Wisner’s Ghosts

The making of a Cold War spy.

The Making of a Cold War Spy

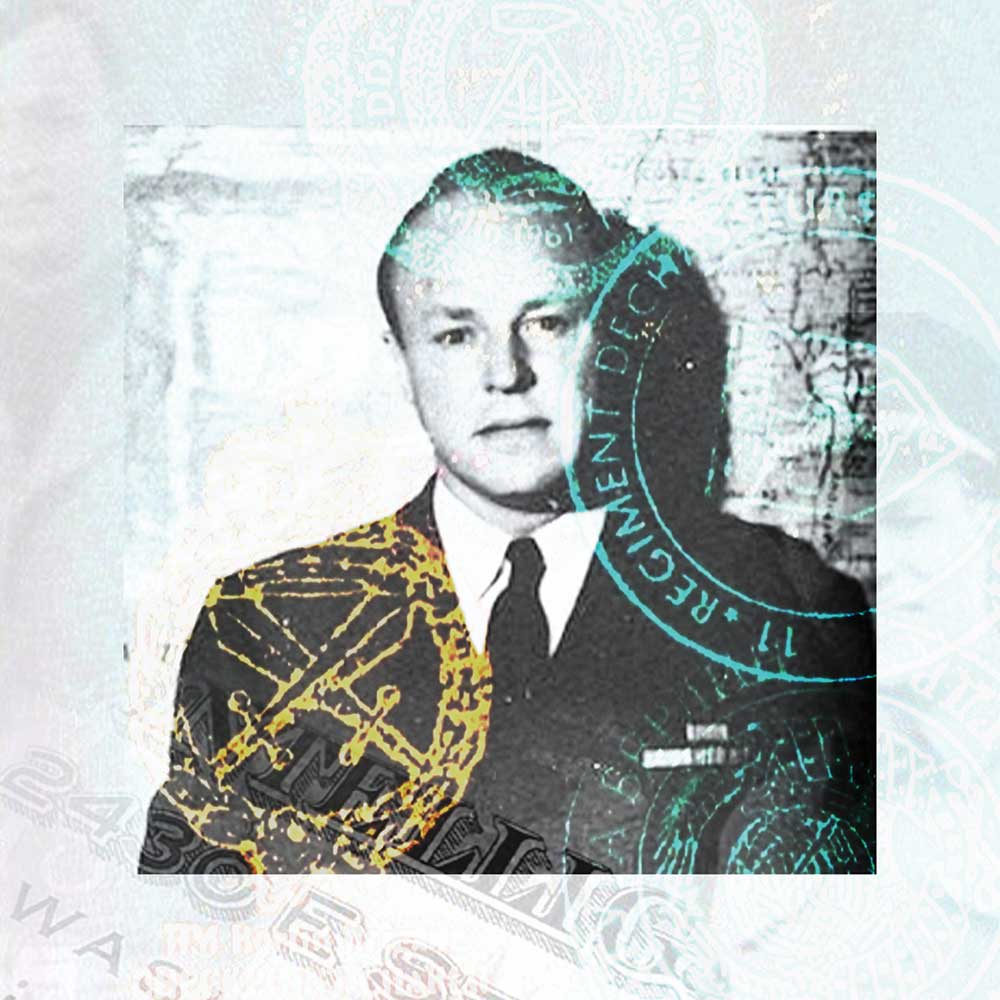

The life and work of Frank Wisner, one of the CIA’s founding officers, offers us a portrait of American intelligence’s excesses.

Sometimes it can be mostly harmless when the powerful lose their minds. For no discernible purpose, the Roman emperor Caligula ordered a floating bridge of ships stretched across the Bay of Naples and reportedly planned to appoint his horse as consul. King George III of England issued orders to people who were dead, shook hands with an oak tree, and believed he could see Germany through a telescope. He planted beef in his garden, it was said, in hopes of growing a herd of cattle. He had to be tied to his bed at night and put in a straitjacket by day.

