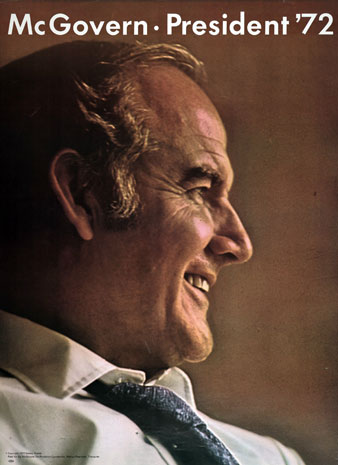

Everett Collection

Everett Collection

A decent man runs a flawed campaign.

To open with a digression:

McGovern is fighting a battle so steeply uphill that it must, at times, seem hopeless . . he has failed to produce any of the results that normally signal the emergence of a major national candidate.

He has attracted none of the traditional power blocs in the Democratic Party. He has precious little labor support….He has no machine support.

Worst of all, he does not appear to have mobilized the people who should constitute his natural following: the liberal Democrats, the poor, the blacks, the young and the body of activists who supported Eugene McCarthy and Robert Kennedy in 1968.

He is running well back in the polls among the Democratic contenders and even Las Vegas oddsmaker Jimmy "the Greek" Snyder figures McGovern a 21-1 shot for the Democratic nomination, lowest on the list except for New York Mayor John Lindsay.

The reasons why McGovern has failed to become a leading—let alone widely supported—candidate are several. Richard Nixon has robbed him of his prime issue, ending the war in Vietnam…most Americans don't think of the war as an issue any more.

Furthermore, though be is very bright McGovern lacks that star quality called charisma . . . he fails to come across where any modern candidate must—on television.

"He says the right things and he has a nice face," says one McGovern aide. But, he adds wistfully, "if only the lucky phrase would come to put him on the front pages with a sharp accent…."

Excuses aside, however, the fact remains that George McGovern hardly seems to have a really good shot at the Democratic nomination.

There, in a typical nationally syndicated news dispatch—or "news analysis"—of December 1971, less than a year ago, is a characteristic assessment of McGovern and his liabilities—the candidate who hasn't fired up the young, the protest candidate when protest is ever so passé, the loser, the long-shot, the also-ran. No labor support, no machine support, no ray of hope from either George Gallup or Jimmy "the Greek." As if this compendium of liabilities weren't depressing enough, the poor bastard hasn't even got charisma.

Seven months later, George McGovern, the Senator from South Dakota, was nominated the Democratic candidate for President of the United States. (And on the first ballot.) Still, this man who may very well be our next President is one of the least known men in public life. It might almost be said that so much has been written about McGovern that we do not know who he is.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

To a devoted reader of the nation's press, George McGovern would appear to have undergone more changes of personality in nine months than the most dedicated habitué of encounter groups. In short order, McGovern the Nice Guy, uncharismatic loser, Protest Candidate, became nationally recognized as the "stalking horse" for Teddy Kennedy. McGovern and his aides spent a lot of time on the road in those early days denying that he was really Teddy Kennedy in disguise. Then, fresh from a victory in Wisconsin, the idealistic loser was metamorphosed before our eyes into something called, collectively, "The McGovern Machine'—a computerized cadre of brilliant young organizers riding triumphantly through the political thickets and trouncing at the polls such naive political newcomers as Edmund Muskie, Hubert Humphrey and John Lindsay. This change can be timed rather precisely. The Loser became the Machine when he (or it) started winning elections.

The Machine reared its head next as an honest-to-God Prairie Populist and, after a few more electoral victories, an Extremist, a radical in sheep's clothing, a spoiler—indeed, a "Goldwater of the Left." He would, said the political analysts, have to "prove himself" (and a cynic might well ask, "To whom?," since all this time he was amassing a healthy winning record at the polls, the traditional way for a candidate to "prove himself").

