When the World Became a Huge Penitentiary When the World Became a Huge Penitentiary

An eloquent portrait of underground life among the undocumented and the damned of the earth.

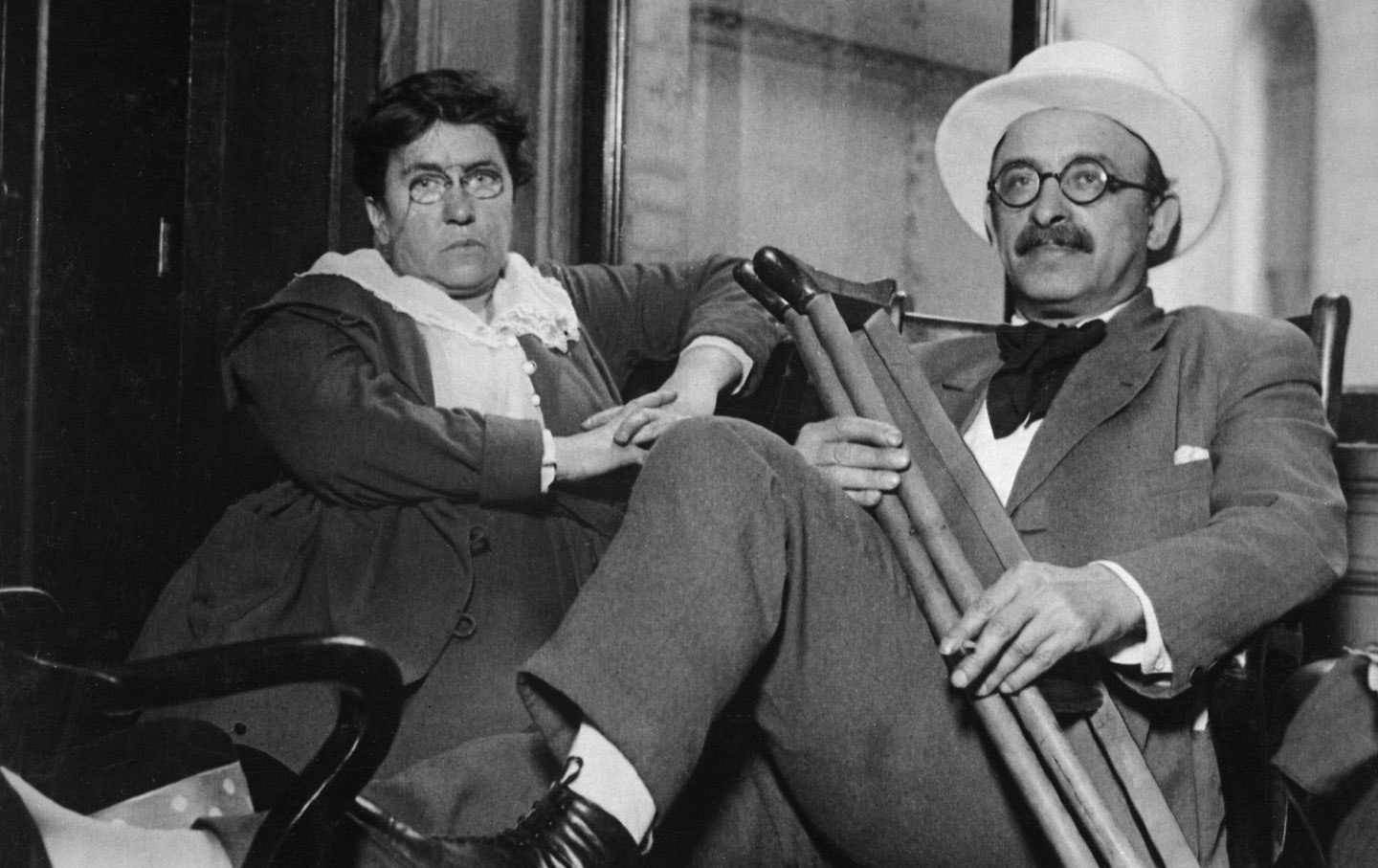

Mar 23, 2015 / Feature / Emma Goldman and Vivian Gornick

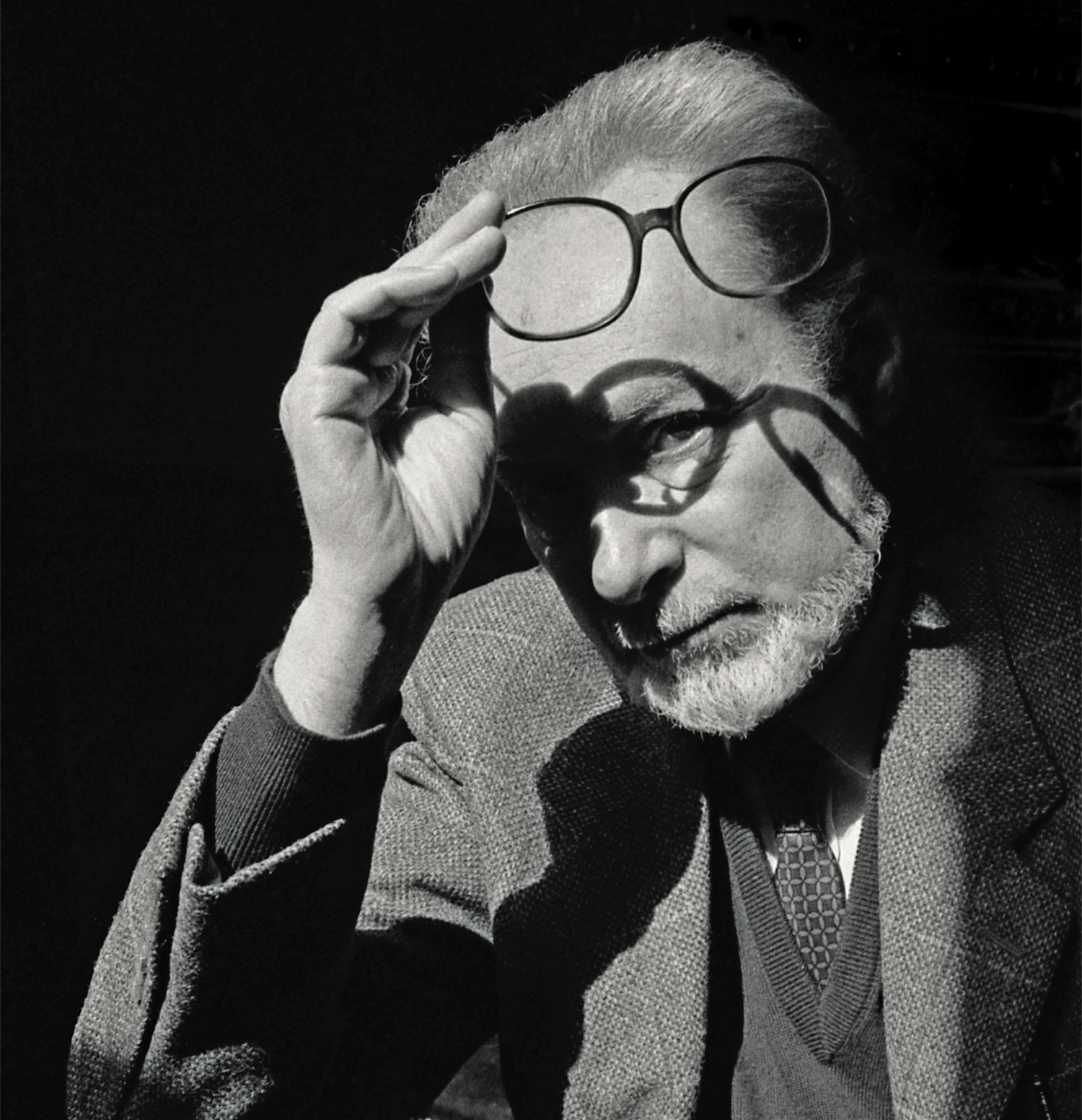

Without Respite Without Respite

Seeing not a person but a thing was the crime of crimes for Primo Levi.

Nov 25, 2013 / Books & the Arts / Vivian Gornick

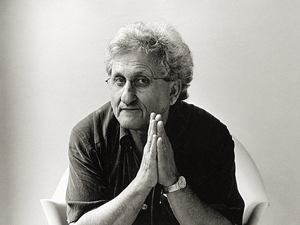

Darkness Lit From Within: On A.B. Yehoshua Darkness Lit From Within: On A.B. Yehoshua

The soul-destroying weariness in A.B. Yehoshua’s stories seems as old as time itself—and unique to contemporary Israel.

