The Age of Rage: Protest, Camera, Action

Photography radically acts as a language that speaks for the world’s oppressed and critically functions as a vital visual voice of resistance.

This essay is excerpted from Flashpoint! Protest Photography in Print, 1950–Present (release date: November 2024), an anthology that presents a global selection of photo books, zines, posters, pamphlets, independent journals and alternative newspapers that address the use of photography in protest and resistance from 1950 to the present. Edited by Russet Lederman and Olga Yatskevitch, Flashpoint! can be preordered here.

The dawning of the “Age of Rage”—anger at denied social and political agency for marginalized peoples—appears as an undeniable presence in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War. However, the “Age of Promise,” liberation for all, that was heralded by the defeat of the Axis powers, was not forthcoming. The contributions, for example, made by people of color and women workers of the world were quickly negated and erased from the dominant narrative of how the Second World War was won. Colonializing patriarchal ideologies, local and global, were rearmed and reset for the return of a desired state of Eurocentric white male global dominance. The status quo of life before the war was reimagined. However, new frontiers of resistance to the old regimes of dominance were opening all over the colonized world as fights for women’s rights, sexual freedoms and better conditions for the working class. The implementation of human rights for all marked the following decades as turbulent and contested times that were framed by the threat of nuclear war and paranoid, brutal Cold War politics.

