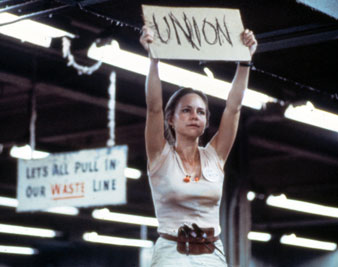

20th Century Fox/Everett CollectionSally Field in Norma Rae, 1979.

20th Century Fox/Everett CollectionSally Field in Norma Rae, 1979.

While no flying nun, Salley Field is no less than heavenly as a wife and mother, organizing her fellow workers in a Southern textile factory.

Strongly partisan movies on social themes can turn out more innocent than convincing, the characters get jerked around on the director’s strings, and God’s finger tilts the scales of virtue. Not so, however, in the case of Martin Ritt’s Norma Rae. It records a battle for union recognition in a Southern mill town (the picture was made in Alabama) and is so partisan that the resident agents of the owners wear drooping Confederate cavalry mustaches, symbols of man’s inhumanity to man. (It should be noted, though, that the real-life enemies of civic decency tend to typecast themselves; I offer as evidence the henchmen of absentee ownership in Harlan County, USA and Cohn and Schine hovering over the shoulder of Joe McCarthy in Edward R. Murrow’s famous chapter of See It Now.)

Norma Rae draws its dramatic life and a good deal of legitimate emotion, in the first place, from the intelligent, pungent, often witty dialogue of the screenplay written by Irving Ravetch and Harriet Frank Jr. Further, the principals, who know good material when it is given them, throw themselves into their parts with professional glee. Sally Field, in the title role, is a young widow with one legitimate and one bastard child, a provocative body, sharp mind and short temper. Opposite her, working single-handed (until she joins him) to rally the mill hands from their fear and lethargy, is Reuben Marshasky (Ron Leibman), a Jewish labor organizer from New York. As Norma Rae tells him, she has never seen a Jew before (his reaction to that statement is a delight), and it takes her some time to penetrate his breezy, street-tough, no horseshit manner. The growing relationship between these two is the substance of the film; they are at once a two-man commando and a couple falling deeply into a love they are too experienced to consummate. Indeed, in midpicture Norma Rae marries Sonny (Beau Bridges, who is extraordinarily effective in the recessive part of a young Southern male sapped of everything but his sweetness).

The Norma Rae-Reuben combination is dangerously “good theater”; it could easily have seemed commercially canny, touching nerves across the spectrum of the audience. It does that, to be sure, but under Ritt’s scrupulously respectful direction, Field and Leibman play their rich parts with an inner conviction and daring openness that are exciting and moving.

The picture ends when the plant’s serfs vote, in defiance of management’s threats, to be represented by the union. It ends, thus, on a crest of present victory and future hope which those who know the ways of Southern industry will find optimistic. It takes more than a successful election to convince one of those mills that a new day has arrived. However, within the frame of this story, Reuben and Norma Rae earn the joy in their triumph and each other.