How We Defeated Trump on Jimmy Kimmel—Plus, the Attacks on Harvard, Past and Present

On Start Making Sense: Bhaskar Sunkara analyzes the resistance to Trump’s attacks on freedom of speech, and Beverly Gage talks about Anti-intellectualism in American Life.

Here's where to find podcasts from The Nation. Political talk without the boring parts, featuring the writers, activists and artists who shape the news, from a progressive perspective.

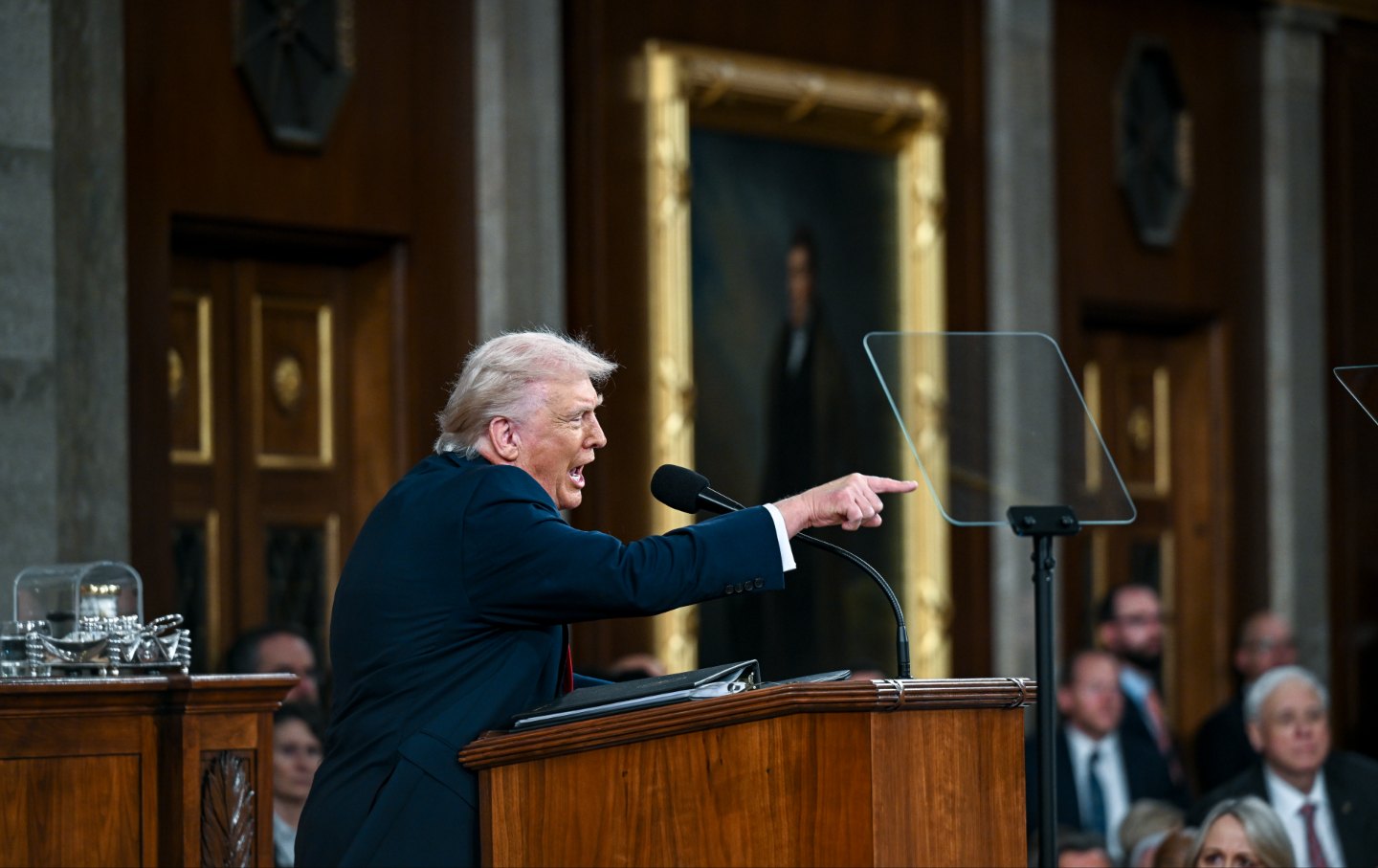

Trump is trying to block speech that criticizes him. Last week began with JD Vance complaining about an article in The Nation that criticized the ideas of Charlie Kirk. Two days after that, ABC suspended Jimmy Kimmel. And a few days after that, a protest movement forced ABC to put him back on the air. Bhaskar Sunkara comments on the fight over freedom of speech – he's president of The Nation Magazine.

Also: Attacking Harvard is not unique to Trump — for decades, indeed for centuries, American politicians have made hay by going after Harvard. Historian Beverely Gage talks about what’s familiar, and what’s new, in Trump’s efforts – based on a reconsideration of Richard Hofstadter’s classic 1963 book “Anti-Intellectualism in American Life.”

