Here's where to find podcasts from The Nation. Political talk without the boring parts, featuring the writers, activists and artists who shape the news, from a progressive perspective.

Crossing the abortion borderland from Texas to New Mexico: Amy Littlefield describes the heroic work being done in both states to provide help to people seeking abortions, one year after the repeal of Roe, and reports on the new obstacles being raised by anti-abortion forces.

Also on this episode of Start Making Sense, 20 percent of likely Democratic voters tell pollsters they support Robert F. Kennedy Jr. in his primary challenge to Joe Biden. Joan Walsh joins the podcast to tell the story of her history with Kennedy and his anti-vax crusade.

Advertising Inquiries: https://redcircle.com/brands

Privacy & Opt-Out: https://redcircle.com/privacy

Crossing the abortion borderland from Texas to New Mexico: Amy Littlefield describes the heroic work being done in both states to provide help to people seeking abortions, one year after the repeal of Roe, and reports on the new obstacles being raised by anti-abortion forces. Also on this episode of Start Making Sense: 20 percent of likely Democratic voters tell pollsters they support Robert F. Kennedy Jr. in his primary challenge to Joe Biden. Joan Walsh joins the podcast to tell the story of her history with Kennedy and his anti-vax crusade.

Jon Wiener: From The Nation magazine, this is Start Making Sense. I’m Jon Wiener. Later in the show: 20 percent of likely Democratic voters tell pollsters they support Robert F. Kennedy Jr. in his primary challenge to Joe Biden. Joan Walsh will report on her history with Kennedy and his anti-vax crusade.

First, the battle on the abortion borderlands between Texas and New Mexico one year after the repeal of Roe. Amy Littlefield has our report—in a minute. [BREAK]

A recent USA Today poll shows that 80 percent of Americans oppose a nationwide ban on abortion. That includes 83 percent of Independents and even 65 percent of Republicans, while only 14 percent support a nationwide ban. Nevertheless, one year after the repeal of Roe v. Wade, abortion is banned in 13 states, leaving large regions of the country without abortion care. For an update, we turn to Amy Littlefield. She’s The Nation’s abortion access correspondent, and she’s been traveling through what she calls the abortion borderland in Texas and New Mexico to assess the damage, and to see how people seeking abortions and abortion rights activists and providers are doing. Amy, welcome back.

Amy Littlefield: Thanks so much for having me back, Jon. It’s great to be here.

JW: You open your report for The Nation on the abortion borderlands at a North Texas airport, where the Rev. Erika Ferguson meets a group of people who need abortions. Tell us about that.

AL: Reverend Erika Ferguson is an interfaith minister. She’s been in the movement for reproductive rights and justice for many years, and she has had two abortions herself, one when she was 14, one when she was 18. She sometimes talks about her abortions from the pulpit. She is a Black woman. She understands the risk of criminalization, and yet she has been willing to take this very brave decision to shepherd each week a new group of strangers who live in Texas who need abortions, and she takes them to New Mexico where they can get abortion care that is banned in their home state.

JW: Texas is the epicenter of efforts to punish people who help others get abortions. What did Erika Ferguson tell you about the risks she faces?

AL: She told me that as a Black woman living in the United States of America, the risk of criminalization is the air she breathes. It’s not confined just to these trips, but it’s of course compounded by the fact that Texas has three different anti-abortion laws in place, including one that bans abortion at around six weeks and allows people to sue with civil lawsuits over anyone who aids or abets in abortion, and then including of course, criminally banning abortion.

Texas is also the epicenter of efforts to use creative new strategies to break new ground in trying to stop anyone who helps someone else get an abortion. We saw this earlier this year when Jonathan Mitchell, the Texas anti-abortion strategist, filed a lawsuit accusing three people who helped their friend get an abortion. They helped her get access to abortion pills. She was going through a divorce and needed access to an abortion, and her ex-husband found out about it, and is suing these friends for over a million each and accusing them of murder.

