The Case For Abolishing Harvard

On this episode of The Time of Monsters, Matt Bruenig discusses how elite private schools support plutocracy.

Here's where to find podcasts from The Nation. Political talk without the boring parts, featuring the writers, activists and artists who shape the news, from a progressive perspective.

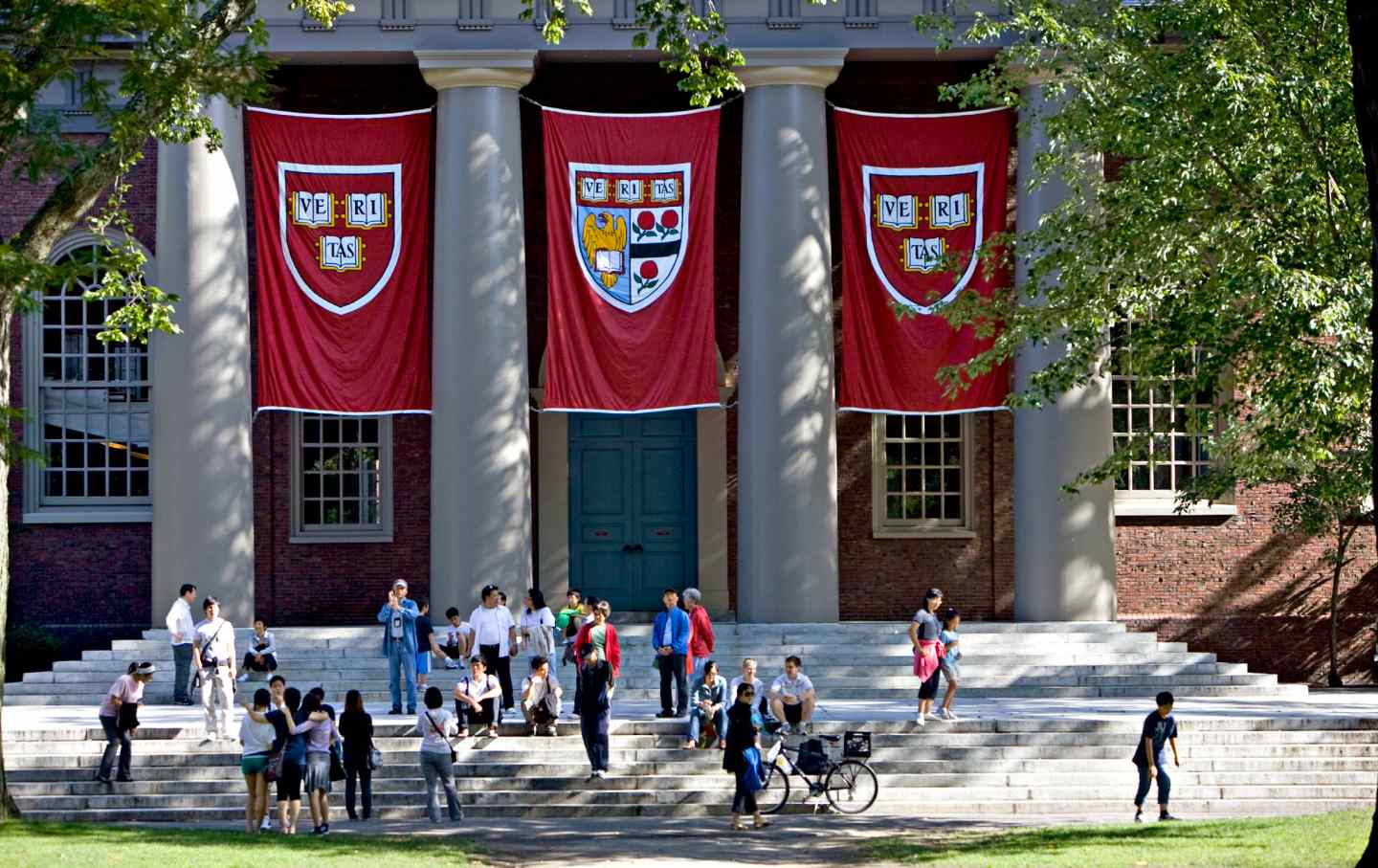

It’s no secret that the rich have an outsized role in Ivy League colleges, both as students and alumni. But a new study, by a group of Harvard-based economists, documents in detail just how much elite private education in the Untied States favor the ultra-wealthy. As the New York Times reports, “At Ivy League schools, one in six students has parents in the top 1 percent.” The rich enjoy disproportionate access to these schools due to a mixture of legacy admission, sports admissions for specialized sport programs (like fencing), and weight given to personal essays as well as letters of recommendation.

