THE NATION CLASSROOM

American History as It Happened

RACE RELATIONS and CIVIL RIGHTS

MODULE THREE: 1900-1918

DBQ: More than four decades after the Civil War ended, African-Americans encountered massive obstacles to their advancement. Using the documents below and your knowledge of outside events, describe at least three of those obstacles and assess how serious a threat they were to African-American success.

|

DOCUMENT ONE Source: “The Souls of Black Folk: Essays and Sketches by W.E. Burghardt Du Bois”, unsigned book review, The Nation, June 3, 1903 Mr. Du Bois has written a profoundly interesting and affecting book, remarkable as a piece of literature apart from its inner significance. …[T]he most concrete chapter … is the third, “Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others.” Mr. Washington’s ascendancy is designated as “the most striking thing in the history of the American negro since 1876.” Entertained with unlimited energy, enthusiasm, and faith, his programme [sic] “startled and won the applause of the South, interested the admiration of the North, and, after a confused murmur of protest, it silenced if it did not convert the negroes themselves.” The merits of that programme are detailed with warm appreciation… The criticism is that Mr. Washington asks the negro to surrender, at least for the present, political power, insistence on civil rights, the higher education. Advocated for years, triumphant for ten, this policy has coincided with the disfranchisement of the negro, his relegation to a civil status of distinct inferiority, the impoverishment of institutions devoted to the negro’s higher education. That here is not merely coincidence, but effect, is Mr. DuBois’s contention. Also, that Mr. Washington’s desired ends cannot be reached without important additions to his means. The negro may not hope to be a successful business man and property owner without political rights, to be thrifty and self-respecting, while consenting to civic inferiority, to secure good common-school and industrial training without institutions of higher learning. “Tuskegee itself could not remain open a day were it not for teachers trained, in negro colleges, or trained by their graduates.” It is not so clear to us as it is to Mr. Du Bois that Mr. Washington has made the base concessions here ascribed to him… But this third chapter as a whole, and the expansion of its prominent details in the succeeding chapters, deserve the carefullest consideration. Their large intelligence and their lofty temper demand for them an appreciation as generous as the spirit in which they are conceived. |

|

DOCUMENT TWO Source: “The Negro Problem in Foreign Eyes,” unsigned article, The Nation, February 21, February 18, 1909 [T]here must be many thousands of people whose minds have turned to the extraordinary progress of the American negro since Lincoln struck the shackles from his limbs. Illiteracy cut from the 95 per cent of 1865 to 87 in 1870, and in the three decades between 1870 and 1900 to something over 40; the ownership of vast tracts of land, their invasion of the industries and the professions—these things would strike with amazement those who gave their lives for the liberty of the slave could they but see the results of that great sacrifice. |

|

DOCUMENT THREE Source: “Booker T. Washington’s Greatest Service,” unsigned article, The Nation, December 9, 1909 The remarkable success of Booker T. Washington’s latest speaking-tour of the South emphasizes again his usefulness to the whole country. In this role as an interpreter of one race to another, pleading for harmony, mutual respect, and justice, he is performing a patriotic service which it would be hard to overestimate. One of the foremost white educators now at work in the South exclaimed on hearing of the details of Mr. Washington’s recent trip through Tennessee: “Now I believe there is going to be a revolution in the South in favor of the negro.” Of the fifty thousand persons who, it is estimated, attended his meetings, nearly one-half were white; and in every case he was received with an enthusiasm which would have turned the head of any less balanced and sagacious leader. |

|

DOCUMENT FOUR Source: “The Negro and the Unions,” unsigned article (written by Oswald Garrison Villard), The Nation, December 1, 1910 …Labor unions that draw the color-line or refuse admission to Italians or other nationalities give the lie to the union assertion that theirs is a movement for true economic equality and genuine democracy. But if Mr. [Samuel] Gompers [president of the American Federation of Labor] denies that he attacked the negro race and wished to exclude them from the unions, there is nothing in his utterances at St. Louis or elsewhere which we have seen that indicates an earnest desire to enroll many negroes among his supporters to give them a real welcome. He dwells on the difficulties of handling the colored workers; he does not seem to declare that these are precisely the difficulties the union movement likes to grapple with and meet. As a matter of fact, his attitude reflects, in the main, that of unions throughout the country. Few welcome the negro with open arms. |

|

DOCUMENT FIVE Source: “The Week” unsigned article [about Baltimore real estate segregation], The Nation, October 2, 1913 TO THE EDITOR OF THE NATION: |

|

DOCUMENT SIX Source: “The Casuistry of Lynch Law” by Herbert L. Stewart, The Nation, August 24, 1916 …In the lynching districts the habit is maintained far less because any special negro tendency calls for it than because on general grounds the white man there thinks it indispensable if the blacks are to be kept in their place. It is an instrument of racial terrorism, to be displayed periodically with cause or without cause, just to show who is master. Policy of this sort is soon reinforced by the easily awakened bloodlust of a mob; to-day a lynching seems to be demanded from time to time in Georgia much as the Roman proletariat called for panem et circenses [bread and circuses]; Americans elsewhere have to blush with shame, to think that there are men holding American citizenship whose nervous systems need the occasional “thrill” of a fellow-creature’s agony. We are sometimes impatiently told that this matter is the business of the Southern States alone. It is nothing of the kind. As the Nation has repeatedly insisted, it concerns the honor of America as a whole. …To remove this blot upon American life we must keep the genuine facts in such high relief before the eye of those who are not wholly stupid that average persons will be ashamed even to “admit that the lynchers have a case.” |

