Exchange: Orlando Figes & ‘The Whisperers’ Exchange: Orlando Figes & ‘The Whisperers’

London Re Peter Reddaway and Stephen F. Cohen’s June 11 “Dishonoring Stalin’s Victims,” about my 2007 book The Whisperers: in a book as large and complex as The Whisperers unintended errors are not unusual. Normally they are dealt with by a writer and his publisher without the intervention of the press or other academics given access to such private correspondence. I reject the insinuation that I used a political smokescreen to conceal shoddy scholarship. The first I heard of Dynastia’s concerns was on April 15, 2011—two years after my one and only comment about politics on the cancellation of the first contract with Atticus in March 2009. In their letter Dynastia drew my attention to about a dozen “factual inaccuracies” and “misrepresentations.” On close examination the alleged faults turned out to be errors of translation, matters of interpretation or derived from Memorial’s own sources—leaving a handful of genuine errors in a book based on thousands of interviews and archival documents. The Whisperers was always going to be a complicated book to translate into Russian. In anticipation of the problems we might encounter, I prepared a 115-page memorandum for the translators but never heard from them. I was not consulted on the translation. I regret any mistakes. It was never my intention to cause offense, to “insult the memory” of anyone or to misrepresent the history of any family included in the book. Nor have I “invented” things. On April 18, 2011, I replied to Dynastia addressing their concerns, pointing out some of the confusions in their translations and offering to make any “revisions” they considered necessary. I received no reply. The misquotation of Natalia Danilova resulted from the accidental substitution of my annotated file for the original transcript. I corrected the error as soon as I was made aware of it. Mikhail Stroikov’s daughter referred in an interview to an “Uncle Boria,” who worked in OGPU. This was the source of my mistake, as Memorial’s researchers suggested. I reject the accusation that I “invented facts” for “dramatic purposes.” According to Memorial’s sources, Dina Ioelson-Grodzianskaia was employed as an “agronomist” and a “specialist” when she was a prisoner—in Solzhenitsyn’s terms, enough to justify describing her as a “trusty”—although I wrote sympathetically about her as a victim of the Gulag. In my letter to Dynastia I offered to withdraw any words that might have caused offense. I am grateful to Memorial, who, three years after The Whisperers was published, gave me access to the valuable archive that forms the basis of Just Send Me Word. It is wrong to suggest that I have misused the “Note From Memorial.” Its inclusion in my book was a condition set by Memorial and one I was anxious to honor. ORLANDO FIGES Reddaway and Cohen Reply Washington, D.C.; New York City In his reply to our article, Orlando Figes presents readers with still more misrepresentations of the truth. Figes now claims that Dynastia, in informing him that it was canceling the contract to publish a Russian edition of The Whisperers, cited only “about a dozen ‘factual inaccuracies’ and ‘misrepresentations.’” To clarify the matter, Dynastia has allowed us to quote the letter to which Figes refers. This letter, dated April 6, 2011, draws attention to numerous errors and misrepresentations in just a few sample fragments of The Whisperers (not the entire book, as Figes would have Nation readers believe), and says that “after revising several chapters we had to stop.” Figes is also dissembling by implying that the “alleged faults” were mostly not his doing but those of Memorial itself, his translators or merely “matters of interpretation.” This too is untrue and, even more, a slur on those dedicated, highly professional Russians. In truth, the chief researcher of Memorial, which had conducted the Russian-language interviews on which the book was based, wrote to the head of Memorial: “I wept as I read it and tried to make corrections…. I gave only a few examples, but the entire text is like this…. It’s even difficult to choose examples; they appear throughout.” Consider Figes’s attempt to explain away two of the examples given in our article. It was Figes alone who alleged that the imprisoned Stroikov had “the support of the political police,” for which there is no evidence at all. And it was Figes, not Solzhenitsyn, who accused Ioelson-Grodzianskaia of “collaboration” with Gulag authorities, which the Memorial researcher characterized as “a direct insult to the memory of a prisoner.” These kinds of distortions, which turn tragic history into melodrama, explain why Dynastia wrote in the letter canceling the contract with Figes that if published in Russia, The Whisperers “would definitely provoke a scandal.” As for a “political smokescreen to conceal shoddy scholarship,” this is Figes’s insinuation, not ours. He made the wholly implausible allegation of “political pressure” in 2009, when his first Russian publisher dropped the book, and he has never withdrawn it—certainly not in his reply to us or in the London Guardian’s front-page report (May 24) on our article, in which he repeated his suggestion “that politics was involved” and astonishingly added that the second cancellation of the book, in 2010, was “pre-publication censorship.” This too impugns the integrity and courage of honorable Russians—the publisher, funding foundation and Memorial alike. Finally, Figes falsely implies that he still has Memorial’s support. As one of its veteran leaders wrote in a statement in April, “In the future, we do not want to link his name with that of Memorial.” PETER REDDAWAY, STEPHEN F. COHEN Clarification Dana Frank’s “Honduras: Which Side Are We On?” [June 11] included a portion of a statement from Miguel Facussé, owner of Grupo Dinant. Here is Facussé’s complete response to a question about what role his security guards played in a November 15, 2010, incident at the El Tumbador farm in which five campesinos were killed: “The group [of campesinos] informed the security guards on site, who were employees of a third-party provider, that they would open fire on the guards and other workers present if they did not abandon their posts and allow them to seize the land within five minutes. Many of the campesinos, armed with illegal weapons, including AK-47s, opened fire on the guards and workers, who were forced to defend themselves. Unfortunately, four campesinos were killed in the gun battle, while a fifth one was found the following day near the plantation. While all the victims were shot with AK-47s, none of the guards were carrying such weapons, as they only carry revolvers and shotguns.” Contrary to Facussé’s claims, two witnesses have testified to human rights observers that the campesinos were unarmed and that Grupo Dinant security guards used AK-47s to ambush and kill the campesinos; one testified that an M-60 was used as well. According to a fact-finding report by FoodFirst Information and Action Network, among other groups, the Honduran government did not release ballistic reports for the arms confiscated from the security guards. No investigation or prosecution of the killings was concluded by Honduran authorities.

