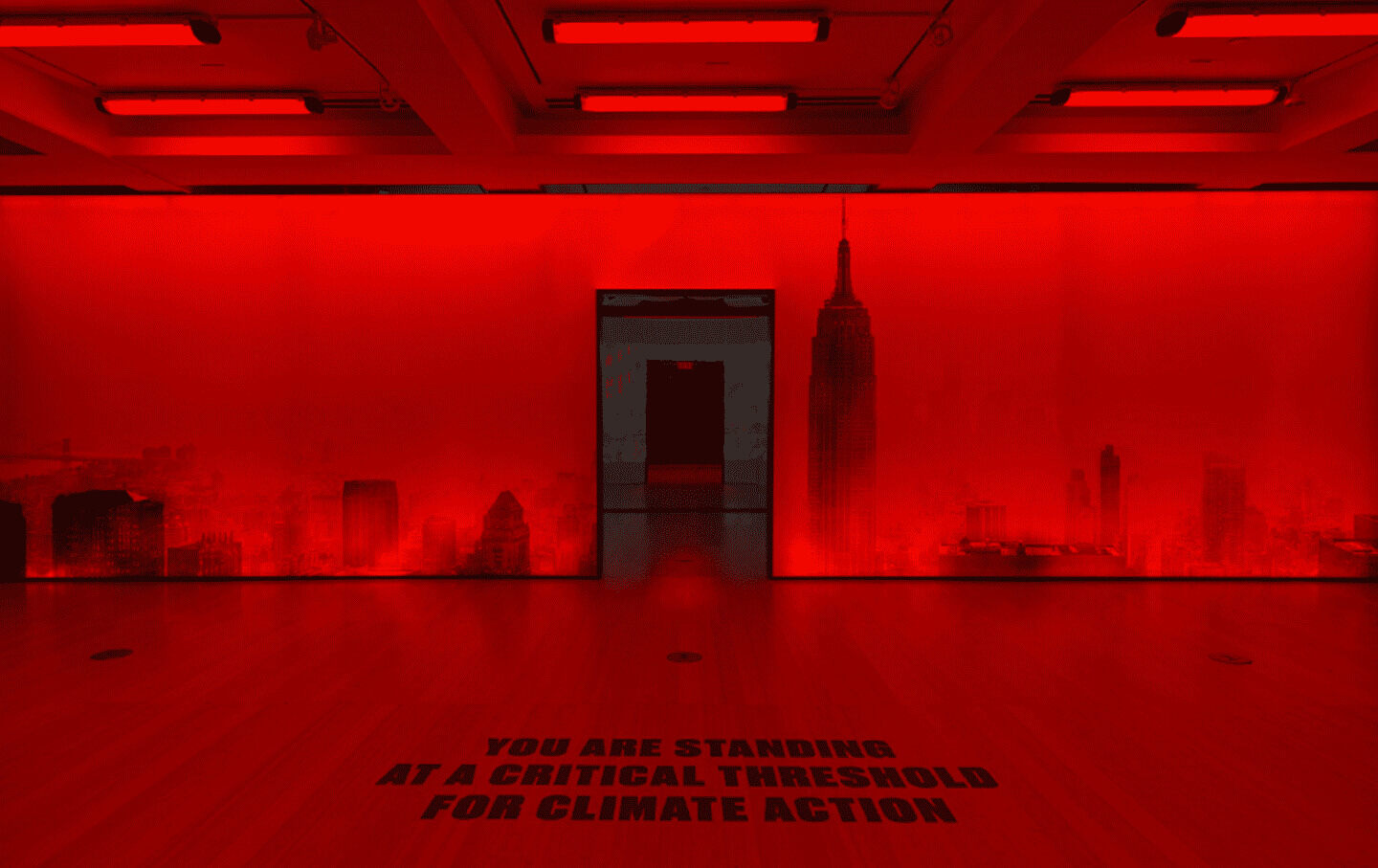

“You are standing at a critical threshold for climate action,” reads large text on the third floor of New York City’s Asia Society Museum. It’s just one of many immersive moments stopping visitors in their tracks at “Coal + Ice,” a new photo and video exhibition from Asia Society, cocurated by Susan Meiselas and Jeroen de Vries and based on research by Orville Schell. The exhibit’s goal is to expose the public to the impending reality of climate change and the importance of collaborating on solutions before time runs out.