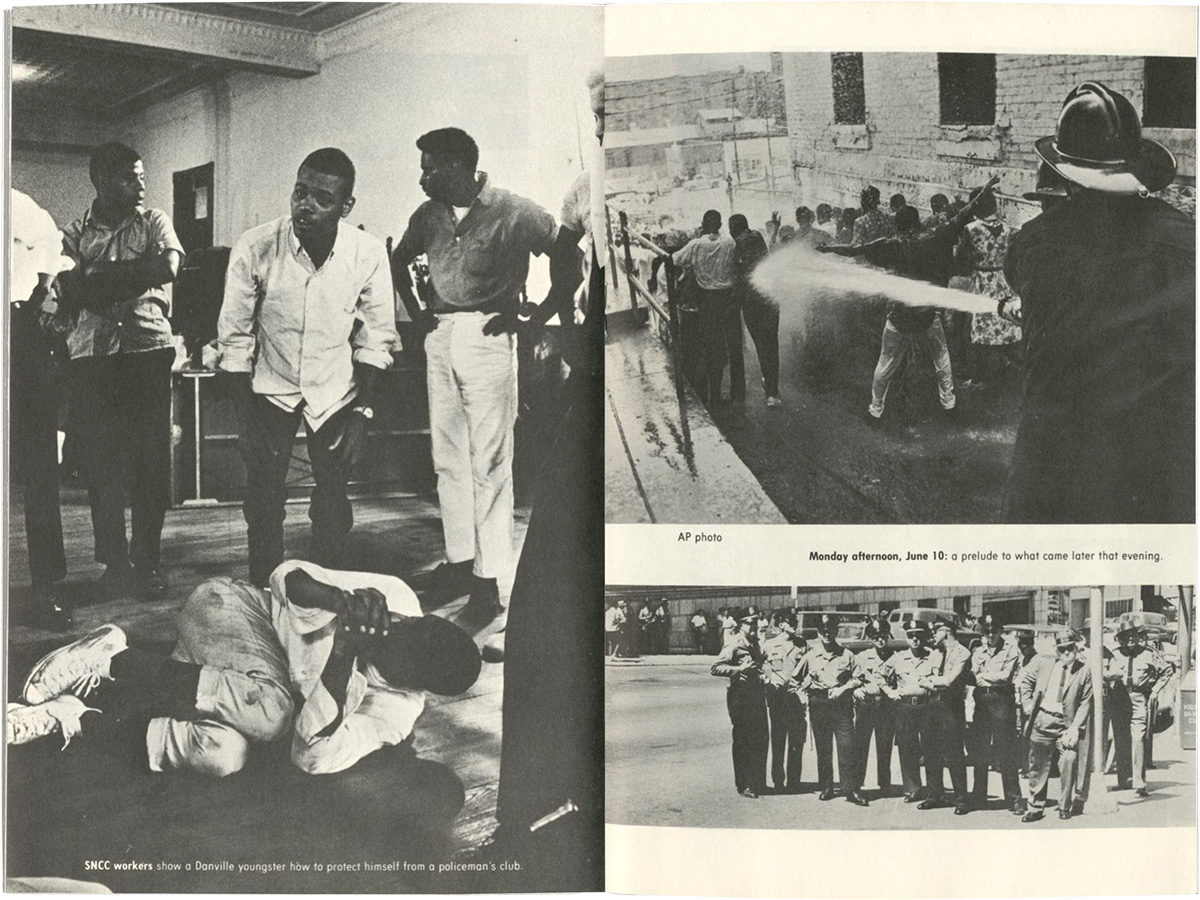

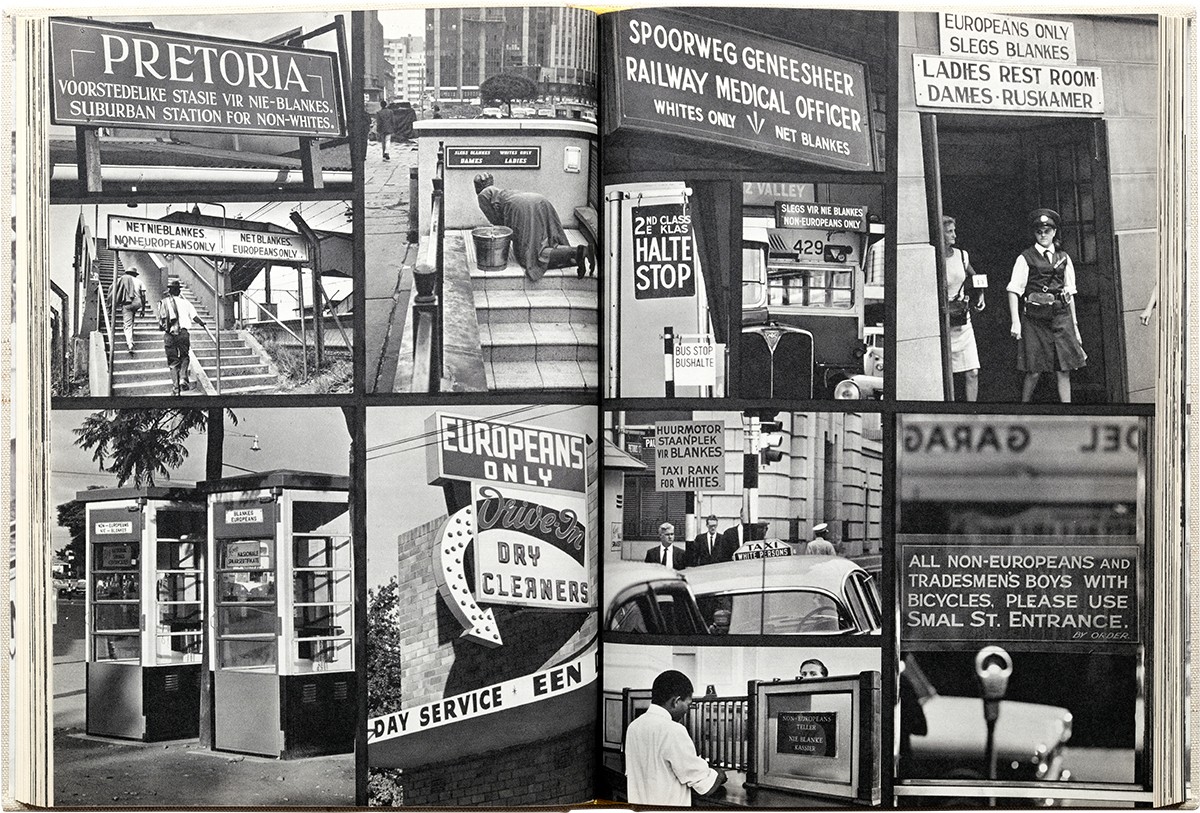

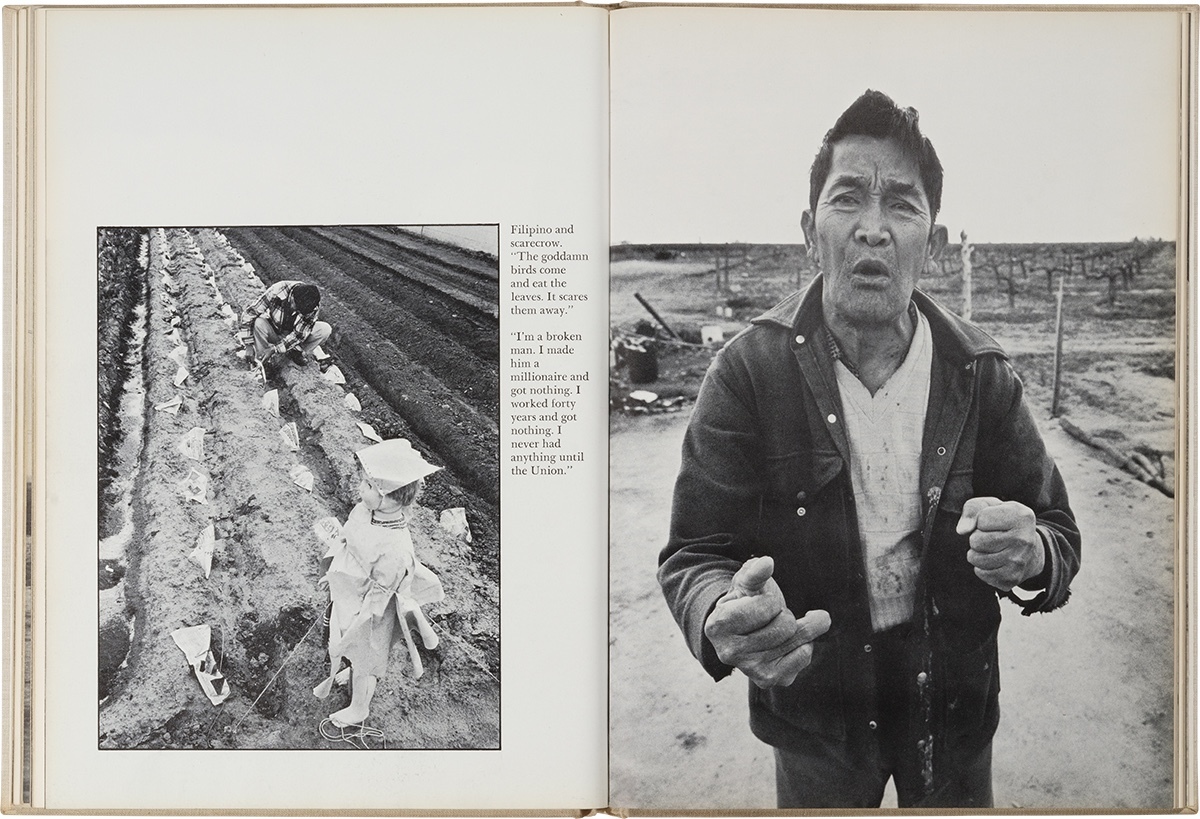

Power concedes nothing, and the fight for freedom for those historically denied political agency remains an ongoing struggle. How else can we understand the brutality of state violence where innocent citizens are imprisoned or killed with impunity? Photography, especially images that focus on the injustices of the world, radically acts as a language that speaks for the world’s oppressed and critically functions as a vital visual voice of resistance.