Soon enough, however, the Also-Ran-Protest-CandidateStalking-Horse-Machine-Radical became "front-running Sen. George McGovern," and with it came a whole new set of personality traits. For now the nice guy with the right ideas of December became the "waffler" of June. No one knew what a "waffler' really was, but nevertheless it was clear to everyone that McGovern was one. And, coincidentally, all the political analysts who were convinced before the first primary that McGovern hadn't a prayer of being nominated were now knocking on the doors of smoke-filled rooms across the nation, searching for any scent they might find of a "Stop McGovern Movement." The press was largely responsible for ballooning anti-McGovern sentiment within the Democratic Party into a Stop McGovern Movement with capital letters.

But McGovern was not to be stopped, and as that became increasingly apparent, the image shifted to "McGovern the Inexorable." He moved into Miami Beach, as the San Francisco Chronicle described him editorially, as "the political John the Baptist with an evangelistic light of reform in his eyes." In its post-convention issue, Time picked up the image, describing McGovern as a man with a "Messianic drive …. In Miami Beach, it was like St. John the Baptist on Collins Avenue." From stalking horse to the Apocalypse in less than 100 days.

The convention brought the McGovern story full circle. The first-ballot victor became once again the predestined loser—this time against Nixon. All those newsmen who had seen- their prophecies shattered in the primaries went double-or-nothing for the general election, describing McGovern (ad nauseam) as a weak candidate with enough Achilles heels to propel a centipede—he lacked labor support (read Meany), old-time Democratic support (read Daley), financial aid (wealthy Wall Streeters), and once again, popular support (read Gallup).

That, broadly, is an accurate portrait of the many McGoverns we have been treated to in the last nine months, but the amazing thing about McGovern's many faces is how widespread the myths became. It is as if some flipped-out media freak periodically threw a rumor into, the puddle of public domain and watched the rippies spread through all the news channels of America. Take for example, the journalistic gymnastics that occurred with the myth of "The Prairie Populist." In Time, Life, Newsweek, the major dailies and on the networks, the public was treated to "in depth analyses" ranging from the sexual interpretation of the Populist psyche to whether or not the movement in Georgia under Tom Watson was more Populist than the Grange movement in Wisconsin or Nebraska under La Follette or Norris. The New York Times Magazine commissioned an eminent historian to trace the development of various Populist trends in American history, supposedly to provide the philosophical basis for McGovern's political stances.

Perhaps the most compelling image was that of organization—what came to be known as the McGovern Machine. This alliterative cliché became, in but a few short weeks, so pervasive that one could be excused for thinking that, McGovern never won a primary—they were all won by the "McGovern Machine." That machine was—depending on whom you read—a phalanx of teeny boppers large enough to people a PTA's collective nightmare; a computerized army of coldblooded young technicians; a tight circle of crafty pros directing a movement of naive youngsters; a cadre of New Leftist "theoreticians"; or a religious crusade—the radicals' answer to Billy Graham.

In trying to find a handy explanation for the primary victories they couldn't understand and hadn't predicted, the political analysts grasped at the "Machine" myth. Looking more closely at McGovern in the early flush of each primary victory, reporters would see first the state apparatus—the "out-front" part o the campaign that was most readily visible—mistake it for the candidate himself, and launch into long "explainers" about why McGovern "really won" this state, resulting in such journalistic drivel as the following:

San Francisco Chronicle: "Fueled on peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, the youthful volunteers were out in force last week as the pre-primary campaigning sputtered towards its penultimate week in New Hampshire."

Joseph Alsop: "Wisconsin and Massachusetts did not in fact prove that McGovern had suddenly developed an irresistible attraction for the American voter. They proved the worth of good organization in primaries."

Newsweek: The McGovern campaigns in New York and California "will involve mobilizing a force so vast that the McGovern campaign may take its place among the major land armies."

Time: "Here was plain, slow-spoken George McGovern, minister's son, prairie populist, leading the armies of commitment and ideological chic. However ruggedly colorless the driver, his bandwagon rolled flamboyantly on, bright with the fresh-faced young and movie stars and intellectuals who had found their new political vehicle."

Where all these accounts broke down was in their failure to note that brilliant organizers and "peanut butter, and jelly" power are for naught without basic electoral support.