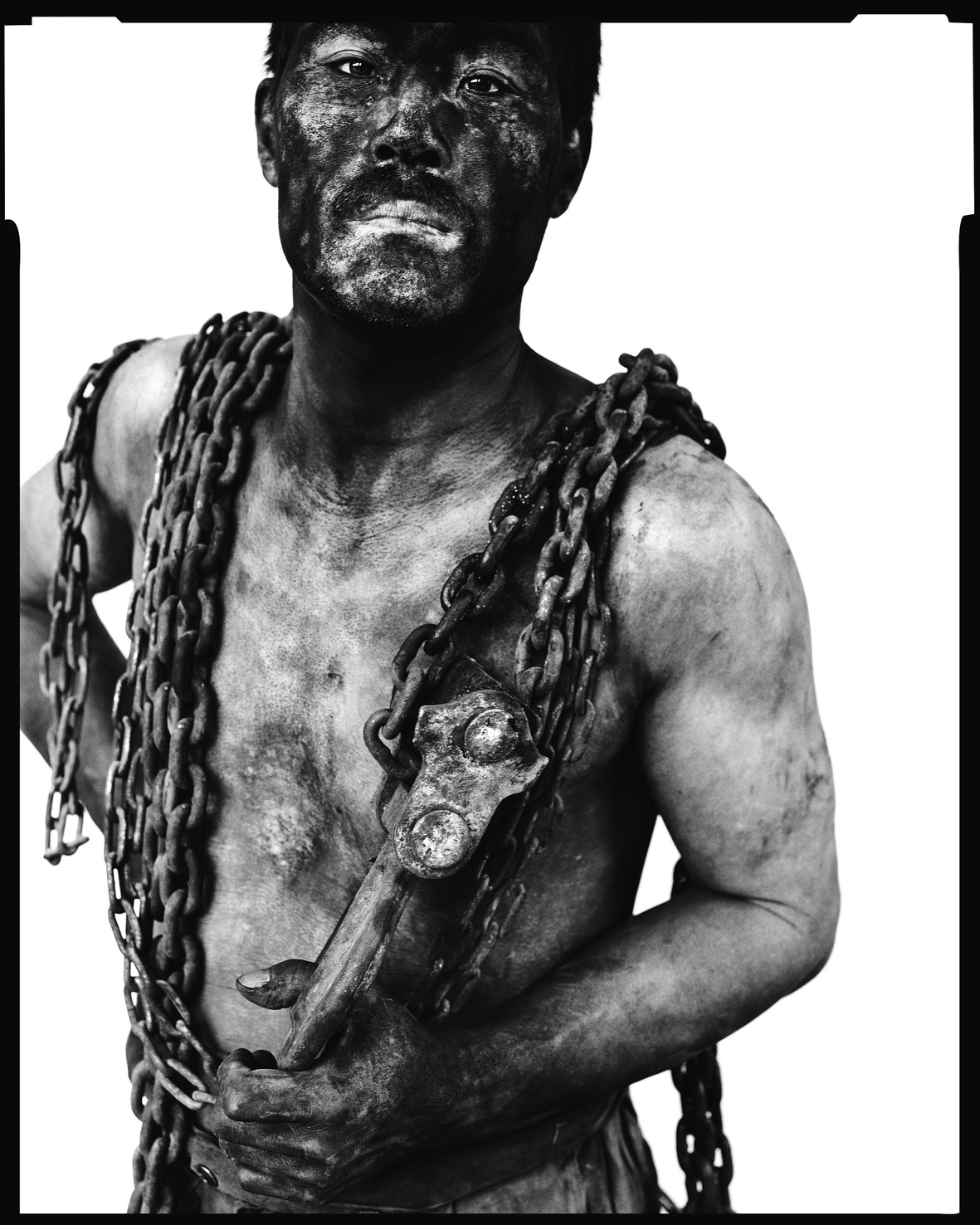

From a bright red room with the aforementioned text that features pictures of a New York City aflame, to haunting portraits of coal miners covered in soot, the interactive exhibit reminds viewers that climate change is not something to be underestimated. The Nation spoke with Meiselas and Schell about how and why the exhibition came to be. “Coal + Ice” is on display now in New York City until August 11, 2024.

The Nation: A central theme of this exhibition is collaboration, as each artist included in the exhibition is part of a larger story. How is collaboration essential to the mission of the exhibit?