Advertising Inquiries: https://redcircle.com/brands

Privacy & Opt-Out: https://redcircle.com/privacy

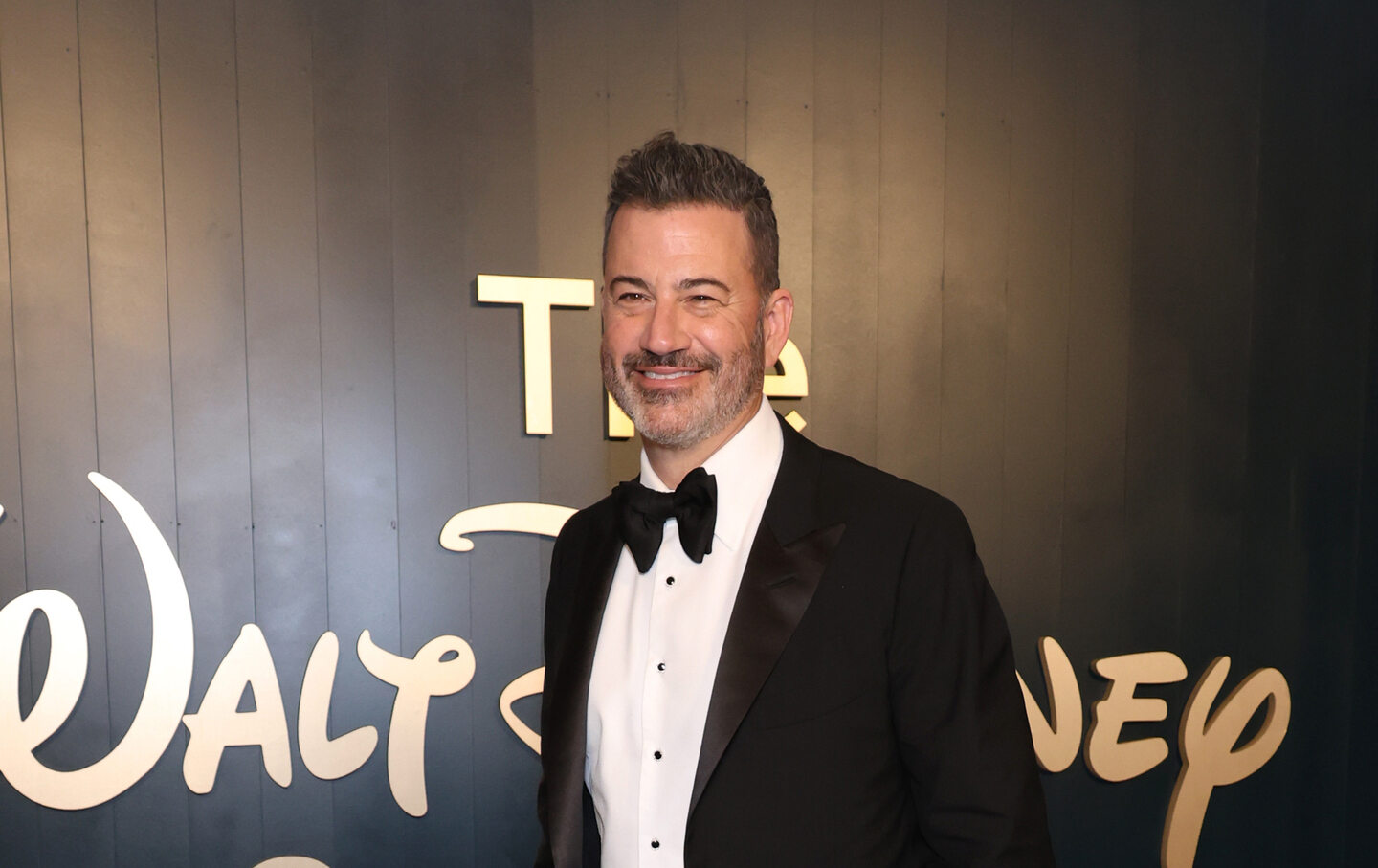

Jimmy Kimmel at The Walt Disney Company’s 77th Emmy Awards Party on September 14, 2025, in Los Angeles.

(Chad Salvador / Variety via Getty Images)Trump is trying to stop speech that criticizes him and his administration. Last week began with JD Vance complaining about an article in The Nation that criticized the ideas of Charlie Kirk. Two days after that, ABC suspended Jimmy Kimmel. And a few days after that, a protest movement forced ABC to put him back on the air. Bhaskar Sunkara comments on the fight over freedom of speech—he’s president of The Nation magazine.

Also: Attacking Harvard is not unique to Trump. For decades, indeed for centuries, American politicians have made hay by going after Harvard. Historian Beverely Gage talks about what’s familiar, and what’s new, in Trump’s efforts—based on a reconsideration of Richard Hofstadter’s classic 1963 book, Anti-Intellectualism in American Life.

Subscribe to The Nation to support all of our podcasts: thenation.com/subscribe.

Here's where to find podcasts from The Nation. Political talk without the boring parts, featuring the writers, activists and artists who shape the news, from a progressive perspective.

