Ruthelle Frank, an 87-year-old resident of Brokaw, Wisconsin, has voted in every presidential election since 1948. But after the passage of Wisconsin’s voter-ID law in 2011, she became one of 300,000 registered voters in the state without the required ID. Frank was paralyzed on the left side of her body at birth and doesn’t have a driver’s license or birth certificate. Her name is misspelled in Wisconsin’s Register of Deeds, an error that would cost hundreds of dollars to correct.

These circumstances led Frank to become the lead plaintiff in a challenge to Wisconsin’s voter-ID law. That law was blocked in state and federal court for the 2012 election and struck down in May 2014 following a full trial, only to be reinstated by a panel of Republican judges on the US Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit less than two months before the 2014 election. The Supreme Court prevented the law from taking effect for the 2014 election, but only on a temporary basis. After the election, voting rights advocates asked the high court to consider the full merits of the case. Today, the Supreme Court declined to hear the appeal. As a result, Wisconsin’s voter-ID law—among the most restrictive in the country—will be allowed to go into effect.

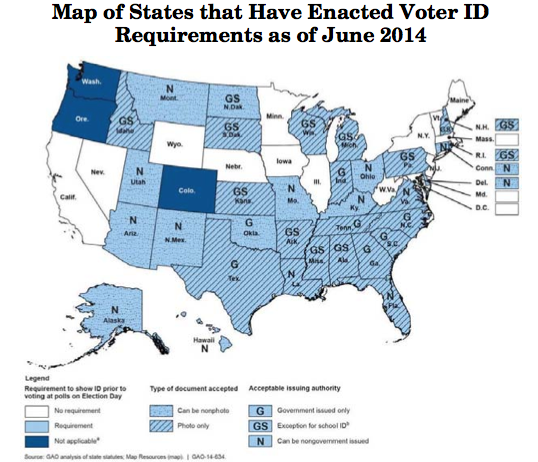

In 2008, the Supreme Court upheld Indiana’s voter-ID law in Crawford v. Marion County. The Wisconsin case presented an opportunity for the Court to reconsider the issue. At the time of the Crawford decision, only two states—Indiana and Georgia—had passed voter ID laws and little was known about their impact. Since Crawford, seventeen states have passed voter ID laws—nine of them requiring strict forms of government-issued ID, like in Wisconsin—and much more is known about the burdens of such laws.

[Source: Government Accountability Office]

There is compelling evidence that the Wisconsin law is significantly more burdensome than the voter ID law approved in Indiana.

1. Wisconsin’s law is more notably restrictive than Indiana’s.

According to Judge Richard Posner of the Seventh Circuit:

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

The Indiana statute challenged in Crawford was less restrictive than the Wisconsin statute challenged in this case. Indiana accepts any Indiana or U.S. government-issued ID that includes name, photo, and expiration date. Wisconsin’s statute permits voters to use only a Wisconsin drivers’ license or Wisconsin state card, a military or tribal ID card, a passport, a naturalization certificate if issued within two years, a student ID (so long as it contains the student’s signature, the card’s expiration date, and proof that the student really is enrolled in a school), or an unexpired receipt from a drivers’ license/ID application. Wisconsin does not recognize military veterans IDs, student ID cards without a signature, and other government-issued IDs that satisfy Indiana’s criteria.

Voters 65 and over can vote absentee in Indiana without showing a government-issued ID and can use their Medicare, Medicaid or Social Security cards to obtain a driver’s license instead of a birth certificate—neither of which is true in Wisconsin.

Three hundred thousand registered voters in Wisconsin, nearly 10 percent of the electorate, lack a valid voter ID, compared to only 43,000 in Indiana, less than 1 percent of the electorate.

This matters a lot, since new states passing voter-ID laws, like Texas and North Carolina, claim they are following the Indiana template upheld by the Supreme Court, when in reality they are adopting laws that are far more restrictive.