In a very real sense, elite private universities are a major pillar of plutocracy, allowing a narrow caste to hold on to social and political dominance that goes hand in hand with their economic wealth.

Matt Bruenig of the People’s Policy Project has written an excellent summary of the report. For this episode of The Time of Monsters, I talked with Matt about the problem of inequality in higher education. We take up possible reform policies and also the possibility that these institutions might be inherently harmful to democracy. This leads to a discussion of possible measures to nationalize elite private schools and absorb them into a proper and robust public education system.

Advertising Inquiries: https://redcircle.com/brands

Privacy & Opt-Out: https://redcircle.com/privacy

It’s no secret that the rich have an outsize role in Ivy League colleges, both as students and alumni. But a new study by a group of Harvard-based economists documents in detail just how

much elite private education in the Untied States favor the ultra-wealthy. As The New York Times reports, “At Ivy League schools, one in six students has parents in the top 1 percent.” The rich enjoy disproportionate access to these schools due to a mixture of legacy admission, sports admissions for specialized sport programs (like fencing), and weight given to personal essays as well as letters of recommendation.

In a very real sense, elite private universities are a major pillar of plutocracy, allowing a narrow caste to hold on to social and political dominance that goes hand in hand with their economic wealth.

Matt Bruenig of the People’s Policy Project has written an excellent summary of the report. For this episode of The Time of Monsters, I talked with Matt about the problem of inequality in higher education. We take up possible reform policies and also the possibility that these institutions might be inherently harmful to democracy. This leads to a discussion of possible measures to nationalize elite private schools and absorb them into a proper and robust public education system.

Here's where to find podcasts from The Nation. Political talk without the boring parts, featuring the writers, activists and artists who shape the news, from a progressive perspective.

Matthew Yglesias, a very influential journalist and proprietor of the Slow Boring substack, has emerged as a divisive figure within the Democratic party. To admirers, he’s a compelling advocate of popularism, the view the Democratic party needing to moderate its message to win over undecided voters. To critics, he’s a glib attention seeker who has achieved prominence by coming up with clever ways to justify the status quo.

For this episode of the podcast, I talked to David Klion, frequent guest of the show and Nation contributor, about Yglesias, the centrist view of the 2024 election, the role of progressives and leftists in the Democratic party coalition, and the class formation of technocratic pundits, among other connected matters.

Advertising Inquiries: https://redcircle.com/brands

Privacy & Opt-Out: https://redcircle.com/privacy

This transcripts was automatically generated and may contain errors.

[00:00:00] Jeet Heer: The old world is dying. The new world struggles to be born. Now is the time of monsters. With those words from Gramsci, I welcome you once again to the Time of Monsters Podcast sponsored by the Nation Magazine. So this week there’s been a lot of chatter about Harvard partially in the Nation magazine itself, where Michael Massing had an excellent report on the many.

[00:00:27] Quite connections between the late pedophile Jeffrey Epstein and the University. He was a major donor and he had all sorts of relationships with the university that continued long after he was convicted of quite serious crimes. And The nature of these connections which go up to like the highest level of the university, including the former president, Larry Summers have yet to be fully answered.

[00:00:48] But there’s other reasons why Harvard’s been in the news. One is the sort of Supreme Court affirmative action ruling which is raising all sorts of questions about, you know, the nature of elite private universities and whether they can be made to reflect the Diversity of American society and whether they’re have e equitable and fair admissions.

[00:01:08] And the, maybe the final reason and is a very well timed report that has just come in from Harvard from scholars at Harvard itself which look at. The effect. And to talk about that, I wanna bring on board Matt Brune who is well-known sort of policy analyst at the people’s policy project.

[00:01:28] And I think he did an excellent post that kind of sums up the research and draws us some of the sort of political implications that we can have about it. So first of all, Matt thank you for being on. Thanks for having me. And so, so let’s just start by just saying like what does this new report say about the nature of admissions to Harvard and how equal they are?

