Unfortunately for Donald Trump, I’m Not His Alibi

Trump’s lawyers are bizarrely trying to link me (yes, me) to January 6. It’s a sign that the former president’s case is less than airtight.

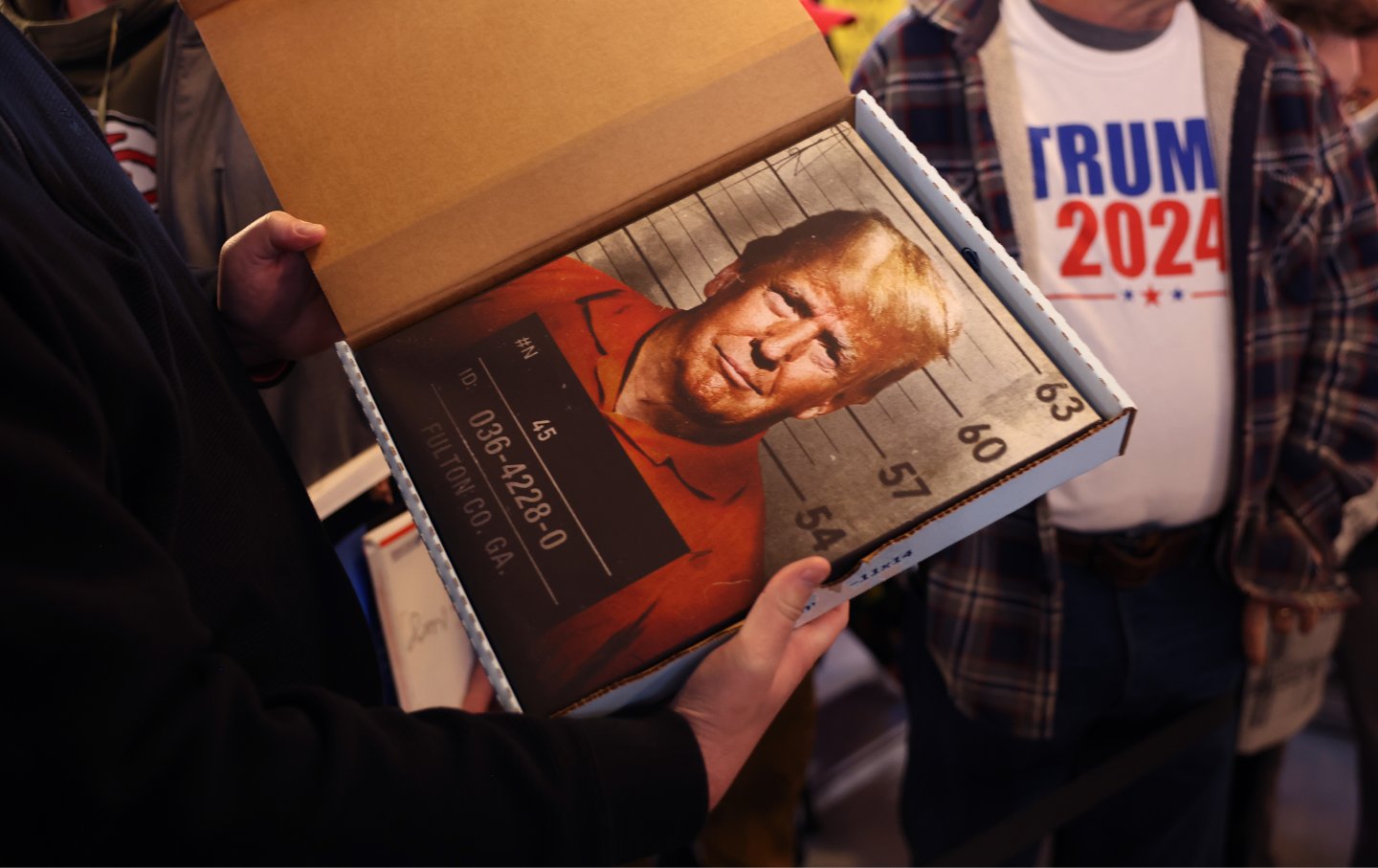

A supporter holds a print depicting Donald Trump’s mug shot as he waits for him to arrive at the Whiskey River bar on December 2, 2023, in Ankeny, Iowa.

