Why We Should Honor the Chicano Moratorium Against the War

On this date 54 years ago, the largest ethnically focussed action in the movement against the Vietnam War took place—offering an important example of the power of a people united.

Today, August 29, marks the 54th anniversary of the Chicano Moratorium Against the Vietnam War, a march and rally of 25,000 people that took place in East Los Angeles, home to the largest concentration of Chicano/Mexican Americans in the United States. The peaceful march and rally at the moratorium were brutally attacked by an army of 500 Los Angeles sheriffs who assaulted the rally participants with tear gas and billy clubs, injuring scores of Chicanos, arresting about 200 people, and murdering Los Angeles Times journalist Ruben Salazar, Brown Beret medic Lyn Ward, and Brown Beret member Angel Gilberto Diaz. All these victims were unarmed. No sheriffs were ever held criminally liable for this horrendous assault against this peaceful event.

Like many important historical events in the Chicano freedom struggle, the moratorium has largely been ignored by both the mainstream and progressive media and is certainly absent from the history taught in California public schools. This general failure to acknowledge and teach Chicano history is especially important now, as Chicano residents number over 12 million in California and more than 34 million in the entire United States.

While many Chicano activists and leaders remember the brutal assault against the moratorium, we often forget the many important features that also make it such a notable historic event, as part of both Mexican American history and the general history of US progressive movements.