Books in review

The Determined Spy: The Turbulent Life and Times of CIA Pioneer Frank Wisner

Buy this bookIn the nuclear age, however, madness can be dangerous. One man who had influence over such weapons was President Harry Truman’s secretary of defense, James Forrestal. Convinced that he was being pursued by a mix of White House officials, Zionists, and communists, he told friends, “They’re after me.” When a fire engine’s siren sounded, Forrestal rushed out of his house screaming, “The Russians are attacking!” He was eased out of his job in 1949 and, several months later, jumped out of a hospital window to his death.

Frank Wisner, a longtime CIA official, suffered in his later years from what we now call bipolar disorder and, like Forrestal, would take his own life. But it is remarkable how much he did to destabilize the world before showing any symptoms at all. As the CIA’s chief of clandestine operations, Wisner helped orchestrate the overthrow of Iran’s democratically elected prime minister, Mohammad Mosaddegh, in 1953, leaving power in the hands of the shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. The shah’s increasingly harsh authoritarian rule eventually provoked a massive popular uprising against his regime and its American backers in 1979, whose reverberations we are still living with.

In Guatemala in 1954, Wisner staged a coup to oust another elected official who was too progressive for Washington’s taste, President Jacobo Árbenz. The excuse was that his land and tax reforms showed him to be communist. If Árbenz “is not a communist,” Wisner’s man in Guatemala cynically cabled him, “he will certainly do until one comes along.” The coup triggered a brutal, decades-long civil war between rebels and a string of US-backed military dictators that left more than 200,000 Guatemalans dead and provoked still more to emigrate to safety abroad, mostly in the United States.

Wisner also arranged to parachute or infiltrate hundreds of operatives into Soviet-dominated Eastern Europe as well as overseeing the MK-Ultra program, which experimented with giving mind-altering drugs to unwitting subjects. He had a major hand in secretly subsidizing, on a huge scale, dozens of supposedly private independent groups like the US National Student Association, the Free Trade Union Committee, the American Society of African Culture, the International Commission of Jurists, and the Congress for Cultural Freedom. When investigative journalists at Ramparts magazine and elsewhere revealed all this in the late 1960s, it was a major boon for Soviet propaganda, tarnished the various groups involved, and, among their employees and grantees, shattered hundreds of relationships between those in the know and those who had now discovered that a key secret had been kept from them.

Douglas Waller’s new biography, The Determined Spy, is not the first study of Wisner—he is one of the central figures, for instance, in Scott Anderson’s trenchant The Quiet Americans: Four CIA Spies at the Dawn of the Cold War—but it is certainly the most thorough. And through Wisner, Waller offers us a picture of a postwar America that felt it had the power, and the right, to craft the rest of the world to its liking. That power also included the ability to influence what people in the United States knew about the rest of the world. More on that in a moment.

From an early age, Frank Wisner fit the mold of many of the CIA’s top officials: He came from a wealthy family; he was a member of the elite Council on Foreign Relations; he spent a few years at a Wall Street law firm and, during World War II, in the cloak-and-dagger Office of Strategic Services run by “Wild Bill” Donovan. (Donovan’s peacetime law firm was even in the same building as Wisner’s.) The intense, high-living Wisner took happily to wartime spy work, enjoying an extramarital affair with a young Romanian princess while managing various OSS operations from a luxurious mansion in Bucharest. As the war ended, Wisner managed to arrive in a newly conquered Berlin soon enough to grab some medals and a sketchbook as souvenirs from Hitler’s bunker.

The Allied victory in World War II gave OSS veterans like Wisner a boundless confidence that they could accomplish almost anything. This arrogance lasted for some two decades. The hard-driving Wisner was the principal drafter of a 1951 document known as the Magnitude Paper. It proposed to greatly increase the CIA’s budget in order to roll back communist advances in Eastern Europe—and China. Wisner predicted a Soviet invasion of Western Europe; the agency’s operations, he contended, must expand exponentially to meet the threat.

