Uncles don’t fare terribly well in history or literature. From Creon to Claudius, Uncle Sam to Uncle Scar, the role of Father’s younger or Mother’s older brother tends to be a dubious one, shaded by jealousy, vengefulness, and a penchant for fratricide. There are exceptions, to be sure: Pip’s sweet but simple uncle, Joe Gargery. Peter Parker’s ill-fated Uncle Ben. But even at their best, they rarely take the shape of crusading activists against US imperialism. Or legal warriors against war criminals. Or the implacable scourges of torturers. They do not, as a rule, serve legal papers to blood-stained generals at their Harvard graduations. But my Uncle Michael did. And in this way, as in so many others, he defied imagination—and redefined reality.

Last week, on Wednesday, I lost this beloved uncle of mine. He slipped away after a brief but torrential illness, a vigorous 72-year-old with years of fight—and decades of outrage—still inside him. In the days before his death, close friends and family streamed into his hospital room, one last love-in. Michael’s son brought a banjo, his friend a guitar. We sang songs, watched old videos, rehashed favorite memories, and cried a lot. All of us. Dear cousins who’d grown up with Michael in Cleveland. Dear friends who’d gotten beaten up with him at Columbia. Friends from the legal trenches, friends from struggles that spanned the globe. Even nurses and doctors who had grown attached to him in their too-short time together. “I know this is unprofessional,” one broken-up physical therapist confessed as she rushed into his hospital room, “but I had to come by when I heard.”

In the days since Michael’s death, the outpouring of love and grief across the continents, from friends, acquaintances, and complete strangers, has comforted and stunned us. The pain—and beauty—of the moment is that it would have stunned Michael, too. For all the people he touched and inspired, for all the audacity of his political work, I believe he had no idea of his far-reaching influence. As each new tribute rolls in, I imagine him clapping his right hand over his mouth—a favorite gesture when he was shocked or moved—and shaking his head back and forth while letting out an emphatic “Whoaaaaaa!”

In some ways, I understand this. We in his family always knew that Michael was extraordinary, brilliant, and passionate—the best and boldest there was. But I don’t think we fully realized how extraordinary he was to so many other people. This was in part, I suspect, because Michael didn’t talk all that much about his work—which is to say, his particular role in any of the many struggles he had dedicated himself to. He would talk about the struggles themselves—about the abuses that moved him to action—but, as his wise friend Rashid Khalidi observed, Michael was always far more interested in finding out about other people than in talking about himself. He had an amazing enthusiasm for people, and when he was with you, he wanted to hear about your work, your children, your parents, your fears, your hopes and accomplishments.

But for me, at least, I think there’s another reason for the surprise: My relationship with Michael was so deeply personal, so entwined not only with the big questions of war, peace, justice, and injustice, but also with the more intimate questions of family, parenting, birth, death, holidays, vacations, aspirations, disappointments, anxiety, depression, and joy—all the strands that weave together to form the fabric of our daily lives. Michael was, quite simply, a defining force for me. He was my mentor and guardian, my jester and wise counsel, and so much of what I have done, small and fragmentary as it is, is because of him. I guess I couldn’t imagine that he could mean so much to so many others, too.

This connection to Michael—powerful and encompassing—goes all the way back to my beginning. I had no consciousness in my earliest days of the work that sent him careening through Central America—Nicaragua, Guatemala, El Salvador—but I knew I adored him. Back then, Michael wore a full black beard, part Che Guevara, part Vilna Gaon, and whenever that beard came around, I knew the fun would begin. He would throw my sister and me over his shoulders like sacks of potatoes, hurl us squealing into the air, shake our hands until they almost dropped off.

Michael loved kids. He had a fantastically goofy side, and he could keep us entertained for hours. But I also think that he connected so well with us, and with the scads of kids who followed—his own children above all, but also his friends’ children—because, for all his jokes and silliness, he took young people seriously, respected their still-forming minds. Plus, kids were some of the only people who could go toe-to-toe with him in curiosity and enthusiasm. In the brutal days before his death, just before he went into the hospital for the last time, Michael’s daughter discovered that he’d been searching for videos of how to draw cardinals. He had wanted to send them to my son.

