THE NATION CLASSROOM

American History as It Happened

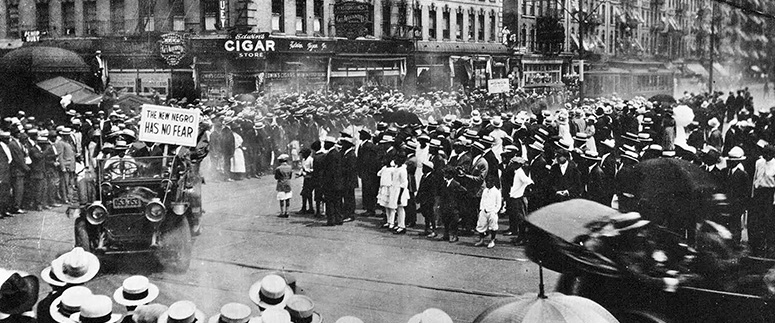

RACE RELATIONS and CIVIL RIGHTS

MODULE FOUR: 1919-1929

DBQ: In the 1920s, Americans had widely differing opinions about the proper status of African Americans in US society. Discuss those contrasting ideas, and demonstrate ways in which they were expressed during the decade.

|

DOCUMENT ONE Source: “Wanted, A More Excellent Way,” letter to the editor by Claude McKay, The Nation, August 16, 1919 Sir…I am deeply interested in knowing what reasonable course [The Nation] would advocate for the American Negro to adopt in helping to destroy the national pastime of lynching… I have lived in the South, in the West, and in the East, not without remarking that Negroes are surrounded everywhere by mad dogs in human form. When a mad dog breaks loose, we call a policeman, and if one is not in sight, we kill the dog if we can. To me a lynching-mob bears a great resemblance to a pack of mad mongrels; but I may be wrong. Being black, I may see the hideous thing only through the eyes of prejudice, and not so clearly as you do from your pedestal of pure pity. But what would you advise Negroes to do when the Federal or State Government withholds from them its protection, as it invariably does? Should they stand by with folded arms and see a member of their race tortured and burned? Should a Negro let himself be taken and tormented without show of resistance? Should Negroes remain supinely inactive while the womanhood of their race is outraged (and, incidentally, that of their tormentors cheapened)? In short, should not a Negro defend himself when attacked by the chivalrous Caucasian? |

|

DOCUMENT TWO Source: “A Question to Democracy” by Faith Adams, The Nation, November 10, 1920 The Gold Star has disappeared from my neighbor’s window, for two years have elapsed since the Armistice. The boy who went out from the house next door was the eldest of the family. I know that he died for Democracy. Yet I never saw the gold emblem that marked his sacrifice without being conscious of a vague uneasiness because I know that my neighbor’s son died for something he had never known and would not have known had he lived. When the L___s first moved into our street in B____, they caused no small commotion. They were the only middleclass colored people in our small suburban community. [To our neighbors]…the idea of a colored physician and his family moving into one of the best houses on Elm Street was preposterous…. They want the same advantages for their children that we want for ours. They moved to Elm Street to obtain those advantages…. So far as possible in our Christian Democratic community, we have made it impossible for them to achieve this. Of course we have not been entirely successful. We are a Northern community and there are still traces of respect for the individual’s civil rights written into our laws and upheld by our courts. We have so succeeded, however, that I, who gave no sons to my country, cannot remember the Gold Star that used to hang in my neighbor’s window without a feeling of humiliation. |

|

DOCUMENT THREE Source: “The Eruption of Tulsa” by Walter F. White, The Nation, June 29, 1921 What are the causes of the race riot that occurred in such a place [as Tulsa, Oklahoma]? First, the Negro in Oklahoma has shared in the sudden prosperity that has come to many of his white brothers, and there are some colored men there who are wealthy. This fact has caused a bitter resentment on the part of the lower order of whites, who feel that these colored men, members of an “inferior race,” are exceedingly presumptuous in achieving greater economic prosperity than they who are members of a divinely ordered superior race.… This was particularly true of Tulsa, where there were two colored men worth $150,000 each; two worth $100,000; three $50,000; and four who were assessed at $25,000. In one case where a colored man owned and operated a printing plant with $25,000 worth of printing machinery in it, the leader of the mob that set fire to and destroyed the plant was a linotype operator employed for years by the colored owner at $48 per week. The white man was killed while attacking the plant. Oklahoma is largely populated by pioneers from other States. Some of the white pioneers are former residents of Mississippi, Georgia, Tennessee, Texas, and other States more typically southern than Oklahoma. These have brought with them their anti-Negro prejudices. Lethargic and unprogressive by nature, it sorely irks them to see Negroes making greater progress than they themselves are achieving. |

