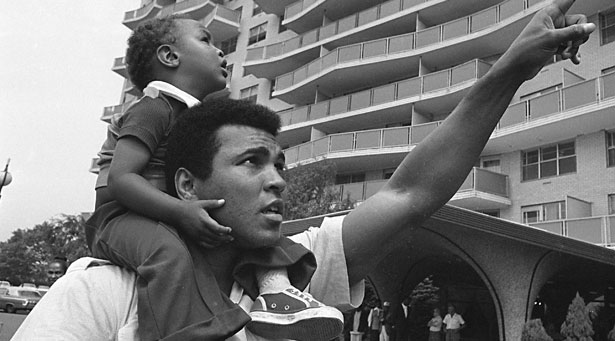

Muhammad Ali carries his son on his shoulders, Aug. 24, 1974. (AP Photo/Bill Ingraham)

I couldn’t stand the Michael Mann film Ali starring Will Smith. The problem was not the script, the cinematography or the pacing. The problem was Will Smith. This is no knock against Mr. Smith. The film’s great flaw is the fact that no one can really play Muhammad Ali except for Muhammad Ali. It feels self-evident to write, but Hollywood, even with all its magic, is incapable of recreating the charisma, physical grace, or tragic glory of the Champ.

That is why Muhammad Ali has always been served better by documentaries than dramatic films. Even when Ali played himself in the 1977 film The Greatest, it was a disaster precisely because the wicked improvisation that marked both his style of speech and boxing were thuddingly absent.

That is also why for my money some of the best sports documentaries have Ali as their central focus. When We Were Kings or Muhammad Ali: Through the Eyes of the World are classics and belong on the shortlist of the best sports docs ever made.

I write all this so it’s understood that when I say that The Trials of Muhammad Ali is the best documentary ever made about the most famous draft-resister in human history, you know that I choose those words with extreme care. What makes The Trials of Muhammad Ali, by Academy Award–nominated director Bill (The Weather Underground) Siegel so special, is that it succeeds where so many have failed. Finally we have a film that presents an honest, thorough excavation of Ali’s politics in the 1960s. Siegel, perhaps because he has experience chronicling the often messy movements of that era, is able to communicate Ali’s journey of rebellion against racism and war with nuance and without a hint of condescension.

Other films have discussed Ali’s allegiance to the Nation of Islam, but I can’t think of another film that delves as deeply into why a separatist group like the NOI would be attractive to Ali. Siegel, always off camera, interviews actual members of the NOI who were active in the 1960s to discuss what Ali’s presence meant to their organization. Other films have shown how Ali was a target of derision in the mainstream press for joining the NOI and refusing to serve in Vietnam. But I’ve never seen so much footage of people across the political spectrum—from William Buckley to David Susskind—excoriating Ali in televised settings with the Champ having to sit in a suit and seethe. Other films have discussed how Ali was sentenced to five years for evading the draft, a sentence that was eventually overturned by the United States Supreme Court, but I’ve never seen it examined to such a precise degree. This is the heart of Siegel’s film, and it’s explained in great detail why the Supreme Court—that supposedly apolitical body—desperately searched for a reason, no matter how paper thin, to overturn his sentence.

Other films have discussed Ali’s antiwar activism, but I’ve never seen such a bounty of new footage of Ali expressing his antiwar feelings in his own words. That’s truly what made The Trials of Muhammad Ali impress itself upon me like a stiff left jab. I like to consider myself someone who has studied Ali’s life. But I’d never laid eyes on most of what Siegel has unearthed. For example Ali-o-philes know that when he was banned from boxing in 1968, he starred in an extremely short-lived Broadway musical called Buck White. Actually seeing footage of his performance is alone worth the price of admission.

I do have criticisms of the film. Given the amount of time Siegel devotes to the Nation of Islam, I wish he had discussed in greater detail Ali’s separation from Malcolm X when Malcolm left the NOI, as well as the period in Ali’s life in 1969 when the NOI suspended him from membership, writing, “Mr. Muhammad Ali shall not be recognized with us under the holy name Muhammad Ali. We will call him Cassius Clay.” Their reasons for such action are confusing to this day, and I would have loved to see the implications of this in both the NOI and the broader movement explored.*

But that nitpick is like complaining about the picture frame on a genius work of art. This is a special film. It should be treasured by anyone who cares about sports, politics, the 1960s or the vivacious, loquacious, bodacious, Muhammad Ali. There are those I’m sure who will always believe that no film could possibly do Ali and his era justice. They should on principle see The Trials of Muhammad Ali, and then, humbled, find Bill Siegel and say his name.

* I was able to ask Mr. Siegel at a screening in New York why he didn’t unpack this part of Ali’s life and he answered that it was addressed but ended up, with a great deal else, on the cutting-room floor. Now I’m giddily counting the days to the DVD release so I can see all the extras.

David Remnick on the legacy of Muhammad Ali.