That invasion, of course, never came, and the hundreds of agents the CIA slipped into the Soviet satellite states were almost all killed, captured, or took the money and ran. Even when opposition to the USSR emerged, it rarely came from them. The Soviets were convinced that the CIA had instigated the 1956 Hungarian revolt against their rule, but ironically that uprising took Wisner and his colleagues totally by surprise.

Wisner’s comrades may have been full of bravado and ineffectual scheming where Europe was concerned, but it proved easier for them to influence events in the Global South. There, in the eyes of Eisenhower-era Washington, any country that claimed to be neutral in the Cold War was an enemy—as was any that might threaten Western economic interests. Hence the CIA’s interventions in Iran (protecting a huge British oil company) and Guatemala (protecting United Fruit—a client of CIA chief Allen Dulles’s former law firm).

The CIA’s next major operation of that kind was the sordid 1960–61 ousting and assassination of Congo Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba, who was seen as a threat to Belgian and American investments. This was one of the rare bits of the era’s skulduggery in which Wisner was not involved. The reason is that his behavior had begun to worry those around him. He screamed at his subordinates and tried to micromanage them; he went on manic shopping sprees. Shortly after the Soviets suppressed the Hungarian uprising, at a restaurant in a Vienna suburb, Waller writes, “Wisner stood up and announced in a loud voice to the other diners that Russian tanks had assembled at the border and would storm into Austria at any time.” It was an eerie echo of Forrestal’s paranoia.

Some months later, Wisner spent nearly half a year receiving psychotherapy and electroshock treatments in a private mental institution in Maryland, the Sheppard Pratt Hospital. It was a remarkably luxurious place with a greenhouse, a large library, a swimming pool, tennis courts, and a small golf course. After this, Wisner returned to duty. He was no longer masterminding coups but was appointed as the CIA’s station chief in London.

Two years later, however, the paranoia and mania returned. Wisner underwent more electroshock treatments in London, then was recalled and given a make-work job in Washington. After being awarded the CIA’s Distinguished Intelligence Medal and a consulting contract, he finally resigned in 1962, at the age of 53. As the Vietnam War heated up, he became a virulent hawk and developed a number of obsessions, including the belief that Hitler’s deputy Martin Bormann was hiding in South America. Old friends cut him off. Another round of shock treatments did not help. In 1965, Wisner put a shotgun to his head and pulled the trigger.

Any of us can fall prey to mental illness, and there were certainly fewer effective treatments and drugs for it 65 years ago than today. Luckily, Wisner’s family and colleagues got him into the sanitarium before he could act on his belief that Soviet tanks were about to pour across the Austrian border. But his life raises a larger question: When it comes to the belligerence of the United States during the Cold War, where do we draw the line between sanity and madness? Is it more irrational to imagine those invading tanks than to believe that you can replace the democratically elected government of Iran with an absolute monarch and not suffer consequences for decades to come? Or to believe that you can covertly fund scores of supposedly independent private organizations for years without undermining the faith in everything they stood for once that secret leaks out?

We can ask the same question about the man who now ultimately controls the CIA and so much else. Which is the more demented—to suggest injecting disinfectant as a cure for Covid or to claim that we can pour unlimited amounts of carbon into the atmosphere without catastrophically overheating the earth? That is a belief worthy of Caligula or George III.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Finally, Waller’s biography makes one other haunting aspect of Wisner’s life visible: An astonishing number of people in his immediate circle were journalists. Eric Sevareid of CBS was a bird-hunting comrade. The columnists Stewart and Joseph Alsop were constant companions, and Wisner persuaded the latter several times to produce columns backing the CIA’s preferred autocrats in Southeast Asia. “By the mid-1950s,” Waller writes, “Joe Alsop considered Wisner his closest friend in Washington.” Wisner and his wife, Polly, were also extremely close to Philip Graham, publisher of The Washington Post, and his wife, Katharine. They attended each other’s parties, and Polly and Katharine had a daily morning phone call to keep each other apprised of Washington gossip.

