Trump and the Auto Strike—Plus, the Politics of Insecurity

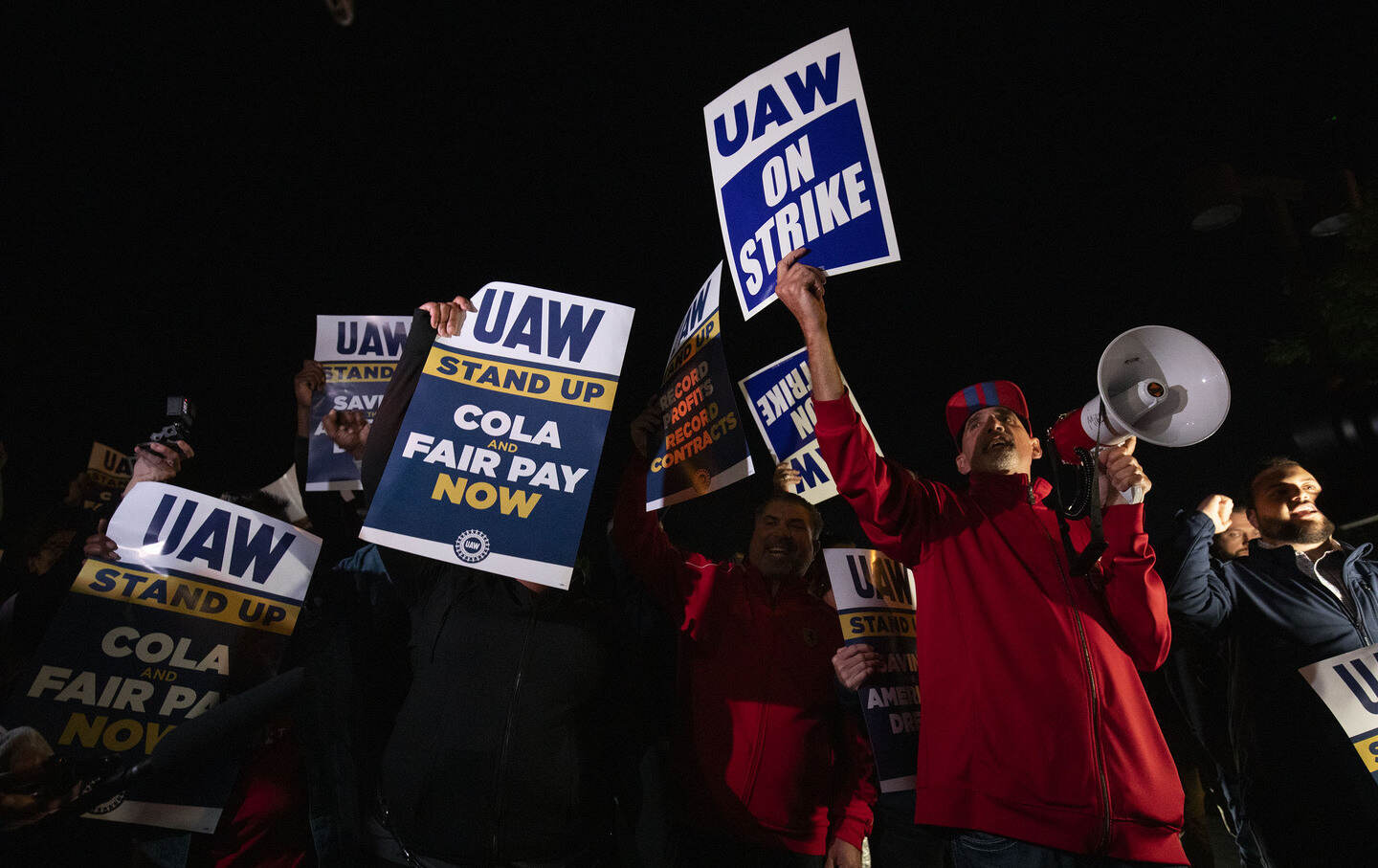

On this episode of Start Making Sense, Nelson Lichtenstein analyzes the politics of the UAW strike, and Astra Taylor talks about “manufactured insecurity.”

Here's where to find podcasts from The Nation. Political talk without the boring parts, featuring the writers, activists and artists who shape the news, from a progressive perspective.