The very fact that the state organizations were so broad-based demonstrates that McGovern had the support to begin with. One of Muskie and Humphrey's problems in state after state was that, though they had long lists of endorsements from politicians, they didn't have enough dedicated supporters to finance or staff massive campaign organizations. McGovern had broad support; Humphrey, Lindsay and Muskie didn't.

Going one step further, it could be argued that McGovern's organization was not indeed all that powerful. He had numbers of volunteers and a few novel campaign strategies, but the basic thrust of the campaign was as traditional as peanut butter and jelly. Nor were all those Wunderkinder as brilliant as the McGovern detractors would have us believe. Like any other campaign organization the McGovern camp had its share of superstars with stout egos, some deadwood and a steadily increasing number of opportunists who wanted to latch onto a winner.

McGovern did have broad grass-roots support (and grass-roots money); he did have several devices for getting his volunteers close to the restive voter. And he had one important organizational strategy that was mostly overlooked by the press—let the locals do their own thing. The Washington staff was the smallest possible for a national campaign.

Indeed, the primary campaign's biggest asset was its very absence of organization. That was what allowed McGovern to get closer to the voters, while other candidates sidled closer to the powerless "power brokers." McGovern had a couple of good strategists at the top—not excluding George McGovern—and a mass of enthusiastic, innovative and tireless volunteers at the bottom, with very little managerial organization in between. What looked like a machine to the press was little more than a national "happening."

After the convention, some of the flaws inherent in the "brilliant" primary organization began to surface. Lacking people at the "middle-management" level, it had difficulty functioning as a cohesive multilevel operation. Essentially it was a campaign with a one-track mind—at the very top.

Like McGovern himself to some degree, the campaign was able to handle only one issue at a time. As McGovern had attacked the war or hunger or farm issues in the course of his Senatorial career—but rarely several issues at the same time—so his Presidential campaign suffered from single-mindedness. The staff that had functioned go smoothly when it contested one primary state at a time—concentrating all its resources on that state—seemed to come unraveled when confronted with an unexpected challenge to the California delegation in the Credentials Committee. So the single-minded campaign staff devoted all its time to overcoming the California challenge, thereby scanting the most important decision of all—the choice of a Vice Presidential candidate. That decision—made in about twelve hours—ultimately cost the campaign several precious weeks (not to mention momentum, an aura of candor and desperately needed cash) that should have been spent developing detailed and critical campaign plans.

So the organizational myth tells less about the power of McGovern's organization than about the power of the media priests, who seemed determined to "explain" McGovern's victories without explaining McGovern himself, or the "new electorate" that kept working and voting for him. There are many possible explanations for this journalistic obfuscation, not the least of which is the ties most journalists have with their news sources. There is in this country a political elite that extends far beyond "official" Washington. It includes lobbyists, fat cats, corporate executives, politicians and big-name journalists. All have common lines of communication and interrelated needs.

'The power of a reporter or columnist is dependent, to a large extent, on his contacts with those who actually hold power. And he is tied emotionally and professionally to those with whom he can most easily communicate. One can imagine James Reston dining with Hubert Humphrey at the latter's summer home in Waverly, Minn., and emerging with a week's worth of "insider" column material. It is more difficult to imagine Reston—or for that matter Eric Sevareid, Evans and Novak, Joe Alsop, Max Lerner, Roscoe Drummond or Joe Kraft—dining on their own turf with members of a black caucus, a women's caucus, a Chicano caucus, or indeed with any of the "new power brokers" of the recent Democratic convention. They are outside the personal and informational orbits of these men.

The ties between newsman and news maker are effective information channels when the political alignments of a country maintain an even keel; but at times of political upheaval, of dramatic voter shifts and "new coalitions," the elite reporters and columnists will throw in their lot naturally with the old coalitions—the sources of their information and the sources of their power. Their wisdom will be conventional wisdom; their insights will be dated; their biases will rise to the surface in even the most dispassionate of news commentaries.