After Senate Democrats block the SAVE act, Trump is likely to declare a national security emergency – claiming China could interfere in the midterms – as a basis for restricting voting. David Cole comments; he’s former legal director of the ACLU.

Also: Congress must challenge Trump’s war on Iran and assert its constitutional duty to take up War Powers resolutions and assert its primacy over matters of war and peace. John Nichols explains.

Advertising Inquiries: https://redcircle.com/brands

Privacy & Opt-Out: https://redcircle.com/privacy

Jon Wiener: From The Nation Magazine, this is Start Making Sense. I’m Jon Wiener. Later in the show:

Attacking Harvard is not unique to Trump – for decades, indeed for centuries, American politicians have

made hay by going after Harvard. Historian Beverely Gage will talk about what’s familiar, and what’s

new, in Trump’s efforts – based on a reconsideration of Richard Hofstadter’s classic 1963 book “Anti-

Intellectualism in American Life.” But first: How we defeated Trump in his effort to silence Jimmy

Kimmel. Bhaskar Sunkara has our analysis–in a minute.

[BREAK]

Last week, after Trump’s approval ratings hit new lows, he made it clear he’s trying to stop speech that

criticizes him and his administration. That was the week that began with JD Vance complaining about an

article in The Nation that criticized the ideas of Charlie Kirk. And two days after that, ABC suspended

Jimmy Kimmel. And on Monday a protest movement forced ABC to put him back on the air.

For comment, we turn to Baskar Sunkara. He’s president of The Nation magazine. He’s also founding

editor of Jacobin, author of the book, ‘The Socialist Manifesto,’ and a regular contributor to the

Guardian who also writes for the New York Times, the Washington Post, lots of other places. Bhaskar,

welcome back.

Bhaskar Sunkara: Thanks for having me.

JW: The big news this week is that the boycott of Disney demanding that they bring back Jimmy Kimmel

succeeded. ABC started airing Jimmy Kimmel again on Tuesday this week in response to a wave of

protest: at least five Hollywood unions, collectively representing more than 400,000 workers, publicly

condemned the company. The Screenwriters Guild organized a picket line outside the main gate at

Disney headquarters in Burbank. 500 celebrities signed the ACLU’s open letter in defense of free speech.

It included big names like Meryl Streep and Tom Hanks. And a consumer boycott began of Disney

streaming. The boycott against Disney–the parent company of ABC — as measured by internet searches

for ‘Cancel Disney plus,’ was four times as large as any similar boycott over the past five years. And

Disney’s market value dropped by almost $4 billion.

If you had said to me a week ago, let’s organize a consumer boycott in defense of free speech, I would

not have been very optimistic about it. How do you think this outpouring of protest defeated Trump?

BS: To begin with, there’s a reason why we all believe in liberal values like free speech, but why many of

us go beyond that sort of negative freedom — because obviously in our society you need some sort of

money or claim to resources in order to truly exercise your freedom of speech. In the case of ABC, they

got pressured by some right wing affiliate owners of theirs, and they were afraid about the lost income

from advertisements If they weren’t running Kimmel’s show. They were also pressured by the

government, which is obviously more disturbing, or more uncommon, I should say, in American

democracy. And now of course, they’re facing pressure from the other side. They’re facing pressure

from labor unions. They are facing pressures from consumers. I guess they’ve weighed that. They’re

more afraid of the latter than the former.

So I would say that in general, I think consumer boycotts are only useful if they’re connected with some

sort of title labor or some sort of organized progressive group. So of course this is not the United Farm

Workers Campaign, but at the very least it does show a willingness in civil society to resist what Trump is

doing. And I don’t think we should be cynical about that. We shouldn’t take it for granted. If you look at

other countries, you look at Turkey, you look at a Brazil under Bolsonaro, you look at India under Modi,

we shouldn’t take for granted that this civil resistance will exist. We’re seeing it now in the United

States, but at the very least, it’s demonstrating to Trump and his supporters that there are limits to what

they can do. And I think we’re in a situation where I both don’t want to overstate how far along the road

to fascism or authoritarianism the US is, but it is deeply disturbing that Donald Trump wants to take us

along that road. And I think that in itself should be very worrying to us. But I am happy to see any sort of

civil resistance to his agenda.

JW: And then let’s talk about the article in The Nation that JD Vance was attacking. It was by Elizabeth

Spiers, it was headlined ‘Charlie Kirk’s legacy deserves no mourning,’ and she concludes ‘I won’t

celebrate his death, but I’m not obligated to celebrate his life either.’ Vance said ‘it made it through the

editors, and of course, liberal billionaires rewarded that attack.’ And he cited in particular George

Soros’s Open Society Foundations and the Ford Foundation as funders of The Nation. And then other

Trump people suggested they would go after all the liberal foundations, trying to deny their tax exempt

status as nonprofits.

But you’re the president of The Nation. Let me get this straight. You sent that article about Charlie Kirk

to George Soros for his approval, and then he sent a check.

BS: Well, Jon, I think you and I know this better than most, but it’s worth saying that The Nation would

love to receive money from George Soros or any other donor that respected our editorial independence.