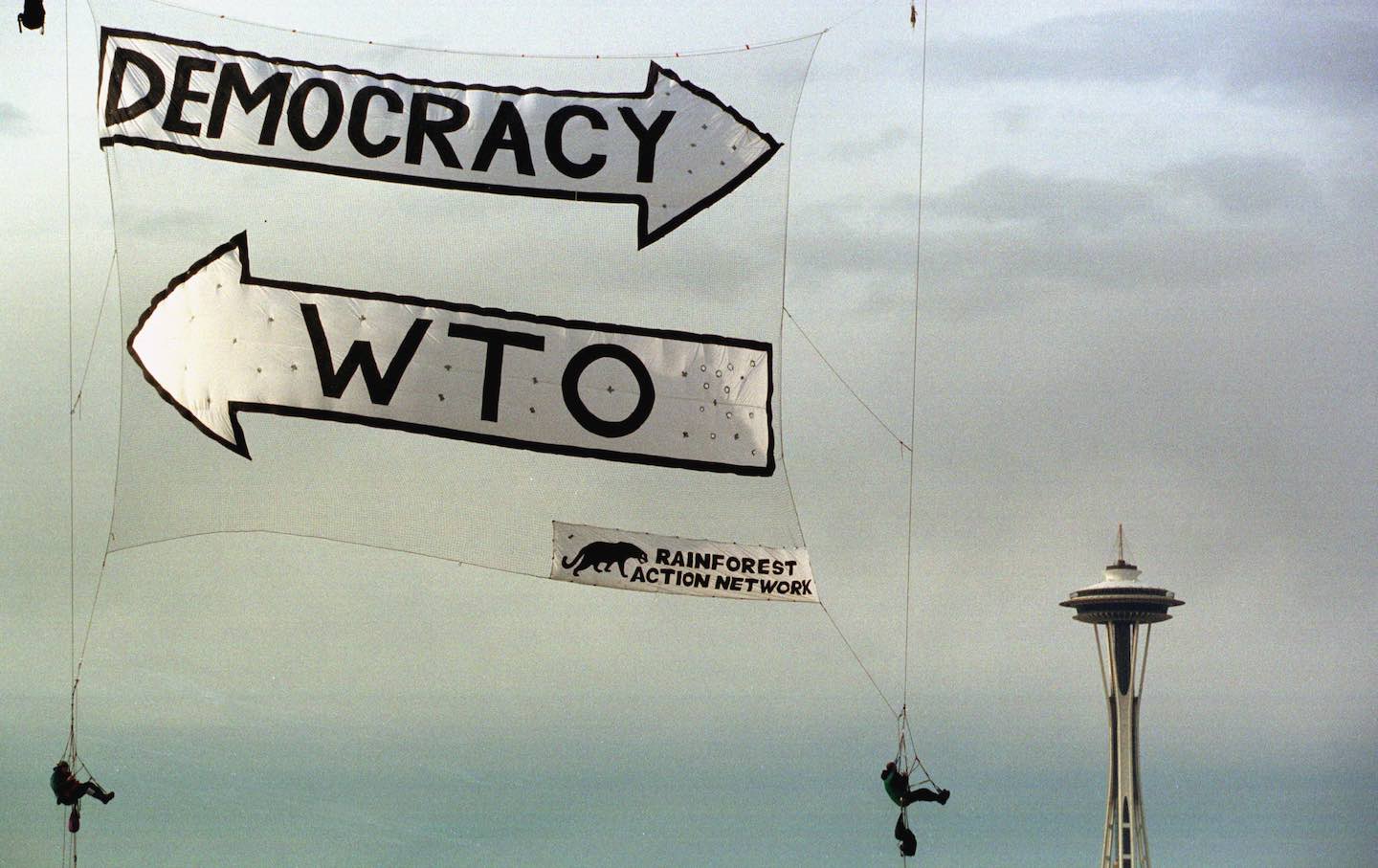

Firstly, it was the largest ethnic-focused anti-war action during the broad and diverse nationwide movement against the US war against Vietnam. While there were several much larger anti-war actions during the late 1960s and early ’70s, this was the first and only action organized and led by a racially oppressed community. In fact, the large moratorium in East Los Angeles was one of 20 such actions that were organized in cities such as Albuquerque, Houston, Denver, Chicago, Douglas, Arizona, and cities throughout California. These events demonstrated the broad and growing Chicano opposition to the US War against Vietnam, a trend that, according to the Henry Kissinger biography The Price of Power, shocked the Nixon White House, which labored under the common illusion that Chicanos were guided by a kind of blind patriotism and conservatism that set them apart from the seemingly more radical Black freedom movement.

Secondly, the moratorium was—at that time—the largest mass mobilization in the history of a resistance movement that began almost immediately after the United States annexed Mexico’s northern territories in the 1840s. Thirdly, the moratorium demonstrated that the younger radical leaders of that movement had a real following among the general Chicano population and were not simply a small group of disaffected youth and students. The East Los Angeles event and other Moratorium actions were organized by the National Chicano Moratorium Committee, which included younger revolutionary nationalists like the Brown Berets and the Colorado-based Crusade for Justice, by members of the Communist Party, and by militant women’s groups like Las Adelitas de Aztlan, with strong support from the radical Black Berets from San Jose, New Mexico.

While the moratorium shared common anti-war movement demands like opposition to the military draft (“Chale Con rl Draft”), it also advanced unique slogans like “Our War is not in Vietnam, it is in our Barrios,” that explicitly connected a strong sentiment of international solidarity with a recognition that our two peoples shared a common oppressor—one who confined us to segregated housing, poor schools, police brutality, low-wage employment, repression of our language and culture, while expecting us to fight their terrible war against the poor agrarian nation of Vietnam. The moratorium highlighted the ironic reality that Chicano troops in Vietnam had among the highest casualty rate among US forces, while suffering double-digit drop out/push out rates in the schools and high rates of mass incarceration, and minimal access to higher education.

Another important feature of the Chicano Moratorium was that it brought together a broad cross section of our community: older and younger generations, businesspeople, professionals, artists and musicians, factory workers and construction workers. But with all of this diversity the Chicano Moratorium was still overwhelmingly made up of workers, participants who were overwhelming representative of our community’s majority—working people who are the foundation of the Los Angeles economy—the second-wealthiest urban economy in the world. The moratorium stands as an example of both the power our community has when it is united and the remarkable political consciousness and courage of our working class.

And lastly, we should never forget that the moratorium had strong support from many other communities: Native Americans, African Americans, Asian-Pacific Islanders, and whites. It demonstrated a true rainbow coalition of support for our resistance movement.

These are just some of the reasons it remains an important holiday of the Chicano freedom movement—one that is commemorated every year in Los Angeles and throughout the Southwest. We can draw many important lessons from this history, lessons that have incredible relevance at a time when Donald Trump and the Republican Party are promising to unleash a massive ethnic cleansing campaign against undocumented immigrants, the great majority of whom live in our communities. Now more than ever, it is essential for our community to unite, to put aside unimportant differences and build a powerful movement that can effectively challenge the fascist danger posed by Trump and his cohorts, and we should center in this movement the voice and leadership of working people, the salt of the earth, who give powerful social resonance to our cry of ¡Si Se Puede!