In my own life, Michael’s respect for the minds of the under-10 set meant that he never talked down to me, always assumed that I could and should understand. He spoke of the world as it was, and as I got older, that meant he became not only fun but interesting. It was the early 1980s, a moment of revolution in Latin America and Reagan’s counterrevolution at home, and when Michael was around, conversation inevitably turned to issues both mysterious and grown-up. He used words like “Managua” and “Nicaragua,” “Sandinista” and “contra,” and in 1982, he took my whole family to Cuba, not long before he and the Center for Constitutional Rights sued the Reagan administration over its draconian restrictions on Cuban travel. I’m ashamed to admit that I was more interested in guzzling as much Tropi-Cola as I could than in absorbing the lessons of the Cuban Revolution. Nonetheless, a halo of nascent comprehension was beginning to form at the fringes of my consciousness. Though I didn’t realize it then, Michael was laying stones in the forest for me to follow when the time came.

Michael kept laying these stones, bigger, more deliberate, as I got older—suggesting that I write about the bombing of Cambodia for a 10th-grade term paper, subscribing me to The Nation, giving me a copy of Living My Life, Emma Goldman’s autobiography. I’d like to think that Michael saw in me a receptive spirit, that he recognized the way the privilege of my childhood was raising more questions for me than I could answer on my own. But maybe he just realized that I was 16 and struggling with a splintering nuclear family, and he wanted to be present for me. He called to check in on me often. The phone would ring, and we would talk about whatever homework I was doing; his kids, who were just small, pixieish toddlers back then; and, eventually, the big case that had come to consume him—the illegal detention of HIV-positive Haitian refugees at the US Naval Base at Guantánamo Bay.

