Republicans and Obamacare, Again—Plus, Early, Early Bob Dylan

On this episode of Start Making Sense, John Nichols has our political update, and Sean Wilentz talks about the latest release in the Dylan Bootleg series.

Here's where to find podcasts from The Nation. Political talk without the boring parts, featuring the writers, activists and artists who shape the news, from a progressive perspective.

Republicans are about to end Obamcare subsidies, driving up premiums for 20 million people during the year of the midterm elections. How have they managed to end up after all these years with no health insurance plan of their own? John Nichols comments.

Also: Bob Dylan’s earliest recordings have just been released—the first is from 1956 when he was 15 years old—on the 8-CD set ‘Through the Open Window: The Bootleg Series vol. 18” – which ends in 1963, with his historic performance at Carnegie Hall. Sean Wilentz explains – he wrote the 120 page book that accompanies the release.

Advertising Inquiries: https://redcircle.com/brands

Privacy & Opt-Out: https://redcircle.com/privacy

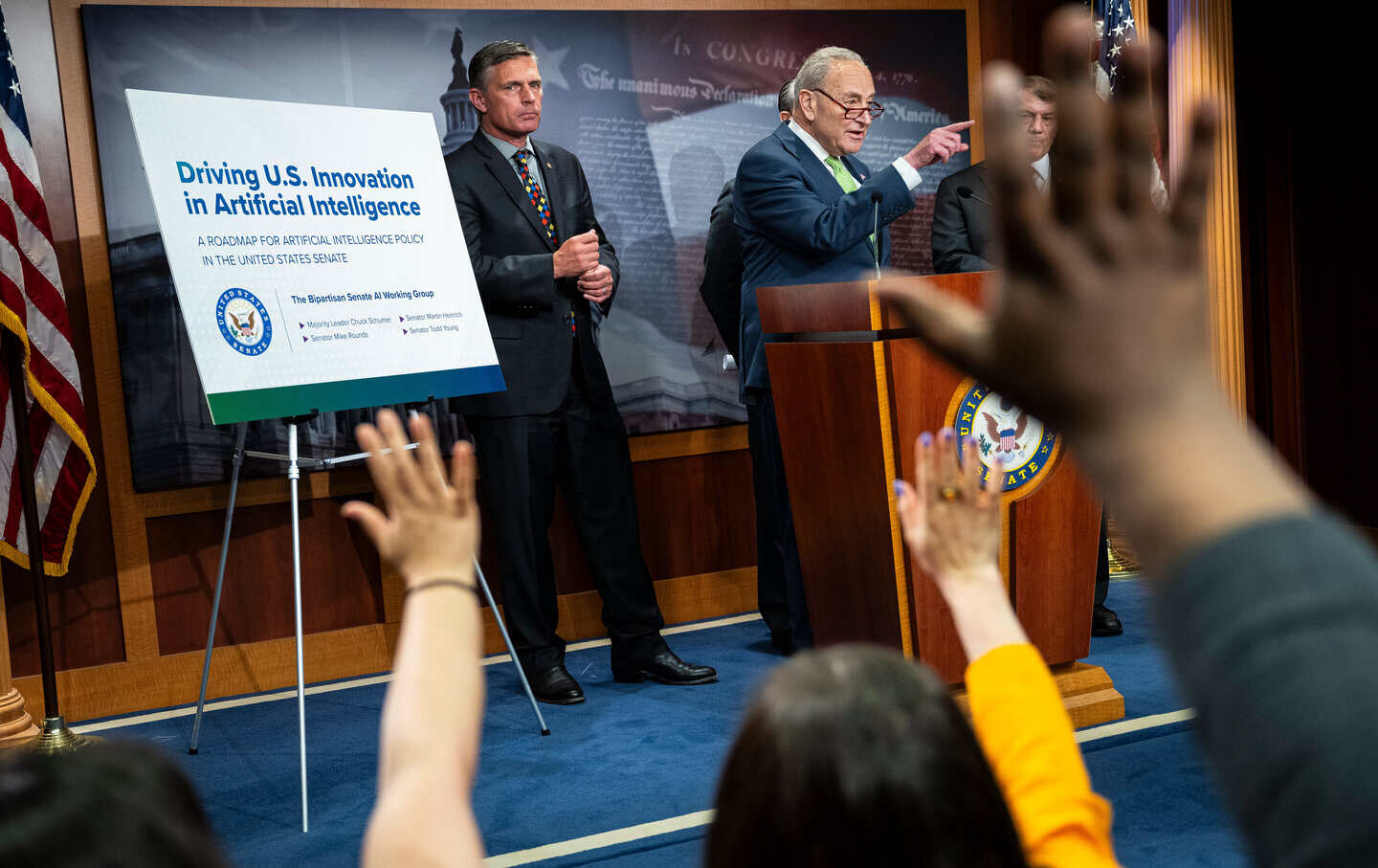

Senate minority leader Chuck Schumer speaks during the Senate Democrats’ news conference on extending expiring Affordable Care Act tax credits in the US Capitol on December 4, 2025.

(Bill Clark / CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty Images)Republicans are about to end Obamacare subsidies, driving up premiums for 20 million people during the year of the midterm elections. How have they managed to end up after all these years with no health insurance plan of their own? John Nichols comments.

Also: Bob Dylan’s earliest recordings have just been released—the first is from 1956 when he was 15 years old—on the eight-CD set Through the Open Window: The Bootleg Series vol. 18—which ends in 1963 with his historic performance at Carnegie Hall. Sean Wilentz explains—he wrote the 120 page book that accompanies the release.

Subscribe to The Nation to support all of our podcasts: thenation.com/podcastsubscribe.

Here's where to find podcasts from The Nation. Political talk without the boring parts, featuring the writers, activists and artists who shape the news, from a progressive perspective.

Tom Stevenson analyzes the latest news and long-term prospects of Trump's Iran war, for both Iran and the US. Tom is a contributing editor for the London Review of Books, where he writes about, among other things, politics in the Mideast.