We’re not in fact funded by the Open Society foundations. We were funded once, I believe a one time

donation in 2019 in the amount of a hundred thousand dollars–it’s all public record–by the Ford

Foundation, to support our intern program. And of course we’re deeply grateful for that. But that

amounted to about 1% of our budget of that year. So The Nation’s a publication that has run losses and

all but I believe three of its 160 years. So the a hundred thousand really does make a difference. It does

change what we’re able to do.

But I think what JD Vance was trying to do was one, of course the antisemitic dog whistle against George

Soros. Through some magic trick, the right has turned a Hungarian banker who is a lifelong anti-

communist into a Marxist puppet master. And the slight of hand, the magic trick of is of course just the

classic trope of antisemitism and ‘Judeo-Bolshevism.’ And Vance is too smart to really believe that, but

he’s going along with it to cater to his base.

But they’re saying that also in part because they want to make it seem like there’s no organic audience

for left-wing opinion in the United States. When we look at the media ecosystem in the us, I think

neither of us are afraid to say that yes, there is a real audience for places like Breitbart and the Daily

Caller. There are a lot of people who are politicized by issues of immigration, by all sorts of cultural and

economic issues, and are on the Trump side. That’s a political problem. We have to confront how to win

over those that can be won over and how to politically isolate the other so they can’t cause damage to

the American Republic or broader egalitarian agenda.

But I think on the right, there is a tendency to depict everything that happens left to center as being

astroturf, by big foundations and big money, when an honest accounting would say that the institutions

like The Nation are not particularly well funded, especially in comparison to our peers on the right, like

Turning Point USA and also our more centrist parts in the media ecosystem. So I think that’s the first

thing that warrants correction.

But as for the article itself, I think it’s worth addressing the difficulty of writing something about

someone who so recently died. And I think there’s a reason why we publish on someone like Charlie

Kirk: It’s because he’s a public figure. And immediately when that assassination happened, like a lot of

Americans, my first thought turned to just the fact that this is a horrible thing for a republic, for

someone engaging in politics and debate to be gunned down, especially in front of an audience of

students and people, who we want to engage in politics and exchanging ideas.

It was horrific at so many different levels and I think bad for our society. And then of course, the human

tragedy: this is someone’s husband, this is someone’s father, this is someone’s son.

But because he’s a public figure, the right is going to immediately and did immediately turn him into not

only a martyr but a saint. And at that point, because he’s a public figure, we need to examine, while all

the attention’s on him and while the right is creating a narrative of what he was about, our analysis of

he stood for and what he devoted his political life to. This isn’t attacks on his personal life or anything.

This is a debate about the life and legacy of a public figure who tried to do mass politics. And I think it’s

very much fair game, though, of course, like any topic like this, it should be approached sensitively with

an eye towards winning over not just the 20% of left-wing partisans in the country or 20% of right wing

partisans, but the 60% of Americans in the middle who were looking at this tragedy and probably didn’t

hear about or know about Charlie Kirk before he died, but are sensitive to the hyper-polarized tone of a

lot of commentary and discussion around politics in the country.

JW: One of the more significant aspects of all of this was that Trump administration suggesting that they

were going to go after the liberal foundations and try to deny them of their tax exempt status because

they support groups that are critical of Trump, supposedly.

BS: The disturbing thing is that he wants to use the tools of the state to clamp down on dissent. And I

think the institutions of American republicanism are holding up this time around to some degree. I think

it held up better in its first term. It’s holding up a little bit worse in its second term. But what’s going to

happen in 20 years or 30 years, this is the trajectory that the country is on. I think it’s quite a disturbing

one as far as how they’ve traditionally gone after organizations of the left before and publications in

particular. Almost every publication in the US that’s in print is dependent on the periodical status from

the US Postal Service. So that’s another tool that has been wielded in at times. Like during the first Red

Scare, they actually prohibited the post office from sending out certain publications. So there’s a lot of

avenues they can use.

The Nation, thankfully, is not organized as a nonprofit organization. We are dependent on periodical

status and our mailing privileges. Of course, Reagan did, I believe in his administration, try to go after

Mother Jones’s nonprofit status, and Mother Jones beat back that attempt. So I do think that we need

to be prepared to defend the first organization. It probably won’t be The Nation, but the first

organization that is targeted unfairly by the Trump administration.

Also, we have to be consistent across all lines. The Obama administration, a lot of these Tea Party

nonprofits were engaged in very explicit politicized activity. So the Obama IRS did go after them as far as

I could tell. I haven’t studied it deeply. There was some merit to some of these cases. Obviously we don’t

want believe in a kind of a tit-for-tat attack on either side in civil society.

But my big worry, Jon, is when I think about my own politics or the people that I know that have come

out of the far left, we are essentially liberals to some degree, we have reconciled socialism and

liberalism. In my case, I come from a socialist political background, as you know. So in other words, if

you give us absolute power, there will still be tomorrow free speech. A bill of rights will be protected,

and you would still have multi-party democracy. You might not like what we’ll do to property rights or

this, that, or the other policy, but that would happen.