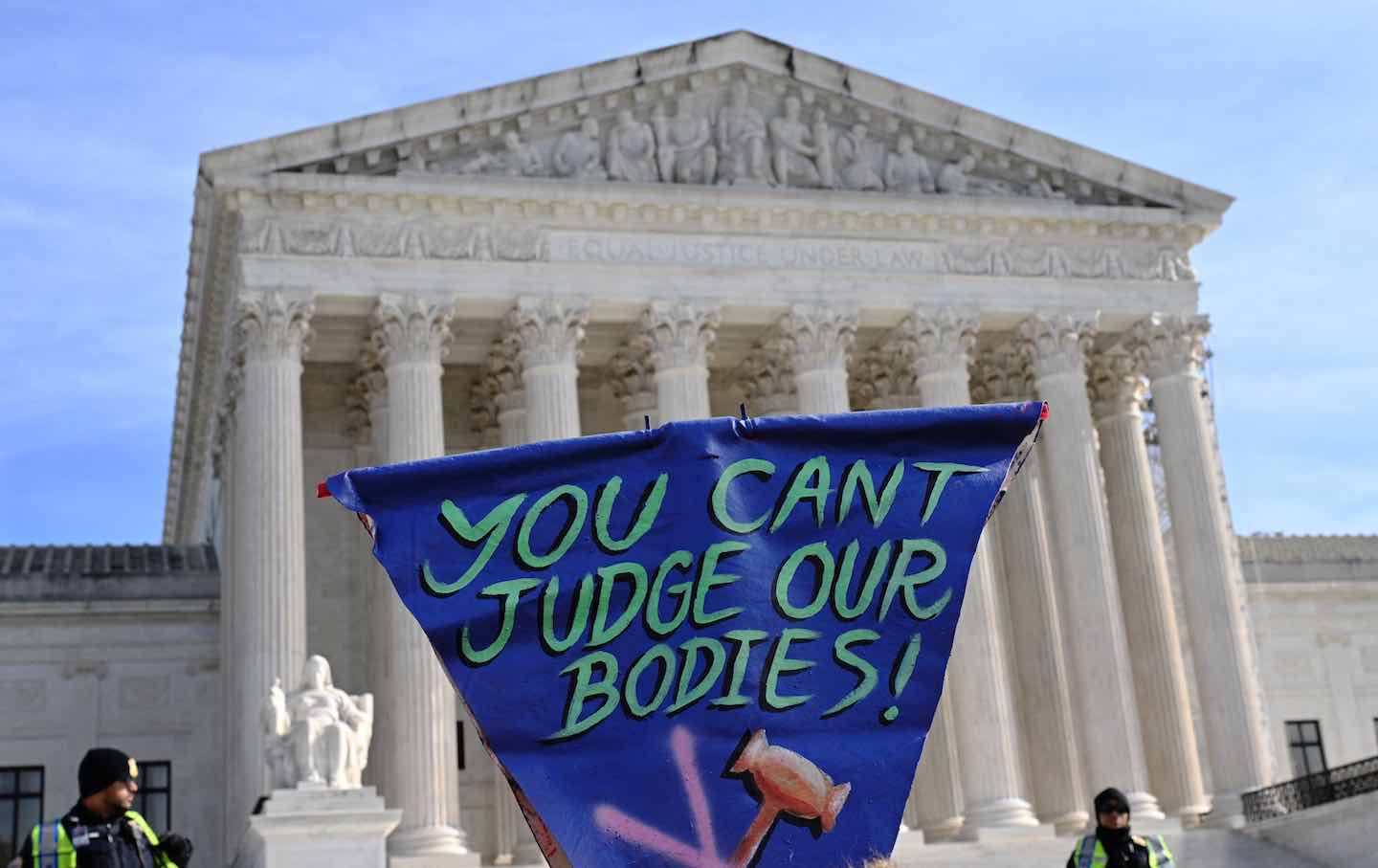

Guantánamo. For 14 years, it’s been synonymous with the barbarism and abuse of the “war on terror.” But before it became a modern-day penal colony, it was an open-air holding cell for more than 300 Haitian refugees: men, women, and children who had fled Haiti after the US-backed coup against Jean-Bertrand Aristide. For more than a year, Michael, along with Harold Koh and a group of Yale law students, worked every angle—legal, political, and grassroots—in a multi-pronged campaign to free the refugees. And, miraculously, they won.

It was a signal victory for Michael, a rare moment when the promise of legal rights trumped the power of government impunity, when organized compassion won out over naked cruelty. This cruelty, which Michael witnessed firsthand during visits to Guantánamo, shook him powerfully—so much so that, from the moment I read the news in January 2002 that the Bush administration planned to resurrect Gitmo for so-called enemy combatants, I knew that Michael would fight it. Damn the death threats, damn the opprobrium of the rah-rah jingoists and play-it-safe crowd.

Today, as I look back over the sweep of Michael’s life, his audacity stuns me. Back then and in the moment, however, it didn’t surprise me all that much. Like a kid who conjures magical powers for her parents, who is convinced they can take on dragons and vanquish bullies, I believed that Michael could fight and win the big, impossible battles that few others would: sue presidents, challenge dictators, pursue torturers. He made it seem so routine, almost easy, like just another day at the office.

Nor was it just the big battles that I relied on him to tackle. I also turned to him to work smaller, more personal miracles. When a woman I knew got slammed with serious health and legal troubles at the same time, I turned to Michael for legal guidance. When lawyer friends needed career advice, I sent them to him. And in my own life, I leaned on him constantly. I relied on him for political guidance, to give me the right read on an issue when I couldn’t parse it myself. I relied on him for professional counsel—to say nothing of internships and actual jobs—on the many occasions I was lost. I relied on him for lightning humor, brilliant ideas, off-kilter quirkiness, and reassurance. I relied on him—exactly 10 years ago this May—to perform my wedding.

And now? Now that Michael is no longer here, I feel bereft: hollowed out, diminished, and a little scared. I keep wondering who will nudge me to take the bolder path when the safer one seems so much easier; who will help me slice through ethical snarls when I can’t unravel them myself; and who will crack me up with a steady supply of bad Borsht Belt jokes and, just as often, whip-clever quips. On the day after Michael’s death, his son, Jake, wondered who will be our moral compass now that Michael can’t be. It’s a question I’ve been asking, too.

Michael, I suspect, would be somewhat mortified by all this gushing. He was too much of a rebel for pedestals, and he had little time for the Great Man theory of justice. He didn’t believe in men (or women), he advised me on a number of occasions; he believed in movements. In Black Lives Matter. Occupy Wall Street. The fight for Palestinian freedom. The struggle of the Sandinistas. The promise of South African trade unionists. The pursuit of Puerto Rican independence. And on and on.

“When change comes, it is unpredictable, but it does not happen by chance,” Michael told his close friend Anthony Arnove in an interview several years ago. “At some point,” he continued, “all of these small efforts coalesce, and we see the changes we want…. All of us need to light sparks all of the time, and then the time comes when justice is inevitable.”

Michael was right about the power of movements, about the quantum effect of lots and lots and lots of people working together. He wouldn’t have minded a few tears, but then he’d want us to get busy with the critical work of waging peace, forging racial justice, ending torture, stopping violence, and thwarting US imperialism. He’d want us to ignite change. But dear god, I will miss him as I stumble, arms outstretched toward the millions of tiny sparks, along the path he laid for me.