Also: what news are people getting these days, and where are they getting it? Especially the people we call “news avoidant” & “low information” voters–the ones we want to vote for Democrats in November: what are the big stories for them? Tara McGowan explains– she’s founder and CEO of Courier Newsroom, a digital media company that operates a network of local news outlets.

Advertising Inquiries: https://redcircle.com/brands

Privacy & Opt-Out: https://redcircle.com/privacy

Jon Wiener: From The Nation magazine, this is Start Making Sense. I’m Jon Wiener. Later in the show:

Bob Dylan’s earliest recordings have just been released; the first is from 1956 when he was 15 years old. It opens the 8-CD set ‘Through the Open Window: The Bootleg Series volume 18” –

which ends in 1963, with his historic performance at Carnegie Hall. Sean Wilentz will explain;

he wrote the 120 page book that accompanies the release. But first: Republicans and Obamacare – it’s déjà vu all over again. John Nichols will comment, in a minute.

[BREAK]

Republicans have been wanting to get rid of Obamacare ever since it was launched in 2010. Now, this week, Trump seems to be about to end Obamacare subsidies that are relied on by something like 22 million people. For that story, we turn to John Nichols. Of course, he’s The Nation’s executive editor. John, welcome back.

JN: It is a pleasure to be with you, Jon.

JW: If indeed Republicans end Obamacare subsidies this week, the premiums many people pay will more than double next year. And 2 million, something like 2 million more people will be uninsured next year. And meanwhile, Gallup just released a new poll showing support for Obamacare has now reached its highest level ever.

The Republicans need to pass their own healthcare plan to replace Obamacare basically before January 1st. CNN reports that Trump “worries that voters will blame him for rising premiums. Should he fail to present an alternative” to the Democrats proposal, which is to continue Obamacare subsidies. Trump worries that voters will blame him, CNN says. Do you think they’re onto something here?

JN: Yeah, I do. It’s very interesting that poll number you’ve got where people are increasingly in love with Obamacare, and it brings to mind Joni Mitchell, “you don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone.” And the thing is, Obamacare was always a compromise. There are real flaws in it that many of us would like to see addressed with a single payer Medicare for All healthcare program.

JW: Yes.

