In our new political era of disinformation, climate-change denial, and ever-powerful industry lobbyists, unbiased science and research are under serious political attack. Underfunded agency pages have been wiped clean of environmental information, scientists have been barred from EPA chief advisory boards, and most recently, crucial public-health studies have been excluded from decision-making processes under the guise of “transparency.”

Meanwhile, a huge hole in federal accountability for our air, water, and land has left countless low-income communities with unsolved lead-contamination issues, stalled Superfund cleanups, coal ash polluting their waterways, and other foreseeable but heart-wrenching consequences of the federal regulatory rollback. With science policy and the data that fuel it under administrative attack, both the world of science at large and communities on the front lines of environmental catastrophes are losing what direct avenues they have left to hold the government responsible for a sustainable and safe future.

This is nothing new for grassroots groups, who have struggled for decades to get policy-makers to pay attention to local environmental-equity issues. But now, a growing movement of coders, activists, scientists, and organizers are radically breaking from the status quo by creating tools that put the ability to collect data and monitor environmental conditions in the hands of community members, ushering in a new front in the environmental resistance: community science.

“If we don’t have data coming from people who are supposedly enforcing and regulating for us—protecting our communities—then we need to figure out how we can take that accountability in our hands,” said Shannon Dosemagen, the executive director of Public Laboratory for Open Technology and Science, a community organization that aims to democratize science by addressing environmental issues from the ground up. And while the cutbacks on the federal and state level can’t be filled in by concerned volunteers, community science has many advantages over traditional, top-down scientific research.

Utilizing new technologies like cloud-based aerial mapping, DIY monitoring and engineering kits, and crowdsourcing software, Public Lab and groups like it are building inclusive and innovative new coalitions, prying the work of environmental monitoring research from the grips of politicized agencies and institutional experts and putting it into the hands of community members themselves. It’s a radical new way of doing science, and one uniquely suited to our era of rapid technological advancement and political impasse.

Dosemagen, a community organizer, Jeff Warren, a cartographer, and Liz Barry, now the group’s director of community development, and four other cofounders conceived of Public Lab after the 2010 Deepwater Horizon rig explosion spurred collective innovation out of tragic necessity. The largest marine oil spill in history and the catastrophic environmental disaster that ensued—wildlife covered in thick toxic sludge, glistening slicks leaking into vital fisheries and tributaries—came with an information blackout for residents along coastal Louisiana who weren’t getting clear answers about the extent of the damage in their backyards. In the community’s eyes, it seemed no one was accurately tracking what was happening on the ground.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

“We wanted to figure out ways that we could drive down the price point and make tools for monitoring really accessible, because back in 2010 we were mainly seeing tools that were being created for government, research institutions, or for corporations to do monitoring. It wasn’t at a price point that was acceptable to communities,” Dosemagen added.