|

DOCUMENT FOUR Source: “The Ku Klux Klan: Soul of Chivalry” by Albert De Silver, The Nation, September 14, 1921 Just before Election Day [1920], five hundred members of the Ku Klux Klan marched in costume through the streets of Jacksonville, Florida, following the fiery cross, “supposedly,” according to The New York Times, “as a warning to Negroes to attempt no lawlessness at the polls on Tuesday.” It is of record that few colored people voted in Jacksonville on Tuesday. “White supremacy” was maintained. |

|

DOCUMENTS FIVE and FIVE A Source 5: “Jim Crow in Texas” by William Pickens, The Nation, August 15, 1923 The classics tell about the tortures invented by the Sicilian tyrants, but the Sicilian genius for cruelty was far inferior to that of the fellow who contrived the Jim Crow [train] car system…. Fourteen states have Jim Crow car laws…. I sit in a Jim Crow [car] as I write, between El Paso and San Antonio, Texas. The Jim Crow car is not an institution merely to “separate the races”; it is a contrivance to humiliate and harass the colored people and to torture them with a finesse unequaled by the cruelest genius of the heathen world. The cruder genius broke the bodies of individuals occasionally, but Jim Crow tortures the bodies and souls of tens of thousands hourly…. One must be an idiot not to comprehend the meaning and the aim of these arrangements.…There is no more reason for a Jim Crow car in public travel than there would be for a Jim Crow path in the public streets. Source 5a: Letter to the editor (response to “Jim Crow in Texas” article in August 15 issue), The Nation, September 19, 1923 SIR: The policy of the Missouri Pacific Railroad in the handling of colored traffic is necessarily in adherence to the regulations prescribed by the State and Federal governments, over the creation of which the railroad had no control whatever. The segregation of races has been built upon a traditionally peculiar racial situation [that] naturally exists in many of the Southern States, and, in my opinion, it is vitally essential to the peace and welfare of the territory involved. A reading of Mr. Pickens’s article impresses me with a tendency to exaggeration. |

|

DOCUMENT SIX Source: “Negroes in College” by W.E.B. Du Bois, The Nation, March 3, 1926 The American Negro is striving for higher education as never before. In the school year 1924–1925, 752 Negroes received their first degree in arts, 44 were made masters in arts, 4 received their doctorates in philosophy and science, and 6 were elected to the Phi Beta Kappa; while 395 received professional degrees. But this represents a minimum, accomplished through great difficulty and discouragement and is not half or perhaps a third of what the American Negro could and would do today if properly encouraged. |

|

DOCUMENT SEVEN Source: “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain” by Langston Hughes, The Nation, June 23, 1926 Jazz to me is one of the inherent expressions of Negro life in America; the eternal tom-tom beating in the Negro soul—the tom-tom of revolt against weariness in a white world, a world of subway trains, and work, work, work; the tom-tom of joy and laughter, and pain swallowed in a smile…. Let the blare of Negro jazz bands and the bellowing voice of Bessie Smith singing the Blues penetrate the closed ears of the colored near-intellectuals until they listen and perhaps understand. Let Paul Robeson singing “Water Boy,” and Rudolph Fisher writing about the streets of Harlem, and Jean Toomer holding the heart of Georgia in his hands, and Aaron Douglas drawing strange black fantasies cause the smug Negro middle class to turn from their white, respectable, ordinary books and papers to catch a glimmer of their own beauty. We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame. If white people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, it doesn’t matter. We know we are beautiful. And ugly too. The tom-tom cries and the tom-tom laughs. If colored people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, their displeasure doesn’t matter either. We build our temples for tomorrow, strong as we know how, and we stand on top of the mountain, free within ourselves. |