These are the types of strategies that we’re seeing coming out of Texas to try to stop anyone from helping their friend or their loved one, or in Reverend Erika Ferguson’s case, total strangers. She told me that she’s motivated to make these trips and to take the risk because of the compassion and care that she received at the clinic when she had her abortions as a teenager. That animates her decision to do this work.

What she does is she meets these women at the airport. She introduces herself by explaining her story, by talking about her abortions. She told me even though she’s a minister, she doesn’t talk to the women directly about God, that the way her ministry shows up is in her care and it’s in the words that she says to them, which is, “You are going to be safe. You are going to be cared for.” For many of these travelers, they haven’t left the state before. They haven’t flown before. Some of them have been teenagers. Some of them have been rape victims. Some of them have been moms who leave behind kids of all ages and fly with this group of strangers.

They arrive in Albuquerque, New Mexico. They’re met with volunteers, taken to a clinic where they receive their abortions, and then they recover in the headquarters of the New Mexico Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice. This is a remarkable faith-based organization that’s been around since the ’70s, and they are greeted with homemade cookies, a freezer that’s packed with ravioli, art supplies. There are movies, rom-coms there they can watch, and there are massage therapists, doulas, healing justice practitioners.

The goal of the people who have assembled to care for these women, Joan Lamunyon Sanford told me—she’s the director of the New Mexico RCRC—the goal is to counteract the message that these patients have been sent in their home state, which is, “You don’t deserve to be cared for.” She says, “We take care of them. We say to them, `No, you are worthy and deserving of that care.’”

JW: Then they fly back to Texas.

AL: When they get ready to leave the state, after a day when often these patients have bonded together—they didn’t know each other at the start of this journey, but often they’ve come together in the crucible of this experience—and that’s when Reverend Erika Ferguson says to them, “Listen, this is where I’m going to say goodbye to you, because we don’t know what’s going to happen when this plane touches down in Texas.” She understands that there is a risk that she could be arrested, and she says to them, “If you see me get arrested or if you see anything happen to me, I want you to walk away as if you have never met me before.” That’s when it begins to dawn on these patients the risk that Reverend Ferguson is taking by traveling with them.

What’s amazing, right, is that in 2020, before we started to see these bans come into play in this way in the post-Dobbs era, there were about 5,800 abortions in New Mexico and about 58,000 abortions in Texas, so the need from Texas alone is enormous. Of course, when clinics in Texas were forced to close, this drove this surge of patients who were medical refugees who needed abortions, who were going to have to either travel, self-manage or stay pregnant.

A lot of clinics did follow the flow of patients to New Mexico. The Pink House, the last abortion clinic in Mississippi, which was of course the plaintiff, Jackson Women’s Health Organization, in the Dobbs case that took down Roe v. Wade, they have moved to Las Cruces, New Mexico. Amy Hagstrom Miller, who sued the state of Texas I think it’s 11 times—she is a Texas abortion provider, has been victorious at the Supreme Court before back when it had a pro-choice majority—she has opened a clinic in Albuquerque. Dr. Alan Braid, who of course wrote a Washington Post op-ed admitting that he had violated the Texas six-week bounty hunter law that was in place before Texas banned abortion outright, he has opened a clinic in New Mexico as well.

JW: Then there’s the state of New Mexico itself.

AL: Right. Michelle Lujan Grisham, the governor of New Mexico, has signed an extraordinary measure. She’s allocated $10 million in state funding for a new clinic along the border. New Mexico has really gone to great lengths not only to just defend the status quo, but to say, “We are going to make sure that we’re an abortion haven, and we are going to try to do everything we can to ramp up care and take care of people who are coming from other states.”

JW: You talked briefly about the New Mexico Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice, NMRCRC. Tell us a little more about them.