In the case of the Iran coup, Waller says, “the Alsop brothers and a handful of other reporters in Washington had known about the CIA plot ahead of time but printed nothing on it.” This raises the question: How many other coups or supposedly independent front organizations that Wisner was managing did journalists in the know keep silent about? Even the pathbreaking Church Committee probe of the CIA in 1975–76 was largely stonewalled from investigating how the agency used a compliant press.

There was certainly much to uncover. When a CIA U-2 reconnaissance plane was shot down over the Soviet Union in 1960, the reporter Erwin Knoll told Carol Felsenthal, the author of Power, Privilege and the Post, that he’d once found himself in an elevator with a Post editor who told him, “We’ve known about those flights for several years, but we were asked not to say anything.” Key people at The New York Times also knew and kept quiet, David P. Hadley reported in The Rising Clamor: The American Press, the Central Intelligence Agency, and the Cold War.

Carl Bernstein revealed in Rolling Stone that Katharine Graham, who had succeeded her late husband as the Post’s publisher, once asked CIA chief William Colby if anyone on her staff was working for him. “Colby assured her that no staff members were employed by the Agency but refused to discuss the question of stringers,” Bernstein writes, adding that “more than 400 American journalists…have secretly carried out assignments” for the CIA.

We will never know how many of those assignments were hatched in the corners of the lavish parties at the Wisners’ Georgetown home. Waller does not speculate about this, but he does mention that Wisner kept a wire-service teletype next to his office so he could monitor the news all day. If it was not to his liking, he acted. When British correspondents wrote critically of what the United States was doing in Guatemala, he had the State Department put pressure on Winston Churchill. When the Times reporter Sidney Gruson did the same, Wisner had the CIA gather information on him, and Allen Dulles got the Times to remove Gruson from the Guatemala beat.

The CIA’s hostility to all-too-rare critical journalism continued after Wisner’s departure from the agency. I worked at Ramparts at the time the magazine started to unravel the CIA’s widespread secret funding of private organizations. When, years later, I received my heavily redacted copies of CIA files under the Freedom of Information Act, there were dozens of pages on me, even though I was an extremely junior and unimportant staff member. The agency had a “Ramparts Task Force” of 12 agents that, among other work, prepared a briefing on the magazine for the director. They were watching us so closely that they did something that even we never had the time to do: compile an index, by subject and author, of the articles we’d published.

Journalism like this was rare; the Alsops were more typical. I doubt if it was the author’s main intention in writing The Determined Spy, but the book is a reminder of how easily the American media can be cajoled into serving as another branch of government. On that score, the next four years will be a severe test.