(Scott Olson / Getty Images)Every American who is charged with a crime has the right to mount a robust defense. That includes Donald Trump. Unfortunately, Trump’s attempt to defend himself from charges brought by special counsel Jack Smith in relation to his efforts to nullify the results of the 2020 election has taken a surreal turn.

In discovery documents filed in late November, Trump’s lawyers revealed that the former president is apparently building his defense based on Internet conspiracy theories, including one involving… me.

The Washington Post reported Tuesday: “In court filings last week, the former president revealed that he has been pressing the Justice Department for information on far-right claims often elevated in his speeches, on his social media feeds and by his conservative allies in Congress—further blurring the line between his campaign and his court battles.”

A letter from Trump’s lawyers to the Justice Department makes dozens of requests for documents relating to actions by “foreign actors, whether state or non-state, to ‘undermine public faith in the U.S. democratic process,’” “Antifa or persons or persons associated with law enforcement who encouraged or participated in any illegal activities on January 6,” “communications between [acting chief of the United States Capitol Police] Yogananda Pittman and Nancy Pelosi, Nancy Pelosi’s staff, or representative of Nancy Pelosi,” and “John Nichols, or any similar persons who encouraged or participated in any illegal activities on January 6th.” The Post’s piece explains that the last reference is not to some other John Nichols but to “a liberal journalist in Wisconsin.”

I can’t speak for Pelosi, but I have to think that my inclusion on this list, as someone who wasn’t anywhere near the US Capitol, or even Washington, D.C., on January 6, is a sign that the former president’s case is less than airtight.

What’s going on? As part of the effort to defend Trump’s actions leading up to the January 6 insurrection at the Capitol, the likely 2024 Republican presidential nominee and his allies have intimated that federal agents and/or bad actors—presumably associated with “the deep state”—provoked trouble that day. These arguments have failed to gain traction even with many Republicans, because they frequently defy logic.

For instance, I’m a particularly odd person to associate with the intelligence community, “deep” or otherwise, as I’ve written extensively about the importance of preserving privacy rights in an era of mass surveillance, and I have argued against efforts to punish Julian Assange and Edward Snowden for revealing details of government wrongdoing. But, apparently, some of the more conspiracy-minded Trump supporters invented a scenario in which I was in D.C. on January 6 as an agent provocateur who climbed a scaffold outside the Capitol and urged protesters to move toward the building.

On top of that, as someone who has done hundreds of cable news interviews—including several on Tucker Carlson’s old Fox News show—I’m not sure it makes much sense to suggest that I could have anonymously blended in with the hyper-political crowd that surrounded the Capitol on January 6.

But common sense does not always prevail.

I first heard about this particular conspiracy theory a little over a year ago, from Caitlin Graf, who does publicity for The Nation. She sent over an online post that compared an old picture of me—from long before I got bifocals—with that of an alleged protester. The argument was that we might be the same person because we had similar glasses and facial features. I didn’t know if the picture of the protester was legitimate, or if I have a doppelgänger. But I certainly knew that I hadn’t been at the Capitol that day. So did Caitlin and other folks at The Nation who had helped edit and amplify the journalism that our staff produced on one of the busiest days in the magazine’s history.

I sent a DM to the person who was speculating about me and explained I wasn’t in DC on the 6th. He responded politely, saying he’d note my clarification, and I didn’t hear much more about the matter. Things would show up on Twitter now and again. But the references were rare and seemingly inconsequential. So that was that.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Until the other day, when I got a call from Rachel Weiner, an able reporter for the Post who was following Trump’s D.C. case and had found the reference to me in the paperwork filed by his lawyers. I didn’t know how it got there, but I was delighted to talk about what I was doing on January 6, 2021.