Other reportorial errors can be traced directly to candidates who try to sell a particular image of an opponent to the press and the public—the "planted leak." Often the image takes on a life of its own in the netherworld of journalists attached by habit and need to that candidate's camp. Sen. Henry Jackson was one of the first to worry in public about McGovern's "difficulties on amnesty, pot and abortion." Soon the idea gained such wide currency that it managed to outlive the political fortunes of its major proponent.

Newsweek: "Perhaps more important, many Democratic veterans wonder what will happen to McGovern's blossoming blue-collar appeal when Humphrey and Wallace begin drawing attention to his stands in favor of bussing, legalized abortion and eased penalties for marijuana use."

The Los Angeles Times: "The toothache stems from McGovern's positions on a group of ticklish issues, including abortion, amnesty, bussing, tax reform, and his personal attitude toward business."

Time: "Senate Minority Leader Hugh Scott was moved to call McGovern the 'triple-A candidate—acid, amnesty and abortion.'"

Everyone, it seemed, knew of McGovern's "difficulties on amnesty, pot and abortion"—even those who could not state with any accuracy his positions on those questions.

A related kind of conventional wisdom deriving from conventional sources made Edmund Muskie the "Democratic front runner," and McGovern the one-issue "also-ran," more than a year before any citizen had a chance to vote on the question. Muskie was the front runner because the press made him the front runner, and so much for the wisdom of the press.

McGovern's base of support, one that had grown substantially in the Vietnamese War years, was not to be measured by familiar means. His base was outside the traditional political power structure; much of his moncy came in dollar bills through the mail, not from the Wall Street kingmakers; his workers came from homes and colleges and factories, not from machine politicians' master lists; his support derived from the blue-collar worker, not the "labor leaders," from the black man and woman, not the "civil rights leaders"; his ideology grew out of voter frustrations and home-grown dissent, not from the party platforms of years past. The few politicians who looked ahead for clues to the future saw the promise of a McGovern candidacy; those who looked back were wrong.

So the press spun its myths while McGovern got his votes. Some hints of truth lurked within every myth, but the real McGovern continued to elude the merchants of information. Now that the dust has settled a bit, it seems well past time to find out a little more about the Democratic nominee for President.

It is common practice for Congressmen and Senators to send Christmas cards to staff members, friends, contributors and other assorted and important constituents. Usually the inside carries a simple Peace on Earth message, and the cover displays a smiling family photo, a water color of a familiar landmark back home, or a picture of the Capitol. Back in 1962, having just been elected Senator by the whopping majority of 597 votes, McGovern sent out a Yuletide greeting with a picture of the White House on the cover. That is highly unusual—apparently, McGovern had set his sights on the Presidency early in his career. In fact, McGovern once told a reporter that, on Election Day, 1956, as he watched the returns mount in his first political race, he dreamed of running for the Presidency.

The meteoric rise which culminated in the "impossible dream" of 1972 becomes much less a puzzle when one analyzes the early political career of George McGovern. Anyone who took the time to trace his political ascension would have realized that he was not simply Mr. Nice Guy, the White Knight or Saint George. He is and always has been a tough, effective, skillful and ambitious politician, whose outstanding characteristic is dogged persistence. The key to McGovern's success in 1972 is rooted in his experiences as executive secretary of South Dakota's Democratic Party in the mid-fifties. What he did in South Dakota during those lonely and backbreaking years he has now repeated in the most recent four years—only this time his vehicle is the National Democratic Party. The main difference is one of scale, but also the fact that he probably had a tougher job cut out for him in 1952, for the state party then was in worse shape even than the National Democratic Party after the 1968 Presidential campaign.

The WASPish residents of Sioux Falls, Rapid City and Aberdeen who dominate South Dakota politics are very often owners of small businesses, salesmen and bankers—the backbone of the Republican Party. But there are also Germans and Swedes who came to farm the land—and who remain less prosperous than the city folk; they brought with them the prairie radicalism of Wisconsin, Nebraska and Minnesota. It was on the latter constituency that McGovern knew he had to build his base.

From 1936 on, the years had been lean for South Dakota Democrats. And, in particular, 1952 was a disastrous year. The Democrats wound up with only two seats in the Statehouse and none in the State Senate. For the next three years George McGovern crisscrossed the state in his jalopy, trying to build a party organization.