Mar 6, 2013 / Books & the Arts / Vivian Gornick

A Deliberate Pace: On Rachel Carson A Deliberate Pace: On Rachel Carson

On a Farther Shore captures the conservationist’s deep sense of geologic time and the forces of evolution.

Feb 19, 2013 / Books & the Arts / Vivian Gornick

A Double Inheritance: On Margaret Fuller A Double Inheritance: On Margaret Fuller

A nineteenth-century feminist's exceptional life.

Apr 3, 2012 / Books & the Arts / Vivian Gornick

Emma Goldman Occupies Wall Street Emma Goldman Occupies Wall Street

This is the second time in living memory that an American movement protesting social injustice has embraced her.

Dec 7, 2011 / Vivian Gornick

Starting out in Seattle: On Jonathan Raban Starting out in Seattle: On Jonathan Raban

Jonathan Raban has made a persona out of the self that feels nowhere at home.

Nov 16, 2011 / Books & the Arts / Vivian Gornick

History and Heartbreak: The Letters of Rosa Luxemburg History and Heartbreak: The Letters of Rosa Luxemburg

Rosa Luxemburg wanted it all: books and music, sex and art, evening walks and the revolution. Her lover, Leo Jogiches, told her this was nonsense.

Apr 13, 2011 / Books & the Arts / Vivian Gornick

Exchange Exchange

Vivian Gornick on James Wood New York City William Deresiewicz's attack on James Wood strikes the common reader--inclined neither to anoint nor denounce--as extraordinary, so extreme is the avalanche of accusatory prose that is being leveled at a critic of comparable age, education and ability ["How Wood Works," Dec. 8, 2008; "Letters," Jan. 5]. I happen to agree with Deresiewicz on every point he makes about Wood's criticism: it is narrowly aesthetic; it does worship at the wrong literary altar; and increasingly it sounds as though it is coming from a world other than the one the rest of us are squirming around in (herein lies its true weakness: that the work is not grounded in the emotional undercurrents of its own moment). Yet James Wood, champion of the now painfully inadequate realist novel, is indeed the most celebrated critic of this decade as well as the one before. Instead of writing thoughtfully about this singular development, Deresiewicz goes on the warpath, confusing symptom with cause so badly that by the end of the piece his subject begins to seem an innocent bystander. Wood is charged with being an unhappily lapsed Christian who displaces onto novel-writing an inappropriate demand for moral (i.e., spiritual) accountability; at the same time, Deresiewicz praises the famous New York critics of some generations past for regarding literature in relation to politics and society. Yet Lionel Trilling was every bit as much a sermonizer as is Wood, declaring repeatedly that the novel had the sacred duty to serve the idea of the moral imagination because it alone could save us from ourselves. In fact, Wood and Trilling are almost exactly the same kind of conservative critic, the major difference between them being that Trilling had the edge because he was writing in a time when literary culture flourished: women and men read widely if not deeply--The Liberal Imagination sold a remarkable 70,000 copies when it was published in 1950--and looked happily to elegant criticism to cast light on the way they were living their lives. There were, however, even then, readers who looked upon Trilling as an aesthete and a moralizer and did not at all love his take on world, self or literature; for them, he never spoke persuasively to what Wallace Stevens called "this iron solitude"--the penetrating psychological truths behind modernist despair. No matter. Trilling's convictions were the middlebrow convictions of his time--and he linked them brilliantly to novel-reading. Today, literary culture is not only not flourishing, it is on the defensive: very few read (or for that matter, write) to save their lives, as people did fifty years ago, and no critic, of whatever stripe, can be immune from the knowledge that he or she is working at a moment when the very act of holding a book in one's hands seems like it might soon become an artifact. Yet, as Randall Jarrell once said, whether we know it or not, without literature human life is animal life--and Wood is the critic who still takes this proposition most to heart. As Deresiewicz acknowledges, Wood goes on writing about literature "as if our souls depended on it, which for any serious reader, they do." And that, finally, is why he is celebrated. It is not that Wood is necessarily smarter, or even better read, than half a dozen others--and God knows, his sense of mission is misplaced--it is simply that he writes about literature with unequaled passion in a time and place when the drive to make storytelling art seems imperiled. The content of his criticism may indeed be retrograde, separated as it is in so many ways from the actuality of our shared experience--and for this reason will probably not stand any test of time--but for now, his work is a holding action: a kind of bridge between an