A few weeks ago I spoke to a class of 12th-graders in a Brooklyn public school about what it’s like to be a journalist. The students were curious about whether my life had ever been endangered while reporting a story (no), whether anyone had ever gotten angry with me for asking unwelcome questions (yes), and whether any journalists have become rich and famous (yes, but not often those who ask unwelcome questions). They were especially interested in the idea of telling stories with images, not words. One, an adept at Instagram, had never heard of photojournalism, and was intrigued. Two other students said they were into painting and drawing, but I somehow didn’t think to tell them that some of the most exciting and subversive American journalism has taken the form of illustration. Had I visited the Queens Museum’s current exhibit of drawings by William Gropper before my classroom talk, I wouldn’t have made that mistake.

Once renowned and now largely forgotten, Gropper’s work offers a lasting lesson in how useful pencils and paintbrushes can be in the fight against the exploitation of the many for the profit and amusement of the few. The first career-spanning exhibit on Gropper since the early 1980s, “Bearing Witness: Drawings of William Gropper” (through July 31) presents 70 drawings and two paintings from a private collection, together comprising a considerable, if by no means exhaustive, survey of his half-century-long career. Staking a claim to contemporary relevance, an introductory panel promises visitors that Gropper’s work “addresses issues of political hypocrisy, surveillance and censorship, genocide and immigration that resonate with the current sociopolitical climate.”

And it does. But the presentation of that work is not as useful as it might have been. The exhibit would not be possible, the introductory panel says, without “the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature.” That serves, in effect, as a trigger warning: The reputation of a radical and prophetic artist, once hounded out of work by the forces of reaction, is being restored at just the moment when the political faith he subscribed to has come back into vogue. Here, and not only here, it is watered down in the process. “Human rights” appears several times, while “socialism,” a word and philosophy that Gropper was proud of, is nowhere to be found. One panel refers without elaboration to his “lifelong interest in the failure of democracy.” Asked how she went about presenting Gropper’s radical politics in a way that would be accessible for a general audience, the exhibit’s curator told me it required “walking a fine line in terms of celebrating somebody who did cross all of the lines.”

* * *

Gropper was born to a pair of immigrant Jews on the Lower East Side in 1897. His father, Harry, had studied in several European universities and learned eight languages before immigrating to New York and finding little to do with his learning. He finally got work in a garment factory, where he met Jenny Nidel, also a new arrival. “The sweatshop gave us our livelihood but robbed us of our mother,” Gropper later recalled. (He once said that unlike Whistler, who famously depicted his mother as a solemn and dignified stoic, he would have painted his own as bending over a bathtub or a sewing machine.) Gropper spent his childhood getting pummeled by various gangs and drawing sidewalk pictures of cowboys and Indians that wrapped around the block. In 1911, a favorite aunt perished along with 145 other workers, most of them young Jewish women, in the devastating fire at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in Greenwich Village. To say, as the museum does, that Gropper “was exposed to the rigors of the working class at a young age,” severely understates the point.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

In 1915, Gropper was offered a scholarship to the New York School of Fine and Applied Arts by its founder (and now namesake), Frank Parsons. He began winning prizes for his work, including one for his cartoons, leading to his hiring by the New York Tribune as a sketch artist for feature stories. For the next several decades—in, as the museum tells us, “mainstream periodicals as well as more marginal publications,” including this one—Gropper “left a record of graphic comment on the twentieth century unique for its forceful presentation of ideas and lampooning of society’s ills,” as the late Joseph Anthony Gahn wrote in his 1966 dissertation, “The America of William Gropper, Radical Cartoonist.” (Shamefully, Gahn’s work is the closest thing we have to a proper telling of Gropper’s life.)

One Depression-era poster by Gropper declares: against capitalist terror: against all forms of suppression of the political rights of workers. That now-neglected word, “suppression,” often appears in Gropper’s work, and as far as words go, it is, as the current leader of the Republican Party might say, one of the best. It appears again in a late 1930s drawing that, to my mind, offers a far more compelling visual metaphor for entwined grievances and social causes than the currently fashionable idea of “intersectionality.” Gropper’s drawing has a single tree with several of what the accompanying panel calls “negative influences” branching out from it: “war profits,” “race hatred,” intolerance, Charles Coughlin, “anti-labor propaganda,” the collusion of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and FBI director J. Edgar Hoover. Gropper called the drawing suppression. In his mind all of those scourges are connected at the roots. By contrast, intersectionality asks us to think of lines that meet only for a moment, before again going their separate ways.