But if you gave someone absolute power like Donald Trump or a lot of these figures in the right,

especially figures like Steven Miller who is just flat out far more scarier than Donald Trump, just in terms

of his rhetoric and the sorts of things he invokes, I honestly we believe we would live under fascism. I

really don’t believe they have any respect for liberal norms or rights, and that’s deeply disturbing. The

polarization in the country is not even; one side is radicalized a lot more than the other.

JW: One key step that’s particularly ominous that Trump has just taken came on Monday when he

declared Antifa a domestic terrorist group. Now the United States does not have a domestic terrorism

law. There is no such thing as a list of domestic terrorist groups which are banned, and Trump doesn’t

have any authority to designate what he calls Antifa as a foreign terrorist organization without approval

of Congress. But let’s go back a step. Is there an organization in America that calls itself ‘Antifa’? I

thought it was more an ideological term.

BS: There is no organization that calls itself an Antifa. It is an ideological, antifascist term. It’s about

opposition to right-wing politics, opposition to fascism. A lot of these people who have used that

identification in the past are anarchists. Some are communist or socialist. There’s been, you would say

mass movements, particularly in postwar Germany and other places that have used a lot of the banner. I

think there’s a willingness to engage in direct action by a lot of these people with this ideology to disrupt

fascist marches and organization just basically, I think part of their theory is we can’t afford to kind of let

fascism grow and be acceptable as political opinion. We have to kind of try to stomp it out in its

grassroots, and we could agree or disagree with that approach.

I think generally, I think that the banner and defense of free speech–free speech, of course, short of

direct incitement–is not only a good in and of itself, but I also think it puts the left in the long run on a

better political terrain.

But with Antifa there certainly is no organization or no hierarchy. There’s no movement structure here. I

mean, these are very loose knit networks. These are networks that are ideologically anarchist. It’s like by

nature they’re not trying to elect some sort of central committee and take marching orders in some sort

of Len way. So both in theory and practice, it doesn’t make any sense. And also it doesn’t take money to

organize a protest and can go after a fascist group. It doesn’t make sense at any level. I think from what I

can tell, the vast majority of anti-fascist activity in the US is legally protected activity to the extent anti-

fascists engage in direct action that crosses certain lines. I mean, that’s individual questions and

individual police issue. But this is very scary even with organizations that have had real form. I don’t

know anyone on the left that believes in a ban for even the KKK an outright band. So I think that

historically we’ve been, at least since the 1950s, the left has uniformly been on the right side of a lot of

these free speech issues. And we should continue to be.

JW: A lot of people say that what’s happened in the last week is a significant escalation of Trump’s

efforts to move in a fascist direction. And I think it’s important to ask, why is this happening now? I think

it’s because Trump’s popularity continues to decline. He’s incredibly unpopular.

His favorability ratings have dropped 23 points since he took office, according to this week’s polls.

He’s the most unpopular president in American history.

Americans oppose pretty much everything he does.

Lemme just give you a couple of highlights from the approval polls. ‘Do you favor or oppose Trump

sending troops to American cities?’ favor, 42%; oppose, 58%.

‘Do you favor or oppose Trump’s tariffs?’ favor, 38%; Oppose 62%.

‘Do you approve or disapprove of the way Trump is handling free speech?’ approve, 35%; disapprove

55%.

And this extends even to the people who were part of his coalition. Young people, Latinos,

independents, all disapprove of him by dramatic margins. Right now, even among Republicans, among

Republicans 45 or younger, 61% this week said’ the country is headed in the wrong direction’. And

Trump knows this.

BS: Yeah, I mean, I think it’s very clear that he has a minoritarian agenda. It’s very clear that there’s a lot

of opposition to what he’s doing. It’s very clear that, even when there’s violence in the country that

people can’t attribute to the right wing, or to the Trumpist right, a lot of people associate it with the

breakdown and the extreme polarization that Trump has fostered.

If you look now at what he’s doing, the very erratic public health messaging around vaccines and so on,

it’s really undermining a lot of institutions in the US. And this is all before the true impact of his

economic policies are felt by ordinary Americans. So the tariff policy, a lot of the impact hasn’t been felt

yet. A lot of the impact of what he’s doing to the deficit and the cuts to the social safety net. At the same

time, we’re giving massive giveaways to the ultra rich. This won’t be implemented and really seen for a

couple of years to come.

So I think Trump will be long gone by the time we are dealing with a lot of these consequences. And the

consequence might manifest itself in the fact that we might have a Democratic administration and

Congress sometime in the early 2030s, but it’s unable to get anything done. They can’t do the kind of

deficit spending that Biden did. They can’t do the kind of big ambitious plans that at least Obama said he

was going to do early on in his term. So I think there’s a lot bad here.

Where I worry about just following the numbers is that the general trend of American politics is towards

a kind of rejection of politicians of all types across the spectrum. Democrats are very unpopular.

Congress is very unpopular. Democratic politicians are not there ready to step in and fill the void.

So we might just be at a point where even though Trump is at historic levels of disapproval, we have to

also factor in the net of how far below the median Democrat is he, or the median member of Congress

is.