A first priority in breathing life into the party was to organize precinct committeemen and to get candidates for all the offices on the state ballot in 1954. McGovern went to every cake sale, Sunday school picnic and civic function he could possible get to. (Years later, one of his aides remarked that George McGovern had probably shaken the hand of every South Dakotan at least once.) By 1956 he had built enough of an organization and personal following to challenge and defeat an incumbent, Harold Lovre, who had represented the First Congressional District for four terms. McGovern thus became the first Democrat elected to national office in South Dakota since early New Deal days (1934). In 1958 the Democrats elected twenty-one of their candidates to the thirty-five-member State Senate and thirty-two to the South Dakota House. At the same time McGovern was re-elected in a tough fight against the popular, outgoing Governor, Joe Foss. Almost single-handedly, McGovern had built an organization that eventually enabled the Democrats to win the Governor's mansion, both Congressional seats and a Senate seat.

It is difficult to determine just when McGovern made a conscious decision to seek the Presidency. As his deputy campaign manager and former administrative assistant, George Cunningham, tells it: "The Presidential bug was an accumulative bug. McGovern was frustrated as a seminary student. He was frustrated as a college professor—talking to thirty students, reaching maybe fifteen. He was frustrated as a Congressman, one out of 435. He was frustrated as administrator of Food for Peace. He is frustrated as a Senator. It is a bug born of frustration and an inability to achieve what he feels needs to be done in this country."

McGovern had given considerable thought to running for the Presidency in mid-1967. After much soul-searching and a realistic appraisal of his own re-election problems in South Dakota, he suggested to self-styled "President-dumper" Allard Lowenstein that maybe he'd better find someone else to take on Lyndon Johnson—someone like Eugene McCarthy. That decision was to nettle McGovern later, of course, as 1968 unfolded its bizarre and tragic surprises.

The rationale and tone behind a possible McGovern candidacy were laid out in a Look article which greatly impressed McGovern. In the May 28, 1968 issue of the magazine, senior editor, George B. Leonard, wrote: "It may even be possible for some present-day candidate to subvert one of the parties toward openness and encounter. He could start simply by being himself. Even now, anyone who cuts through the sham and scheming, who is entirely honest about his actions, motives and feelings, might well electrify the voters and become a real threat to the pros."

Leonard's analysis reinforced McGovern's perceptions. McGovern had ripened, and it only became a question of time. The tragic assassination of Robert Kennedy, on the night of his victory in the California primary, started the wheels in motion. McGovern did not think that Mccarthy was a winner. He Was a confirmed "Kennedy man," and he was under intense pressure from others in the leaderless and bitter Kennedy following. He campaigned actively for sixteen days and received 146.5 delegate votes in Chicago. Aware that he didn't have a prayer, McGovern got some exposure and set himself up as an alternative leader for the anti-war factions.

The far-sighted responsibility for reform played a major role in McGovern's journey to the nomination. The Democratic Party, and particularly its left wing, was in a shambles after the Chicago convention. Kennedy was dead, Humphrey was a loser, the party was $9 million in debt after the election, and millions of voters felt disenfranchised. McCarthy, with his poetic metaphors and self-defeating ways, was an enigma to his followers, and the puzzlement turned into bitterness when he relinquished his seat on the Foreign Relations Committee (to a hawk) and eventually dropped out of the Senate.

McGovern took advantage of the vacuum by moving ahead on two levels. First, he accepted the appointment by the Democratic National Committee as chairman of the Commission on Party Structure and Delegate Selection. He took the "dead end" task seriously and energetically—much to the astonishment of regular Democrats who learned too late that this was not another exercise in window dressing. McGovern opened the process of convention delegate selection to the disenfranchised. By coincidence, the folks he let in were those who were shut out at Chicago and who were most likely to support him. After nearly two years of tedious deliberation, the McGovern people not only rewrote the rules, they learned them—something his opponents neglected to do. And many of the McGovern commission "whiz kids"—who did the detailed footwork for the commission—were later to resurface as the McGovern campaign "whiz kids."

