Earlier this month, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill became the latest front in the war on affirmative action when Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA) filed a brief in federal court attacking UNC’s use of race in its admissions process. SFFA, organized by conservative activist Edward Blum, had already filed a similar lawsuit against Harvard. Avid court watchers will recognize Blum for his zealous crusade against the University of Texas—his own alma mater—on behalf of prospective student Abigail Fisher. In that case, Fisher v. Texas, the court ruled that a diverse student body is a worthy priority, and that race can still be considered as one factor among many in admissions decisions.

The new case against UNC–Chapel Hill, though, demonstrates the tirelessness of the conservative effort to remove race from any admissions equation. Despite the Supreme Court’s decisions to keep a limited version of affirmative action alive, conservatives have succeeded in scaring many colleges into colorblindness. According to one study by researchers at the University of Toronto and Brown University, the percent of selective colleges that reported considering race in admissions dropped from 60 percent in 1994 to 35 percent in 2014.

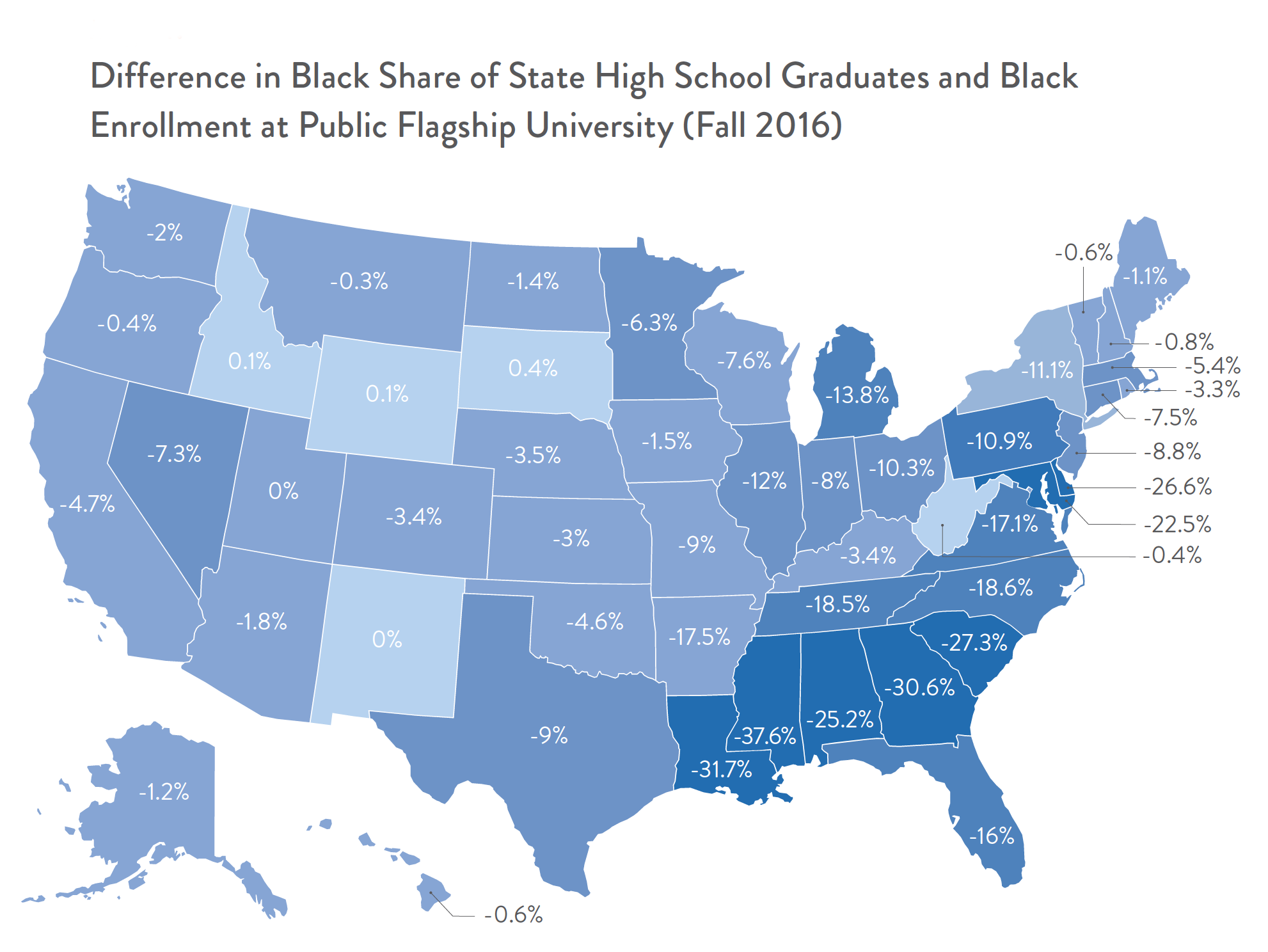

If the goal is to resegregate higher education, the efforts have largely worked. Amid budget cuts and attacks on affirmative action, elite public colleges are enrolling fewer black students than they were a generation ago. In a new report, “Social Exclusion: The State of State U for Black Students,” I take a look at the enrollment of black students across 67 selective public institutions—including each state’s flagship campus and other very selective public institutions like UCLA, Georgia Tech, Clemson, and William & Mary—across the past 20 years. I found that nearly half of these schools are enrolling a lower percentage of black students than they were in the mid-1990s. Nationally, one in six college-age people are black, but there is only one African-American among every 20 students at large, elite public schools.

To take just a few examples: In 2016, the University of Virginia’s student body was 6.5 percent black, down from 10.2 percent in 1996, and despite black students’ making up 23.6 percent of Virginia’s high-school graduating class. In Mississippi, over half of all high-school graduates are black, but blacks comprise only 13 percent of undergrads at the University of Mississippi. Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Illinois all have double-digit differences in the number of black high-school graduates in their states and the percentage of black students enrolled in state flagship campuses. For its part, UNC Chapel Hill’s black enrollment has fallen by nearly 3 percent in the past 20 years. White students make up just over half all of high-school graduates in North Carolina but 63 percent of the student body.

All of this is happening as college has become far more important as a way to grasp the lowest rungs of the middle class. It’s also happening even as black high-school graduation rates have increased across the country, dramatically in many states, creating a far more diverse pool of students.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

And certainly, this is not just a case of being gun-shy about affirmative action. As state funding has stagnated or declined on a per-student basis, colleges are under immense pressure to extract more revenue from other sources, including students themselves. The result can be greater recruitment of out-of-state or international students or wealthy in-state students who do not require need-based financial aid. This reduces the number of spots for poor or middle-class students of color.