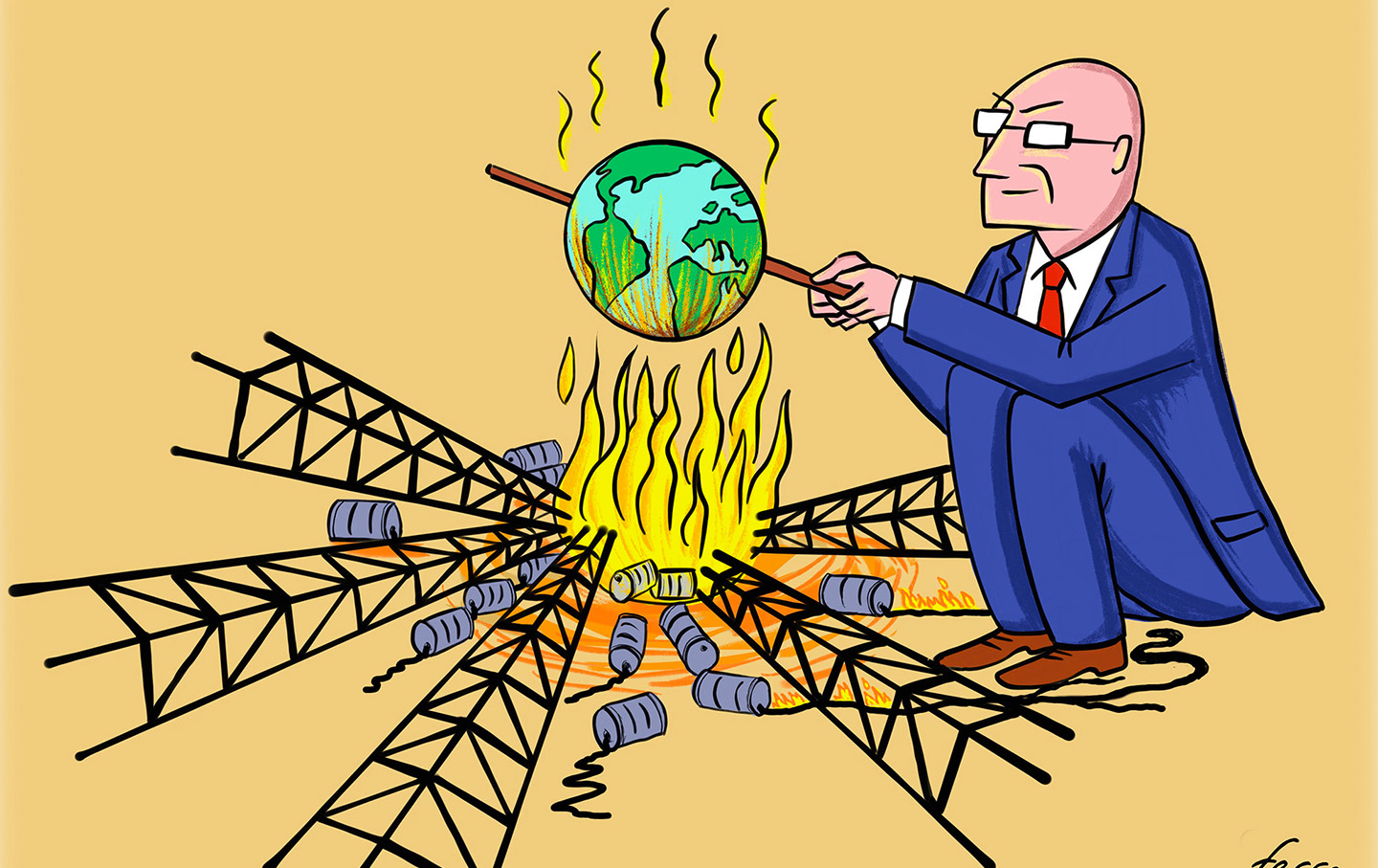

Susan Meiselas: It’s both video photography and a few other pieces. We’ve been doing this a long time, and it’s evolved. We feel that people aren’t listening to the climate challenge verbally and through newspapers and standard media. So we wanted to repurpose things like photography, video, art and music to bring them on board to try to wake people up in a slightly different manner. So the exhibit is a visual representation of that.

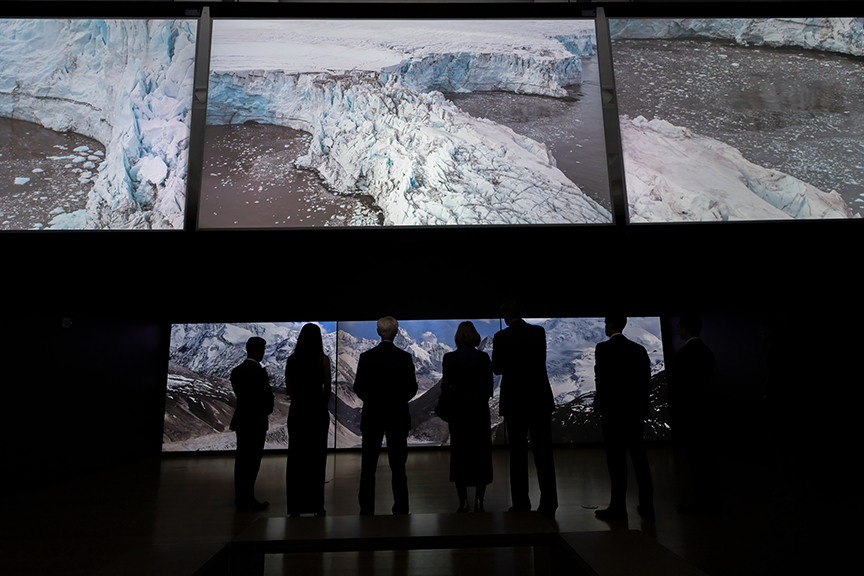

I think the strategy of the show is to create an immersive environment, one that makes you feel like you are in it. And you see that in parts of the exhibition more expressively, but essentially, there’s a historic dimension. And there’s a very contemporary body of work. There’s a lot of collaboration behind the scenes to bring this show together.

TN: The exhibit featured a poster-making section, where audience members are encouraged to create their own poster about climate change. Was the intention to create an immersive experience for the audience?

SM: It’s both an invitation and it’s hoping to be inspirational and inclusive. This show has had various iterations which began in China, and when it moved to Fort Mason [in San Francisco], it really expanded. The visualization became much more focused on digital projections, as it was in a 50,000 square-foot space in Fort Mason. So it had a drama to it. And then it was in a tent next to the Kennedy Center in DC, when it moved to the Asia Society.