More from The Nation

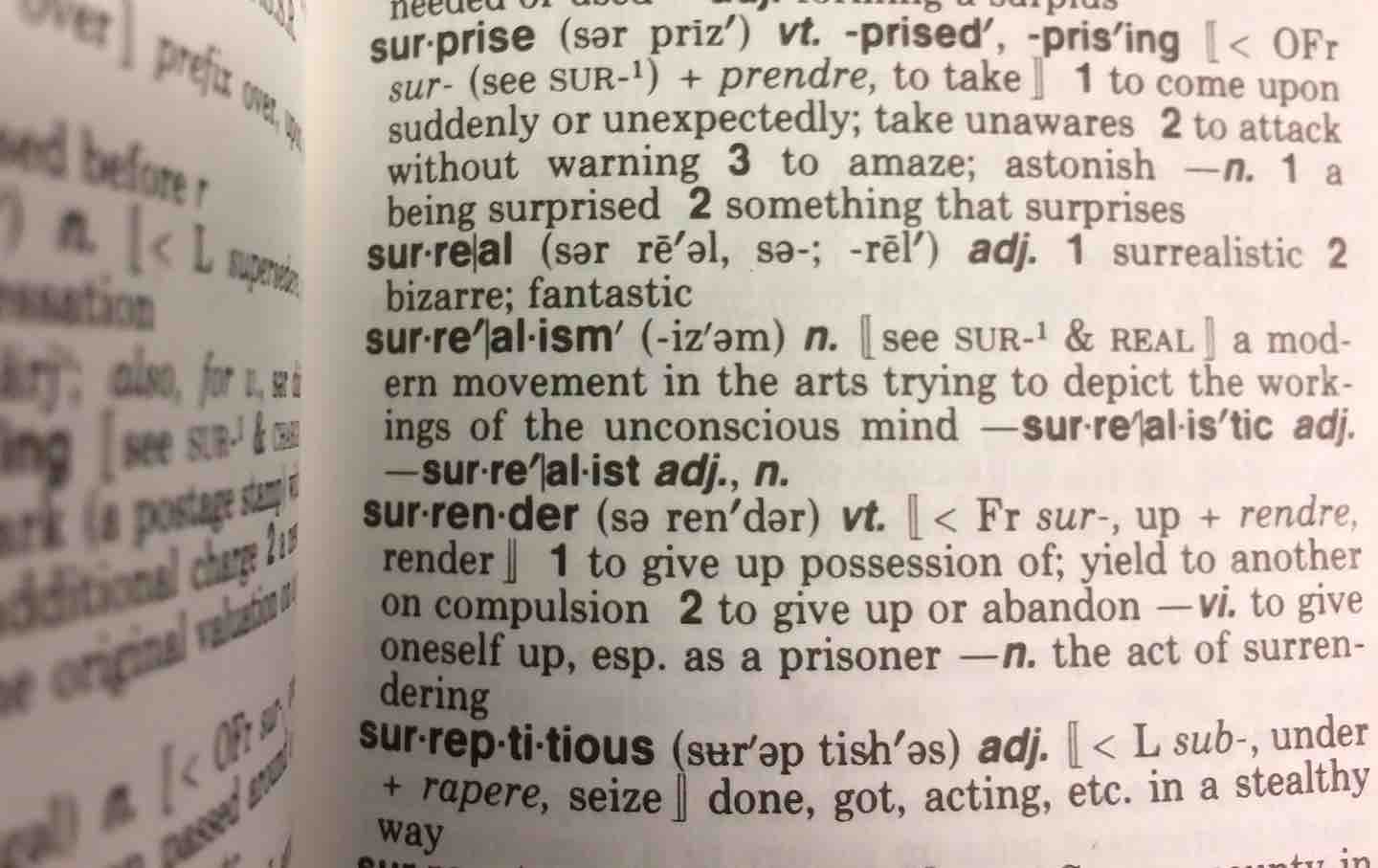

Can the Dictionary Keep Up? Can the Dictionary Keep Up?

In Stefan Fatsis’s capacious, and at times score-settling, personal history of the reference book, he reveals what the dictionary can still tell us about language in modern life

Why We Misunderstand the Chinese Internet Why We Misunderstand the Chinese Internet

Journalist Yi-Ling Liu’s The Wall Dancers traces how the Internet affected daily life in China, showing how similar this corner of the Web is to the one experienced in the West.

The Bad Vibes of “Wuthering Heights” The Bad Vibes of “Wuthering Heights”

Keeping its distance from the novel, Emerald Fennell’s film ends up offering us a mirror of our own times.

Has Contemporary Fiction Ignored the Working Class? Has Contemporary Fiction Ignored the Working Class?

Claire Baglin’s bracing On the Clock gives its readers a close look at work behind the fry station, and in the process asks what experiences are missing from mainstream letters.