The result is that less selective—and, critically, less well-resourced—colleges—from regional public institutions and community colleges, to historically black colleges and universities—have taken up the mantle, despite the fact that these schools routinely receive half as much support per-student from state and local appropriations. With less help from states, and virtually no help from the Trump administration, these schools are cobbling together what they can for students who have done exactly what they were told to do: graduate from high school, go to college, and better yourself.

This is all happening amid a rash of high-profile incidences of racism, social exclusion, and over-policing on elite college campuses in the past few years. In the past year alone, students of color have been targeted, or had the authorities called on them for napping in a dorm’s common room, eating lunch in a quiet spot on campus, going to their job of 14 years after working out at the campus gym, or simply going on a campus tour. The University of Virginia’s reputation was forever stained when white nationalists used Charlottesville as a hateful, and deadly, demonstration venue. It stands to reason that the empowerment of white supremacy, and the continual aggression—micro or otherwise—toward black students are more likely when those students are a smaller, and less normal, part of the typical campus experience.

It can also create a cycle that is exceedingly hard to break. With fewer peers and greater safety concerns, black students can reasonably assess that these campuses are not designed for them. After the University of Missouri was home to protests around bigotry and hate in 2015, the school saw a dip in enrollment that was particularly pronounced among black students. As one Missouri student, Whitney Matewe, explained to The New York Times, “Being ‘the other’ in every classroom and every situation is exhausting.” When campuses like UNC house Confederate statues, it also sends a clear and intimidating signal to any nonwhite student wanting to enroll.

In addition to threatening the social fabric of our campuses, it makes it harder to put public resources into the schools that desperately need them. Each state’s public flagship campus carries tremendous political and economic clout; they often produce titans of business, elected officials. Many of these schools have also seen deep cuts, but in some cases can rely partially on the largesse of wealthy alumni, which only further threatens to exacerbate a deep racial wealth gap that persists—and even grows—at every education level. The median college-educated white household has over $200,000 in wealth, compared to under $50,000 for the median black college-educated household. The wealth gap has too many historical causes to name, but eliminating the ability of black students to enroll in the same selective schools will not help.

This is why the effort to dismantle affirmative action is so dangerous. It is one of the few tools that we have to expand opportunity in an era of resource scarcity, when predatory colleges are being given new life by the Trump administration and higher education is a fraught endeavor for many students of color. We should be doing all we can to beat back right-wing efforts to make college campuses less diverse. Because up to this point, we’ve been doing a good enough job of it on our own.