The ongoing struggle for racial justice. The future for immigrant families. The health and well-being of all Americans. The very fate of our fragile planet. The United States faces a crossroads in 2020. Seeking out the stories flying under the national radar, The Nation and Magnum Foundation are partnering on What’s At Stake, a series of photo essays from across the country through the lenses of independent imagemakers. Follow the whole series here. This installment was produced with support from the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.

Even before the coronavirus, America’s health care system was in crisis. Skyrocketing costs for patients, an accelerating work pace for nurses and other health care workers, and a tangle of private and public insurance bureaucracy throw up barriers to care for millions of Americans. But this doleful situation isn’t for lack of doctors, or lack of facilities, not really. At heart, what is strangling America’s health care system is that we still don’t count health care among the human rights to which we’re all entitled—we still largely view the health of our fellow citizens as another potential source of profit.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the many rural areas where hospitals are being shuttered at an alarming rate. A local hospital—easily accessible, with short wait times—can be a boon to residents seeking care, but it’s not a recipe for moneymaking. Appalachia is an epicenter for this health care emergency: According to the University of North Carolina’s Sheps Center for Health Services Research, 23 hospitals have closed in the region in the past decade. There is no doubt that 2020 is a record-breaking year, with eight hospitals already shutting their doors in Appalachia. When the pandemic struck, and hospitals were forced to largely suspend outpatient care and elective procedures, rural facilities already teetering on the edge of bankruptcy were pushed over the edge.

Right now, coronavirus infections in rural communities are skyrocketing. Hospitals in eastern Tennessee, where I live, are reaching capacity. Yet we have the second highest rate of hospital closures in the country. Studies have found that states that didn’t expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act—states like Tennessee, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and the Carolinas—have seen the most hospital closures. A number of factors also conspire to make the coronavirus particularly dangerous in Appalachia: With a disproportionately older population, and with high rates of heart disease, obesity, and diabetes, the region has a large proportion of people who are at risk of hospitalization for virus complications.

