In New York, a city famous for its historic bridges, one in lower Manhattan escapes notice: a “Bridge of Sighs” at the Manhattan Detention Complex.

Known locally as “the Tombs,” the complex houses male detainees before they face trial. It stands just south of Canal Street, abutted by Columbus Park and surrounded by a cluster of court houses and bail bond shops. The “Tombs” sobriquet predates the current facility, stretching back to an earlier version of the jail: an Egyptian Revival–style building that stood across the street from 1838 to 1902. Resembling an ancient tomb, it was immediately infamous. When Charles Dickens visited in 1842 he concluded with horror, “Such indecent and disgusting dungeons as these cells, would bring disgrace upon the most despotic empire in the world!” Chronically plagued by violence and brutal conditions, the Tombs has been demolished and rebuilt or remodeled four times around its original site.

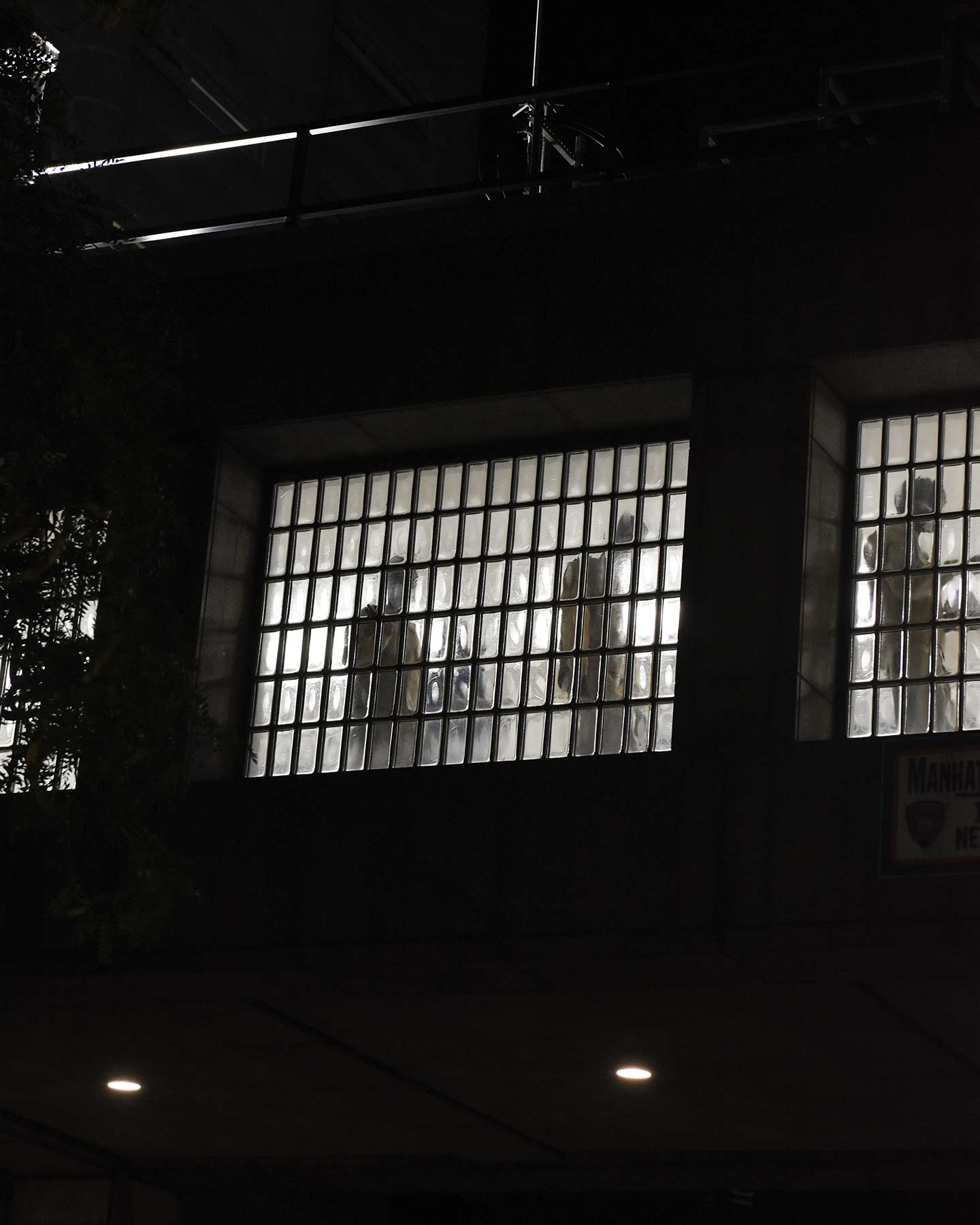

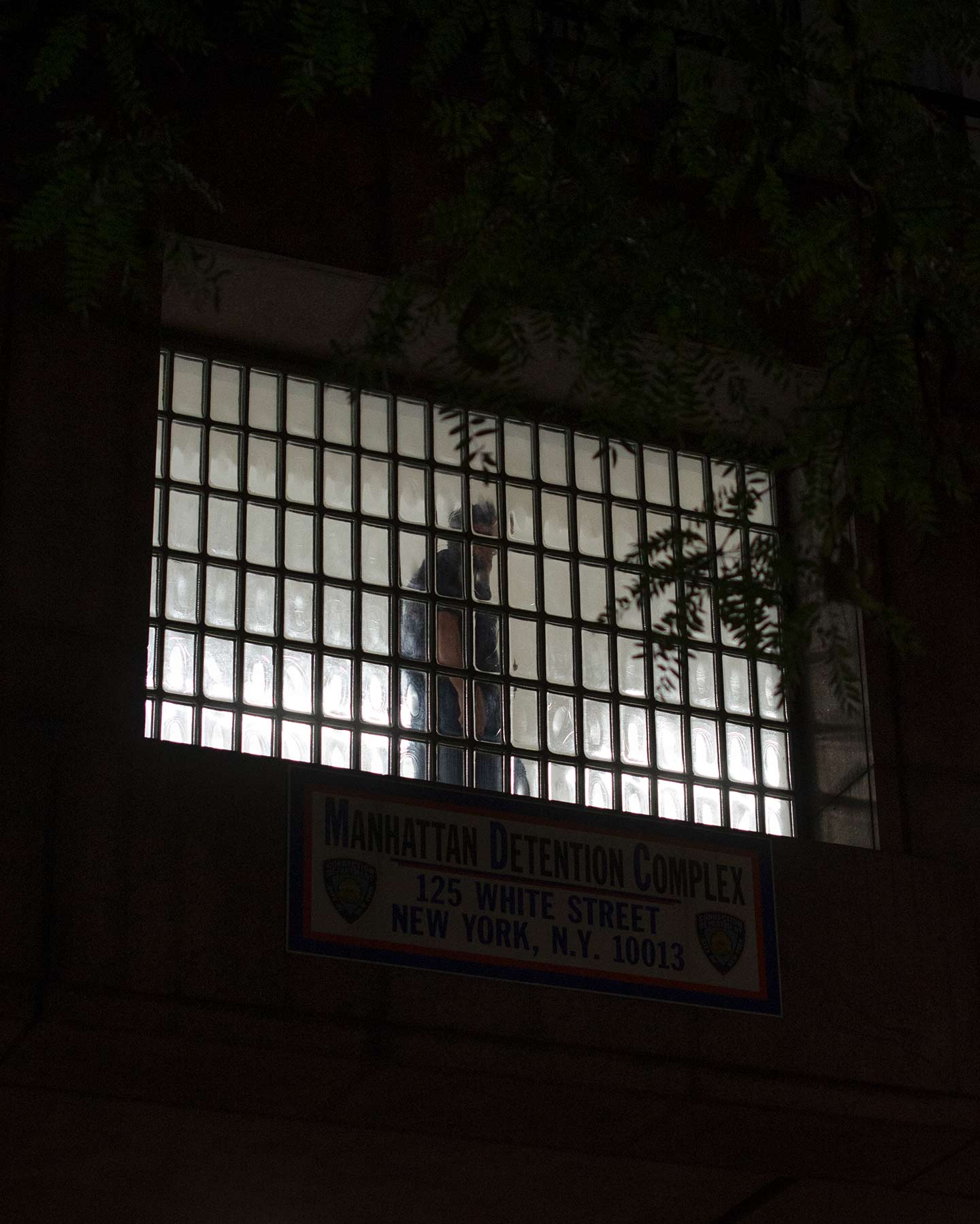

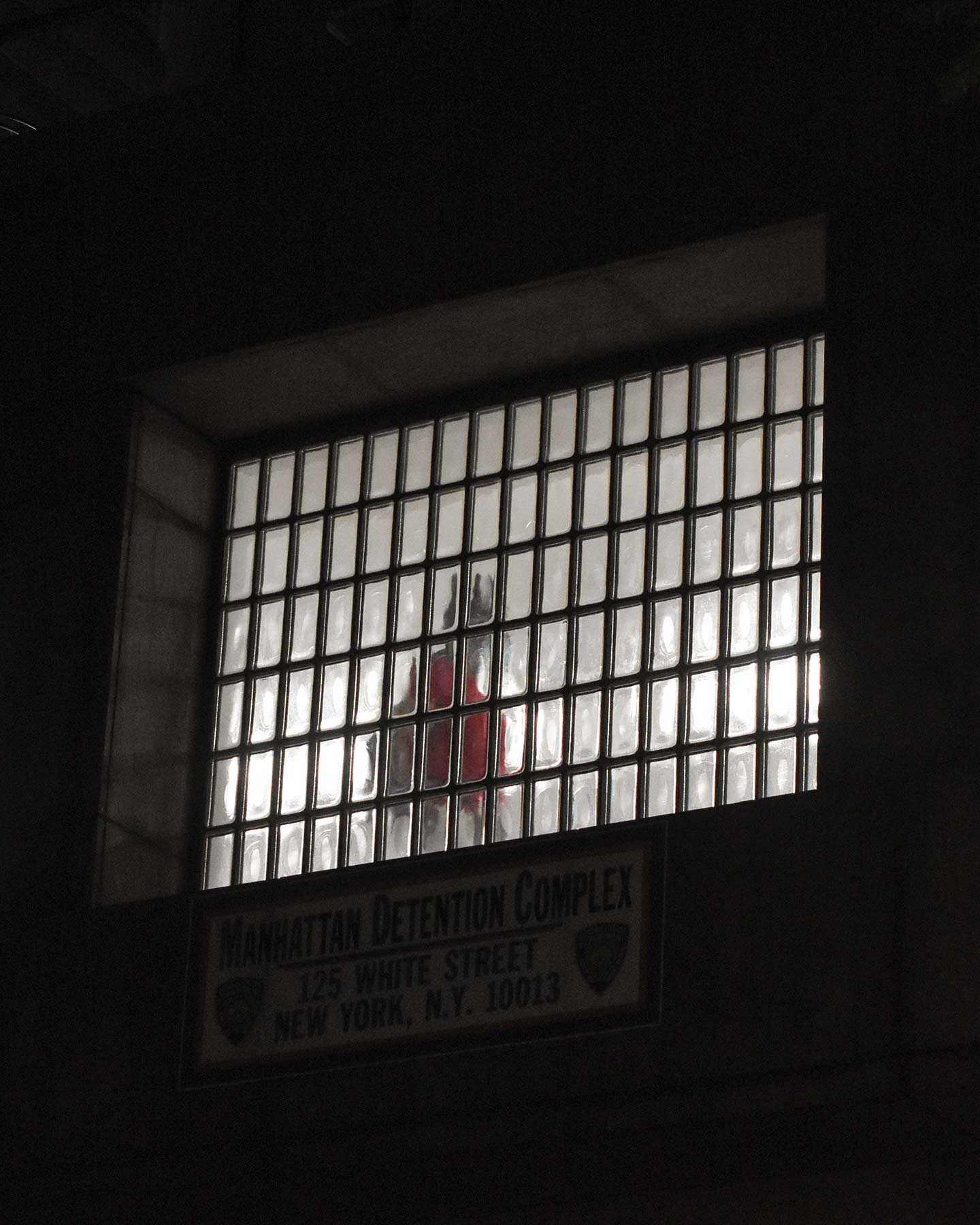

Every version of the Tombs has had a bridge. They’ve served a variety of functions, most infamously to deliver prisoners on death row from their cells to the gallows in the 19th century. Today, a pedestrian bridge spans White Street, joining the Manhattan Detention Complex’s North and South towers. From the street, one can see people crossing the bridge behind thick glass.