AL: They are an amazing organization. They’re an abortion fund. Many listeners might be familiar with abortion funds. These are organizations that pay for people’s abortions and pay for associated costs. Oftentimes they’ll pay for travel, for hotels, for childcare, for things that are increasingly necessary when patients need to travel for abortions. Their roots really date back to the religious tradition of helping people get abortions, which is part of the conversation about religion and abortion that often gets left out. In the years before Roe v. Wade, clergy formed the Clergy Consultation Service, and they were helping people get abortions, and often openly so. These networks were out front and at the forefront of helping people get access to safe abortions in the pre-Roe era.

In 1978, New Mexico Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice was formed by people that their director, Joan Lamunyon Sanford, called volunteer church ladies, I think very fondly. She got involved in the organization. She at one point was running it out of her den. It was a really grassroots organization, and there were times in its history where there wasn’t a ton of demand. Now in the post-Dobbs era, they’ve seen an enormous rise in demand, and their volunteers and their staff are moving mountains to bring people into the state to get the abortions they need.

JW: A few numbers that you reported in The Nation: How successful has Texas been in preventing women from getting abortions?

AL: What we know in terms of the effectiveness of these bans first of all is that any person being forced to remain pregnant against their will is a human rights tragedy. In a certain sense, it’s not the numbers that matter. It’s these individual human experiences and the very basic fact that it’s people who are already facing poverty, already facing racism and social disadvantages, who are most impacted by these bans.

What we know is that in 2020, again, there were over 58,000 abortions provided by clinicians in Texas. In 2021, of course, Texas banned abortion at around six weeks. The way that they got around Roe v. Wade still being the law of the land, of course, was with this civil enforcement mechanism that allowed everyday people to sue in order to enforce the ban. Clinics stopped providing care after about the six-week point, and in the months after that, the number of abortions recorded in Texas dropped by half.

JW: I also learned from your piece that in the six months after Dobbs, the number of abortions performed by clinicians nationwide dropped by more than 32,000. On the other hand, we know that about half of all abortions pre-Dobbs were medication abortions. Are those still being counted, especially in states like Texas where it’s officially illegal?

AL: They are not. It’s hard to fully understand the numbers, because what people familiar with the informal networks around abortion pill access have told me is that there’s more than enough medication abortion being shipped into this country and circulating in informal networks within this country to make up for the gap in abortion since the Dobbs decision. What we don’t know is how much of that medication abortion is making its way into the hands of the people who need it, because those abortions exist in a legal gray zone. They’re risky in many places, and so nobody’s recording them officially as far as I know.

Activists familiar with this network tell me that it is robust, that it is flourishing, that people are self-managing their abortions at home, in every state in the country. WE TESTIFY and INeedAnA.com, two abortion rights organizations, put out a newspaper on the Dobbs anniversary. I think it was called The Abortion Times, and the headline was “We Are Having Abortions All Across the Country. We Are Still Having Abortions.” I think that’s one of the top-line takeaways since the Dobbs decision.

I don’t want to put too much of a sugarcoating on it, because again, plenty of people are not able to get access to abortion. Those are precisely the young people, the people of color, the low-income people who are not able to travel. We need to care about every single one of those procedures that is being denied. On the other hand, I think these grassroots networks should be very proud of the work that they’ve done.

JW: In this new world of abortion, abortion seekers and abortion drugs are moving freely. The drugs are moving into the red states, the patients are going into the blue states and more clinics are moving to the blue states, but also more efforts are being made to stop people from crossing state lines to get to them. You report on what’s going on with Texas anti-abortion activists going to Clovis, New Mexico.

AL: This is a perennial figure within the anti-abortion movement and someone I’ve written about a lot, Mark Lee Dickson. He was referred to in a Huffington Post article as the traveling salesman of the anti-abortion movement years ago. He started out in Texas with ordinances called “Sanctuary City for the Unborn,” ordinances where he would try to ban abortion, and did pass these ordinances in towns across Texas. He worked with Jonathan Mitchell, the architect. Together they would go on to promote this six-week abortion ban.