[00:01:50] Matt Bruenig: Yeah, so this, this team has been working on this question and related questions for many years and I’ve been following all of it. So it’s, it’s, there’s a, it’s a logical outgrowth of what they’ve done before. So I think like the best way to start to understand where they are in this study is to go back to 2017 when they had a similar study where they were just seeing what colleges.

[00:02:12] Where, where colleges got their admissions classes from based on income. So basically what percent of Harvard’s incoming class is from the 1%, what percent of the University of Texas incoming class is from the 1%. And they do that up and down the income ladder. And in 2017, their studies showed, you know, not surprisingly, that the top 1% was very overrepresented at top universities.

[00:02:37] So to give one number at Harvard. 15% of their incoming class comes from the top 1%. Obviously that’s 15 times what it sort of ought to be. You know, if it was, everything was socioeconomically balanced. But you know, when you put out a study like that, one response is just to say that, okay, sure, yeah, the rich are 15 times overrepresented, but rich people also accumulate more educational credentials.

[00:03:02] It could just be that they are more qualified, right? They, they. They have, you know, testing and they go to good schools and they have stable homes and nutrition, and their parents are typically well-educated and so on and so forth, right? So if we’re gonna try to figure out is the overrepresentation of rich kids unfair in the sense that it’s.

[00:03:23] Exceeds their educational credentials, then we need to do something more sophisticated. So that’s how we get the study that came out earlier this week. They focused on the eight Ivy League schools and Duke, m i t, Stanford, and the University of Chicago. They call these 12 schools, the Ivy plus schools, and they get.

[00:03:44] Admissions data from all 12 of them. Like this is really hard stuff to get super private, but all the data from these schools and then they also match that data with tax records, which are also very hard to get. And they put it all together and they’re able now to say, okay. Did rich people is rich people’s overrepresentation, you know, a function of them just being more qualified, or is it actually something else going on?

[00:04:09] And so the main way they accomplish this is by controlling for test scores. So they compare kids who have the same test scores, the poorest kids and the richest kids, but their test scores are all equalized and controlled for. And when they do that, they find that the richest kids are 2.2, perc 2.2 times more likely.

[00:04:29] Then the population as a whole to get into these Ivy Plus schools, despite having equal educational credentials. So they, you know, their chances more than double.

[00:04:37] Jeet Heer: So so it’s not just that the rich do better, like in preschools in before entering even college. They have some sort of advantage and I believe that the the study was further able to refine that finding and like basically give a, you know, rough breakdown as to what the sources of advantage are in terms of, you know, there’s a sort of infamous legacy admissions.

[00:05:00] There’s like athletics and then there’s also the sort of a advantage that comes from student essays and sort of personalized recommendations. So, so what, what’s the sort of lay of the land there?

[00:05:11] Matt Bruenig: They focus on five different factors. So you have application rates, you know, rich kids apply at higher rates, you have matriculation rates.

[00:05:20] So after you’re admitted, rich people are more likely to accept and go into the schools. I. And so those are in a sense, not related to admissions decisions, right? They’re related to decisions to apply and then decisions to matriculate. So those can I

[00:05:35] Jeet Heer: just make, make a comment on that though, because I think that there’s a tendency to sort of, you know, set these things aside because, but it’s a former pre distribution, right?

[00:05:43] Like, there’s reasons why they apply more and there’s reasons why they’re more likely to accept. You know, we, we, we can for our purposes maybe set them aside, but it’s worth thinking about. There’s already a lot of inequality baked in right there, and I would say there’s a lot of inequality already baked in in terms of test scores, but, but yeah.

[00:06:00] Yeah. Let’s continue.

[00:06:01] Matt Bruenig: No, absolutely no, I think that’s a good point. I mean, it’s similar to points people will make about the gender wage gap or something like that. Where people feel like they can go in the economy or in college. Admissions also will depend on their understanding of inequality and what’s available to them and their information and so on.

[00:06:18] So definitely class is screening for those things. But it’s not like them immediately with the form in front of ’em, just being like denied, you know? So yeah, when we put those aside, then you have the three kind of admissions criteria. Once the things get into the black box and the admission officers are looking at them, and there you have legacy preferences.

[00:06:38] Which account for 46% of the surplus rich attendees, right? So that’s the amount above what you would expect just based on test scores. 46% of that comes from legacy preferences. 20% of that comes from non-academic credentials, which includes things like teacher recommendations, extracurricular.