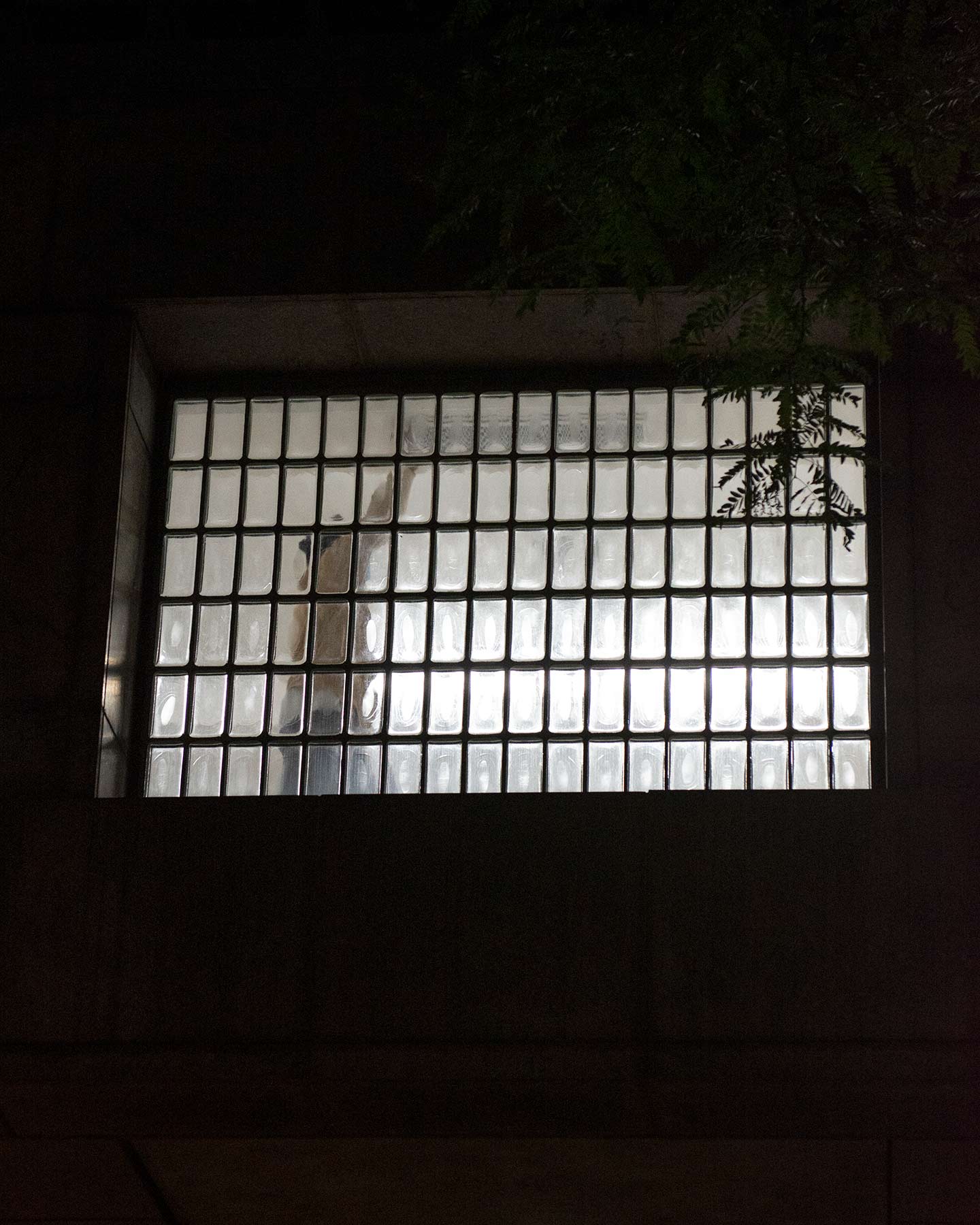

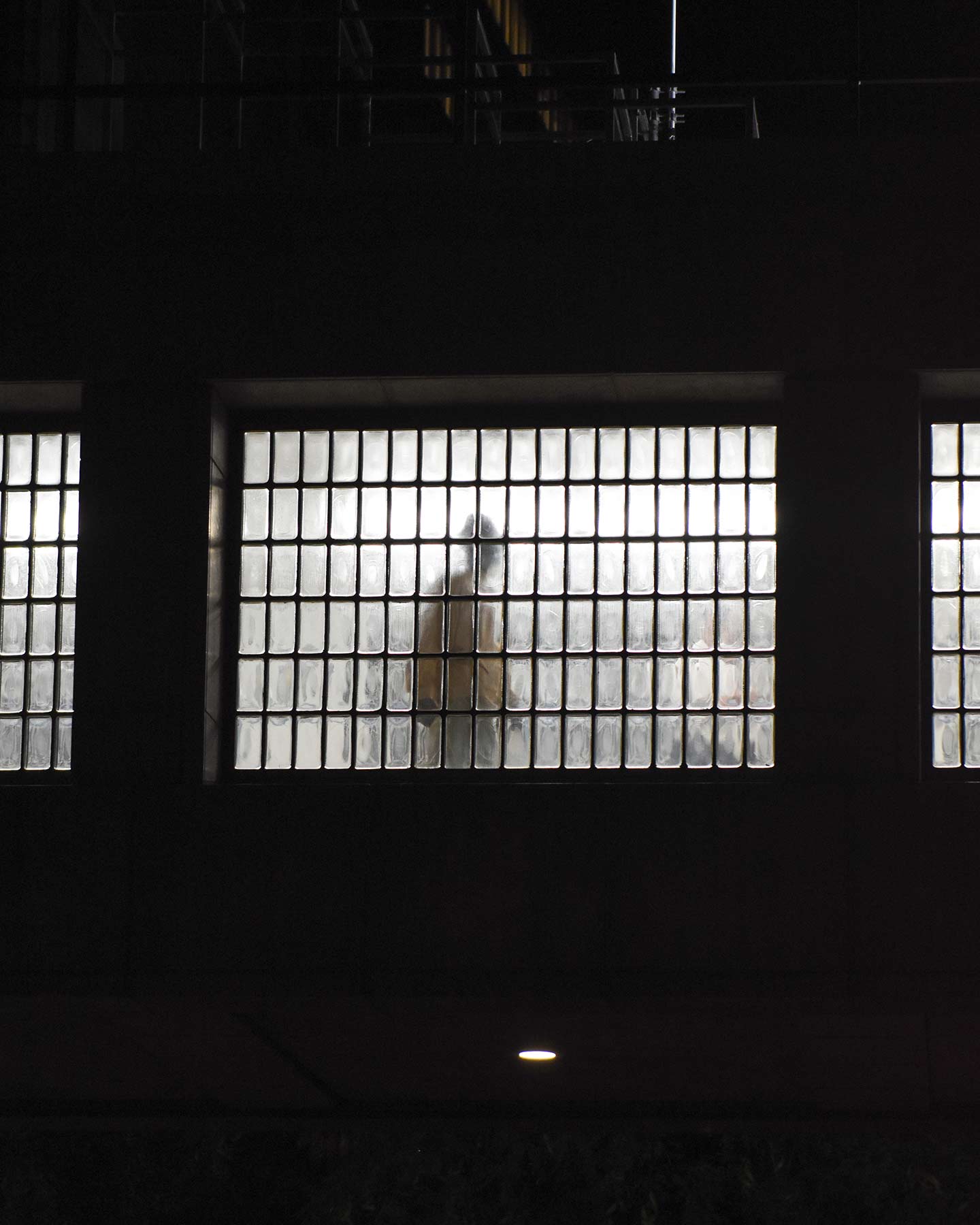

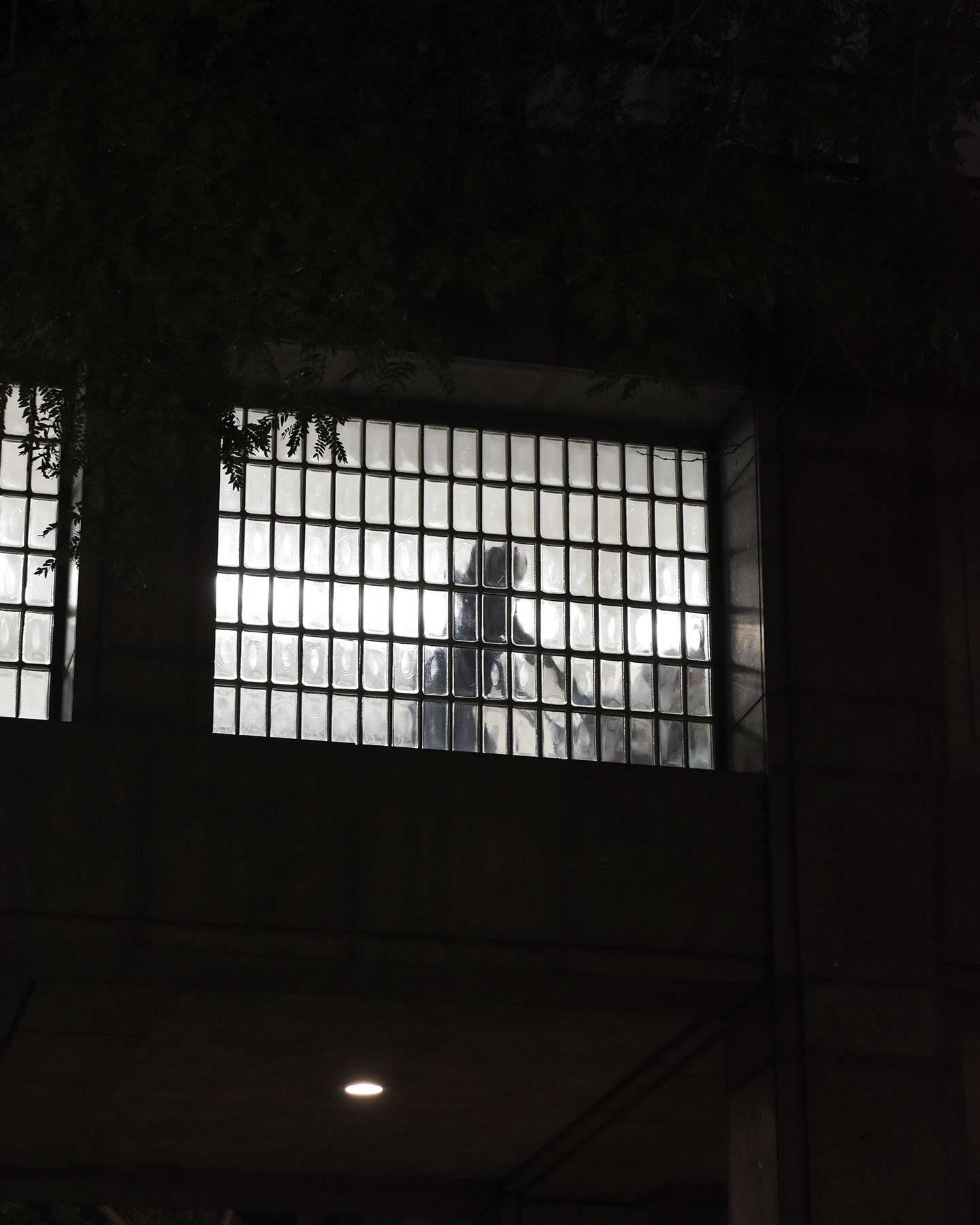

Like the Bureau of Prisons, the NYC Department of Correction goes to great lengths to keep inmates out of sight and mind, particularly during the pandemic, when facilities have been under varying degrees of lockdown. The skybridge is an exception, allowing a fleeting look inside. Figures appear fuzzy and distorted during the day, but when the bridge is illuminated at night, the shadowy forms become clearer. The glass is too distorting to make out details or facial expressions; instead, gaits, gestures and patches of color come into focus. Inmates in tan jumpsuits are escorted across the bridge at half speed, strictly spaced and trailed by a guard in blue. Sometimes they run a hand along the glass or stretch to touch the ceiling. Police and Department of Correction Emergency Service Unit officers cross the bridge casually, unhurried. Nurses in white walk with purpose. A custodian pushing a cart streaks by. Masks in white, black, and pale blue are distinguishable as smudges. The rhythm of the bridge becomes predictable and monotonous, broken only when an inmate looks out the window.