No one really took notice of what they were doing in the beginning, but it turned out that the private civil enforcement mechanism they were using in these ordinances would make its way into Senate Bill 8, the Texas six-week ban, that became the law of the land and allowed Texas to ban abortion at six weeks while Roe v. Wade was still in effect.

Now Jonathan Mitchell and Mark Lee Dickson have paired up again. They’ve made a version of the ordinance that they hope is going to fly in New Mexico, a state that is going to great lengths to protect abortion access. The way that they’re doing that is they’ve crafted the ordinance so that it revives the Comstock Act. The Comstock Act is a law from 1873 named for anti-vice crusader Anthony Comstock.

JW: I’m shaking my head over this idea, but please continue.

AL: I think historians are doing exactly the same thing that you are, Jon. Anthony Comstock would go after people for pornographic drawings, for filthy material, what he considered any filth, or information about contraception. Margaret Sanger and Emma Goldman famously ran afoul of his anti-vice laws, and this law from the Victorian era also banned the mailing of abortion-related drugs, devices and paraphernalia.

What Jonathan Mitchell and Mark Lee Dickson are arguing is that this law, which hasn’t been enforced in almost a century, is in fact still in force, that it bans the mailing of all abortion drugs and devices. If the Supreme Court decides to take them at their word, this would result in a total nationwide abortion ban, because providers would not be able to operate if they can’t get abortion-related paraphernalia and devices. They can’t order surgical gloves. This could be extended to include a whole lot of different necessary items including medication abortion itself, which as you pointed out, is the most popular form of abortion nationwide.

This is their next crusade. They’re doing it in New Mexico I think quite intentionally. They’ve already gotten opposition from the State of New Mexico, which I think is what they want. They are hoping that they will get enough legal cases in the air that it entices the Supreme Court to tackle head-on the question of whether the Comstock Act and its literal reading based on the text of the law is still in force and amounts to a total nationwide abortion ban.

JW: Why do they want to do this with the Comstock Act?

AL: It’s a great question, and I think the answer is at the top, you read some statistics about how the American people feel about the idea of a nationwide abortion ban, okay? I think a lot of Republicans, especially in the wake of the 2022 midterms and the red wave that never was, are realizing that supporting the most extreme anti-abortion policies is a losing proposition for them. I think anti-abortion activists are reading the writing on the wall and understanding they’re not going to pass a nationwide abortion ban anytime soon. In fact, these state-level abortion bans that are passing are deeply unpopular, even in red states.

They’re looking at the history books and they’re thinking, “What laws are already out there? We don’t need to pass them, they don’t require the buy-in of the American people?” All it requires, as happened with the Dobbs decision, is an extremely conservative Supreme Court, and guess what, they’ve got that. I think that’s where a lot of these strategies are coming from—he idea of subverting the democratic process entirely and reviving these zombie laws from the history books, rather than trying to pass new proposals that would not gain public approval.

JW: I understand that last weekend you went to the National Right to Life Convention in Pittsburgh. Are they feeling triumphant and celebrating their historic victory at the Supreme Court?

AL: You might think they would be, Jon, a year after the Dobbs decision, right? I mean, they worked for almost half a century to overturn Roe v. Wade. What I found, in fact, is that they are not celebrating. In fact, the tone there was very somber and measured. While of course many of them, especially people in states where they have succeeded in banning abortion, were proud of that, overall, I think what they’re realizing is that they have two very serious problems on their hands. The first, which we’ve already talked about, is that their bans are deeply unpopular, and their extreme vision for anti-abortion policy, which is banning all abortions except to save the life of the pregnant person, is something that a very small minority of the population shares. The second problem that they have on their hands is that these bans are not working anywhere near as well as they had hoped they would.