To clear up any confusion on the part of the former president or his lawyers, I was in Madison, Wis., the city where I’ve written about politics for The Nation for the past two decades. That morning, I was up early to check on the final results from the Georgia runoff elections that gave Democrats control of the US Senate. That was a big story but, as someone who had written a book on the contested election of 2000, along with dozens of articles on the Electoral College and the arcane processes by which the votes that choose the president are counted, I was also excited to settle in and watch C-SPAN’s coverage of the congressional review of the electoral votes from across the country. But first I had to take my daughter to the orthodontist on the east side of Madison. That meant I missed Trump’s rally on the Ellipse, but I wasn’t bothered by that; I hadn’t expected that it would turn into such a big deal.

By the time I got home, it was almost noon in Madison, and the count, with all its pomp and circumstance, was beginning. Like most Americans, I was initially confused when the process was interrupted and Vice President Mike Pence and members of Congress were swept out of the room. But it quickly became clear that this was not going to be a traditional review of reports from the states.

My first instinct was to start calling people in D.C. I had a long conversation with US Representative Mark Pocan (D-Wis.) who was in his office on Capitol Hill. Once we’d established that he was safe and could talk, we reviewed what had happened so far. By then, Pocan and I both knew the basics of what had happened and were already talking about potential consequences. I’ve written several books dealing with presidential accountability, including a popular history of the impeachment process, so I was interested in whether House members were talking about holding Trump to account for inciting an insurrection in the last days of his presidency. I got my answer quickly. Newly elected US Representative Mondaire Jones (D-N.Y.) called for impeachment within minutes of the disruption of the count, and not long after that US Representative Ilhan Omar (D-Minn.) signaled that she would be drawing up articles of impeachment. At about 1:30 my time, I reached out to US Representative Ro Khanna (D-Calif.), who was sheltering in the Cannon House Office Building, and it became clear to me that members of Congress were already weighing questions of whether to censure or impeach, or perhaps encourage Trump’s cabinet to invoke 25th Amendment’s provisions for removing presidents.

I pulled together the information I had gathered, started writing, and got a story filed to my then-editor, Anna Hiatt, by mid-afternoon. I also fit in an interview on Jeff Santos’s syndicated radio show and various other media conversations. And I joined fellow Nation writers and editor Don Guttenplan in filing short takes for The Nation’s live blog, which Jeet Heer had pulled together.

What I had to say that day about Donald Trump was tough, and it got tougher. In my columns, I wrote extensively about the impeachment power and other accountability tools. That probably didn’t make Trump or his most ardent backers view me in a favorable light, which some folks have assumed is why Trump loyalists turned their attention to me. I don’t know. But what I do know is that this is part of a very serious issue we face as a nation.

There’s a growing tendency, by folks on the right and the left, to assume that people they disagree with are always out to wreck their rivals. In addition to harming the basic workings of democracy—which require us to respect that Americans can hold radically different views and still have faith in the process—this theory narrows political discourse in a way that undermines the development of the broad coalitions that have always been needed to challenge political and corporate elites in general, and the intelligence community and the military-industrial complex in particular.

For decades, I’ve written about people from across the political spectrum who seek to build those coalitions, including conservative and libertarian-leaning Republicans, such as Rand Paul and Justin Amash, who have defended privacy rights and challenged the military-industrial complex. I’ll keep doing so, with the faith that people can disagree without despising or distrusting one another. I’d like to think that Donald Trump might even come to that conclusion, and if he did I’d be more than ready to write about it. Unfortunately for the former president, however, I’m not ready to be his alibi.

More from The Nation

Democrats Are Overdue for New Leadership Democrats Are Overdue for New Leadership

To mount an opposition under the coming Trump administration, the party needs new ideas—not the same establishment clinging to power.

Why Democrats Are Losing Americans Without a College Degree—and How to Win Them Back Why Democrats Are Losing Americans Without a College Degree—and How to Win Them Back

Voters intuitively know that the economy has not worked well for most of us for decades. Democrats must offer them a transformative vision, and stick to it for as long as it takes...