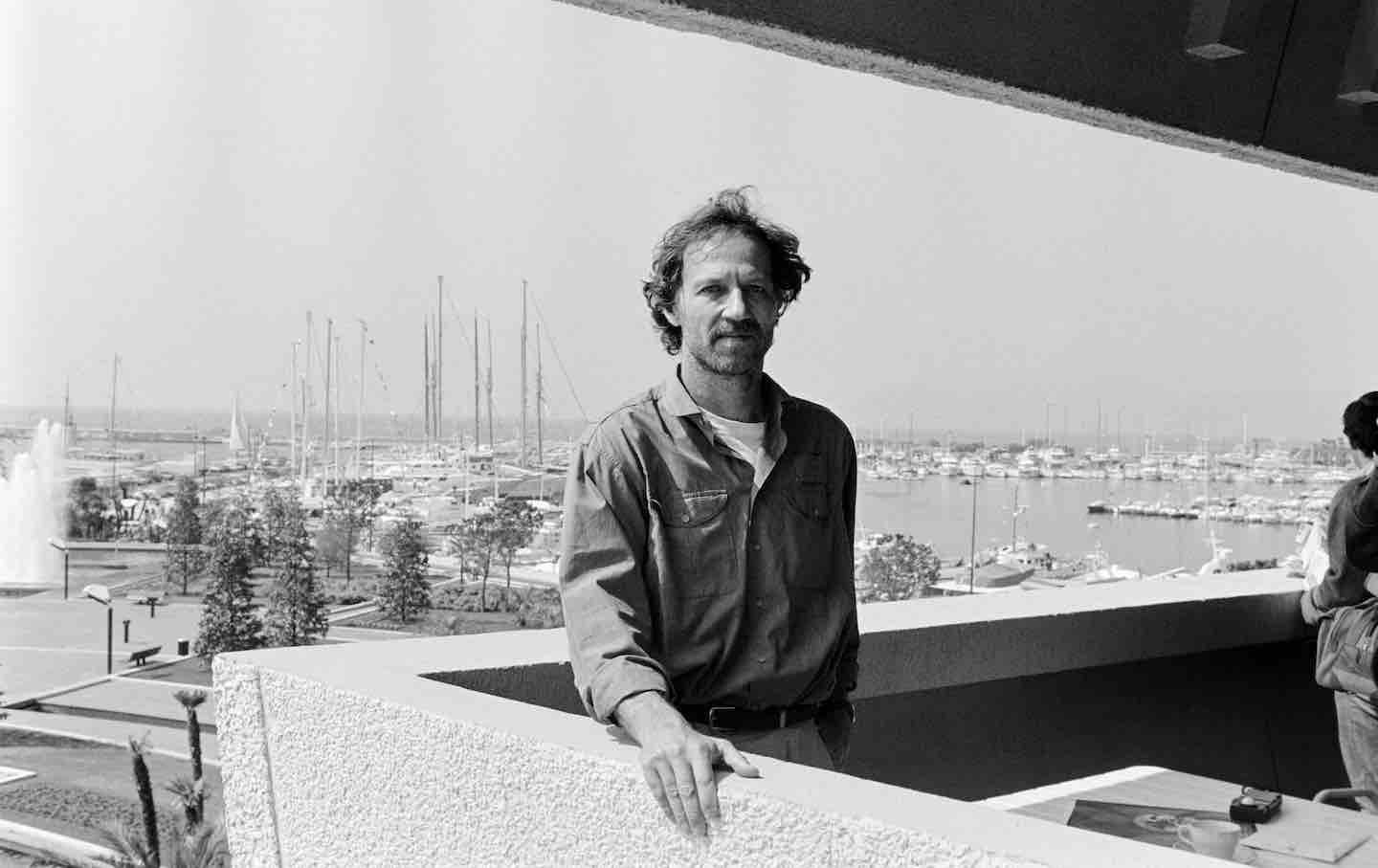

Werner Herzog Between Fact and Fiction Werner Herzog Between Fact and Fiction

The German auteur’s recent book presents a strange, idiosyncratic vision of the concept of “truth,” one that defines how he sees the world and his art.

Do Humans Really Understand the World’s Disorderly Rivers? Do Humans Really Understand the World’s Disorderly Rivers?

In James C. Scott’s last book, In Praise of Floods, he questions the limits of human hegemony and our misplaced sense that we have any control over the Earth’s depleted watershed....