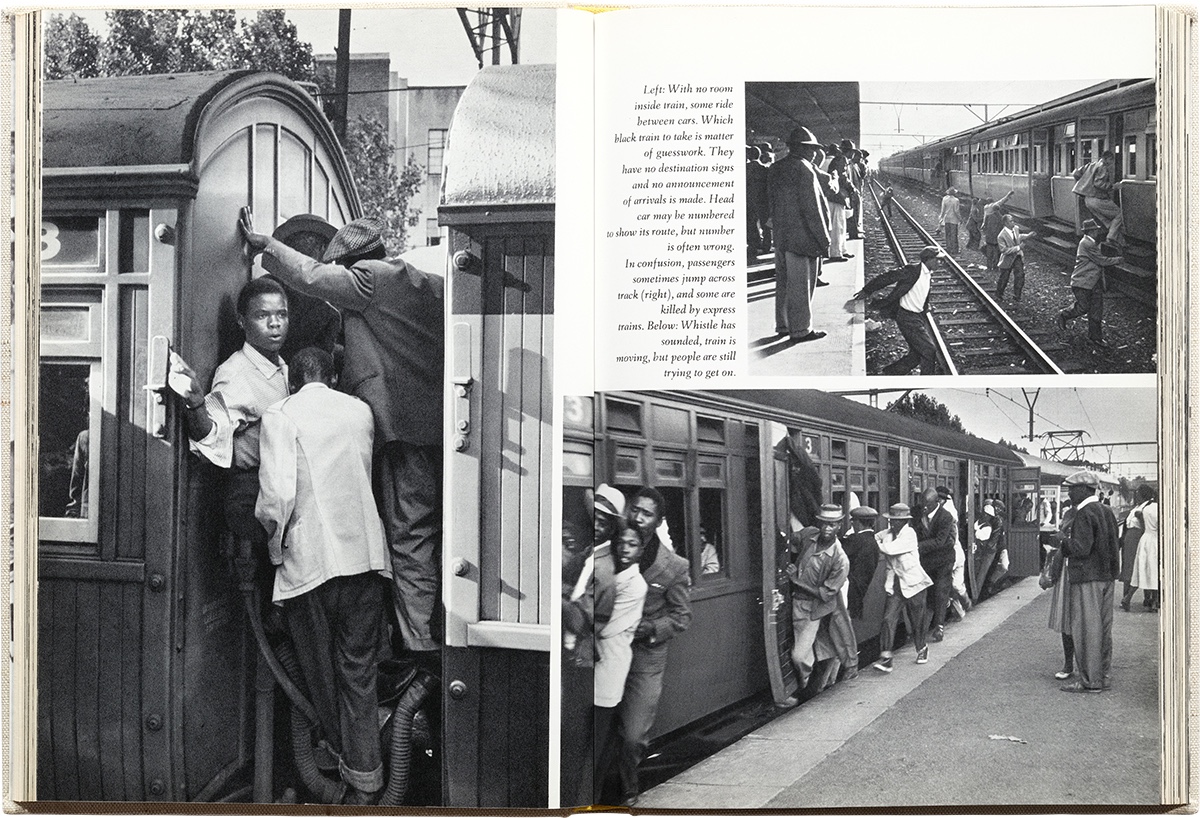

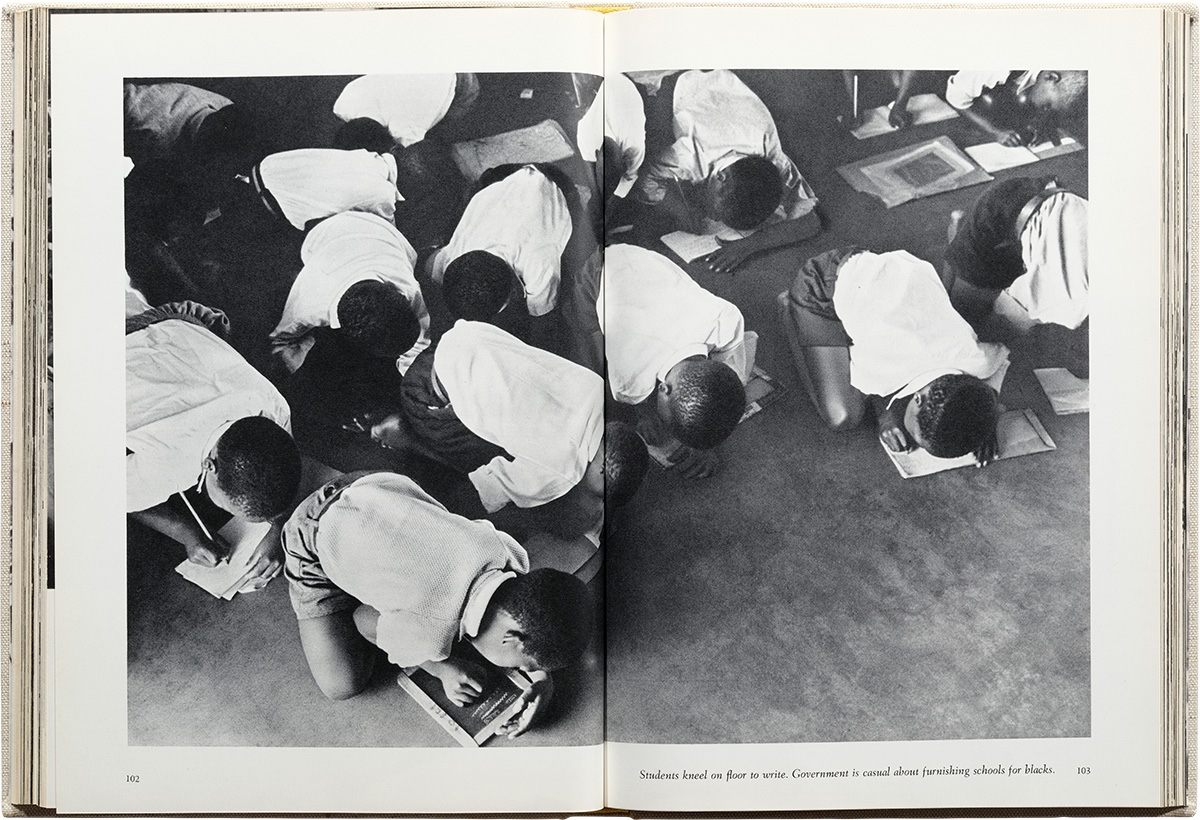

Photography helps us understand what we are and imagine what we might become. It is why, for example, photographs taken to document and support the fight for civil rights in America and the struggles against South Africa’s apartheid regime remain such potent visual symbols. Images made within the Age of Rage are critical punctuation marks across the power structures that resist equality for all.

Every photograph of a broken, innocent body proclaims our lack of civilizational progress. It is vital that we honor images of resistance, knowing that in the future, they will be increasingly challenging to produce as we move toward and navigate the politics of the artificial visual world.

By their very virtue, photographs made in the Age of Rage work against the grain of violent regimes and their myriad forms of social injustice. They remind us that an alternative reality is possible. Photographs of resistance hold those who abuse power to account. Ernest Withers instinctively understood this when in 1955, he took the now-iconic photograph that appears in his self-published booklet, Complete Photo Story of Till Murder Case (1955), of the Reverend Moses Wright, a 64-year-old, five-foot-three Black man who took the witness stand in a Mississippi courtroom, pointed his finger at J.W. Milam, one of the two men accused of murdering Emmett Till, and said, “There he is.” Justice may not be immediate, but through photographs of resistance, it lies patiently waiting to do its duty in time. Politically, every image made that works as a symbol of protest oppression resides within the image bank of justice, held on account, waiting to be drawn down, to serve when required as a reminder that all freedoms must be defended. Reverend Wright knew full well that as he raised his hand and pointed his finger, his life from that moment on was in severe danger, but his act of defiance through the lens of Withers lives on.