era in which the reading world was saturated in self-confidence and a time when it may yet again believe in itself. Wood's readers--the same people who would have been Trilling's readers--do not need to engage with what he is actually saying as much as they need to rhapsodize over the gorgeousness of his endlessly adjudicating prose: it reminds them of what they are most in fear of losing. Seen in this light, he hardly qualifies as the enemy Deresiewicz is bent on shooting down. To the contrary: he is one of our own, struggling to deliver a message, perhaps to the wrong base but still to a base on our side of the divide. VIVIAN GORNICK Deresiewicz Replies Portland, Ore. Vivian Gornick agrees with every point I make about James Wood; she just doesn't want me making them in public. She wants to see a revival of literary culture, but not at the cost of actually having a literary culture. I did not charge Wood with being an unhappily lapsed Christian who looks to literature for moral accountability; I charged him with being a proud apostate who looks to literature for metaphysical certainty. Wood's problem is precisely that he has no interest in the way literature bears on moral questions--that is, on personal or social or political ones. He isn't as much of a "sermonizer" as Trilling; he isn't a sermonizer at all. But of course, Trilling wasn't a sermonizer either. He didn't affirm the middlebrow convictions of his time; he exposed them to relentless scrutiny by uncovering the ways that literature called them into question. He probably would have greeted Gornick's talk of "the penetrating psychological truths behind modernist despair" as an example of what he called "the modern self-consciousness and the modern self-pity." But why are we even talking about Trilling? I named five of the New York critics and gave him no more space than most of the others. Trilling, however, has long since been reduced to a toy soldier in the culture wars, the last of the Dead White Men. No wonder it is so difficult to find an intelligent appraisal of his work, let alone an honest one (Stefan Collini's December 8 piece in this magazine being a rare exception). I did not acknowledge Wood's passion as a critic: I announced it, I celebrated it, I trumpeted it. I spent three paragraphs near the start of my review extolling his virtues, and I reaffirmed them in the very last sentence. In fact, I seem to have a much higher opinion of his work than does Gornick, who values it only for its passion. But passion alone is not enough to justify Wood's criticism, or anyone else's. The ideas that travel on the winds of that passion matter as well. Yet Gornick believes that we "do not need to engage with what [Wood] is actually saying." Don't need to engage with what he is actually saying! What a brave conception of intellectual discourse. But that, apparently, is my sin: that I take Wood seriously enough to criticize him--precisely what Gornick admires in Wood's treatment of literature itself. His passion is good. My passion is bad. My passion means that I am treating Wood like an "enemy" whom I am "bent on shooting down." (If you really want to see a critic "on the warpath," read Gornick's essay on Saul Bellow and Philip Roth in the September 2008 issue of Harper's.) For Gornick, cultural life is a kind of political struggle, complete with "sides" and "enemies" and "bases" to whom the right "message" must be "delivered." We must show solidarity at all cost, even if it means betraying every one of our principles. Taking another critic to task is akin to attacking a fellow Democrat, and Wood becomes the Joe Lieberman of the Reading Party, someone we are obliged to embrace simply because he caucuses on our side of the aisle, even though we don't agree with a single thing he says. But culture isn't about being on the right team, or any team. There is no "us." With a remarkable lack of self-consciousness, Gornick employs the very rhetorical device for which Trilling was most consistently criticized, the use of the first-person plural. Yet when Trilling spoke of what "we" believe or do, he used it as a form of collective self-criticism: "we" the self-flattering liberal middle class. Gornick uses it, instead, as a form of self-flattery: "our own," "our side"--the blessed "us," heroically holding the bridge against the barbaric "them." Nothing will enfeeble a literary culture more effectively than this kind of tribalism. You don't protect criticism (or art) by not criticizing it; you kill it. Culture isn't a tea party, or a political party. It is a debate: loud, passionate, even, at times, intemperate. If you really care about reading--or writing--you care about it enough to want it done the right way. "Passion" doesn't mean approving of everything that exhibits passion. It means having standards and being willing to say when those standards are being met and when they are not. And the person who understands this better than anyone is James Wood. WILLIAM DERESIEWICZ