Jun 13, 2012 / Orlando Figes, Peter Reddaway, and Stephen F. Cohen

Letters Letters

About NATO, the Postal Service, Gil Scott-Heron and Obama’s record

Jun 5, 2012 / Our Readers

Letters Letters

Responses to Alexander Cockburn, John M. Barry, Katha Pollitt and Jane McAlevey, and another Italian lesson

May 29, 2012 / Our Readers

Letters Letters

On Dorothea Lange, Michael Harrington, Earth Day and solitary confinement

May 22, 2012 / Our Readers and Mark Hertsgaard

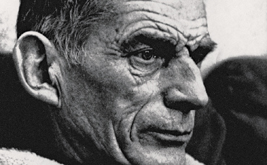

Love, Sam: On the Letters of Samuel Beckett Love, Sam: On the Letters of Samuel Beckett

Samuel Beckett wants you to have a less bad day.

May 16, 2012 / Books & the Arts / Aaron Thier

Letters Letters

They Speak Bornholmsk, Don’t They? Vancouver In his review of Norman Davies’s Vanished Kingdoms [“Shelf Life,” April 30], Thomas Meaney referred to the “island of Bornholm off the Danish coast, where the Burgundians may have established an early kingdom.” Actually, Bornholm is a Danish island off the Swedish coast, and it’s closer to the Polish and German coasts than to the Danish coast. ROBERT RENGER Abolitionists: First Human Rights Activists? Ypsilanti, Mich. In “Of Deserts & Promised Lands” [March 19], Samuel Moyn asserts that “abolitionists almost never used the idea of rights, activated as they were by Christianity, humanitarianism or other ideologies.” Moyn needs to read the American abolitionists to see how wrong this is. David Walker’s Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World (1829) faults Jefferson for denying rights to slaves that he proclaimed for others. Walker, one of the most influential black abolitionists, also embraced Christianity, but his faith was not in conflict with his demand for full rights for the enslaved. Claiming equal rights was central to Walker. A few years after Walker’s Appeal, William Lloyd Garrison, the most influential white abolitionist, wrote the Declaration of Sentiments for the 1833 founding meeting of the American Anti-Slavery Society. It said, “The right to enjoy liberty is inalienable” and “Every man has a right to his own body—to the products of his own labor—to the protection of law—and to the common advantages of society.” The abolitionist movement was based on demanding equal rights. Abolitionists claimed equal rights for blacks and defined slavery as inherently a violation of rights. The abolitionists deserve credit for helping to create the very idea of universal human rights, even if their century lacked a system of international law in which to make their case. MARK D. HIGBEE Moyn Replies New York City It is well-known—and people are turning up more evidence today—that the language of rights was sometimes used by American abolitionists, especially during a brief period in the 1830s. The phrase “human rights” even served as the title of an abolitionist magazine. That doesn’t mean, of course, that it was the dominant framework for abolitionism, then or ever. And not only was the American story complex; it was just part of the vast story of the agitation against global slavery (in the British sphere, rights talk had less traction). In any event, as Mark Higbee correctly points out, the international law of the era never conferred rights, let alone “human rights,” on Africans, including in the episode Jenny Martinez recounts in her interesting book. SAMUEL MOYN Getting on the Good Side New York City In “Faces out of the Crowd,” his March 26 review of the Renaissance portrait show at the Met, Barry Schwabsky wonders why left-facing profiles are much more common than right-facing ones and calls it a “mystery” that this goes “unmentioned.” Would that the critic would try it himself! Had he done so, he might have noticed what most draftsmen know—and what the Renaissance art historian David Rosand observes in Drawing Acts about a group of profile drawings by the (left-handed) master Leonardo da Vinci: “All the heads face to the right, as we might expect of a left-handed draftsman: the natural way to draw a profile is from within, the hand moving inside the head, internally generating the curving contour outward, from the wrist.” More artists—more people—are right-handed; thus, they begin the contour from upper right, which results in a left-facing profile. DEBORAH ROSENTHAL

May 15, 2012 / Our Readers and Samuel Moyn