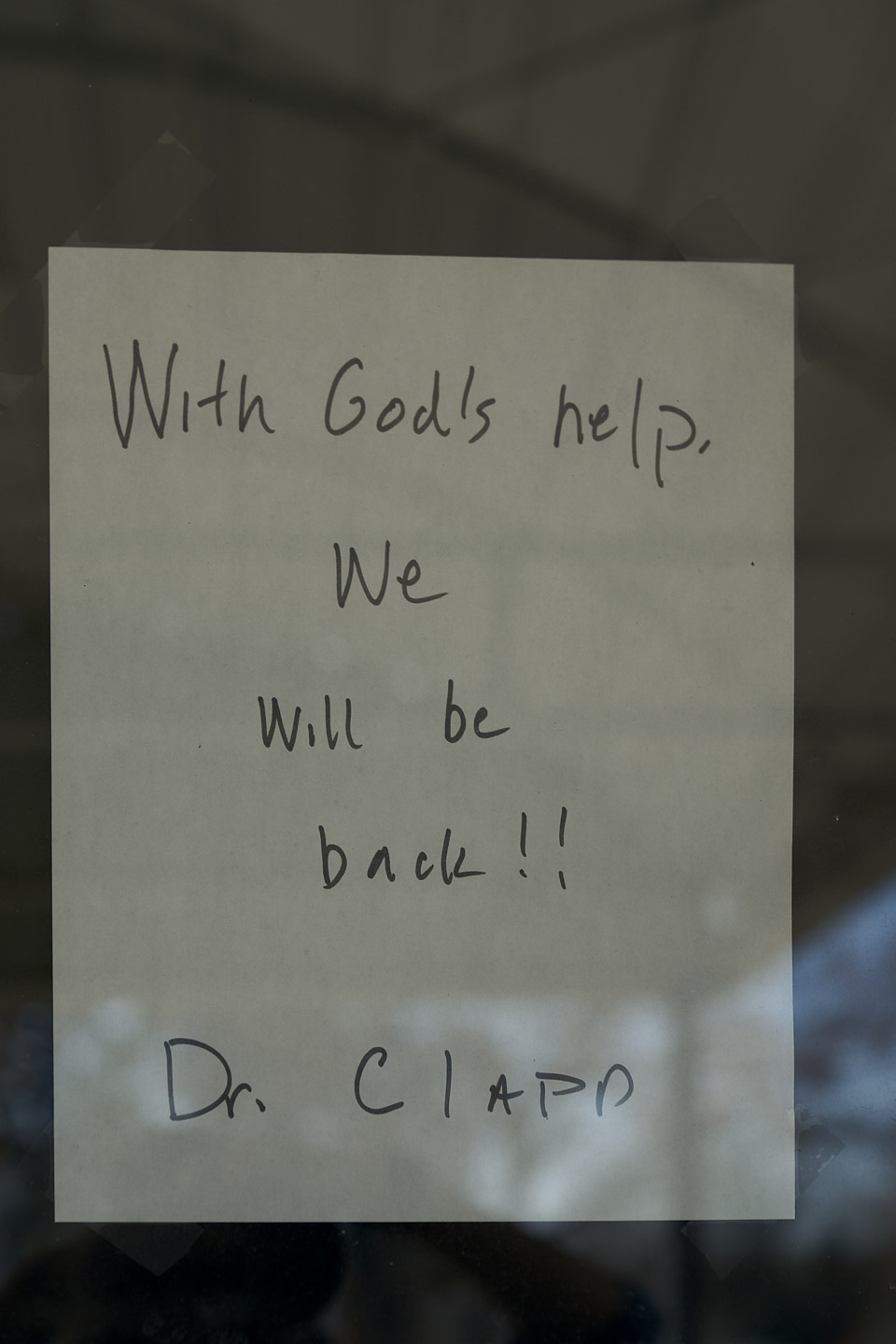

For a couple weeks this fall, I drove across the region, to the small towns that have suffered hospital closures, making my way to the facilities that used to provide health care and jobs in areas desperately in need of both. These photos capture some of the many shuttered health care facilities across Appalachia.