2. Voter ID is much more difficult to obtain in Wisconsin than Indiana.

From an amicus brief filed by the One Wisconsin Institute:

Although Wisconsin has 50 percent more square mileage than Indiana, Indiana has 140 BMV [Bureau of Motor Vehicle] service centers, compared to Wisconsin’s 92. In addition, whereas Wisconsin has only 33 full-time locations, nearly all of Indiana’s 140 BMVs are open five days a week. Indiana also has 124 BMVs open on the weekends. Wisconsin has three.

The state is not exactly making it easy for voters to comply with the new law.

3. The debate over voter ID laws has shifted significantly since the Crawford decision.

In Crawford, the Supreme Court said that Indiana had a compelling interest in preventing voter fraud, even though the state presented no evidence of voter impersonation to justify the law. Seven years later, however, it’s clear there’s no practically no evidence of voter impersonation in America, whereas the burdens of voter ID laws are much better understood.

Justice John Paul Stevens, who wrote the Crawford decision, is now a critic of voter ID laws. “My opinion should not be taken as authority that voter-ID laws are always OK,” he told The Wall Street Journal in 2013. “The decision in the case is state-specific and record-specific.”

Stevens now says he agrees with Judge Souter’s dissent in the case. “As a matter of actual history, he’s dead right. The impact of the statute is much more serious” on poor, minority, disabled and elderly voters than the evidence in the 2008 case indicated, Stevens said.

The same is true for Judge Posner, who wrote the opinion upholding Indiana’s voter ID law in the Seventh Circuit but published a scathing critique of Wisconsin’s voter ID law last year. “There is evidence both that voter impersonation fraud is extremely rare and that photo ID requirements for voting, especially of the strict variety found in Wisconsin, are likely to discourage voting,” Posner wrote. “This implies that the net effect of such requirements is to impede voting by people easily discouraged from voting, most of whom probably lean Democratic.”

Posner concluded that claims of voter impersonation fraud were “a mere fig leaf for efforts to disenfranchise voters likely to vote for the political party that does not control the state government.”

Judge Lynn Adelman of the US district court in Wisconsin reached the same conclusion. “The evidence at trial established that virtually no voter impersonation occurs in Wisconsin,” Adelman wrote. “The defendants could not point to a single instance of known voter impersonation occurring in Wisconsin at any time in the recent past…. It is absolutely clear that Act 23 will prevent more legitimate votes from being cast than fraudulent votes.”

4. Wisconsin’s law violates the Voting Rights Act.

Indiana’s law was not a case about voting discrimination. But in Wisconsin, Adelman found that “the evidence adduced at trial demonstrates that this unique burden disproportionately impacts Black and Latino voters,” he wrote. Data from the 2012 election “showed that African American voters in Wisconsin were 1.7 times as likely as white voters to lack a matching driver’s license or state ID and that Latino voters in Wisconsin were 2.6 times as likely as white voters to lack these forms of identification.”

Would these facts have convinced the Roberts Court to strike down Wisconsin’s voter ID law? Maybe. Or maybe not. This is the same Court that gutted the Voting Rights Act two years ago, despite widespread evidence of contemporary voting discrimination. Chief Justice John Roberts and his conservative colleagues could have used the Wisconsin case as an opportunity to offer a blanket endorsement for all voter ID laws, something that Stevens did not do in Crawford, setting a chilling precedent for voting rights for decades.

That’s why many voting rights advocates were agnostic about this case and felt more comfortable with the Court’s eventually hearing a challenge to voter-ID laws from a state like Texas, where a trial court found the law was enacted with intentional discrimination. It may also explain why the liberal justices on the Court did not vote as a bloc for the Wisconsin case to be heard.

At the same time, the Court’s decision not to hear the case means that one of the most restrictive laws in the country, in a crucial swing state, will now stand, and the broader constitutionality of voter ID laws will not be resolved before the 2016 election.

When it comes to the current Supreme Court and voting rights, the options range from bad to worse.