JN: However, what we’ve got with Obamacare is now in many states, a reasonably good infrastructure to make sure that people can get the care they need.

Suddenly, everybody is facing this reality that what was a imperfect but functional program and very, very essential for a lot of tens of millions of Americans is now potentially unaffordable. Even people who have healthcare coming from other sources rely on perhaps a rural hospital or rely on an urban clinic. And if you make Obamacare unaffordable and dysfunctional and a substantial number of people opt out of it, that puts the whole healthcare system of the country, not just the people who rely on Obamacare into a very difficult position. So should Donald Trump be worried? Yeah, he should be scared out of his wits. Donald Trump shouldn’t even begin to worry as compared to the 35 to 40 Republicans in the House and four or five Senate Republicans who are up for reelection or in states where they have open seats that are stunningly vulnerable on this issue.

JW: Trump on Monday said, “I want to give the money to the people, not the insurance companies.” And now two Republican senators, Bill Cassidy of Louisiana and Mike Crapo of Idaho have put together a bill to give $1,500 into the health savings accounts of individuals earning less than 700% of the federal poverty level. That bill does not extend Obamacare subsidies, so it would end Obamacare subsidies. And the news at this point, as we speak on Tuesday, as the Republicans are going to vote, that’s going to be the Republican proposal and they’re going to vote on it on Thursday. So how much insurance can you get for $1,500? I look this up. You can get about three months of the worst coverage with incredibly high deductibles, and then you pay for about half of everything after that for three months and then you’re out.

JN: I’m amazed that it could pay for three months.

JW: I asked AI, so who knows?

JN: Yeah, well there you go, that’s the crisis. I can’t imagine that there’s any state in the country where a $1,500 stipend into your health savings account is going to get you anywhere near where you need to be. It creates the fantasy of some resources upfront with the reality that that’s just not going to be backed up. I wouldn’t want to over discuss it though, because I have a feeling that this could get tripped up in the House and it could even get tripped up with the Senate.

JW: There is a second Republican plan. Susan Collins of Maine, Bernie Moreno of Ohio have a plan to extend the Obamacare subsidies for two years, which is pretty much Chuck Schumer’s plan. He wants to do it for three years. Do you think the rest of the Republicans in the Senate will go for Susan Collins and Bernie Moreno’s proposal?

JN: No. But you are with Susan Collins and Bernie Moreno getting into the territory where a handful of Republicans could negotiate with a lot of Democrats. Why would Susan Collins be doing that? I don’t know. She’s running for reelection next year.

JW: I dunno.

JN: That really focuses the attention. Your challenge though is in the House of Representatives because remember, anything that the Senate deals with here, the House is going to have to be working with Trump himself as well. And once again, we kind of get to this point that the Republicans have never liked Obamacare. They are not united in wanting to extend the benefits, but nor are they united on any kind of plan for anything else.

JW: Obamacare became a law in 2010. Republicans have been trying to figure out what to do about it ever since that’s 15 years. Why do you think they’ve never been able to come up with anything?

JN: Because they don’t want this? Go back to the 1930s. The Republicans were griping about social security. Go to the mid 1960s. They were griping about Medicare and Medicaid. In fact, Ronald Reagan kind of made his name complaining about this stuff. This runs deep in the Republican party, not the whole of the Republican party. The party has changed a lot over the years, and it’s a deeply divided party now. Got one grouping that really is populist, another grouping that really is “redistribute the wealth to the rich.” They have such a long history of being united in their opposition to any kind of constructing a safety net that might actually be humane and useful and decent. And they have, I think, finally come to a critical juncture. And this is a big deal. Remember why Republicans opposed Obamacare so passionately back in 2009, 2010, because they said at the time, if you put something in place, people are not going to want to lose it. Now it has finally come to a head and they’re heading into an election cycle where they’re already, he and his party are immensely unpopular and are about to do something that focuses the attention of the entire country. On the long-term and immediate challenge of having Republicans in power, we’re going to see a real test to the Republican party in short order. Can they pull themselves together in a way that keeps them politically viable? And to do that, they have to join with the Democrats to extend Obamacare.