May 20, 2009 / Vivian Gornick and William Deresiewicz

Letters Letters

ISAAC B. SINGER & G.G. Shaker Heights, Ohio A half-century ago, I discovered Graham Greene and Isaac Bashevis Singer at about the same time. I got the feeling that I was reading two interchangeable novelists, each describing the same predicament, one from a Jewish vantage point, the other Catholic. I must have read The End of the Affair and The Magician of Lublin at about the same time. Both describe "the problem" exquisitely well, the agonies of lost faith, love and even hope. Both were equally unable to resolve the crises except by making a kind of shaky nod to their respective traditions. In The Magician of Lublin, Yasha the magician, traversing the well-trodden ground of the desired shiksa, the mendacity of business whether gangster or upright and the fall from faith, finally resolves it all by bricking himself up and becoming Yasha the penitent. Thus it was that I was stunned to read Vivian Gornick's review of Florence Noiville's biography of Isaac Bashevis Singer ["Before the Law," March 5] and find a recap of those long-ago thoughts. I have no idea whether the comparison has been made elsewhere. I'd like to think it's just Ms. Gornick and me. HAROLD TICKTIN Savannah I have read a lot of Isaac Bashevis Singer's stories and always end up with a feeling of utter despair. What I have always kept from Singer is a comment he made at the start of his story "Shosha": His people had lived in Poland for almost a thousand years yet spoke hardly any Polish. Their lives were regulated by two dead languages, Hebrew and Aramaic, and all thought was devoted to knowing the rituals appropriate for a temple that had ceased to exist 1,900 years earlier. This is the culture Arnold Toynbee called a fossil, for which he was attacked as an anti-Semite. But any attempt to make this fossilized culture meaningful is doomed to failure. Singer knew this. NORMAN RAVITCH New York City Vivian Gornick writes that Isaac Bashevis Singer "never allowed his work in book form to be published in Yiddish. Everyone in the world read him either in or from the English translation." She is mistaken. While it is true that some of his Yiddish works have never been published in book form, the YIVO library has ten books of his in Yiddish--five novels and five collections of short stories. Der sotn in goray was published in Warsaw in 1935. The last original edition in his lifetime, according to our catalogue, was Der bal-tshuve (The Penitent) in 1974. PAUL GLASSER YIVO Institute for Jewish Research GORNICK REPLIES New York City Paul Glasser is, of course, right. There are many Singer stories and novels in Yiddish. What I meant to say, but said badly, is that it was after Singer was "discovered" by his American translators in the mid-1950s that he stopped all publication of his work in Yiddish in book form. Except for the stories that appeared in the Yiddish newspaper the Forward, from then on all of Singer's work appeared in English. VIVIAN GORNICK ANTI-IMMIGRANT AD AROUSES IRE Los Angeles I received your May 14 issue just after watching the LAPD attack immigrants' rights demonstrators. When I saw the advertisement on the back cover I was taken aback. Then when I heard one of your writers, Max Blumenthal, on Democracy Now! exposing the close ties between the anti-immigrant movement and white supremacists, I was outraged. A short Google search of the Coalition for the Future American Worker (CFAW) showed it as a creation of the Federation for American Immigration Reform and the American Immigration Control, which has ties to the white supremacist Pioneer Fund. The ad made its pitch using an African-American "civil rights leader," who by the way was Jeb Bush's frontman for the attempt to privatize Florida's schools through the use of vouchers. CFAW is not simply an organization concerned about H-1B visas, and you should know that, so why run that advertisement--which shows tacit approval of CFAW? What's next: ads from Ward Connerly's anti-affirmative action group, the American Civil Rights Institute? ELAN DELGADILLO The Nation's position on immigration is not that of CFAW. Over the past 140 years of publishing we have printed more than 2,700 pieces discussing immigration issues from a progressive perspective, including, most recently, a February 26 cover story, March 5 and May 7 editorials and an editorial on page 8 of this issue. The May 14 ad is not an endorsement of CFAW; we hope readers understand that an ad on immigration (or any topic) does not imply the magazine's endorsement of the ad's content. In 1979 The Nation established its advertising acceptability policy (see www.thenation.com/mediakit/policy). It says, in part: "We accept [advertising] not to further the views of The Nation but to help pay the costs of publishing. We start, therefore, with the presumption that we will accept advertising even if the views expressed are repugnant to the editors...." Publisher emeritus Victor