The UAW strike against Detroit’s Big Three is rapidly becoming a major political battle as Donald Trump speaks to auto workers in Detroit, challenging Biden’s massive initiatives for America’s transition to electric vehicles. Nelson Lichtenstein provides historical perspective on what’s at stake.

Also: We face two kinds of insecurity in our lives today, Astra Taylor argues: existential insecurity, the unavoidable issues of life and death, and manufactured insecurity—intended to make workers more submissive to authority. Communal action can do a lot to reduce the second kind. Astra's new book is “The Age of Insecurity: Coming Together As Things Fall Apart.”

Advertising Inquiries: https://redcircle.com/brands

Privacy & Opt-Out: https://redcircle.com/privacy

The UAW strike against Detroit’s Big Three is rapidly becoming a major political battle as Donald Trump speaks to autoworkers in Detroit, challenging Biden’s massive initiatives for America’s transition to electric vehicles. On this episode of the podcast, Nelson Lichtenstein provides historical perspective on what’s at stake.

Also on this episode, Astra Taylor argues that we face two kinds of insecurity in our lives today: existential insecurity, the unavoidable issues of life and death; and manufactured insecurity, intended to make workers more submissive to authority. Communal action can do a lot to reduce that. Taylor’s new book is The Age of Insecurity: Coming Together As Things Fall Apart. She’s on the show to discuss.

Here's where to find podcasts from The Nation. Political talk without the boring parts, featuring the writers, activists and artists who shape the news, from a progressive perspective.

Kamala Harris lost not because Democratic voters switched to Trump, Steve Phillips shows, but because of a massive failure of the Democrats to turn out their base.

Also: In a new episode of “The Children’s Hour,” Amy Wilentz reports on “Lives of the In-Laws” – Ivanka’s and Tiffany’s – and comments also on the rise of Eric’s wife Lara, and about the latest schemes of Ivanka’s husband Jared Kushner.

Advertising Inquiries: https://redcircle.com/brands

Privacy & Opt-Out: https://redcircle.com/privacy

Jon Wiener: From The Nation magazine, this is Start Making Sense. I’m Jon Wiener. Later in the show: existential insecurity and manufactured insecurity–Astra Taylor will explain the difference. But first: the auto strike is rapidly become a major political batttle as Donald Trump announces plans to speak to auto workers in Detroit. Nelson Lichtenstein has our analysis – in a minute.

[BREAK]

JW: Donald Trump’s announcement that he will go to Detroit to speak to striking auto workers turning that strike into a political conflict with enormous implications, both for the 2024 presidential election, and for the transition to a green economy. For an analysis, we turn to Nelson Lichtenstein. He teaches history at UC Santa Barbara, where he directs The Center for the Study of Work, Labor, and Democracy. He’s the author of 16 books, including the definitive history of the UAW, titled Walter Reuther: The Most Dangerous Man in Detroit. His new book just published is A Fabulous Failure: The Clinton Presidency and the Transformation of American Capitalism. He also writes for The New York Times, The L.A. Times, The Guardian, and The Nation. Nelson Lichtenstein, welcome back.

Nelson Lichtenstein: Thank you.

JW: The UAW went on strike last Friday against all three auto companies, GM, Ford, and Stellantis, which is what Chrysler, Jeep and Fiat have become. And then on Monday, The New York Times reported that Donald Trump was going to Detroit next week to speak to striking auto workers. The strike had already raised huge issues about how UAW members might be hurt by the transition to electric vehicles. Now it seems like that may be an issue on which Trump will challenge Biden. So let’s talk first about Biden, and the transition to electric vehicles, and why that’s such a huge issue for the UAW in this strike.

NL: Of course, the Biden administration really renewing an industrial policy that some of the progressives in the early Clinton years wanted, has successfully pushed through Congress billions and billions of dollars of incentives, loans, grants, customer rebates to push forward the transition to electric vehicles. And the auto industry is just gobbling that up. And some $90 billion of new plant and equipment is on schedule. Anyway, it’s actually quite successful. The issue has become: what will be the character of the work, and will they be union members in these new electric vehicle plants, and the battery plants in particular, which are being built throughout the Midwest, the mid-south in particular, and the south? On the table at the negotiations between the auto union and the old big three, they’re the unionized big three, are wages. And I think the union will win some substantial wage increases, and other issues, including getting rid of the tiers, which was very irritating to most workers.