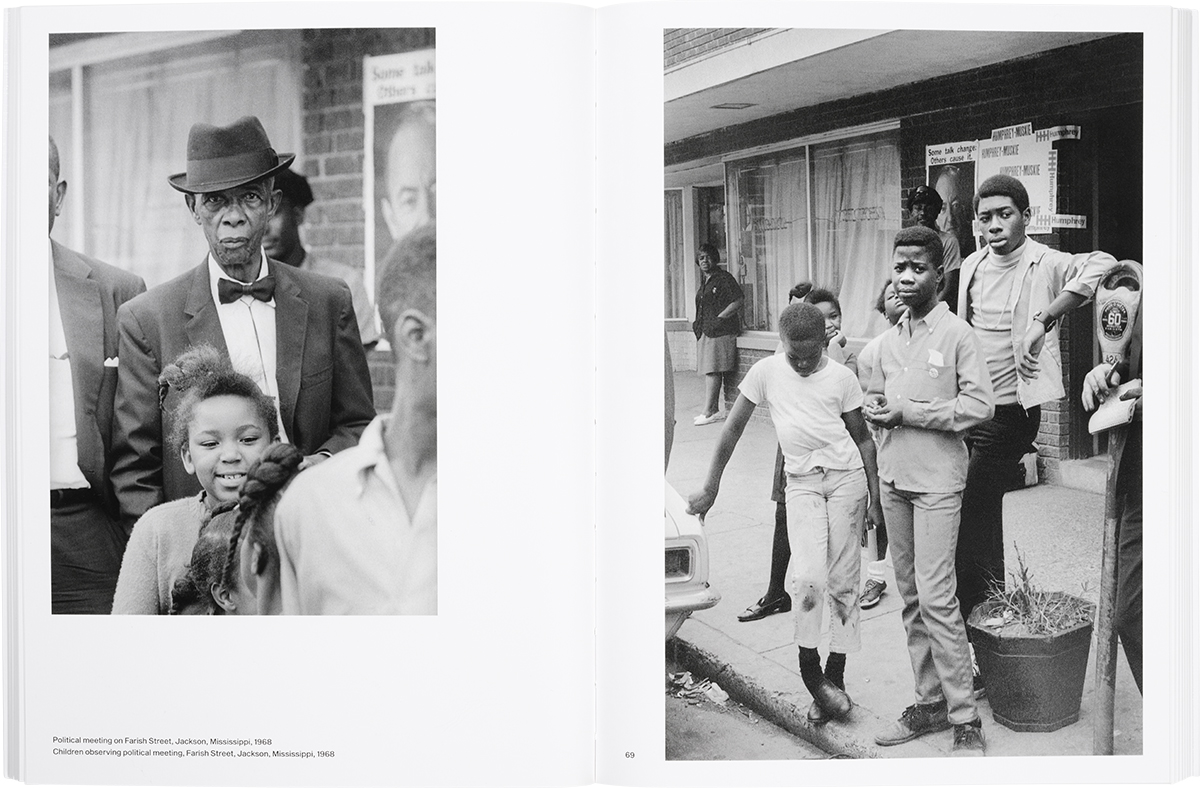

Doris Derby understood with her camera that the moments of everyday events before and after the long marches to freedom are the essential ingredients of survival. Through her lens, we witness the struggle for education, the hardship of work, the lack of rest, the benefits of community and the need for social gatherings, essential ingredients that form the bedrock of Black America’s life. Derby’s photographic moments of resistance in A Civil Rights Journey (2021) are stoic testimonies that revolution is not always a frontline masculine affair. Derby responded to the Age of Rage by producing images that travel beyond that of the engaged or committed activist, beyond the recorded events of brutal segregationist conflicts. Her labor with the lens creates praxis-based, time-shifting moments that work against the violent politics of racial time.

The Age of Rage is also a place of abstraction, where new meanings and buried feelings emerge as provocations or possible restorative solutions, where the unresolved colonial histories and inherited nightmares that dwell beyond the scrutinous eye of documentary photography come to life.

The unconscious aspect of the Age of Rage is a different form of articulation. It is a place that generates raw emotions and feelings, which can only be described as the “blues.” In the unconscious image world, feeling images must be made, reimagined, constantly reformulated and nourished so that they can wrestle with unjust histories.

The fight for equality across the human condition radically evolves out of protest. Beyond the jackboots, the batons, the water cannon, the tear gas, the bullets, the tanks, the fences, the walls, the concentration camps and all means of surveillance, history teaches that what power fears more than anything is a people on the move against injustice. Looking at the history of photography, we can understand that progress across the political terrain of human rights has been difficult. Marginalized bodies, when divided, are vulnerable to capture, control and genocide. Thinking through our past in photographs and decentering the knowledge formations of imperial lenses means that we can critically join or remake the politics of the left intersectional, aligned in mission, and truly inclusive. This will create waves of solidarity and supportive modes of resistance that strategically enable people to embrace the different ecologies of freedom and resist imperialist politics that divide and rule.