While McGovern's hands were gaining a firm hold on the party machinery, his legs carried him across the country, beginning in early 1969. He had graduated from the cake sale circuit, but he spoke to anyone else who would listen. He was out to beef up what they call in the pollster trade his "recognition factor," another point that the political heavies missed. While McGovern's position in the polls moved only from 3 to 6 per cent during 1971, his recognition factor jumped from 42 to 72 per cent.

By the time McGovern announced his candidacy on January 18, 1971, that cold winter afternoon in the studio of KELO-TV, Sioux Falls, S.D—an unprecedented twenty-two months before the general election—a careful strategy had been mapped out. He had by that time become the candidate of the anti-war activists and the young. In addition, most of the work of the McGovern commission had been completed. McGovern himself said in October of 1971: "I don't think I would have had the nerve to run for the Presidency if it were not for these reforms."

In essence, then, McGovern had painstakingly built a new house within the Democratic Party, just as he had done nearly a decade ago in South Dakota. The groundwork had been laid for a national campaign at the grassroots level, a campaign like the ones in South Dakota—from the bottom up with carefully chosen constituencies.

McGovern's father, Joseph, decades earlier, had roamed the Plains personally building churches and establishing congregations and then passing on to another town to start anew, leaving behind him a string of established Methodist congregations. So his son set about building a revived Democratic Party—first in South Dakota, then nationally through the party reform rules, and then in state after state the caucuses, conventions and primaries.

As he hit the primary trail—with all the perseverance of the Rev. Joseph McGovern—what was McGovern's strongest appeal? First, he was not a convert to the antiwar movement. McGovern had been against the war since 1963. He came across therefore as a man of deep conviction. He was also open and honest, relatively new, the architect of party reform. And, too, he was "closer to the people"—of necessity, since having been close to the Kennedys he had no real power in Johnson-Humphrey's Washington and had to find his own power base outside the Senate cloakroom. He fit right into the crusader-cum-underdog pattern. In short, he symbolized what America was looking for after all the political duplicity of the Vietnamese War years.

In explaining his appeal, McGovern's supporters describe him as a sort of "anti-politician." Shirley MacLame, for example, could get away with introducing the candidate—to loud cheers at one rally after another in California—by saying, "George McGovern is not a politician but a political humanist."

Some old-line Democrats, as well as reporters of type and tube, indignantly exclaimed that the McGovern people were "new faces practicing the old politics." That may have been true, but new, or old, they were organized, they were close to their constituency, arid they weren't buying a Muskie, a Lindsay or a Humphrey. A week before the Wisconsin primary, Eugene McCarthy wryly remarked of the McGovern operation: "He has got Kennedy staff and McCarthy followers. That's like having German officers and Irish troops."

So the generals and the troops, playing by the new rule book, built a campaign from the bottom up through the primaries. McGovern coolly plied his trade and gathered his delegates and his crucial momentun—just as he had always done—while the press built its sand castles.

The primary campaign went almost exactly as the McGovern strategists had mapped it—slowly, steadily building a delegate majority and popular momentum in a carefully selected combination of primary states. They carefully sank all the bank shots of their choice.

After all the infighting over credentials and platform at Miami Beach, it became obvious to anyone who had listened to him carefully and watched the bargaining of his floor managers that George McGovern was no radical or "Prairie Populist." At worst he was a moderate, and at best a man who seriously wanted to win. It was a point that should have been obvious all along, were it not for the smokescreen put up in the nation's media. McGovern won at the convention not so much because of parliamentary or managerial brilliance but, because he had done his homework—the delegates had come to Miami Beach committed to McGovern and to the changes he represented.

The middle of a campaign is not the time to paint the likeness of any candidate in sharp personal focus, but the outlines of McGovern's personality and style have begun to emerge. His speeches and press conferences tend toward the preacher-teacher style of his early manhood. He employs wit and humor sparingly and doesn't seem very comfortable when he does. His imagination at times seems as flat as the Great Plains, though his speeches often belie that impression. He combines honesty, sensitivity, and deeply felt, convictions with pragmatism and deftness. He seems to be in control of the tensions that exist in a man who consciously attempts to combine idealism with realism. He is, in short, a politician who has his ear to the ground, his sensitivities intact, who wants to win and appears to have enormous talent.