But what’s looming in the background, and getting increasingly important, and Trump is making it more important, is what will be the character of work in these new battery plants. Now, the big three claim, ‘Oh, these battery plants are going to be joint ventures with the Koreans or other East Asian countries. And so they aren’t really even covered by the contract.’ And of course, what they really want is they want to have a lower tier of wages in the EV and the battery plant so as to compete with non-union Tesla, and non-union Toyota, et cetera. The UAW is saying, ‘Look, we’re tired of differential wage levels. We want to get rid of these tiers. We want all the auto workers to make the same amount of money, and you’ve made a ton of money in the past. And we want the auto industry to make a pledge that these new plants will be both high wage and unionized.’

And the politics that comes in is they want the Biden administration to use some of the leverage which is inherent in multi-billion-dollar grants and loans to force that through. Trump, on the other hand, is saying, ‘Oh, that’s not going to happen. It’s going to be lower wages. And some of the new battery plants will be in China or Mexico. So forget the whole thing. Reject Biden. Reject Bidenomics. Reject the Green Transition. Just forget it.’ So it’s a political issue, and a serious one. The UAW leadership hates Trump, but nevertheless, Trump is making that appeal.

JW: And it’s not just the auto industry that is beginning a historic transformation. It’s also the UAW that’s in transformation. Tell us about that.

NL: Well, we had this remarkable democratic movement in the UAW beginning two or three or four years ago. Actually, it’s been there for many years, but it successfully got a new procedure for electing a president, and more a clearly militant, left-wing, younger slate, which won overwhelmingly in the elections that took place last winter. So there is a new leadership, and I think that leadership is reflecting the thirst out there among the membership and among many others for a more aggressive, militant, expansive definition of unionism, and what they want. And I’ve said that I think Shawn Fain’s speeches are a combination of the old legendary Walter Reuther, and Bernie Sanders, and he does it well. He does it well.

JW: Let’s talk about some of the specifics at issue in this strike where the union is asking for a 46% pay hike, plus improved healthcare, and retirement benefits, plus the renewal of cost of living pay raises, as you said, an end to different tiers of wages for the older and the newer workers, the restoration of defined pension benefits, and last but not least, a 32-hour week with 40 hours of pay. Shawn Fain, the new president called the current demands “audacious.” I wonder if you agree with that.

NL: Well, yes, they are. What there has been, and everyone says this, and Biden and Obama say this too, there was a real reduction in actual auto unionized auto worker pay really since the turn of the millennium, and even more so since the Great Recession. In the Great recession, GM and Chrysler went bankrupt.

JW: This is 2007 and 2008, at the beginning of the Obama administration-

NL: Yeah, they went bankrupt. And part of the deal that provided billions in loans to get them back on their feet was that the auto workers took defacto wage cuts. And then subsequently to that, the union, under leadership was actually corrupt, didn’t recoup that. Well now, given this low unemployment and actually a great demand for automobiles, the union wants to recoup some of those concessions. But what’s important about it is to say one of the Achilles’ heels of unionism in the auto industry has been the existence for many decades of these non-union transplants, Toyota, and Nissan, and now Tesla is non-union. And if you’re going to unionize those, you got to go to those workers and say, ‘Look, here’s what we won with a militant democratic union, and you can win stuff too.’ The UAW hasn’t really been able to say that in the past several decades.

So a big wage increase will be a good thing for workers, of course, but also a message to take to the non-union factories. Tesla is particularly important. Tesla’s plant is in Fremont, and this used to be a GM plant, and then a joint venture with Toyota. The workers in the Bay Area are not milquetoast. This is not a milquetoast kind of place. This is not the deep south. This is the kind of place that should be unionized. Now, the labor law is rotten, and Elon Musk who owns the thing as an eccentric billionaire. Who knows what he’s up to, but nevertheless, the thousands of workers there be prime opportunity for the UAW, and if they go to them, and say, ‘Look, here’s what we won. Join us.’