I was on a panel with James Bopp. James Bopp has been a conservative activist for many years. He’s been general counsel of National Right to Life since 1978, and when he found that campaign finance rules were getting in his way with trying to curry favor with politicians, he decided to take those down along his journey to overturning Roe v. Wade. That culminated in the Citizens’ United Supreme Court decision. He was the architect of that. He’s also one of the main strategists behind the incremental chipping away, chipping away, chipping away at abortion access over time. That’s really his hallmark strategy, and it led to the overturning of Roe v. Wade and this huge victory.

He read aloud to this room, at his panel at National Right to Life, a new statistic that just came out from the Society for Family Planning, and he said he would’ve expected the number of abortions to drop by something like 300,000 after the Dobbs decision. Instead, after Dobbs, what this new survey has found is that in the nine months after Dobbs, the number of abortions dropped by about 25,000. This number is very disappointing to people like James Bopp, and when he read it aloud in this meeting room at the National Right to Life convention, you could have heard a pin drop. In fact, I heard somebody whistle. They were not pleased with that number.

These bans are not working. I think the credit for that in large part belongs to groups like the New Mexico Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice, belongs to activists like Reverend Erika Ferguson, who are moving mountains to get people access to abortions. These bans have turned out to be quite permeable, and they’ve come at great political cost.

JW: After all your travels for the last few weeks, what do you conclude about life on the abortion borderland?

AL: Well, Jon, what I’ve concluded is that the anti-abortion movement has yet to come up with a ban that can’t be circumvented by a plane trip or road trip, or by someone handing a friend five white tablets that fit into the palm of their hand. The fatal flaw in the anti-abortion strategy is that plenty of people are still doing this work despite the risks, people like Reverend Erika Ferguson, abortion funds all across the country. That is the hopeful note that I end my piece on.

JW: If people want to help, what do you suggest? For instance, the New Mexico Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice?

AL: Yes, absolutely. The New Mexico Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice is a great place to donate. You can also go to the National Network of Abortion Funds if you want to find your local abortion fund. I would also encourage people to go to The Nation’s website and read the entire amazing special issue, and we do have a list of information in there for ways that you can help.

JW: Amy Littlefield’s report on the abortion borderland is the lead piece in the new issue of The Nation Magazine. You can read it online at TheNation.com. Amy, thanks for talking with us today.

AL: Thank you so much, Jon.

[BREAK]