I think we’re kind of getting to the point where there’s a lot of distrust in governments, in the state as a

whole, in the long run. Obviously this terrain benefits the right, and it will only encourage a certain

tendency of American politics to say, we need a stronger executive — because if Congress at gridlocked

and could get nothing done, if people don’t trust the civil service and the civil service is all gutted, then

maybe people will one day want not a kind of good, smart, social democratic government, but instead

they might want a better or different version of Trump — who’s willing to cut through the bureaucracy

and deliver things for the people. And I think unfortunately, that’s a trend that American democracy is

headed towards.

JW: We have one bright light on our horizon: Zohran Mamdani.

BS: Yeah. I think Zohran is a generational politician in his ability to communicate with people. I

sometimes get the pleasure of, when we have members of Congress visiting from DC, they come to New

York and whenever they want to do a meet-and-greet with members of the kind of social movement left

and others, a few of them at least trust me to arrange these meetings.

So I arranged a meeting, I won’t say with whom, but with a couple, two members of Congress, Zohran,

and some social movement activists. And after that meeting, this must have been December 23 or

January, 2024, I told Zohran he was the best national politician at the table. He was the most impressive

one, just his charisma and speaking, whatever. And I suggested that maybe he should run for Congress

soon. Obviously he had bigger and better things planned for himself. But I think he’s a truly dynamic

figure.

There’s a lot of enthusiasm around politics in New York, and I should say this is what a politicized society

looks like that is a good one. People are wearing Zohran shirts, but the messages are all friendly and

inclusive. If you look at even his favorability rating, in one poll among Republican voters, he was plus one

in favorability. So not that favorable, but all things considered, plus one. If you talk to ordinary Zohran

voters about who their number two is, at some sort of glib personal level, they’re like, well, Curtis Slewa,

the Republican candidate, seems like an honest guy. It kind of is a throwback to what politics could be,

which is better, or about a positive program that isn’t about trying to hunt for enemies. And I think it

just makes it an easier thing to do.

It’s a fun thing to go to a Zohran event. He had thousands of people doing a scavenger hunt that his

team put together in the last minute. It is basically, I hate to use this word, I feel like the Harris campaign

almost ruined it, but it’s a joyful campaign — and it’s one that I think we should really be proud of, and I

think we’re going to be studying for many years to come on the left. It really is a landmark that

seemingly came out of nowhere.

JW: Baskar Sunkara — he’s president of The Nation. Bhaskar, thank you for talking with us today.

BS: Thanks for having me, Jon.

[BREAK]

JW: Trump intensified his attacks on Harvard last week, placing the school under something called

heightened cash monitoring and threatening further enforcement action if the school does not turn over

records to prove it’s no longer considering race in admissions. And of course, this comes after Trump cut

2.6 billion in research funding to Harvard and after Harvard has been winning a court case to get those

funds back. But attacking Harvard is hardly unique to Trump for decades. Indeed, for centuries,

American politicians have made hay by going after Harvard and indeed going after professors and

intellectuals in general. For comment, we turn to Beverly Gage. She teaches history at Yale and her book

on j Edgar Hoover, titled ‘G-Man,’ received the Pulitzer Prize in biography, the Bancroft Prize in

American History, and the National Book Critics Circle Award in biography. We talked about it here. In

fact, it was one of our best segments of the year, so it’s a pleasure to say: Beverly Gage, welcome back.

BG: Thanks, Jon. It’s great to be here.

JW: You wrote recently about anti-intellectualism in American life, but that’s not an original idea of

yours.

BG: That’s correct. I was writing about a very famous book by the historian, Richard Hofstadter, ‘Anti-

Intellectualism in American Life.’ The book came out in 1963 in a very different political moment, a very

different moment for higher education. But I thought it would be an interesting time to return to that

book and see what it had to say that might be useful today.

JW: We don’t want to say there’s nothing new about Trump’s attack on Harvard and all of higher

education, but before we talk about what’s new, let’s talk about the pattern that we find in history. How

far back did Hofstadter go in finding anti-intellectualism and criticism of Harvard in American history?

BG: He went back before there was a United States of America. Criticism of Harvard, of higher

education, suspicion of educational elites, he really traced back to very early in the country’s history,

before it was even a country. And I think there were a couple of things that were quite interesting to me

about the book. On the one hand he’s tracing a lot of these continuities, and in fact, when this book

usually comes up in conversation, it says, shorthand for Americans–they’re all a bunch of rubes and

always have been. They’ve never liked their professors. But actually Hofstadter’s book is much more

interesting than that. And that was the piece of it that I really wanted to lean into and think about and

write about in our moment.

JW: Let’s note that eight presidents of the United States have graduated from Harvard, or at least

different parts of Harvard. They include Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, John F.

Kennedy, George W. Bush in Barack Obama. George W. Bush actually went to Yale undergrad, but went

to Harvard Business School, so he

BG: was a history major.

JW: There you go. And Obama of course went to Columbia but then went to Harvard Law, so he counts

too. You have a favorite sentence in Hofstadter’s book, Anti-Intellectualism in American Life. Please read

it to us.