I think there’s a very important idea that shifted when we moved from Beijing to San Francisco, which Orville had a vision for. Normally, in most museums, you have the exhibition space above, and you have an auditorium below and people sometimes do programming. What we did at Fort Mason was bring in the forum of conversations and dialogues from scientists, artists, entrepreneurs, musicians and different generations right into the middle of the show. And that was also done in DC. So when we talk about immersion, we were talking with the people and experiencing the world of climate change surrounding us. They weren’t abstract conversations. It was haunting, how powerful some of those intersections were. The next level of inclusion was to invite people to give their messages about how they understood climate change via a mobile app that then could be visible in the exhibition. It was projected that every time they used a photograph and sent a message, it was visible in the DC show and then in this show as well. So there’s a mobile app that is very easy to use.

Orville Schell: I think it’s a little strange for us to be wandering into this territory. Susan’s a photographer, and I’m a China guy. But I think we all feel that the two biggest challenges in the world today are climate change and China. And here they intersect with an incredible crash. And we figured that nothing else seems to work. So why don’t we mobilize across the board, get Alice Waters to do a climate friendly dinner, get Peter Sellers to repurpose Bach for climate change, cooperate with the San Francisco Symphony and Michael Tilson Thomas, and then with the National Symphony in Washington—let’s just get all aspects of life to mobilize themselves. We even got YoYo Ma to play Bach’s cantata Wachet Auf [“Sleepers Awake”]. And that’s basically what we want to do is find some goddamn way to wake people up.

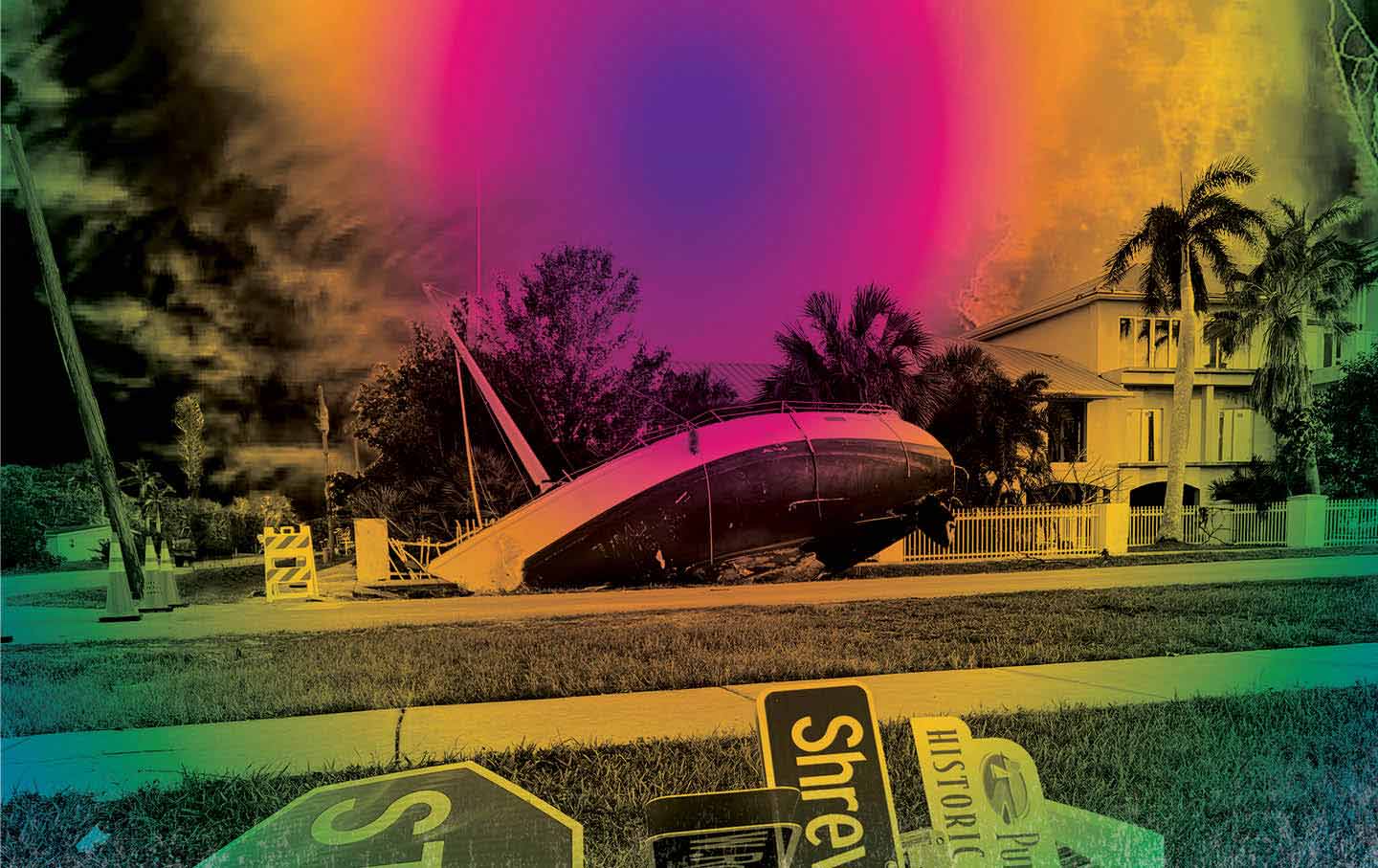

SM: It’s interesting. I’m not sure they’re not awake, but I do feel they are in denial still. Here we are suffering the heat. I was just in Europe, and people are shocked that a month earlier than normal, summer is hitting everywhere at extreme temperatures. One of the things that’s interesting about having multiple iterations over time is that the show keeps expanding beyond what we imagined. When we opened in Beijing, we didn’t have fires. We weren’t focused on global fires. We didn’t have any flooding. And what’s interesting is by the time we got to Fort Mason and it was around the time of the global summit, suddenly Paradise, California, went up in flames just as we were opening the show. So because it was digital projections, we could incorporate new work. It’s a very flexible model. And that’s also unusual; most museum shows are framed and pinned to the walls and our exhibit had the ability to respond to the growing and shifting conditions.