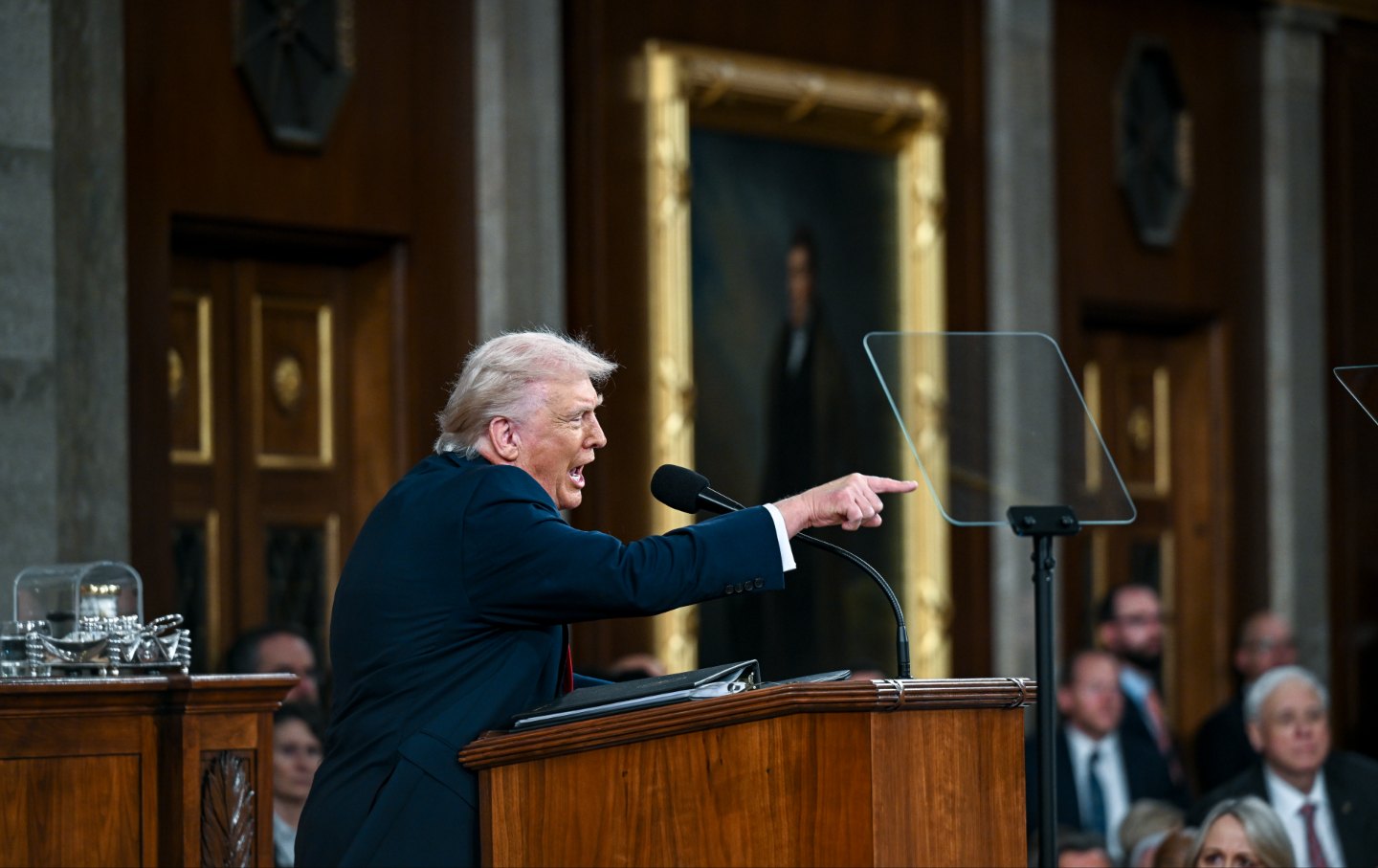

Jon Wiener: Twenty percent of likely Democratic voters tell pollsters they support Robert F. Kennedy Jr. in his primary challenge to Joe Biden. Kennedy, of course, is best known as an anti-vax conspiracy theorist. Joan Walsh has written a magnificent piece for The Nation about her history with Kennedy in his crusade. She’s national affairs correspondent for the magazine. She’s been a commentator on MSNBC and CNN. She’s written for The New York Times, The Washington Post and the LA Times, and she served as editor in chief of Salon for six years. We reached her today at home in Manhattan. Joan, welcome back.

Joan Walsh:Great to be back, Jon. Not a fun thing to rehash, but…

JW: You were there at the beginning when Kennedy first made a splash as an anti-vax figure in 2005. That’s when Salon and Rolling Stone jointly published an article under his byline headlined “Deadly Immunity.” You were the editor of Salon at that point. The article asserted a link between a purported increase in autism and the presence in vaccines of something called thimerosal, a compound use as a preservative. The fact is there has never been any scientifically valid evidence for this link. That’s why Salon ended up publishing five corrections to Kennedy’s article and finally removed it from its website in 2011. Now those events are back in the news because Kennedy has declared recently that Salon caved to pressure from government regulators and Big Pharma. And as I said, you were the editor of Salon. How does that piece, “Deadly Immunity,” published 18 years ago, look to you today now that Kennedy is talking about it again?