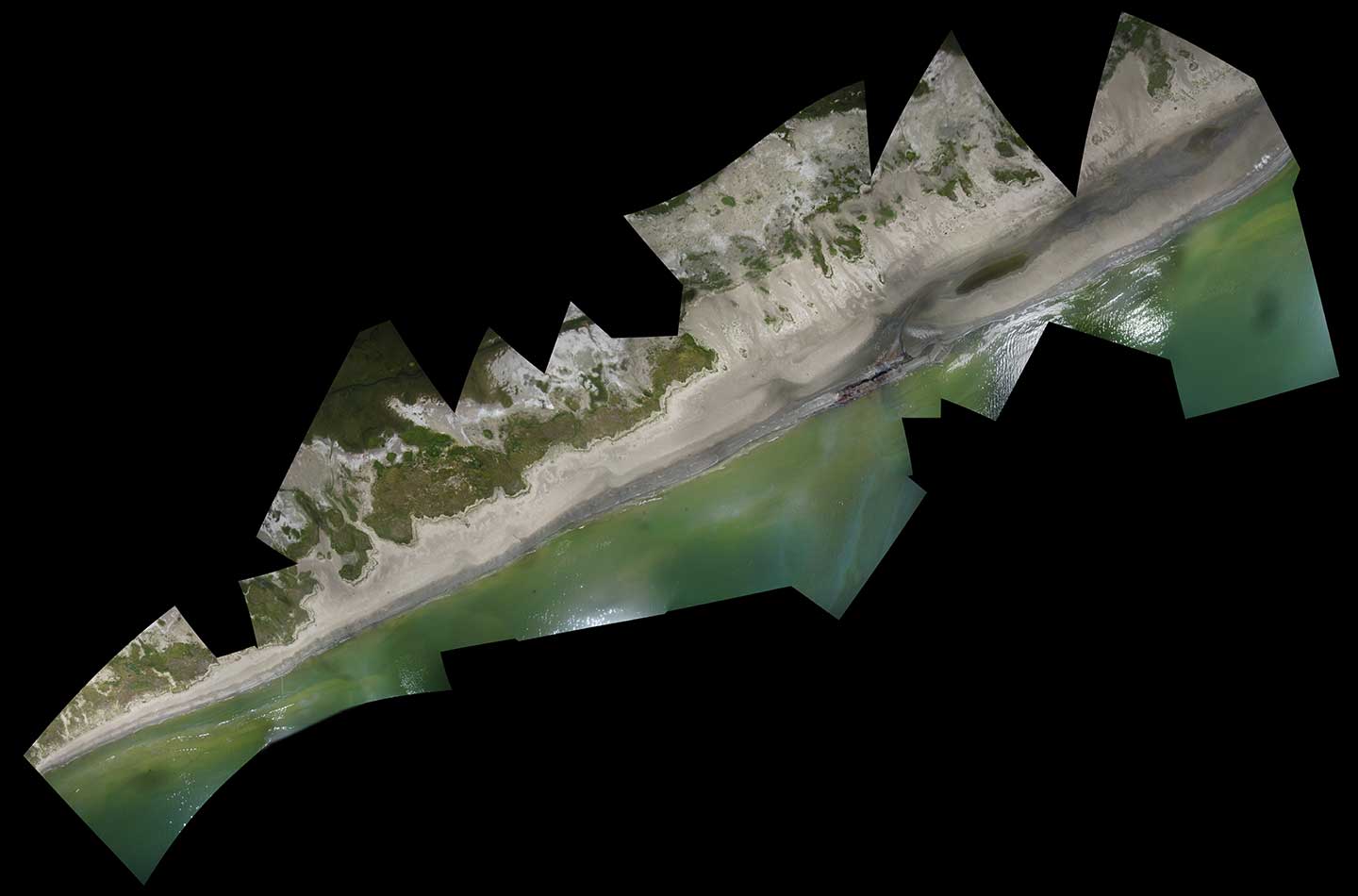

So the two pooled together a diverse group of around 250 community residents ranging from college students to fishermen, training them to strap basic cameras on balloons and kites, go out on boats, and take snapshots of the oil’s progress from the air. In the process, the community-based researchers created what they eventually coined the community satellite. Warren’s project, MapKnitter, stitched tens of thousands of photos together to map almost one hundred miles of coastline, in high resolution and in real time, to reveal what was really taking place on the Gulf Coast.

Soon after the spill, Public Lab began an online forum where anyone could pose a question, add their own research, and reach out to others in addressing local environmental issues on the ground. The site offered no ready-made equipment, but helped provide the tools and kits for communities to build their own devices so that residents were involved in every step of the process—going out into their environments to monitor, interpreting data themselves, and then using it towards political outcomes. Eight years later, Public Lab now helps with community science projects all over the world on a variety of issues surrounding equity and space—from mapping refugee camps in Lebanon to the government relocation of women’s craft markets in Uganda.

A key variable for Public Lab is that communities don’t miss out on the investigation process, that they feel welcome to the entire process of data collection from their initial questions to the evidence stage critical for policy advocacy. What makes Public Lab’s coalition building so inherently powerful is that the key questions they tackle are designed to come straight from the communities themselves, making them the integral voices in the decision-making process. “All of this is really about proper representation,” said Barry.

Dosemagen recalled her early work in Louisiana, when the questions community members were asking drove the kind of research they ultimately ended up undertaking. “The initial moments came from people saying ‘Why do I smell sweet almond? What is that smell?’ There already is a scientific question that’s being asked—sweet almond is the smell of benzene, which is a [pollutant] emitted from refineries,” Dosemagen said. “So I think especially with people that are living these things and know that something is wrong—seeing cancer clusters in their neighborhoods, or watching their children get higher and higher rates of asthma—they want science…to help understand their world.”

With their online store and shippable DIY kits, Public Lab wants to demystify technology by letting people of all ages engage with chips, sensors, and wires without fear. “People have a very strong response to getting their hands on equipment that can help them understand their environment more and help them tell the story of their lived experience more powerfully,” Barry said.

In 2010, not long after Public Lab deployed their first community satellites in Louisiana, the group was contacted by Eymund Diegel, an urban planner in Brooklyn who was concerned about the cleanup of the Gowanus Canal, the infamous toxic-sewage-polluted river that ran through his neighborhood. He was part of a group of canoeing enthusiasts who were brave enough to go on the canal in their spare time, and he was worried the city wasn’t doing enough to figure out the cause of the problem.

“I felt strongly about the neighborhood, and I realized it wasn’t going to happen through the city,” Diegel said, noting how very little government data existed on the pollution of the canal—information on sewage-pipe networks was either averaged out or purposefully withheld from the public. “Issues like these are driven by citizens wanting to reclaim control over their space because they feel government has become too detached, too disconnected from the story of their backyard.”