[00:06:56] Activities, things of that sort. And then the remaining 24% comes from athletic preferences. These schools have you know, athletic sports that they emphasize that only rich people do like fencing and stuff like that. And so athletic preferences is almost like the wrong name for it because they’re using that as well to target rich people, you know.

[00:07:19] Jeet Heer: Yeah, I don’t think any of these things are like a, an accident, right? Like it’s not an accident that lead private university that has historically been part of the economic upper class would have athletics programs in, as you mentioned, fencing rugby, rowing, you know, all sports that that class specializes in.

[00:07:39] So this is all I. Maybe the point to underscore here is this is all intentional, right? Like this is not like, oh yeah, suddenly somehow we accidentally created this system. Right? Like, that’s not

[00:07:49] Matt Bruenig: what’s happening here. It’s, it’s super intentional and I mean, one of the easiest ways to drive that home is just to recognize that these schools, I.

[00:07:57] Have vastly more qualified applicants than they admit each year. Right. As on the, on the scale of 50 times as many people who they could admit who are just, you know, high scores, like totally, you know would be able to get in and, and flourish and, and whatever. No, no question about that. They wouldn’t even deny that either.

[00:08:18] But they choose among that group. And when they choose among that group, they continue to wind up with this distribution. They could basically create any distribution they wanted because their applicant pool is so large and the number of qualified people is so large. And because their class sizes are so small they, they could do really whatever they wanted.

[00:08:36] And the fact that they’re choosing to do this is not a mistake.

[00:08:40] Jeet Heer: Yeah, no, it’s not a mistake. And I just to hit that point a a little bit more it’s not a mistake because what is the actual model for these universities? Like they actually want, like already very rich students because that’s tied up with the sort of prestige and the opportunities.

[00:08:59] That they offer, right? Like it is, this is the place where, you know, the future members of the elite will me meet other future members. And some of those could be people from the middle class or even from the poor, but you want a certain number of wealthy people yeah. In there as part of the mix.

[00:09:14] And it’s also that these are the people who are gonna be. Donating to you in terms of alumni funding and you know, like the, the common joke that something like Harvard is really like an endowment fund that runs a school, right? And so, so if, if your goal is to have that endowment fund be as massively huge as possible, like they’re doing the right thing, they’re, they’re, they’re doing actually what they want.

[00:09:38] And they’re like, the system is working. The way

[00:09:42] Matt Bruenig: it should be. Yeah, absolutely. Yeah. Yeah. I would, I would say, you know, the schools to be charitable to them on some level is they have a, a mixture of goals. And these goals are in some ways in conflict with one another. You know, on the one hand they wanna be elite research institutions and they go out and they try to get the best faculty and researchers possible on the other end.

[00:10:02] On the, another goal is to be, you know, elite educational institutions that really, you know, educate up smart kids and all the rest of it. And then you have the third goal, which is this status mongering, prestige mongering, and of course just bringing just raw dollars into the school and into the endowment.

[00:10:20] And what that requires is for them to have a sort of secondary way in for the nation’s elite families. And that’s part of the game. And that’s also kind of part of what even the non-elite. Are interested in when coming to the school is they wanna rub shoulders with those families. So these things don’t really all fit together very neatly.

[00:10:40] And, and you know, it’s to the extent that people really, in the general public, we kind of focus on their educational mission. This is obviously a detraction

[00:10:50] Jeet Heer: from that. Yeah, no, that, that, that, that’s right. And maybe, I think one way to I to look at it is that, you know part of those goals are already done by other institutions, right?

[00:11:02] Like, you already have like very good state schools that like attract. The best researchers in the world and also do a pretty good job of, you know, educating their students but they don’t have that added advantage of being the places where, you know, you’re most likely to end up on the Supreme Court or you’re most likely to work for big law firm.

[00:11:22] Right. The, the, the salient or added advantage, I mean, what’s the difference between U C L A and Harvard? Right. Like, like what? Yeah, what is the, what is the what, what’s the economic term? Like, what’s the big selling point? What’s the, the, the, the, what’s the marginal benefit? What’s a marginal benefit that Harvard provides?

[00:11:40] Right.

[00:11:41] Matt Bruenig: Yeah. I mean, on the education side, nothing, right? Yeah. There’s no, there’s not gonna be any difference really in like the top a hundred universities in the US there’s 4,000 undergraduate institutions in the us. So I mean, the top a hundred, you’re, you’re already pretty elite including most flagship state universities and, and all the rest of it.