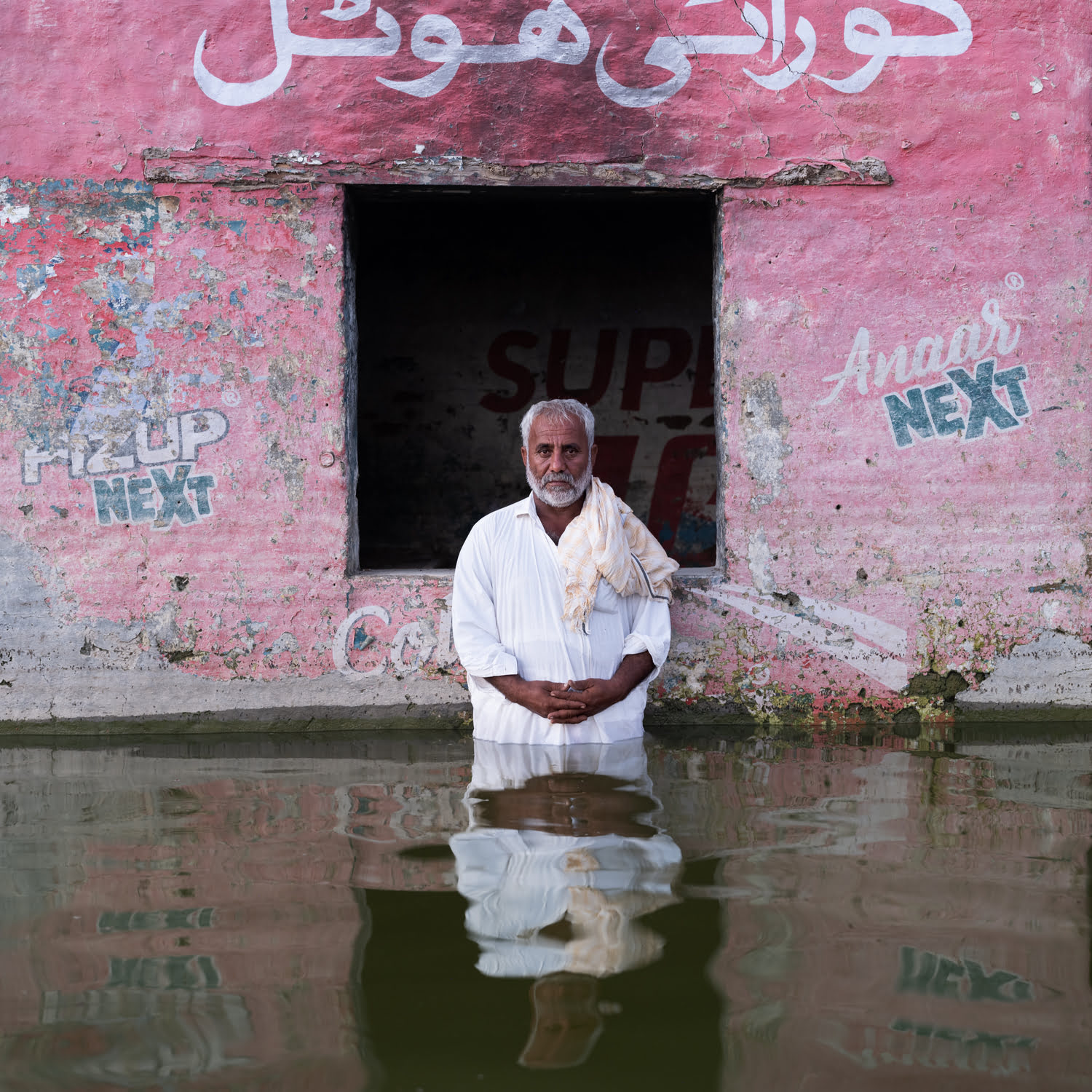

And again, we did that when it went to DC. So for example, the flooding series by Gideon Mendell has grown from including Bangladesh, where the photographs were taken, to progressively including the UK and US and so on. So he continues to document flooding in world’s capitals. And again, I think it’s one of the rooms that probably impacts people the most, because it’s small, it’s intense.

TN: I noticed the exhibit was structured in a cause and effect way, with coal miners on one side and mass environmental destruction on the other. Was the decision to create this divide between the coal miners and industrialization intentional?

OS: I think we wanted to do the narrative of climate change from coal standing in for fossil fuels of all kinds to the problem, then to go on to do consequences. And then to do solutions. So we thought, let’s tell the whole narrative here.