Since drones and other mapping tools were too expensive, Public Lab’s community-satellite aerial-mapping kits provided a direct connection to the data they needed to prove their case. Eymund enlisted his canoeing club and members from their local conservancy group and swiftly got to work. At first, their setup looked rudimentary—a big red balloon attached to recycled telephone wires, a digital camera modified to take time-lapse photos, and a stabilizing rig made out of a hacked carrot-juice bottle. But the results were striking—the group was able to stitch together high-resolution images showing inflows of sewage, which finally gave them the information they needed to successfully win a Superfund designation for the site despite the city’s initial opposition.

Now Diegel runs many of Public Lab’s community science projects in New York City. The group has also expanded their monitoring efforts in the canal by utilizing a growing number of DIY tools that were first brainstormed on Public Lab’s online portal: water-quality sensors, plant-species phone-tagging inventories, stream-direction dye tracers. But even as the tool kits got more involved and complex, Public Lab still stood by its belief that a shared dialogue between institutional scientists and community members is vital to their discovery process, a keystone of Public Lab’s deep belief in local trust and equitable resource distribution.

“A community organizer that you’re working with probably knows the sites that you’re at better than you will because they’ve been there season after season after season, and they know visually what environmental change looks like,” Dosemagen said. “Whereas you, as a scientist, may be able to tell somebody why that’s happening, you don’t have that same kind of lived experience of being in a place.”

This sharing of knowledge is exactly how Diegel made a huge breakthrough in monitoring the Gowanus Canal. During one of his balloon mapping days, a curious local couple asked Diegel if he knew why an old pump in their basement kept flooding out. Their dialogue led to the discovery of a previously unknown large freshwater stream that they found was being diverted back into the combined sewer system, causing contaminated overflows that pollute the canal. Public Lab’s work helped to expand the EPA’s restoration efforts at the Gowanus Canal. Now it has submitted a plan to divert these clean and natural underground streams to trees and playgrounds in the area to revitalize the community’s landscape and decrease toxic overflows.

For many activists, the government’s perennial lack of investment in local environmental monitoring has only worsened under the Trump administration, but many members of Public Lab see this an opportunity to build even stronger and wider coalitions.

Institutional scientists, used to formal collaborations through federal grants and formalized partnerships, are now increasingly looking towards democratic data-sharing through groups like Public Lab to rethink the ways in which they can actively integrate broader communities into their ranks, methods, and decision-making. Ideally, the process is a dialogue, deeply informed by scientific knowledge, but one that puts lived experience at its very core.

“People are more able to see that we can’t just say science is neutral and just assume that it is. We have to work to make it an equitable place,” Warren said. As more and more scientists are forced into an unprecedented position of defending themselves against political attacks, many are also recognizing a growing and urgent need to completely rethink the role of science and the public’s involvement.

“More and more, we’re seeing people starting to recognize where their work overlaps with other people’s work and to celebrate that rather than to feel competitive. That’s powerful, because there’s a lot for everyone to gain,” said Warren.

In the past year, stronger coalitions between formal scientists and networks of community groups have allowed Public Lab’s DIY tools to scale up beyond localized issues and into other terrains of use.

Public Lab’s newest project—the community microscope—pilots this idea in full force, putting a low-cost technology into the hands of communities so that they can investigate environmental injustices in a bigger and bolder way than ever before. The idea began in 2017 as a community question on air pollution in rural Wisconsin near industrial sites that mined hillsides for sand used in hydraulic-fracking pumps. With roads, backyards, and porches covered in new and frightening dust, locals wanted a method that could measure the changes in their air quality, but they were finding that market-rate equipment racked up costs in the thousands.

Public Lab teamed up with the community to build a microscope that could take pictures of particles as small as 2.5 microns, which are known to cause serious respiratory and health problems when inhaled at high levels. This time, the lab called for coalition building to drive their price point down—and found that the interest in creating this sort of technology spanned geographies and issue groups. Groups against micro plastics, or communities around the world curious about their groundwater quality expressed interest in using the technology to monitor their environment. In June, Public Lab made almost double their initial Kickstarter goal with a kit that costs under $30 and takes just 15 minutes to build.

By transcending the boundaries of political stalemates and elite institutional science, Public Lab continues to show others the way forward: It is proving that a strong, equitable, and diverse community-based coalition can yield national and even global solutions. Ultimately, its approach will be vital in addressing our generation’s most pressing crisis, climate change. What is increasingly missing on a national level is being made up for in a truly revolutionary grassroots way that invites everyone—from socially conscious scientists to technologically empowered communities—to bring their skill set and knowledge to the table.

“The scientific innovations around open source, peer-to-peer research build on our American legacy of grassroots organizing,” Barry said. “I think all of that is going to add up to a better democracy.”