JW: I want to highlight the wage issue. I understand that the starting wage for auto workers before the 2007 crash and the bailout was $19 and 60 cents, and that right now, it’s $18 and 4 cents. In other words, the starting wage for auto workers now is a dollar-fifty less than it was 16 years ago. There’s been some inflation, I understand, which makes the equivalent wage today $29. So asking for that 40% increase is really just keeping up with inflation of what, as you say, what they haven’t gotten since 15, 20 years ago. Meanwhile, one of the big issues for the union in this is executive pay. So if auto workers’ starting pay today is less than in 2007, is that also true of executive pay?

NL: Executives, of course, have gotten 40% higher wages in the last I think four years. The thing I would like to highlight, and I’ve said this other places, is inequality within the working class in some ways is more disruptive, and can create resentment and bitterness because if the person working next to you at the desk or the line is making three bucks an hour more, you know that. That’s intimate. That’s personal, and that can generate, especially in recessionary times, just resentment. And so the UAW properly wants to get rid of those tiers inside the factory so you have equal pay for equal work, which is a canon today.

JW: So the big issue is all the billions of dollars of new electric vehicle plants and battery plants being built right now in Georgia, and South Carolina, and Alabama. These are the non-union states where it’s even harder to organize than in the old industrial states. The strike is not demanding that the new plants be union plants as I understand it. So what exactly is their demand about this huge issue?

NL: Well, they’re demanding that the Biden administration use the leverage it has to force these companies to be neutral in NLRB elections, or to pledge the high wages to begin with when they begin operating the plant. You can condition the loans, things like that. But I would say one thing that we do have in this country all the time are project labor agreements, which are usually in the building trades. So if you’re building a federal building, or even a building with lots of federal support, you often have a deal cut beforehand which says, ‘Okay, this will be built by union labor.’ Well, if it’s going to be built with union labor, you can be operated with union labor. You could extend the idea of a project labor agreement to the operation of the factory itself.

And again, the crucial political importance of this is if these do turn out to be inferior jobs, low wage jobs, well then Trump has a talking point. He can say, ‘What the heck? This whole Green Transition is a scam, which is going to lower the standard of living of American workers, and Bidenomics is a scam.’ So a lot is at stake here.

JW: Trump has already said that the EV transition is going to hurt workers because the jobs are really going to go to China and Mexico, and so he’s going to appeal to the membership of the UAW by attacking the leadership of the UAW. How far do you think he’ll be able to go with that in next week and the weeks to come?

NL: I do think it will fall on deaf ears of a lot, and certainly the leadership is extremely hostile to Trump. They know who he is. But there are some workers. I don’t know what the exact percentage was in the 2020 election, but there was a minority, a substantial minority of UAW members who voted for Trump. I don’t doubt that. I would say one more thing politically, Trump has a lot of allies within the Republican Party on this. Even if they can’t stand Trump, the big opposition to unionizing industrial plants in the south now comes less from the companies themselves, although that’s still there, but from the local political class, because they know that a union in a city like Chattanooga, or some place in Mississippi, or rural Kentucky will be a font of liberal policies, expanding Medicaid, and higher minimum wages, and all sorts of issues that the red state Republicans are against.

So you really have a mobilization when union drives take place in the deep south by the local political class against it. They want the Green Transition to fail. They want unionization to fail because that’ll preserve their monopoly on power in these red states.

JW: On the other hand, people like Brian Kemp in Georgia have been taking credit for the Hyundai super-site battery plant being built outside Augusta that’s going to bring untold thousands of jobs. So he also wants to get credit for economic development.

NL: Right, of course. But they want them non-union, and Hyundai will be non-union, or plans to be non-union, and relatively low wages that don’t disrupt the wage structure of the deep south. Of course, they want the plants. They want them there. Sure, they’re willing to give various kinds of concessions, et cetera, to get them there, but they want them non-union, and they want them, at a wage level higher than McDonald’s, but not as high as Detroit.

JW: One last note. In the last 50 years, there has never been a bigger gap between the public support for organized labor, which right now is at a peak, and public support for big business, which is abysmal. The polls in the last couple of weeks showed 75% of Americans side with the auto workers in this strike, 19% with the companies. That’s the Gallup poll. So this is a good time for the union to be making these demands.

NL: Absolutely. The wind is at its back. There’s no doubt about that. And we have a leadership there which is willing to take advantage of these favorable conditions. That certainly hasn’t always been the case. So yeah, I think it is an exciting moment. The UAW is a smaller and weaker institution than it was during its heyday, but nevertheless, as Walter Reuther said, it remains a vanguard for social transformation and social democratic demands in the United States today.