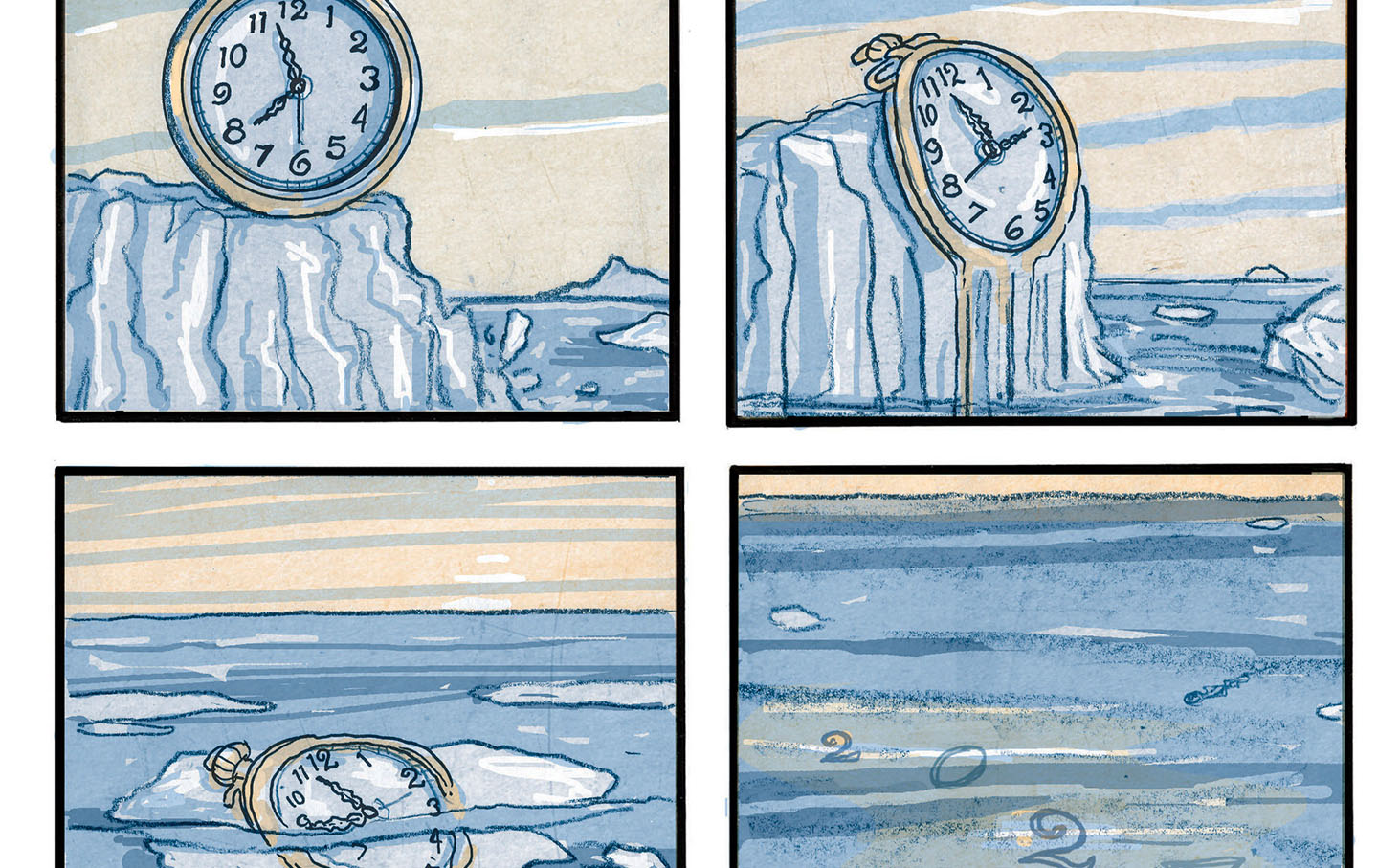

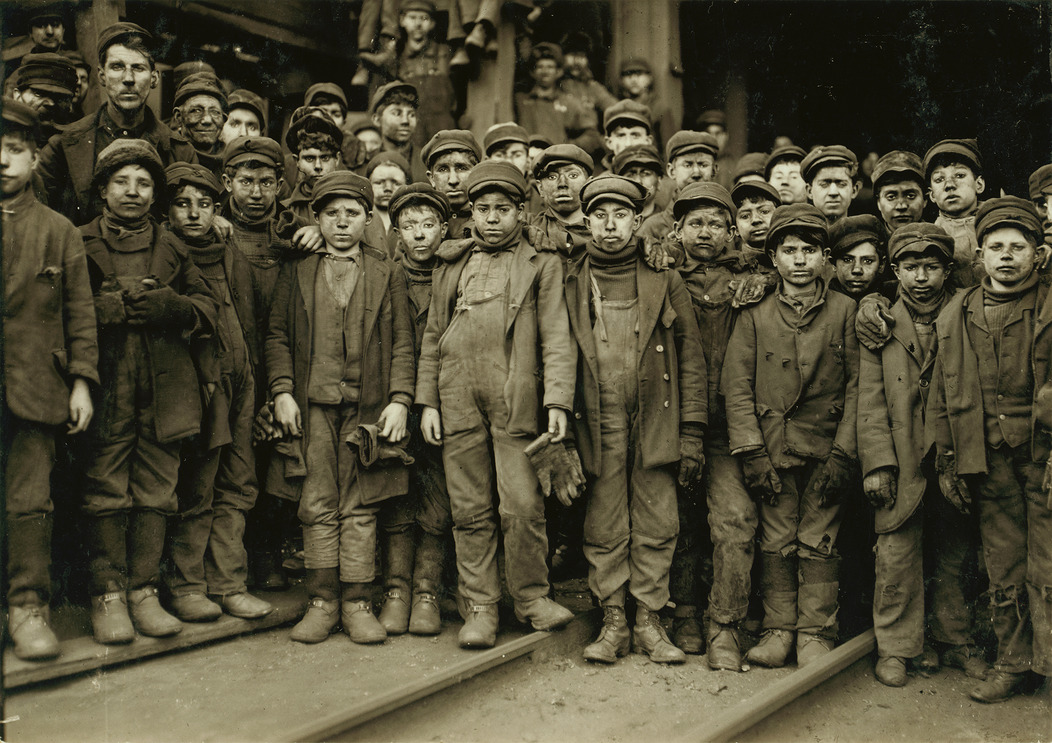

SM: On the second floor, you look to the left, and you see historic coal production, both in China where we did the original research, and Wales and Germany, where we took material from various parts of Western culture and industrialization, as well as the more recent material to make it very clear that this is ongoing at scale. You had strip mining, you had the results of mining in these big slag heaps. So everything on the left side of the gallery, when you first walk in, was just the different time layers around CO2 production. Then when you shifted over to the right, you would feel the polar ice breaking and the glacier melt. That is beautifully documented by David Breashears going back to the 1921 glass plate negatives. They point to exactly where and how much of a glacier melts and what the melt level is 100 plus years later as a consequence of migration, fire, and flooding. You have documentation by many means. So you have some film and video clips embedded, but you also have photographs that are made in black and white, you have color, glass plate negatives, and you have iPhones. You have citizen journalists just documenting what’s happening in their own homes and in their subways, along with professional photographers and mountain climbers such as David Breashears. So it’s a full range of recording this process that we’re all experiencing.

But when we first went to China together, we came back for Photo Fest in Houston and we did a show called “Mined in China.” And it was all focused on the various scales of mining and coal production. And it was through the connection with David that we then expanded the show to be called “Coal + Ice.” It’s a riddle. And I think Orville saw that there was an arch of connection. And we could build off of that. So then the research expanded and went into [the subject of] Western industrialization. So a lot of this research has been done on the Internet. And I think it’s an important detail to emphasize that our strategy, Jeroen and I, was to look for bodies of work. So