BG: This was one of the sentences that really struck me as an essential theme of the book. As I said, it’s

often talked about as Hofstadter’s, great critique of ordinary Americans, but a very large part of the

book is a critique of his fellow academics and intellectuals. And this sentence really stood out to me in

that context. He said, it is rare for an American intellectual to confront candidly the unresolvable conflict

between the elite character of his own class and his democratic aspirations.

JW: And it’s hard for you and me to deny that this is true in our own day as well as in 1963.

BG: I think that he articulated very well one of the challenges of being an academic and intellectual in a

broad democratic society, which is that certain forms of educational training are, by their very nature,

the creation of a certain kind of elite, a certain kind of expertise, a certain kind of authority, at least in

theory. And of course, one of the things that we were seeing in Hofstadter’s moment that we’re seeing

today, again, is a debate about whether that expertise and that authority and that elite nature is

deserved, is worthwhile, is something that anybody actually wants. And I think we’re having a deep

contest over that in the way that they were, especially in the 1950s, which is what Hofstadter was

responding to.

JW: Historians love historical context. Let’s talk about the historical context in which Hofstadter wrote

‘Anti-intellectualism in American life.’ You said it was published in 1963, but his concern really was the

fifties, and of course Joe McCarthy, who had actually fallen from power almost 10 years before the book

was published.

BG: Yeah, he was writing the book at a moment when many of the battles he was describing had in

some sense been resolved, at least temporarily, for a few years, or for a particular generation. But what

really concerned him was the rise of McCarthyism, the kinds of pressures that put on universities, and

particularly on questions of speech in the 1950s, particularly for those on the left, but also the ways in

which that was a kind of bottom up phenomenon and had produced all sorts of critiques of intellectuals,

educated people, not only as Marxists and Stalinists, but as worthless, as undemocratic: A whole range

of critiques that we see that resonate throughout a lot of other periods of American history too.

JW: There was one presidential election during the heyday of Joe McCarthy–that was 1952, where we

had a conflict between one candidate who was at least regarded as an intellectual and one who was not.

Adlai Stevenson, the governor of Illinois, versus Ike, who had been president of Columbia but was

thought of as a military man more than as a scholar. Hofstadter thought it was a major confrontation.

BG: Right. It’s a little funny to look back on the Eisenhower-Stevenson campaigns of which there were

two as these high dramas. To us, there may be a little bit of a punchline, maybe among the least

interesting presidential campaigns of the 20th century, but the stakes seemed very high at the time. And

in fact, the repudiation of Adlai Stevenson was considered to be a repudiation of ‘the thinking man,’ as

Hofstadter would have put it. And as many mid-century liberals understood it.

Now, of course, Eisenhower turned out to be pretty great for higher education, and so I really think

Eisenhower is getting a bad rap here. He certainly helps to produce some of the federal funding system

that came to be so important. But for Hofstadter in that moment, this was a ferocious contest, and he

really felt that the intelligentsia had lost.

JW: I was trying to remember, was Stevenson actually an intellectual?

BG: Well, he I think liked to present himself as a man of ideas, and I think he was quite beloved by

liberal intellectuals in particular in his moment.

JW: I think he spoke in long sentences and paragraphs.

BG: Right? He might be the worst kind of intellectual. He didn’t win elections and he was pretty

incomprehensible.

JW: And even in the 1950s, Hofstadter could see that the attacks on the campus Marxists were really

about something else. Please explain.

BG: During the 1950s, of course at the height of the Red Scare, the accusation that universities were

harboring communists in a literal sense, that there were members of the Communist Party on the

faculty, primarily, and to some degree in the student population, but also that universities were hotbeds

of Communistic ideas much more broadly conceived. This was really the central charge of its moment

during the Red Scare and the Cold War. And Hofstadter’s case is that, look, there were some communist

professors, right? There are ways in which he openly acknowledged that universities tend to lean more

left than a lot of other sectors of society, but he also saw the attacks as very politically motivated in that

case, partly a matter of partisan politics being deployed by the Republican party by figures like Joe

McCarthy. And then also part of a much broader attack on kind of liberal authority, on the New Deal,

and particularly on this whole generation that had really come into power with the New Deal. All these

professors and economists and sociologists and thinkers and commentators who had entered the New

Deal state and had played such significant roles. And he saw this as in part a matter of going after that

world and not the six actual Marxists on campus.

JW: And of course, Eisenhower was the first time the Republicans had been in power since FDR had

been elected in 1932. The New Deal had been triumphant. FDR served four terms, then his Vice

President Truman served one, then the Republicans were back and they wanted to reopen the question

of the New Deal, which had dominated American society for much of the lifetime of a lot of Americans

at that point. So the New Deal was very much on the agenda of the Republicans at the first moment that

they could try to overthrow it.

BG: That’s right. And in that first Eisenhower election, it wasn’t just that Eisenhower was elected, it’s

that Congress became Republican for the first time. And actually only quite briefly by 1954, the House

had gone back to being a Democratic majority, which it would stay until 1994. So for 40 years we had a

Democratic majority in the House, a different world of politics, certainly than people are used to today.

But that moment in the early and mid 1950s was a moment of really fierce partisan contest and

controversy.