|

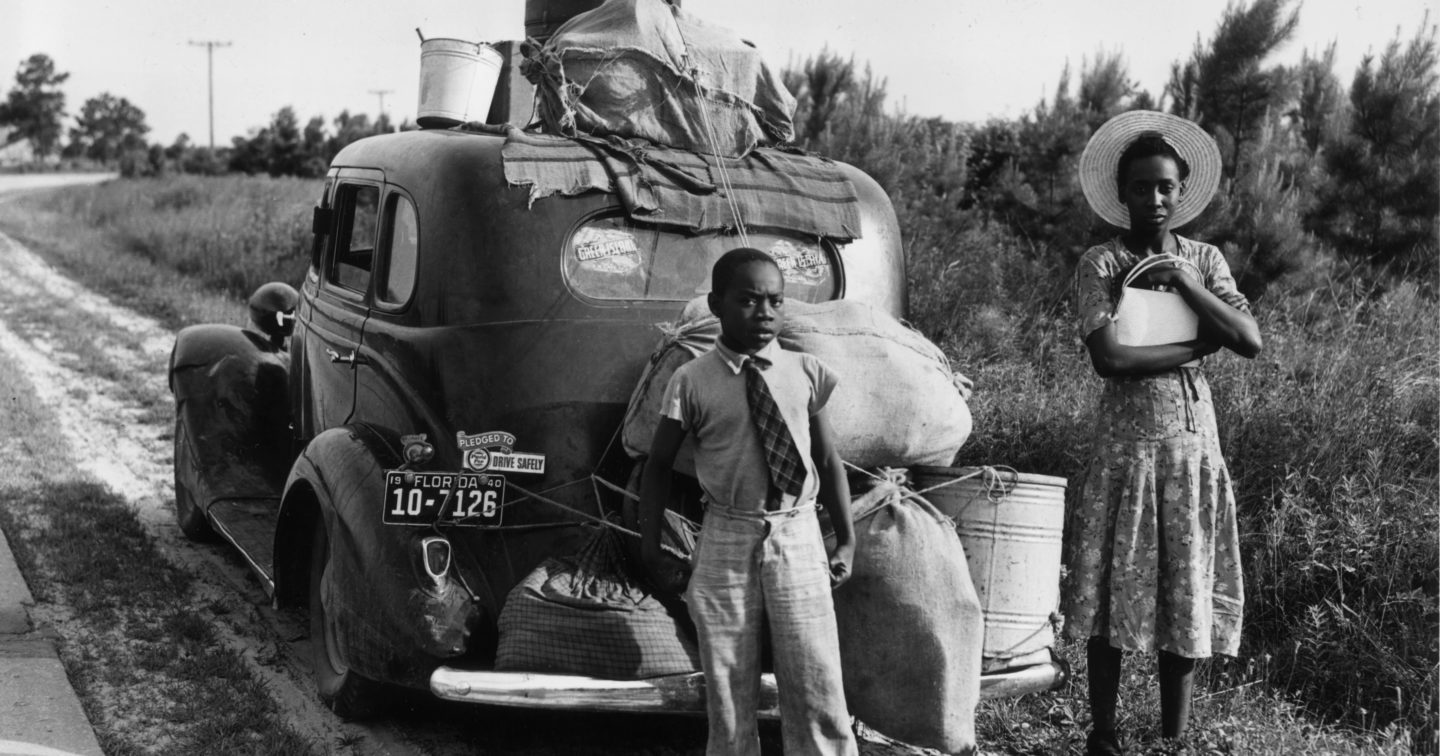

DOCUMENT SEVEN Source: “The Week” unsigned articles [riots in East St. Louis], The Nation, July 12, 1917 [Former President] Theodore Roosevelt’s sense of justice, and his fundamental belief in an ordered democracy, never shone out more usefully than in his set-to with Mr. [AFL Union President Samuel] Gompers … on Friday. His denunciatory mention of the shocking murderous riots in East St. Louis expressed only what every decent American feels. And the attempted palliation of the horror and shame by Gompers, with his hollow apologies for labor unions resisting the “tyranny” of competing workmen who had been “lured” to East St. Louis, raised a wrath in Mr. Roosevelt which was wholly righteous. His bold stand and his burning words will be noted throughout the entire land, and will help to bring about a better public sentiment. Already the citizens of East St. Louis are putting on sackcloth and ashes and are pledging themselves—though a trifle late—to give ample protection to every laborer, black or white. All thanks to Col. Roosevelt, say we, for having borne his testimony, like a brave man and a good citizen, against mob murder. … The South has opposed the migration of negroes by resort to legal restraints, and East St. Louis is taking revenge upon them by violence. Both actions are wrong. Like any other man in this country, the negro should be free to live and work where he chooses. If, in the end, he should conclude that he belongs in “the spacious, agricultural South” and not in the “crowded industrial section,” well and good, but it must be his decision and not one made for him and enforced upon him in the interest of the Southern employer and the Northern white laborer. |