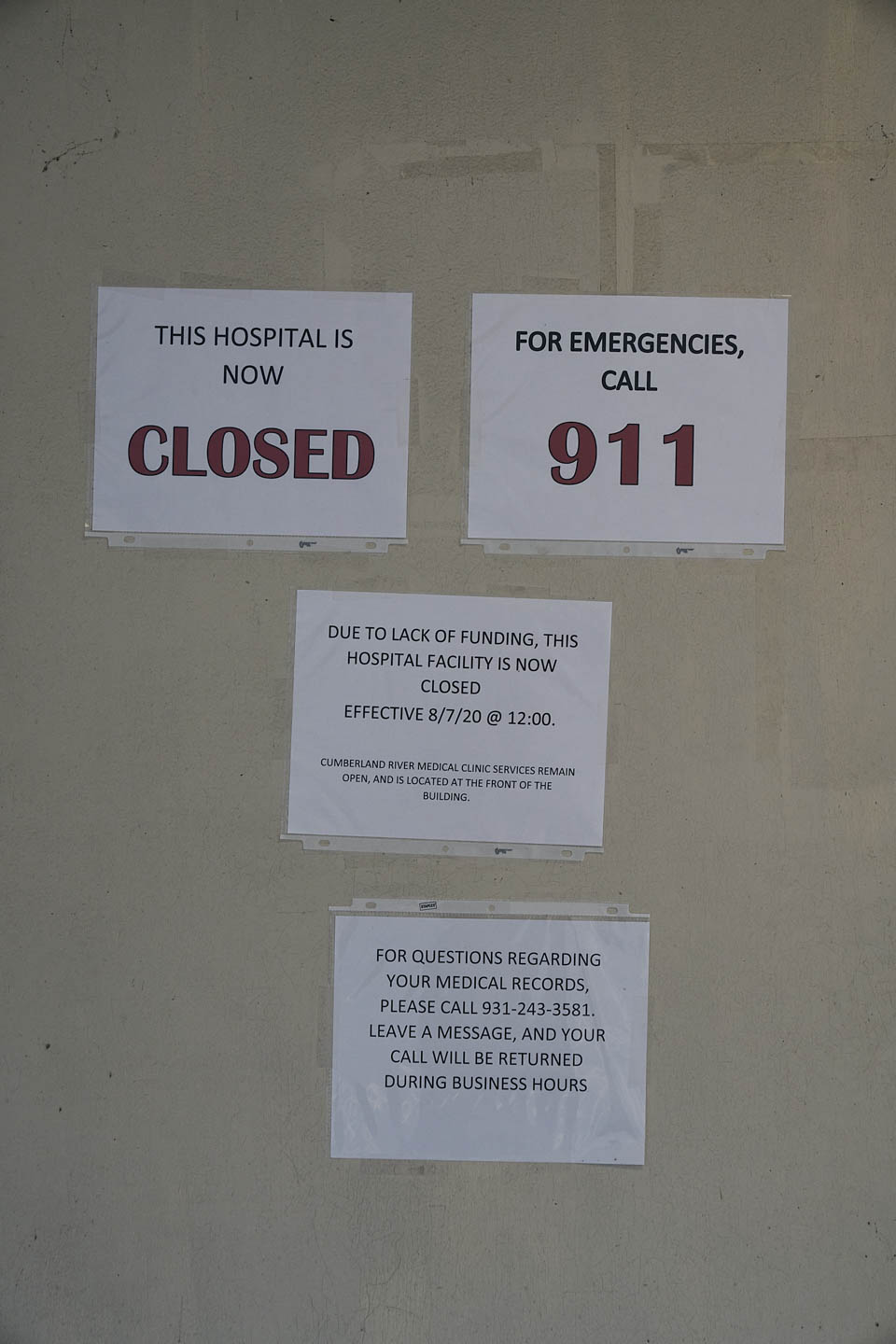

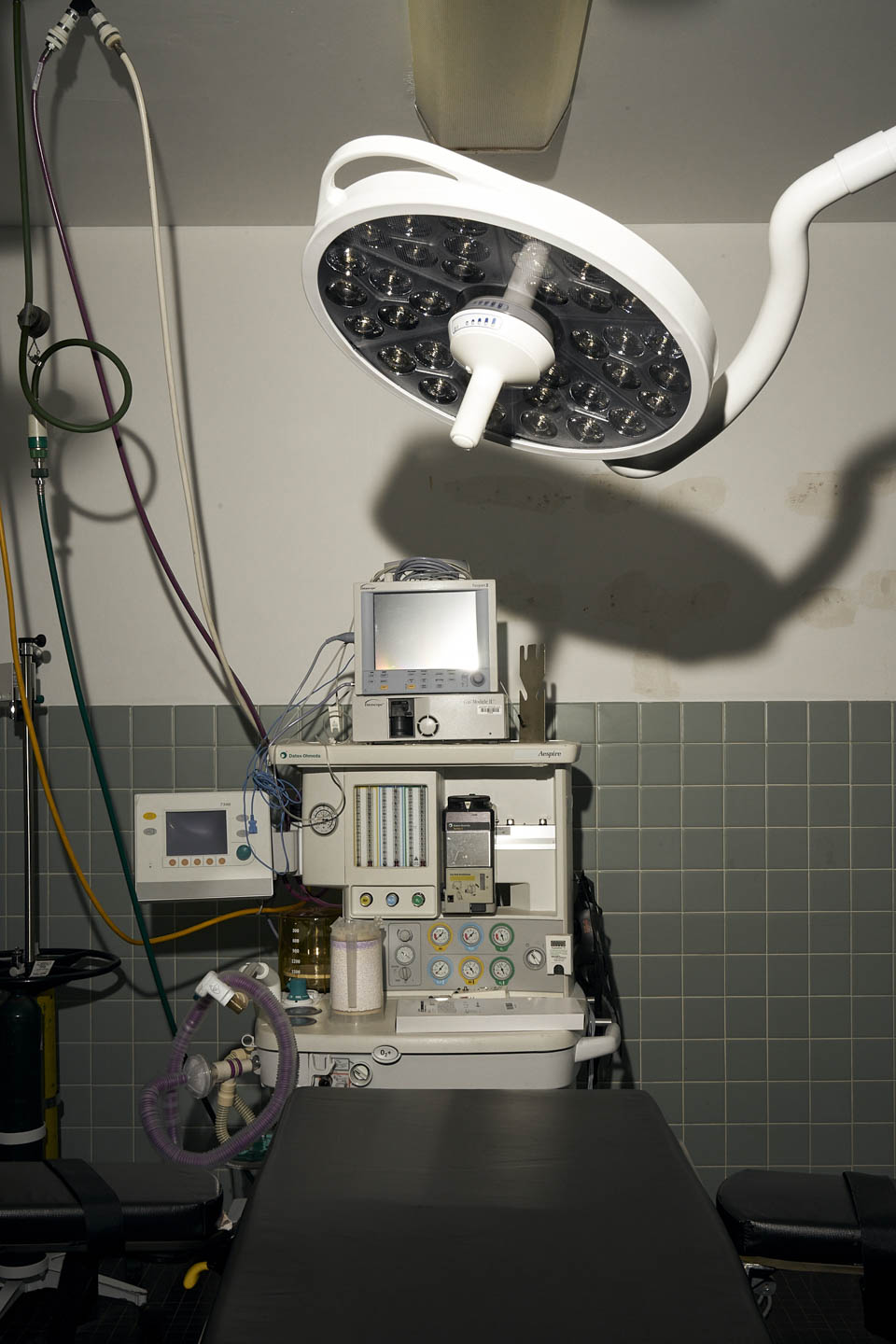

Many rural hospitals didn’t receive relief from the first coronavirus economic relief package, but they were included in a $10 billion rural Covid-19 relief fund that offered a temporary Band-Aid to many struggling rural hospitals and health clinics. The Cumberland River Hospital in Clay County, Tenn., is fully functional and ready to receive patients, but is currently closed because it did not receive any support through the CARES act, and hasn’t yet received support from subsequent relief packages. As the pandemic escalates and the flu season begins, Clay County has no available medical care between the hours of 5 pm and 8 am.

In nearby Jamestown, Tenn., the Jamestown Regional Medical Center closed in 2019. Since its closure, people have still rushed to the hospital in dire need of care, only to find its doors locked—they end up in the parking lot of Clarke’s Acute Medical Clinic across the street, but the urgent care facility does not have the kind of equipment needed to restart someone’s heart, and patients have died before they could be taken the 30 miles to the nearest hospital.

Mingo County, W.Va., was the site of the 1920 Matewan Massacre, a deadly battle in America’s labor history that pitted the United Mine Workers of America against a coal company’s guns for hire. Coal mining was vital to West Virginia’s and Virginia’s economies, and the steep and steady decline in the number of mining jobs has been devastating. Hospitals like Williamson Memorial Hospital—the only one in Mingo County—were something of an economic lifeline: They are usually the largest employers in these economically depressed areas, and offer the highest-paying jobs. New industries are also less likely to come to areas without a hospital. Williamson Memorial shut down this year at the beginning of the coronavirus outbreak.

A few hours away, a merger of two hospital systems in parts of northeast Tennessee, Virginia, North Carolina, and Kentucky drastically altered the shape of care in 29 counties. Federal officials had objected to the merger, on the grounds that it was creating a medical monopoly. But the consolidation went ahead anyway, and Ballad Health, the name of the system that resulted from the merger, now is effectively the only health care provider for a region the size of New Jersey. In the 2018 merger agreement, Ballad is not allowed to close any hospitals for five years, and it is reopening a hospital in Lee County, Va., that was closed in 2013. For Ballad, these rural hospitals are considered referral hospitals, bringing rural populations into Ballad’s urban facilities.

As rural populations shrink and hospitals continue to consolidate, these trends will only accelerate. Unless there are drastic changes to how we apportion health care in this country, the future of rural care will be either no care, or no choice.