we were not looking for stock photography. We wanted people who had committed to working in a particular way and in a specific place at a particular time. So you see series of photographs, not singular photographs for the drama of them. And that was very important to us; it’s all very highly authored work. We’re emphasizing the commitment of many people, including when you get to solutions. To me, it’s very important to see the work of Jamey Stillings, who has been documenting wind and solar farms around the world, which are extraordinary investments that most people never see. Essentially the scale of what is being produced in terms of alternative energy. So that’s the most positive solution we really can showcase.

TN: Explain the shift from coal mining as a symbol of human progress to a form of exploitative labor. How did that process start?

OS: Back in the day, workers were just workers. And that was their fate. And then labor unions came along. They just lionized them as the workers and they didn’t want the workers once they came to power rising up against them. The way they expected them to do in England and Germany and elsewhere. But we come to look at workers very differently. We’ve come to look at coal very differently because we’ve come to look at everything very differently. And we’re in a new world we’re at we’re past an inflection point, coal used to be looked at as the heart and soul of Britain’s power as an empire in the Industrial Revolution. Nobody thought another thing about it.

SM: One of the forums that we generated was around the idea of climate jobs, which is a union movement to reorient and re-educate and redeploy workers who’ve been in the coal industry into new alternative and green opportunities. And so they made a presentation. That’s a huge initiative that we wanted to showcase. So I think this question of it’s not about who’s going to vote for whom. It’s more so like, what’s our future going to be? What are the possibilities? What can happen?

The Nation: What is your response to people who say that China plays a larger role in climate change than the US does?