JW: Nelson Lichtenstein wrote about the auto strike for Jacobin. His new book is A Fabulous Failure: The Clinton Presidency and the Transformation of American Capitalism. Nelson, this was great. Thanks for talking with us today.

NL: Thank you very much, Jon.

[BREAK]

Jon Wiener: Now it’s time to talk about Coming Together as Things Fall Apart. For that, we turn to Astra Taylor. She’s a writer, filmmaker, and political organizer. Born in Winnipeg and raised in Athens, Georgia. We know her best as the Co-Founder of the Debt Collective, a union for debtors with roots in the Occupy Wall Street movement. She writes for The New York Times, The Guardian and The Nation. And her latest book is The Age of Insecurity: Coming Together as Things Fall Apart. We reached her today in Brooklyn. Astra Taylor, welcome back.

Astra Taylor: So glad to be here. Always fun to talk with you.

JW: Previous generations had a lot to make them fearful. The threat of nuclear war, before that, the terrors of World War II. But it seems like insecurity is much deeper now. I think mostly because of the climate crisis, but also because of the next pandemics, rising in equality, the threats of authoritarianism. And you write, the way we understand insecurity, the way we respond to it, is more crucial than ever. At The New York Times, you have a vivid description of how we cope. Could you read that for us?

AT: I’d be glad to. “We work hard, shop hard, hustle, get credentials, crimp and save, invest, diet, self-medicate, meditate, exercise, exfoliate.”

JW: Eloquent. You say there are two kinds of insecurity in our lives today. You call them existential insecurity and manufactured insecurity. Please explain the difference.

AT: I really like what you said. I mean, previous generations have absolutely experienced insecurity, and I argue in the book that it’s a core component actually of the human condition. To be human is to be vulnerable, to be in need of care, from cradle to grave. We are dependent on others. We can be wounded psychologically or physically, and we can die. It’s a bummer, but it’s just–

JW: So true.

AT: That is real. That’s not going to go away. The question is how we respond to this existential fact. I contrast existential insecurity with what I call manufactured insecurity. And manufactured insecurity facilitates the accumulation of profits and power by undermining our self-esteem and our wellbeing. And we see this all over the place. No advertisement will ever say, “Hey, you’re great. You’re enough. You’re perfect as you are. But the world needs changing.” Always wants to make us feel that we’re lacking something. And we certainly see the way that job insecurities twisted on workers so that they’ll be more pliable, more docile, less inclined to strike or ask for more.

So I think insecurity is really actually an essential component of the capitalist economic system, and it’s something we don’t pay enough attention to. We talk about inequality. Actually, insecurity is really central. And now that I wrote this book, I see it everywhere.

JW: You quote a line in your book, our capitalist system creates a life of “everlasting uncertainty and agitation.” Who said that?

AT: Karl Marx. Karl Marx recognized that capitalism is based on instability, volatility, that it has periodic crises. So what I’m doing is adding to that framework and saying the crisis is lived day by day. This slow grind of having, again, your self-esteem pummeled, not knowing if you’ll be able to keep a roof over your head or if you’ll have to leave the community you were raised in, worrying about the next unexpected climate catastrophe. So I’m building on that tradition, but I think in a way that merges the psychological and the political, the emotional and the economic, and that’s really important to me as a thinker and a writer, but also as an organizer.

JW: Now, the defenders of capitalism argue that the underlying cause of job insecurity is not the power of owners over workers. It’s the inevitable result of increasing productivity, making workers more productive through innovation. That’s good for the economy, it’s good for consumers.

AT: The insecurity that workers feel particularly is not a natural phenomenon. It’s something that employers work really hard to maintain. And we saw this after COVID. I mean, we’re still living with COVID, so I actually object to my own periodization there. But it was the sense that workers were gaining too much bargaining power and that there needed to be correction through raising interest rates and through removing the COVID social safety net. This book in a very condensed way, because it’s a short book, and I’m talking about really one chapter of the book gives you a picture very rapidly through the history of capitalism.