One distinguishing quality about George McGovern deserves special mention. An occupational hazard of most people who enter public life is that they become enamored of their own rhetoric. Hubert Humphrey is an example, in extremis. McGovern is short-winded, direct and economical on the stump. One is struck, too, by the fact that he is a serious listener—another natural asset in a country that has been "oversold" on everything from antacids to Asian wars. The "consumer" is striking back in 1972—he wants to be heard, not told. This rising popular impulse fits hand in glove with McGovern's personal style and political ideology.

McGovern has managed to crystallize the resentments of the voter of 1972. He has symbolized the underdog—the candid voice of dissent—as he has reasoned and preached the inadequacies of current governmental policies. He has symbolized, too, the inadequacies of government by press release. His is a campaign characterized often, but not consistently, by open decision making—"too open" at times for his own political good—and moralistic directness. And he has listened.

This is an ideal formula for winning a limited number of primaries, but it remains to be seen if it is also an adequate springboard from which to win a general election and then to govern. McGovern's attack until now has been more effective politically than administratively. Whether he can translate the primary victories into a successful general election victory, raise his policies to programs, and transform his advisers into governmental managers are still matters for speculation.

The Eagleton affair is perhaps the most striking example of McGovern's administrative immaturity, and McGovern must bear responsibility for it. As a candidate for President he can delegate work, but not responsibility. All the excuses by Gary Hart about not having enough time or people to check out Eagleton are nonsense. McGovern should, at the very least, have spent a couple of hours talking with Eagleton.

By no stretch of the imagination is George McGovern the radical the press painted him—he's not even a Populist, except insofar as he built his campaign close to the people and the issues that he encountered at a grass-roots level. He is otherwise very much the traditional liberal who believes in incremental changes, with power and control flowing from the top. A major problem for McGovern is that although he has a firm grasp of foreign policy and a deep intuitive sense of America's abiding frustrations, he has had little personal experience in dealing with economic and sociala problems, particularly as they affect urban centers and minority groups. Lacking a frame of reference, he has compounded the problem by becoming excessively dependent on academic theorists who tend to spin off their own concoctions, usually with little attention to tough practical solutions. Perhaps after he gets burned a few times—as in the welfare caper—McGovern will shake off some of the awe and reverence he has for academics (of which he is one).

Another problem is his excessive faith in the will and capacity of private enterprise to produce in certain areas of domestic concern, particularly in the critical areas of domestic concern, particularly in the critical areas of job training, rural development and housing. Corporate America has an abysmal record in this regard, and McGovern should be taken to task for his cavalier suggestion that some tax write-offs and a new-found spirit of government-private sector cooperation will do the trick. Some 75 million poor marginal blacks, Chicanos, Indians, Puerto Ricans and whites deserve more than vague allusions to industrial "noblesse oblige" at the taxpayer's expense.

His domestic programs—most of which are still vague—are more or less logical extension of New Frontier-Great Society policies. And, unfortunately, a conventional mind-set refuses to admit that most of those overheralded programs of the 1960s have proved to be failures. Contrary to public relations blarney, Model Cities, Jobs in the Private Sector, Head Start and a host of acronymic programs of the 1960s have not brought garden apartments to the inner cities, an outpouring of employment opportunities from the trade unions or Corporate America, or a renaissance of education in the urban ghettos and barrios.

There is a huge gap in America between the availability and the use of resources. The institutional mechanisms devised by politicians and policed by bureaucrats are simply not delivering quality services. Wether it be in education, health, welfare, law enforcement, transportation, narcotics, housing or any number of other areas, most of our citizens—white and black, poor and middle class—have long since given up hope of improvement. It is for precisely these reasons that George Wallace and George McGovern did so well in the primaries.