JW: It was the worst mistake of my career to publish that piece. I knew it had some flaws. I didn’t know how terrible they were. It was a complicated partnership with Rolling Stone where I did the line editing and they did the fact checking, and supposedly they had a great fact checking department. I don’t want to throw stones. They had stuff going on. We had stuff going on. Everybody was overworked. I didn’t have major misgivings. I just thought he was just trying to make it a conspiracy where it wasn’t necessarily, and then not acknowledge that they did take thimerosal out of childhood vaccines out of an abundance of caution, the CDC said. But that was in 2000 and rates were continuing to rise to where they were skyrocketing. And there are a lot of people who don’t like us to talk about autism as some sort of disability. Anyway, really, by 2005, you could already see, well, if this preservative really causes autism, well autism rates should be going down now that they took it out. But they did not, and they continued to skyrocket.

JW: And you worked pretty closely with Kennedy on the original piece. What was that like?

JW: Sometimes it was fun. It was all over the phone. I don’t know if I ever met him. He’s very funny. He’s got a sense of humor. I’m sure I was a little bit dazzled by the Kennedy magic, which comes across more fully in person. He has this widely discussed voice problem. I don’t think it’s hard for him anymore, but he has a very gravelly voice. We cut a 20,000-word manuscript down to like 3,500. So there was lots on the cutting room floor. He didn’t agree with all those changes. That’s fine. And then our phones started ringing and our email started blowing up with people complaining about the story, making specific requests for correction.

JW: You published a series of five corrections, but then several years later you decided to withdraw the piece entirely. What led you to take the final step?

JW: I think a really major factor, I have to say, was Seth Mnookin’s book The Panic Virus, which had a whole chapter on RFK and touched on Salon and the real mistakes—the really, I think, willful seeming distortions in the piece. You get to a point where you trust most of the spellings of names, but not much else. So I’ve felt for a while that I always like to side with transparency. And so the thing to do is append a really long correction to the top. I just thought that this piece, it had lived through so many generations of errors that it should come down. And several of us talked about it. As it turns out, David Talbot, who had stepped down as editor-in-chief, I had just taken over for him only a few months earlier, he really opposed taking it down. And he will still say that, he knows we didn’t cave to big pharma, but he thinks we caved to something.

JW: Kennedy says you caved to pressure. In your piece you say there was a lot of pressure on you. But from whom?

JW: From scientists and advocates who knew the truth, who’d been debunking this for a long time. It was still pretty early in the annals of anti-vax activism, but it wasn’t that early. And there was a cottage industry of people I would describe as kind of cranks, who were pushing these misinterpreted scientific findings and finding things that weren’t there. And so that clamor became very hard to tune out. We didn’t want to tune it out. Well, I mean, I guess I would’ve liked to if it meant the story was correct. So it was just people I respected who knew about science were like, “No, that’s a terrible piece.” I mean, people who were close to me were like, “Sorry, but that was terrible.”

JW: Farhad Manjoo, who worked with you at Salon on some of these issues, has a strong piece at The New York Times this week about what it’s like to debate Kennedy on the issues and how hard it is to debate him. Because he starts with a few true statements, some people do have bad reactions to vaccines. Big Pharma has done really terrible things. And then he starts making these wilder and more ridiculous arguments. And when you start correcting his errors and misstatements by discussing the scientific evidence, he says, “You’re nitpicking.” And then he says, “‘You’re making Republican talking points.” And then he says you’re wrong, he is not an anti-vaxxer. He’s merely a vaccine safety advocate. He says, all he wants to do is make sure that vaccines are subject to the same kind of safety testing that other drugs are subject to. And if you tell him, in fact, vaccines are subject to greater scrutiny than drugs by the FDA, he’ll tell you, don’t believe the FDA, they’ve been captured by Big Pharma. So you point to other scientific evidence and he says, well, there’s arcane disputes about those numbers. And then he goes on to something new like WiFi radiation may also cause autism. It’s confusing to listen to these debates. And people say, well, he’s made a few good points. Big Pharma is not to be believed in every case. And maybe he’s right about some of this other stuff too. After all, he’s a Kennedy.