Going back to the Enclosure Movement, going back to the 1200s, and essentially looking at the way that people have been made insecure on purpose so that they will have nothing to sell but their labor. This is what happened at the very beginning of capitalism in the Enclosure Movement. And that’s been rebranded. It’s been called Creative Destruction or Disruption. This idea that, as Marx said, “all fixed, fast-frozen relations, all that is solid melts into air.” And this is something that we don’t have to accept. What we need to do–and we being the working class, we being ordinary people–is to recognize that actual security is something that we’re entitled to and that we can reorganize the economy so that it meets our needs, so that we don’t always feel like the floor is falling out from under us.

JW: Yeah, you have some devastating quotes in your new book. How about this one? “Increased insecurity makes workers more fearful of unemployment, more desirous of pleasing their employers through improved performance and higher effort and less apt to quit.” Who said that? Was that Elon Musk? Was that Donald Trump?

AT: It was Janet Yellen, the Treasury Secretary appointed by none other than Joe Biden in a memo written, I think in 1996 or so that inspired Alan Greenspan of all people. I mean, I think this is such an important point she’s making in this memo. She’s saying, wow, “Job insecurity has productivity enhancing benefits.” That’s her phrase. Because workes then are more eager to please. That was precisely the point over the last year or so when the COVID safety net was taken away, a degree of insecurity is very useful to the capitalist economy. It’s actually essential to it. It’s foundational to it. It’s what I’m arguing. Part of the lie I am trying to dismantle is that it’s somehow our fault. And this is why insecurity I think is such an interesting word because it’s very personal. But what I’m saying in this book is it’s also political.

JW: Let’s talk about what is to be done, what we can do, and first of all, what we need more of. You have a great list. We not only need cash to pay the rent and the doctor’s bills. We need connection, meaning, purpose, self-esteem, and R-E-S-P-E-C-T. Do these have to be in short supply like the new Prius?

AT: No. Those are things that are in theory abundant. And as I was writing this, I was struck by the fact that we live in an economic order that makes those things scarce. Why does respect have to be scarce? Why does dignity have to be scarce? Why does rest have to be scarce? These are things that could be abundant if we restructured our society. And what’s one thing manufactured insecurity does specifically in its consumerist variation, is it encourages us to amass money and objects, products as surrogates for these other valuable things and these other forms of collective security that we can actually only really get when we work together.

JW: The progressive political activists and organizers I know focus their work on the principles of equality, freedom and democracy, not really security. You argue that this is a strategic mistake. Please explain.

AT: It’s interesting because I had some ambivalence about the word security, and I think it’s because I came of age in the shadow of the war on terror, and there were two words that were really being corrupted at that moment, democracy and security. And I wrote a book about democracy actually trying to rethink that, mostly for myself. But that’s something that still progressives do. Security falls by the wayside, but security is actually foundational to those other values. When we have security, we can exercise our democratic voice more easily. We can feel secure in our freedom. We can take risks we couldn’t otherwise take. A baseline of security can help us achieve equality because people aren’t falling through the cracks. So I think it’s actually a really essential concept.

JW: Are you suggesting that security should be our number one goal as progressives?

AT: No. Not at all. I think that it is a useful concept. I mean, I’m someone who sees these things as always intertwined. You need equality and freedom to have democracy, but democracy also nurtures those characteristics. These are all in there. But I do think that our drive for security makes sense. Because again, we’re fragile insecure beings. I’d like to have a roof over my head. I’d like to know that the people I love are going to be taken care of if they fall ill. These are totally understandable human desires and this healthy desire for security can be met pretty easily, and I think we should not cede the term to the right wing.

JW: Let’s get concrete here for example, let’s talk about the Debt Collective. You’re Co-Founder of this union of debtors, and it showed you how economic insecurity can inspire people.

AT: So much of my writing these days is inspired by my work as an organizer. And being an organizer I think grounds these philosophical threads that I like to chase. But working at the Debt Collective has really taught me that economic insecurity can cut both ways. I mean, certainly we see the right wing tapping into it and talking to people, claiming to represent the working class, speaking to people’s fears and anxieties, and then misdirecting them and telling them to blame immigrants, blame trans kids and not look at the structure of the economy and not look at the political and economic elites.