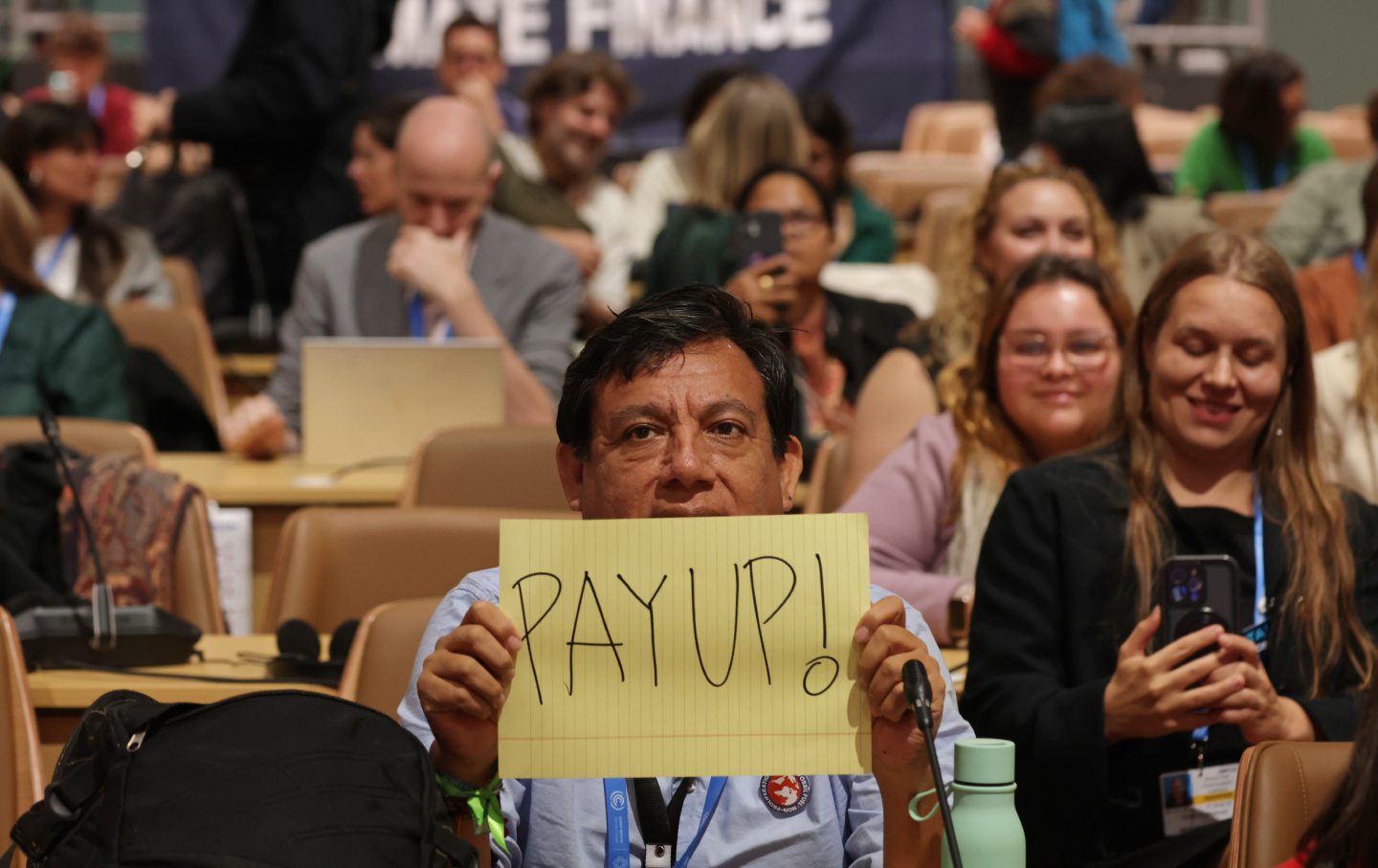

OS: I would say the US is the largest historical polluter, and the largest per capita polluter today, but China is the largest aggregate polluter. The point is, we’re all sinful here. There’s no one without fault. Not only are we all at fault, we’re all suffering together. And that’s the message of the show. We all have done this. And we all have to get together to get ourselves out.

TN: What are the main takeaways you’d like visitors to get from the show?

OS: I think we have different thoughts. I am a guy who lives in perpetual gloom. So I want people to take away that you’re destroying the planet. To other people who want to say let’s put a little hope into this, we put a gallery of solutions into it. It’s so different people will view this thing in different ways in terms of what should its message be. But I know one of the messages is blinking red light, danger ahead.

SM: I think the only other thing to add is, we wanted people to feel the intersectionality of the exhibit. The ways in which all these things intersect is really, really important. And I think when people read headlines they know about fires, they know about floods here or there. They don’t feel the impact of the whole thing. So even if you watch that map of the movement of the air around the world, people think that it’s there’s only air where they are standing. And these systems and the way they interact is what we want people to not just think about, but start to experience and imagine. Can it be different? Is it too late? I mean, these are really crucial questions for the next generation. What can individuals do? What can we do collectively? It’s both sides of that.

TN: What is the audience for this exhibit? Is it mainly geared towards individuals or corporations? And what should they do to help mitigate their impacts on the environment?

OS: Well, they all know what they should do. We all know what we should all do. And no, we aren’t doing it. It’s that simple. And some people are doing a little more than others. The point is, the world is so disorganized, and so fractured right now with other conflicts, that we’re distracted from the biggest challenge of all, which is the disruption of the operating system of the planet. So we have Gaza, we’ve got the Ukraine, we got Biden and Trump. Thomas Merton said, “You can’t judge an effort by its results.” And I feel very much that way. I have no idea if this is worth doing. But we did it. Because we gotta do something. And I don’t know what the right answer is.

SM: We’ve had very different kinds of responses from groups and individuals in the way they flow through the exhibit. But what’s interesting is to see the groups, whether it’s students, bankers, or NGO groups or people already committed to the climate issue. So there’s a whole range of different kinds of people. We’re trying to reach different sectors, even though it’s 70th and Park Avenue, which has its own bias. And so I think one of the things we’ve done with forums and invitations to groups is trying to open up that experience to a broader public by making [the exhibit] free on Fridays.