[00:11:59] And I mean, there’s, there’s just only so much you can do. You’re dealing with, you know, teaching English. Classes, English literature to 20 year olds. Like, what, what really can the stratification of that look like? You know, at the top, like this, I’m just really good at teaching English literature.

[00:12:13] Like that’s just not, that’s not a plausible story to tell, but there are significant differences in the kinds of careers that are opened up to you, depending on which school you go to. So there’s this sort of weird thing where, you know, in theory we would want educational institutions to be value adding in the sense that you go in there and then they.

[00:12:33] You know, in a almost like factory sense, they pour a bunch of education into your head and then when you exit, your education level is way up. Like that’s the idea. But in practice, The whole college game, especially at the elite level, is not to go to the institution that is the most value adding and gives you the most education for your brain.

[00:12:52] But it’s just, it’s just the competition to get into the schools that have the pipelines to the elite professions and just getting into the school. That’s it. And then you gotta chill out for four years. But that’s, that’s the whole game is just to get into the school, regardless of whether their education is any better than a hundred other universities in the, in the, in this, the

[00:13:12] Jeet Heer: country.

[00:13:12] Well, the value add is the admissions process, right? Like if you’re someone who has both, either the scale set or the more likely financial and social means to get in, then the value add is that you’re able to clear that hurdle. And, and yeah, and, and, and, and once you have that, the, that’s the value.

[00:13:31] And so in some ways, the education is almost besides the point, right? Right.

[00:13:36] Matt Bruenig: I’ve described them before as headhunting firms, if you’re familiar with how Yeah, yeah. The law schools especially. ’cause I went to law school and it’s so clear in that case that yeah, their job is to basically be like what would you say?

[00:13:48] Like, well, headhunting like talent recruitment for Yeah. Firms for the elite law firms. Yeah. Yeah. And that’s all done upfront. Like we’ve already done our job when we’ve done our admissions class and we’ve got the people that you need and come in here in a couple years and hire them out. And that’s it.

[00:14:02] It’s, it’s the recruitment upfront that’s, that’s what makes them valuable to all the parties involved, both the employers and the, the students.

[00:14:12] Jeet Heer: That’s, yeah, no, that’s a good way to look at it. Now, just in terms of reforms, I think, you know, if one’s idea is to have a better Harvard you know, or a better Princeton, there are like sort of things that they could do upfront, right?

[00:14:25] Like they could get rid of legacy, they could get rid of these athletics. Programs they could make it more reliant on standardized tests and not have the essays. And actually that last point, maybe we wanna like emphasize that. ’cause I think this, there’s a real argument on the left and I think there’s a lot of people on the left who are sentimentally attached to the sort of student essay as maybe an avenue towards some form of equity.

[00:14:48] But like I don’t think that that’s how it actually works.

[00:14:52] Matt Bruenig: You know, it’s funny because if we, you go back in time you know, a hundred years, the push for tests was meant to be like an equity type thing, right? Was to eliminate these other advantages people had, right? And that was in an era of more overt discrimination, right?

[00:15:08] So you know, if you were, for example, a Jewish person a hundred years ago, like you were, you were struggling to get into these. Schools, and if it would just test-based, you would have no problem, but they would have just hard quotas against Jewish people. And so, you know, that became a way to cut through all that.

[00:15:22] Say, all right, well let’s just go all on the same level. Sit down, take the test, see who’s best. Yeah. But more recently, of course, we have data that shows. How test scores vary based on, on income and, you know, like you would expect, I guess affluent people score higher than poorer people. But the idea that, that, you know, is I.

[00:15:44] I guess the, the assumption a lot of people move from take from that, like the, the thing they conclude from that is they go, well, the tests are biased and I don’t wanna say the tests aren’t maybe biased a little bit, you know, you can pay for tutoring and all that kind of stuff. But what they’re missing here is that, yeah, people who have, who have.

[00:16:00] Economic advantages are gonna accumulate better educational credentials. That’s just how it is. So, but the idea was, well, let’s, if this is gonna be income stratified, then why don’t we use things like extracurricular activities and like participation and teacher letters and all that kind of stuff where maybe those things could be more balanced, right?