JW: And you say that in the face of McCarthyite attacks on the university in the fifties, Hofstadter

worried that his fellow academics were no good at defending themselves in the real world of political

power. What did he say about that?

BG: I think I mentioned already how much of the book is actually about that kind of critique. He felt that

the left in particular was much more interested in first of all its own internal factional controversies, was

much more interested in its own purity and in feeling like it had the righteous position, rather than

coming up with a set of ideas and coalitions that were going to make it really effective in American

politics and effective at defending what it was that he thought was so important about intellectual life

and the place of the university in a democracy.

JW: So we can see many ways in which Trump is following a time-worn Republican strategy in attacking

Harvard and universities in general. But there are some parts of Trump’s campaign that are completely

new and extremely dangerous. The one that seems to be first on the list is the massive cuts in research

funding–obviously number one. Never before has a president cut funds for curing cancer.

BG: One of the strange things about this moment is that it is the dismantling of that earlier moment. So

that part of what ended up happening in the 1950s is that the broader context changed. The Soviets put

Sputnik up into the sky and Americans got worried. And so even though the fifties were in some ways

this moment of anti-intellectualism, as Hofstadter put it, they became a moment where there was a very

fast turn toward science in particular, toward these new structures of federal funding, toward the

expansion of higher education. And so when we look back on that now, many people see the moment

that he’s writing actually as the golden age of American higher education. And it really is the roots of the

system of federal funding, particularly for science, that is now being dismantled in so many ways.

JW: And Trump says his goal in cutting billions of scientific and medical research funds is to punish

Harvard and other schools for failing to protect Jewish students from antisemitism on campus. That was

not exactly a theme of Joe McCarthy’s.

BG: That was not a theme of Joe McCarthy’s. That is a hundred percent true!

JW: And while Trump says he wants to protect Jewish students, that goes along with this attack on

diversity, equity, and inclusion, and his demand that universities abolish DEI policies as a condition of

receiving federal funds. Now that of course is an attack, first of all, on admitting non-white students. The

idea that universities should serve white students was really never made explicit in the fifties in the way

that Trump is doing it now with a campaign against DEI.

BG: I do think that the question of who deserves access to higher education in this country, whether

you’re talking about race, whether you’re talking about gender, whether you’re talking about class, and

then within the world of higher education, who deserves access to the very top, the most elite

institutions, we are seeing particular variations on that struggle right now. But that fundamental set of

questions has been very contested and is only becoming more contested as higher education in some

sense becomes more important in American life.

One of the reasons that we are seeing this debate about higher education is in part that over the last 20

or 30 years, so many people have been told that it’s the only way to access the American good life. And

so it’s in some sense, no surprise that the question of who can afford it, who has access to it, what’s

taught in these institutions would become a political issue. So we are seeing a particularly intensive, and

in many ways quite troubling variation on that now. But that has been a really important question for a

long time. And it’s fundamentally not only a question about universities and what they do, but it’s a

question about the broader society and what it values and how it understands itself as a social system.

JW: One of McCarthy’s goals was to purge people with radical ideas from government employment.

And this was something actually that Democrats went along with in some respects. And McCarthy did

get thousands of people fired from government jobs on the grounds that they were radicals–also on the

grounds that they were gay. Trump, of course, has fired many more people from government jobs, but

just on the grounds that they had government jobs. There were no individual loyalty hearings, case by

case, of the kind that we associate with McCarthyism. And that seems to be a significant difference.

BG: I think the scale of what’s happening now is quite different, but from the moment that the New

Deal was created, its political opponents had a critique of the bureaucracy of the administrative state,

first of all, as itself being undemocratic, as being full of unaccountable bureaucrats, as being full of

experts who only talked to each other and weren’t responsive to politics. And in particular for

Republicans that the executive branch, the administrative state, was a kind of boondoggle for liberal do-

gooders who were going to vote Democratic. So it is true that the scale of what we’re seeing now looks

quite different, but that fundamental critique, which is so present in our own time, has a pretty deep

history.

JW: In your piece in the New York Times, you give Hofstadter the last word.

BG: I love this quote because it is a sort of a ‘two cheers for intellectuals’ kind of quote, in which he is

both trying to affirm with everything he has and everything he holds dear, how important education

intellectual life in the freest possible way is to any democratic society, while also acknowledging that his

friends and comrades should maybe engage in some of the critique and self-critique that they’re so

happy to apply to other people. So I just really loved this quote, which I will read to you.

This is from Hofstadter: ‘I have no desire to encourage the self-pity to which intellectuals are sometimes

prone by suggesting that they have been vessels of pure virtue set down in Babylon. But one does not

need to assert this, or to assert that intellectuals could get sweeping indulgence or exercise great power,

in order to insist that respect for intellect and its functions is important to the culture and the health of

any society.’

JW: Richard Hofstadter gets the last word. Beverly Gage’s essay on Richard Hofstadter’s book, ‘Anti-

Intellectualism in American Life’ is titled ‘The American University is In Crisis, not for the first time.’ It

appeared in the New York Times, where it’s available online. Bev, thanks for this piece, and thanks for

talking with us today.

BG: Thanks for having me back.