JW: Well, he’s not right. Brandy Zadrozny, writing for NBC News, wrote a really terrific piece that I linked to in my piece, where she really teased out the implications of his beliefs. If he was President Kennedy, which is a weird mental exercise because we all know we had a President Kennedy, and we lost him, but he says he would stop administering childhood vaccines until they can be studied more, meaning that children would suffer and perhaps die unnecessarily while he tests vaccines that have been studied, some of them, for my whole life. I mean, he would gut the CDC, the FDA, the NIH, they’re all captured by big pharma. And he would either restaff them or have newly staffed agencies where he would put in his people. And she asked who those were, and he said, “Well, I’m not going to get into that till I vet them.”

It sounds like a nightmare. I mean, the COVID vaccine saved so many lives in this last tragedy that we all lived through. We know so many people who survived and also didn’t get really bad cases of it, didn’t get long COVID. I think the thing that really pushed me over. I was thinking about doing it, but two things:He was on with Joe Rogan for three hours. Believe me, I didn’t listen to the whole thing. But he repeated with Joe Rogan, this idea that I had caved to big pharma. That was bad enough. But then Dr. Peter Hotez, who’s a famous public health vaccine expert, took him to task and said that it was a parody of a conversation and he should be ashamed.

And so then Joe Rogan starts trolling. Dr. Hotez, “Come on my show and debate Bobby Kennedy, and I’ll give your favorite charity $100,000. And he is like, “No, absolutely not.” And then Elon Musk and a bunch of his tech bro morons are doing the same thing. And on Father’s Day, he was coming home and he found two QAnon people on his doorstep demanding that he debate RFK Jr. They did not mean him harm, but I would not like to face that on my doorstep. So this poison of conspiracy theorizing, which again, takes off from some truth, that there has been regulatory capture of many of our health agencies as well as the agencies that regulate banks, the people who are supposed to be performing the public good and scrutinizing these situations, or they become lobbyists or they were lobbyists already. All that’s true, but the answer isn’t spouting a bunch of easily debunked lies and eroding people’s trust even more.

JW: And along the way, perhaps persuading enough Democrats not to vote for Joe Biden, to make Donald Trump president again.

JW: Yeah, he can’t win the nomination. He can just cause a lot of mischief. But he won’t necessarily commit to voting for Biden if Biden defeats him in a primary. So he’s playing that game too. So it’s very dangerous and people have to treat him like the charlatan he is. With obvious family history, tragedies, illnesses, he hasn’t had it easy, but he’s doing damage.

JW: One last thing: I wanted to ask a little more about your remarkable piece at The Nation. It’s been number one at the website, for good reason. You could have just attacked Kennedy for his recent lies about the piece that you edited. Or you could have said, “We all make mistakes. I’ve made some; who hasn’t?” But instead, you wrote that this was the worst mistake of your career. It takes a lot of courage to do that. Not very many people do it. How did you decide to do it that way?

JW: I don’t know. That made the most sense for me because I could tell the story of the forces that combined to get me to do something like that. I really think that I should have been fired. In today’s world, I might be fired for something that stupid. With social media, if the really smart activists and the smart scientists started coming after Salon, I mean 2005, we had blogs. So I felt that very strongly. It’s a real blight on my otherwise sterling career.

JW: Yes.

JW: And I felt like I had to come clean about the forces of—Jann Wenner was on Salon’s board, and so was David Talbot. I was just starting. They both really believed in this piece and they thought it was quite a coup, that we’d gotten Bobby to do it for both of us. And so it was something with some prestige that these powerful guys wanted me to do. Now, I would stand up to them multiple times later, but at that point, I think I just bought into the magic, the myth, the Rolling Stone fact checking. It’ll all work out. And it didn’t. It didn’t work out at all.

JW: Joan Walsh. You can read her report at TheNation.com. It’s called “Just Another RFK Jr. Lie. I Know Because it’s About Me.” Joan, thank you for this terrific piece, and thanks for talking with us today.

JW: Thanks, Jon. Always a pleasure.