The truly subversive idea—quite incompatible with Governor Cuomo’s thinking, as I understand it—that “race hatred” and “war profits” branch from the same rotten tree is not explored by the exhibit, which prefers to describe Gropper’s politics in terms more appropriate to today’s identity-based progressivism than to the socialism of the 1930s, when it would have been thought pathetically defensive to add the redundant modifier “democratic.” On this strained reading, Gropper was a proto-multiculturalist who “made great efforts to counter a general and widespread fear of anyone who was ‘different.’” He should interest us today not for his insistence on the kinship between capitalism and terror, but because he “focus[ed] on the diversity and strength of an American workforce that was coming together to create collective change.”

* * *

Yet the obvious implication that Gropper so easily sympathized with those who were “different” because he was, too, doesn’t quite hold up. Gropper’s relationship to Jews and Jewishness was fraught. According to Gahn, Gropper was turned off by organized religion while studying Torah in a “damp cellar below a synagogue on East Broadway” with a rabbi who, to punish the boy’s wrong answers, “pinched him all over his body.” He also had quibbles with the doctrine: The story of Adam and Eve, who had to wear fig leaves after becoming conscious of their nakedness, reminded Gropper of his parents slaving away in the garment factory. His early work occasionally bordered on the egregious, as in a 1925 cartoon he published in New Masses that showed three businessmen wearing yarmulkes. “God forgive us for oppressing the people so much,” one says, “because we do not know how to do anything else.”

After the rise of Hitler, Gropper took a different tack. “Gone were the former diatribes against kosher businessmen, imperialistic Zionists, and rabbinical fakers,” Gahn wrote. “Gropper’s childhood sufferings shared with thousands of other Jews on the East Side seemed at last to have emerged as a strong feeling of brotherhood in the face of Hitler’s horrible persecutions.” In “Warsaw Ghetto,” published in a Jewish monthly called New Currents in 1943, Nazi toughs hassle women and children forced to march along in a line; in another picture, the same three goons haul off a looted Torah and menorah from a pile of burning bodies. The current exhibit includes a Yiddish book with the artist’s name on the cover, spelled out in Hebrew letters, right to left. Explaining his postwar works showing rabbis’ hands plaintively reaching up to the sky, Gropper described himself as “not Jewish in a professional sense but in a human sense”—yet another salient distinction we appear to have all but lost.