[00:16:19] Because anyone could, could be charitable and join a club and you know, do an extracurricular and whatever. And, and that’ll help. But what we find here in this study is. The exact opposite, that once you control for tests, bringing in these other considerations, just favor the affluent. And that’s been something people have suggested as an al as an alternative point for a long time now.

[00:16:41] But I don’t know, you kind of get people rolling their eyes when you say that. But it makes perfect sense, right? That. Affluent people are the most, have the most information and are like the most strategic about getting into college. That’s why they do things like put their kids in fencing and, and whatever.

[00:16:57] They know what they need to do to get through the process better than other people. And part of that is accumulating these non-academic credentials. And so they’re much more strategic about it than people who, who aren’t. And so that actually tends to favor the rich, not rebalance the scales.

[00:17:15] Jeet Heer: No, that’s absolutely right.

[00:17:16] I, I mean, I think it’s just and if one thinks about it part of the nature of being the rich is that you’re good at gaming the system. Right? And I, I think there’s a historical example which parallels this, which is like in 19th century United Kingdom the civil service jobs initially were like, based on pure nepotism, you could basically hire a position in the East India company if your father had had it, right?

[00:17:37] And then there was a push for civil service reform including. You know, the sort of great liberal reformer John Stewart Mill where they would have testing to be in it. But what happened in the process of nailing this down was that the tests were all designed for, you know, people who went to Oxford and Cambridge.

[00:17:53] So to work in the East India company. You had to know Latin and Greek you know, rather than say sansbury, right? Yeah. And so basically what historians have studied this have found is that like there was like almost no change in personnel of the civil service before and after that, you know, you used to be the sort of children of the elite would get these jobs through nepotism and then after they would get these jobs through test, which were designed for them and them alone.

[00:18:17] So I mean I think that we’ve seen something very similar here where like, you know because they’re the ones with the most access to information and resources to, you know, use that information they’re very good at gaming the system. Yeah. But having said that, I mean like, okay, so we can imagine where like, let’s say you do have a reform movement.

[00:18:35] You get rid of legacies, you get rid of the athletics, you get rid of the letters of recommendation and essays and, and that would, as I understand it, like basically cut down. From like the rich being, the 1% being overrepresented by, you know, 16, 15, 16 points to being overrepresented like 10 times as much.

[00:18:56] Is that roughly right? Like, like it would,

[00:18:58] Matt Bruenig: Yeah, they would still be very overrepresented if you only used academic measures, whether tests or tests and grades. But it would, you know, it would trim it down. I don’t know the precise, yeah. Amount. But yeah, we trim it down a bit.

[00:19:11] Jeet Heer: Yeah. And so, I mean, I, I think in your post this is like one kind of point that you’ve made that, you know, like the reforms that one can imagine, they’re just gonna be at the margins.

[00:19:20] And we’re dealing with a kind of small subset of people, right? Like, you know, like there’s like 4 million people going into, you know college and of that we’re talking about, you know I’m thinking like you know, in the range of. 20,000 or so.

[00:19:35] Matt Bruenig: Yeah, there’s, yeah, there’s 20,000 kids who go into these 12 schools.

[00:19:39] Yeah. And among those 20,000, about 1900 of them are these undeserving rich mm-hmm. That they identified. So 1900 versus, you know, whether you want to talk 20,000 for the whole class are 4 million for the whole class across all institutions. It’s, it’s relatively minimal. And the other aspect of this is that, It’s not like this is an all or nothing like these people are gonna get into college or not get into college.

[00:20:06] It’s just which college they’re gonna wind up in. And this is true of kind of the fixation on these Ivy plus 12 schools in general, which is just the people who are failing to get into these schools, but who are qualified. They’re winding up at. A school that’s only a little bit below it, you know on the rankings and that, that can mean a lot because of the headhunting characteristics and all that kind of stuff.

[00:20:29] But it’s, it’s a lot of just like who should be at the top 50 schools versus who should be at the top 10 schools and there’s 4,000 schools. You know,

[00:20:39] Jeet Heer: so Yeah. That, no, that, that, that, that’s right. So we’re, we’re partially dealing with, you know, like marginal shifts of a small number of people at like a relatively small number of schools.

[00:20:50] But then I, I think that the, the larger question then becomes like, why do these schools have this kind of like, headhunting function and why are they, you know, like Obviously, you know, like an unequal society, you’re gonna have an unequal education system and you’ll have a sort of diversity of ranges.

