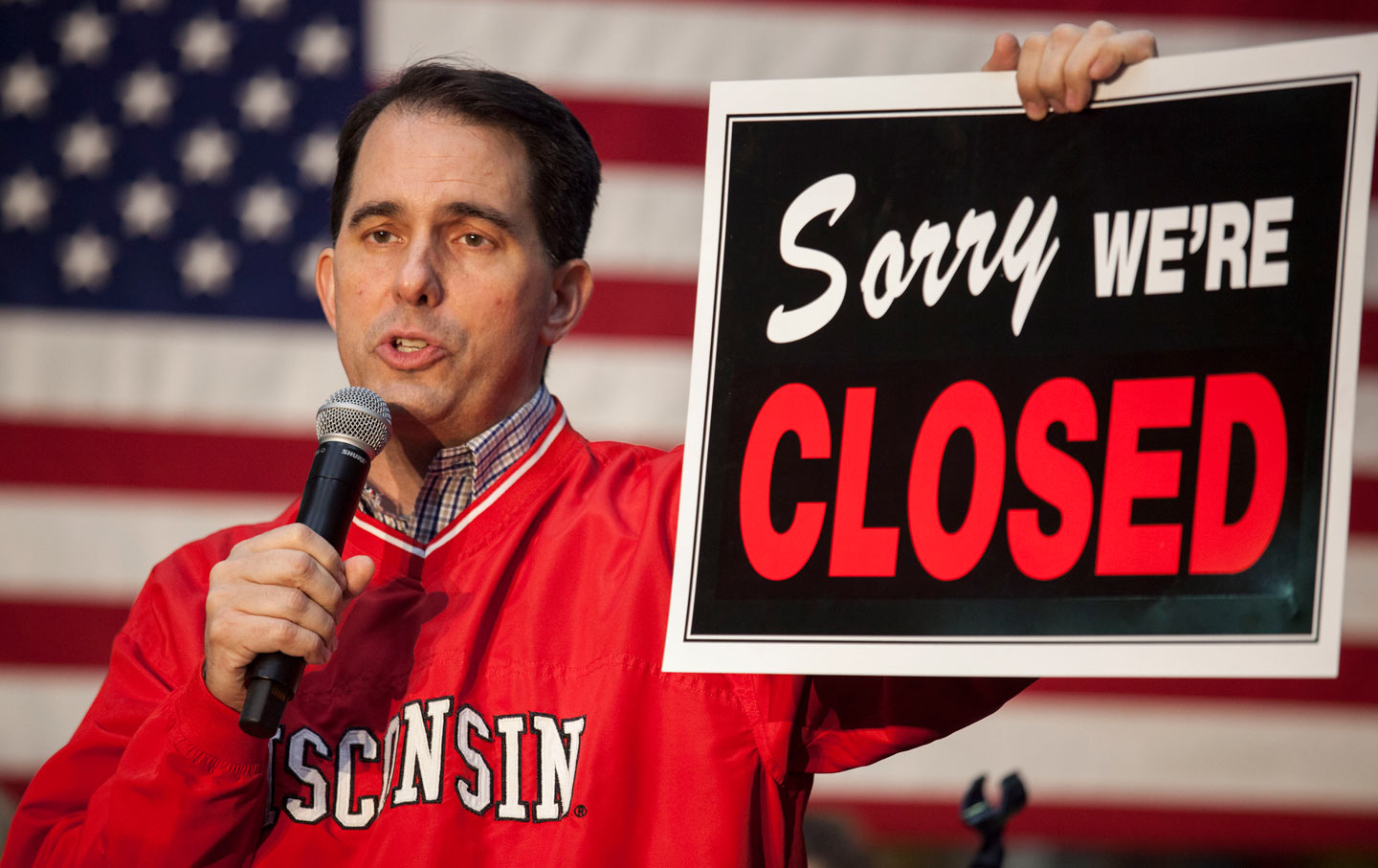

Scott Walker wrote a column for the conservative Washington Times last month, under the headline, “Liberal media and Democrats fan the flames of civil rights ignorance.”

The defeated former governor of Wisconsin warned that “ignorance is dangerous.”

Then Walker proceeded to prove the point—to his own embarrassment.

Walker attempted to claim the mantle of civil rights for the Republican Party by attacking the loathsome Democratic segregationists who wrote and defended racist Jim Crow laws. What the failed 2016 presidential contender neglected to note, however, is that many of the crudest segregationists of the 1950s and 1960s—such as Strom Thurmond, who filibustered against landmark civil rights measures; and Jesse Helms, who campaigned for vile racists and called civil rights campaigners “moral degenerates”—quit the Democratic Party and became Republicans. Why? Because, after Democratic President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the Republican Party lurched right and embraced the cynical “Southern strategy” of Richard Nixon and the divisive “backlash” politics of Ronald Reagan.

As he delved further into his own party’s history, Walker fanned the flames of ignorance into a conflagration that burned up the story of the first Republican campaign for the presidency.

“In my state of Wisconsin, a group of people opposed to slavery came together in a school house on March 20, 1854. They suggested the name Republican for the new anti-slavery party. The first nominating convention was held later that summer in Michigan. Republicans opposed the expansion of slavery into the western territories,” wrote Walker. “Lincoln was the first nominee of the newly formed party. His Emancipation Proclamation freed the slaves.”

Abraham Lincoln was not the first presidential nominee of the Republican Party. That was John Charles Frémont, a considerably more militant figure than Lincoln, who stirred controversy throughout his career as a general and a politician. Campaigning on the slogan “Free Speech, Free Press, Free Soil, Free Men, Frémont and Victory!” the Republican nominee won 11 northern states in the election of 1856, including Wisconsin, but lost to Democrat James Buchanan.

At the start of the Civil War, as a Union Army major general and commander of the Department of the West, Frémont aligned with so-called “Radical Republicans” and, in August 1861, issued an unauthorized order emancipating the slaves of Confederate allies in Missouri. Lincoln, who would not issue his own Emancipation Proclamation until a year later, annulled Frémont’s order and the general was eventually relieved of his command. Frémont made no apologies. He remained an unwavering abolitionist, declaring, “There must be no cessation nor rest until Slavery is extirpated to the last root.”