Navasky recently wrote: "I, for one, approach all advertisers (in The Nation or anywhere else) with suspicion, and we pay our readers the compliment of thinking they do, too. This is especially true of...GM, GE, [Fox News] and the many other corporate advertisers The Nation has carried over the years and whose messages we regularly attack in our editorial columns. If we allowed the advertisers to influence editorial content, that would be prostitution, but we don't." We regret that some ads offend our readers. Ads pay our bills. They do not reflect our editorial position. --The Editors PALESTINIAN POETS Yellow Springs, Ohio Poetry editor John Palattella has the soul of one who truly understands anguish. His review of three Palestinian poets' work, "Lines of Resistance" [Feb. 19], so spoke to me that I kept rereading paragraphs to make certain of the poets' lines. I also underlined such phrases of Palattella's prose poetry as "escape from the prison of nationalism"; "open-air cell of sadness, melancholy and absurdity"; a style that "flowers furiously into a bittersweet and melancholy song"; "the incantatory music quickens"; "a sadness deeper than sadness." As one who was raised a Protestant Zionist Evangelical, I grew out of it from reading and hearing such Jewish critics as Balfour Brickner, I.F. Stone, Israel Shahak and Michael Lerner. You are to be commended for steadfastly continuing the critique of US-Israeli policies. GORDON A. CHAPMAN Houston John Palattella reviews Mahmoud Darwish's poetry in English translation and tries to define Darwish's standing in the world of Palestinian poetry. This leaves the reader with a restricted view of Darwish's body of work. Palattella painted Darwish with the brush of the "heroic" and "defiant" poet of "resistance." The history of the evolution of Darwish's poetry is too versatile and encompassing for such a limited description. The poems that defined Darwish's stature in modern world poetry have been of the epic, personal, love, theatrical, conversational, witness, diary poem forms, to name some. Darwish's eminence as a modern poet crossed the borders of Palestine long ago. The universality of his poems, especially in the 1980s and beyond, cannot be reduced to a description of what his early poems were. HANA EL SAHLY WELCOME TO THE 'COUNTRY' CLUB Geneva, Switzerland Having served twenty years with the UN, I found Perry Anderson's review of books on the UN ["Made in USA," April 2] particularly incisive but somewhat wanting on three points. First, while Kofi Annan deified his position, the UN Secretary General is nothing more than his job description in the UN Charter, namely the "chief administrative officer of the organization." Hence his function is to administer, a job Annan did singularly badly. Everything else is smoke, albeit smoke that sold well. Second, writing that Ban Ki-moon's election "required Chinese assent" is disingenuous, as all Secretary Generals require Chinese assent, not to mention that of the other four permanent members of the Security Council. Finally, the UN is a club. One member, the United States, pays about 23 percent of the dues. Three members--the United States, Germany and Japan--pay some 50 percent. Twelve members pay some 80 percent, which means that the remaining 180 members pay less than 1 percent each, on average. The UN will cease to be a tool of the West and a forum for the rest the day the costs are more evenly spread--an unlikely event that would probably make for an even worse UN. ALESSANDRO CASELLA YES I SAID YES I WILL YES... Philadelphia Stephen Gillers's "Free the Ulysses Two" [Feb. 19] notes lawyer John Quinn's lack of enthusiasm in his defense of Ulysses as published in The Little Review in 1921. Quinn thought the case was hopeless. It is true that during the 1920s, the NY Society for the Suppression of Vice did begin to lose obscenity cases when a book's literary value was established. However, when it lost, as with the case Gillers mentions regarding Lawrence, Freud and Schnitzler, the Vice Society had a grand jury indict the publisher of those three authors on the same charges. After two and a half years of lost time and money, the publisher had to give up the fight. Not only had Ezra Pound expurgated Ulysses passages before the "Ulysses Two" printed excerpts; the book was under special customs surveillance as subversive, probably because The Little Review had published anarchist writers. If Pound himself thought Joyce's frankness regarding defecation, masturbation and intercourse hopeless, it is no wonder Ulysses was not the right book to challenge the era's moral entrepreneurs. It took the genius, and connections, of Morris Ernst to de-censor Ulysses, in 1934. The influence of the father-in-law of Joyce's son, the wealthy stockbroker Robert Kastor, in preparing the way for this event is an imponderable. JAY A. GERTZMAN, author Bookleggers and Smuthounds: The Trade in Erotica, 1920-1940

May 9, 2007 / Our Readers and Vivian Gornick