[00:21:06] But the, the fact is it does actually make a difference. The reason why people care so much about this is that actually if you go to Harvard, there’s a lot of things that open up to you that you don’t get. If you go to a school that’s, Basically just as good as Harvard, but doesn’t have the Harvard name.

[00:21:21] Right. You know, like and this actually, as far as I can tell this is increasing that the, you know, like the people who are on the Supreme Court are now like, you know, much more likely to come from this small court of schools than they were a hundred years ago. Right? Like, yeah, the a hundred years ago you, there were diversity of ways in which one could end up on the Supreme Court.

[00:21:39] Now basically, you know aside from maybe the like they’re all basically coming outta the Ivy League. Right.

[00:21:46] Matt Bruenig: Yeah, I think, I think maybe Amy Coney Barrett’s the sole

[00:21:49] Jeet Heer: accepted. Yeah, yeah, yeah, that’s right. Yeah. She was Notre Dame. Yeah. So I, yeah, no, I, so that’s a kind of so then I think the question becomes like, why would you as a Democratic society permit this.

[00:22:02] You know, permit, like, you know, like having these private institutions with their own, like headhunting function of selecting membership of the elite. And, but these are also private educations that get all sorts of public benefits, right? They’re allowed to run as a nonprofit, which to my mind means that there’s like some sort of, you know, like public interest in them existing.

[00:22:22] But like, why is it in the public interest that like, you know, Harvard gets to select the elite? Like the what’s the logic of that?

[00:22:28] Matt Bruenig: Yeah, no, I, I, I don’t know. And I mean, at the, the, I feel like the left of center has really dropped the ball on thinking about universities more generally, because the fixation has been so much on who could, who can get in and who shouldn’t get in, and really just moving, you know, a few hundred people in and out, whether that’s.

[00:22:47] Affirmative action. Whether that’s this, you know, socioeconomic, you know, again, I don’t, you don’t wanna say that’s unimportant, but there’s also a question of, I mean, we have this question in other contexts as well, which is, should we be focused on who happens to be at the top of this crazy system? Or should we be wondering whether there’s a top at all or whether the top should be squashed down, or is the system itself worth salvaging?

[00:23:12] On top of that, I think people really. You know, and you saw this a little bit with even kind of like the Bernie sandal, Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren proposals. There’s this weird bifurcation in our discussion about the college sector where we only focus on public colleges, right? So it’s like, well, we could make public colleges free, or we should focus on public college as if the private colleges are just like, well, that’s kind of outside of our, I.

[00:23:38] Purview, that’s they’re private and whatever. And you know, the, the socialist in me says, well, wait a minute, wait a minute. And like, those are all our colleges. And yeah, maybe, you know, on paper because of our system, we call them private, whatever. But we need to think about this as a system as a whole. As you point out, these are nonprofit institutions.

[00:23:57] They’re tax exempt. They receive all sorts of federal subsidies in the form of. Pell Grants, other kinds of grants. You know, that’s why they’re subject to, that’s why you could sue them for constitutional violations is because they’re public enough due to the receipt of those funds that, that they need to, you know, not violate the equal protection clause when they’re doing their admissions.

[00:24:17] So yeah, to my mind, let’s bring it, bring all 4,000 of the institutions on the table in front of us and ask ourselves, how do we want this system to run? And I don’t think. Having 12 or 20, or whatever it might be, institutions at the top selecting the future ruling class that’s, that’s not what we want out of an education sector, I wouldn’t

[00:24:38] Jeet Heer: say.

[00:24:38] Mm-hmm. No, no, that’s right. Yeah. And I would just suggest, I mean, you mentioned the left of center. Is kind of skewed on this. And 1, 1, 1 reason is that the ruling class that selected applies to the left of center as well. That the people who go to Harvard are much more likely to end up in left of center policy situations and and therefore overvalue Harvard and overvalue the importance of admissions into Harvard and the yeah, but the system works.

[00:25:04] Matt Bruenig: The system works. They’re able to get their people everywhere, you know, that’s it. Then it just

[00:25:09] Jeet Heer: perpetuates. No. So, so, so if we are thinking about like, okay, you know, it seems like where the logic of all this leads is that we have to, you know, either abolish Harvard or, you know, at least significantly quash its power as a institution that like selects the elite.