* * *

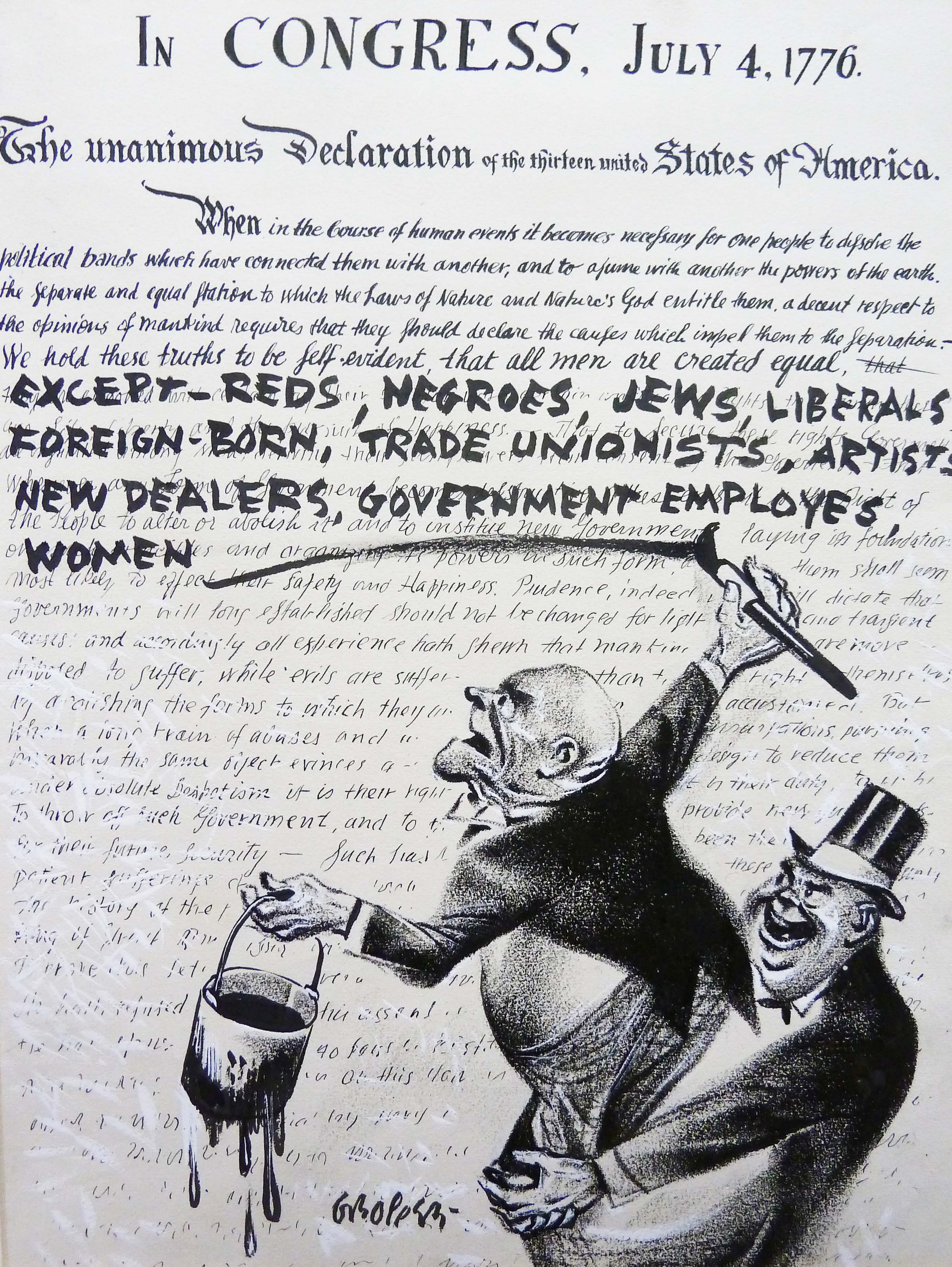

It occasionally happens to me at art museums, if I’m in a certain mood, that I get so lost in a picture I need to be coughed away by another visitor wanting to have a look or warned to back up a few inches by an irritated guard. This mood came over me while looking at Gropper’s drawing of a banker hoisting up a painter to add the words, except reds, negroes, jews, liberals, foreign-born, trade unionists, artists, new dealers, government employees, women to the Declaration of Independence, underneath “all men are created equal.” I was only roused from the spell by an employee of the museum explaining her appreciation of the image to a smartly suited man. “You could just change Jews to Syrians,” she said, “and it would be the same thing as today.”

In our eagerness to draw parallels between the present and the past, we often avoid discussing the actual similarities and differences between another time and our own. There is a tendency to do this on the left nowadays that is directly related to—indeed, probably proportional to—the active suppression of dissidence in the United States for the last 75 years. The results are both gestural politics and unsatisfying art: revolution as a marketing campaign and presidential campaigns that call themselves revolutions.

In his classic 1961 study Writers on the Left: Episodes in American Literary Communism, the scholar Daniel Aaron, who died on April 30 at the age of 103, quoted Gropper, writing in New Masses, about the vigil he kept with Edna St. Vincent Millay, John Dos Passos, Dorothy Parker and others on the night that the Italian anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti were executed by the state of Massachusetts. Together, they watched as the “two black hands of the death clock” approached midnight. “Soon on a board near us appeared the words, Sacco, Vanzetti Dead,” Gropper wrote. “Then nothing mattered, nothing except the morrow…for I knew the workers would remember.” As it turns out, they could use some help.