But through the organizing with the Debt Collective, I see that financially vulnerable people can transform their insecurity into solidarity and come up with strategies to address their economic dispossession. But what I’m trying to do in this book is widen the frame beyond debtors. Because even people who don’t have debt, who might own a house, might be climbing that ladder of economic mobility, they’re at risk in the world as it’s structured. A single medical emergency can devastate your financial wellbeing. They’re worrying about putting their kids through college. Nobody feels like they can retire in this economy. Of course, there’s the climate. So I’m trying to widen the frame and say, you know what, insecurity affects a lot of us, not just the people who are the worst off. And maybe there’s something – maybe we can find some commonality with that, find some common ground and build a bigger tent to fight for structural changes.

JW: One little thing that’s a telling example, I noticed that the new Teamsters contract for UPS drivers requires that the company turn off the cameras in the brown trucks focused on the drivers. Now, those cameras created a specific insecurity, your sister would understand that.

AT: I had no idea, and I’m incredibly happy that that’s one of their demands. So one of the moments that this idea of manufactured insecurity snapped into focus for me was a few years ago just before the pandemic, my sister was telling me about her job working at this hip Brooklyn cafe, actually just a few blocks from where I am now. And this place has a very retro Parisian aesthetic. And she said that her boss had called, well, she and a coworker were manning the cafe and he told her coworker to stop being so chatty with a regular, even though there was nothing else to attend to, no other responsibilities, no other customers.

And it turned out that there were at least eight security cameras installed in a very small space. And they were not there to make the workers safe from some external threat. They were there so that the workers felt that they could be watched at any moment from any angle by the owner who was at home on his laptop. And they always felt like they were about to be fired, that they were about to do some small thing like be too nice to a regular and then be out of a job and thus not be able to pay the rent, not be able to pay their bills, not be able to survive. And that kind of insecurity, we see this all the time, exactly as you just said, with UPS workers who have a camera on them whenever they’re driving, radiologists who are being tracked by digital bots, computer programmers who have key tracking software installed on their computers. And this is just to escalate that sense of job insecurity that Janet Yellen was praising as a productivity enhancing mechanism.

And if there’s something–one core inside of this book –it is manufactured insecurity reflects a cynical view of human nature. It says that we must be spurred to work out of fear. Fear of the bottom falling out, this distress. It’s incredibly bad for our health. I think it’s bad for our political lives, it’s bad for our souls. But there are other kinds of human motivation we could tap into our desires to collaborate, to care for one another or creativity. And let’s try nurturing those for a while instead of using the stick of insecurity to drive people.

JW: Great. One last thing: we have to ask you about student debt. After the Supreme Court ruled that Biden’s student loan forgiveness plan was not constitutional, Biden quickly said he tried to deliver the relief another way. Where do we stand on that at this point?

AT: The fight is ongoing. I think it’s important to also quote the dissent written by the liberal judges who said that the ultra-conservative majority had violated the Constitution when they struck down President Biden’s initial loan plan. So that is an escalation of the crisis we’re having with the Supreme Court today. It’s a testament to organizing that President Biden at least got up there and said he was going to try a plan B, but he once again is moving slowly. He’s created a rather bureaucratic process to use the Higher Education Act of 1965 to cancel debt.

So the Debt Collective is once again pressuring him to actually use his power in a robust, bold way to add pressure to this process. The Debt Collective has just released the Student Debt Release Tool, which I encourage everyone who has federal student loans to use. Everyone can use it. It takes 10 to 20 minutes to fill out, and it will create essentially an application or memo that is sent to the top brass of the Department of Education. We have had success with this strategy before collectivizing individual petitions and adding pressure on the Department of Education.

So the fight’s not over, and the President still has the legal authority to cancel student debt, and we think he should do so in a bold way and dare the Supreme Court to reimpose the debt instead of letting them govern as unelected officials from the bench. Because again, in the words of three Supreme Court justices, they’re violating the Constitution.

JW: We live in a world of everlasting uncertainty and agitation, made worse by the climate crisis, but recognizing how our insecurity is used against us can be a step toward creating solidarity. Yes, things are falling apart, but in the end, solidarity is one of the most important forms of security we can have. The security of confronting together the challenges we face, that’s what Astra Taylor says. Her new book is The Age of Insecurity. Astra, thanks for this book and thanks for all your work and thanks for talking with us today.

AT: Thanks so much for having me.