The lessons of the last decade are that effective social programs cannot be organized in Washington, at university "think tanks" or in the board rooms of large corporations. They must be organized in local neighborhoods. Only htose local organizations can do the job of combining neighborhood resources and talents with the financial and technical aid of the private sector and government into a coherent and long-term development effort that people can believe in and work for. The inadequacy of incremental gains—when even those occur—is the key to the failure of conventional liberalism, and nothing that George McGovern has said indicates that he is conscious of this underlying issue.

There is no question that the McGovern staff has many highly competent technicians, but where are McGovern's substantive people? It takes an exceptional human being to be both, and until late in September there was little evidence of serious, programmatic content emerging from the McGovern mimeograph machine—at least with regard to issues of race and poverty.

But even though McGovern has been slow to come forth with concrete solutions to pressing domestic needs, he still is in a better position than Nixon. The President, who has had four years to put his programs to work, appears to have given up altogether the search for solutions to urgent social problems. And there are a host of other issues where a McGovern administration would seem heaven-sent next to the Nixon gang. A serious analysis of his administrative decisions, legislative requests and personal biases reveal the President to be the ultimate practitioner of political expedience. Mr. Nixon's public pronouncements on nearly every major issue—unemployment, school bussing, welfare reform, tax reform, prison reform, hunger, black capitalism, the Haynsworth and Carswell nominations to the Supreme Court, the drug problem, abortion the William Calley affair, My Lai, the plight of the POWs, Vietnamization, the bombing of the dikes, revenue sharing, the Manson trial, the India-Pakistan War—are phrased for maximum PR effect and are devoid of serious content. They do not even hint at a sensitive understanding of critical social problems, nor do they suggest the quality of leadership that will bring us closer to their solution. It is not by coincidence that most of Nixon's closest personal advisers are ad agency executives and most of McGovern's are journalists and academicians.

The luckless leaders of the tin-cup brigade (Lockheed, Penn Central, ITT, Boeing, and ever so many more) are far more important to the President than old people on fixed incomes, workers with frozen wages, minority groups or the 6 million children suffering from malnutrition. He wants desperately to be re-elected, and he knows which side of the bread has butter. Big campaign money comes from the vaults of industry and Wall Street; Democratic money traditionally comes from the check-off dollars of wage earners. The best Nixon can offer to the vast majority of Americans is half-truths and, with the help of his ad agency-in-residence, he has elevated their utterance to an art form.

McGovern, by contrast, has opposed Nixon on just about every issue listed above. He senses Nixon's vulnerability both on the issues and on the way he exploits them.

The central thrust of his campaign is, "You can't trust Richard Nixon." Dissatisfaction with Nixon is present just below the surface throughout the country. George Wallace exploited the discontent without a program; McGovern will use it to his advantage with a limited program. He will nourish that discontent through the four central themes of his campaign: an end to the war in Vietnam, tax reform, redirected priorities, and the restoration of trust and truthfulness in government.

George McGovern manifests an almost prophetic (and noncharismatic) sense of the collective dignity and resources of the American people. Whether he can translate abstract attitudes into specific programs is, of course, conjectural. He succeeded in doing just that within the limited arena of the Food for Peace program. On a broader scale, though, he gives the impression that he is a man who has no intention of seeing the country or himself getting clobbered for entertaining a vision.

And one vital factor will serve to "keep him honest." His constituency—however developed—consists largely of those Americans most aggrieved by the problems and dislocations of the "New America." A President cannot move too far from his natural constituency, and in order to maintain his political base, McGovern, as President, would have a mandate to attack the problems of America in innovative and forceful ways. If he did not do so, the consequences could be truly disastrous. Similarly, Nixon, though taking short excursions away from his political home base, has been unwilling to make any dramatic departures from the interests of Corporate America. And, most assuredly, he will be under no compulsion to do so in his final term.

While the press has busied itself putting George MeGovern into old political bags, the man from South Dakota has diligently laid the groundwork for a true "new coalition" within the ruins of the Vietnam-era Democratic Party. Nixon and McGovern both maintain that the American people have a real choice this go-around, and they're no doubt correct. The men are dramatically different in style and substance, in interest and in constituency. Both also agree that Nixon's record is "the issue." It could make a strong case for the challenger.