[00:25:25] And you know, like one could theoretically imagine ways through that. I think you and I have gone over some of these on Twitter, but, but, but do you wanna like, maybe. You know, just as a speculative thing, like, like let’s imagine, you know, applying eminent domain to like, you know, sort of nationalize Harvard and make it part of, you know, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology or some, or no, that’s a private school, but, you know, like make it part of like a public system you know, change the admissions rules.

[00:25:52] What, what would actually be entailed in having that sort of fight? I.

[00:25:55] Matt Bruenig: Yeah, I mean, when these kinds of questions come up just generally, you know, you always have one of two options. The first option is regulation, right? So you use the fact that they. Do receive public money and you, you can regulate them even without them receiving public money, though that might need to be done on the state level.

[00:26:13] You use that to just bring in rules and force them to follow those rules. And you could create those rules to be whatever you’d like. You could make it a lottery admissions. System where so long as people, applicants get over a certain threshold, maybe of an SS a T score or something like that. So we know that they’re like minimally qualified.

[00:26:32] Then beyond that, it’s just lottery. You could create, you know, really whatever rule you wanted to create as far as admissions are concerned. Regulation always runs into the problem of. They’re slippery. These people are slippery. They know how to get around rules. And so the other option is why don’t we just bring them into the public ownership?

[00:26:52] And I did actually spend quite a bit of time yesterday unexpectedly, based on your prompt, trying to figure out how exactly would you do that? Certainly the federal government and state governments have a right of imminent domain which is you can force Entities to sell assets to you.

[00:27:06] And that applies not just to real estate and real property, but even to entities. These are nonprofit entities, so you can’t sort of force their owners to sell you like Harvard, the corporate entity because they have no owners. So with a nonprofit, which you would end up doing is you would imminent domain all of their assets.

[00:27:28] So the campus, the. You know, the buildings, whatever, whatever they’ve got, you’ve imminent domain. Their assets, imminent domain does require that you pay for them. So you would then weirdly give. Money to Harvard, the kind of corporate entity in exchange for all of its assets, which you can then grab and run as sort of the successor to Harvard.

[00:27:50] And then the Harvard entity would now have all this money in it, including I assume, the endowment, and it would then have to do something with the money. The rule usually is you either have to continue to use it for a tax exempt purpose, transfer it to some other tax exempt entity, some other nonprofit entity, or give it to the government.

[00:28:08] And so I guess it would fall to the, the Harvard board or the Yale board or whatever to figure out what it wanted to do with this big chunk of cash that all of a sudden was on its balance sheet where all of its other assets used to be. But yeah, I mean that would be a kind of like obviously playing fantasy politics here, but.

[00:28:26] I think legally that’s, that’s how you would that’s how you could, you could possibly do that and then bring the 12 schools into a federal system. Or like you said, maybe you could bring it into a state system. A state could do it on its own. Maybe you get one of these states real riled up like Massachusetts and have them, have them grab it.

[00:28:42] I don’t know. But I think you could do it legally. And it’s, it’s, it’s tantalizing to think about for sure.

[00:28:48] Jeet Heer: Well, I, I think that it has to be something that’s at least brought to the table as a, as, as a policy option, because otherwise you’re just stuck with this, you know, like you know, playing with the deck chair of the Titanic, right?

[00:28:59] Like, you’re just Yeah. You so, so I mean, yeah, actually, I, I think it’s very useful to have an argument like, Should Harvard exist? Like

[00:29:07] Matt Bruenig: why we have Harvard. Get ’em scared too. Get ’em scared. Even if you don’t actually pull it off, you know, they, it might calm them down a little bit. I see that sometimes states will when they have private electric utilities, for example, occasionally you’ll see like a governor or a important state legislator say, you know what, we might just, you know, bring in a public utility and, and crush you if you guys don’t cut it out.

[00:29:27] And then, you know, they, they chill out for a little bit. So, you know, there can be advantage in just rattling the. Rattling the cage a little bit, even if you don’t, don’t manage to get all the way there.

[00:29:38] Jeet Heer: So I think rattling the cage is a good point to end at here. Because I, I think that actually sums up a lot of your policy interventions. So I, I wanna thank Matt Budig once again for being here and let’s let’s think more in the future about how we can rattle the cage of Harvard and other elite institutions.

[00:29:56] Sounds good.

[00:29:56] Matt Bruenig: Thanks for having me.