JW: Well, of course, the midterms are 11 months away. As of now, 30 House Republicans have announced they’re not going to run for reelection in the midterms next fall. And Puck News is reporting that 20 more house Republicans may retire in the coming weeks. Of course, some of these people are going to run for senator or governor or something else, but a lot of house Republicans are just throwing in the towel and leaving politics at this point. Why would that be?

JN: Oh, I think they’re looking at political realities all over the country. We have a chaotic, dysfunctional national leadership right now that is a unified Republican leadership. It is not hard to imagine how 2026 could be a disastrous year for the Republicans.

Now, on the surface level you say, well, yeah, but they’ve really worked hard to gerrymander a lot of districts. They have created a situation where they’re hard to beat almost invulnerable because of their corruption of the political process. Except for one thing, Aftyn Behn just ran for the congressional seat in a very gerrymandered Republican district in Tennessee. It became a nationalized raise. Turnout went to midterm levels and the Republicans poured money in, so this is a good test of where we’re at. And Aftyn, Behn moved the numbers by 13 points to the Democratic side. If you look at a 13-point shift to the Democrats and you just spread that out across the country in House and Senate races, it’s not hard if you are a Republican incumbent to look at those numbers and say, “I’ve got a problem.”

JW: This was one of the questions I asked AI: how many Republicans won election in 2024 by less than the 13 points that Aftyn Behn shifted the needle. 44 is the answer. 44 Republicans won by a margin which now seems perhaps not to be a winning margin.

JN: Right? And then here’s one other twist, Jon. The Aftyn Behn race was one where the Republicans got a wakeup call early and they flooded resources into that district. They were countering it. What if you have the wakeup call coming from 40 or 45 districts around the country? And then on top of that, you have it coming in states where there are Senate seats up for grabs and suddenly Republican senators who were thinking, “oh, I don’t have to worry about anything” are saying, “no, no, I’m going to need a whole bunch of that money because I’m not sure I’m going to lose, but I don’t want to risk it.” And this is one of the realities of incumbents that when you start to look at a bad year, they suck up all the money. The more vulnerable candidates get in even worse situations and open seats become even more complicated beyond that. And so I don’t want to create a fantasy here. We are still in very difficult times politically. Donald Trump and his allies will do everything they can to try and win this election, right? They’ve already tried it with gerrymandering and try to get rid of mail-in voting. I mean, there’s all sorts of, their panic is quite evident, right?

So we shouldn’t be naive or unrealistic about this. By the same token, we’re looking at a situation where the wheels really could come off for the Republican party. There are points in America where the economic realities intersect with an election in a way that can really, really move numbers. I think it’s also, Jon, why you’re seeing Democratic recruitment go through the roof. People are, the problem Democrats have at this point in some places is that they’re struggling to keep up with the very credible candidates who are stepping up to run for office in what were previously thought of as very difficult races.

JW: One last thing this week on Tuesday, Trump himself launched a national tour going to Pennsylvania as the first stop to tell voters that he’s the champion of affordability and the working people, of course, his approval ratings have continued to fall. Nothing he does is popular. His approval rating now is lower than any other president at any point in the history of polling. Do you think his approval ratings will go up now because he’s going off on tour?

JN: Look, he’ll draw crowds in places where he goes because he has a base of support. But I’ll always remind you that Barry Goldwater drew crowds in 1964 and George McGovern did in 1972. You can go out and rally your base, but it doesn’t necessarily mean you’re getting anywhere near the majority. And for Trump at this point, unless he goes out there with a radically reworked message, which is not beyond Donald Trump, by the way. And the radically reworked message would be to say, “it’s clear there’s a lot of things we got to do, and I’m ready to do ’em.” Could Donald Trump actually reposition here, theoretically? Maybe. In reality, I don’t think that’s where he is headed. I suspect that you’re going to see long rambling the typical Donald Trump rambling speeches. If that is the case in this moment, I think there is a chance that Trump’s travel around the country could damage his numbers rather than help them. Not because the rambling is a big problem. We’ve seen that all we know, two-hour rally with all sorts of things said. But something else. It is at a point where so many issues are crystal clear. If the President of the United States is going off talking about things that do not seem relevant to the debate, there is a huge danger that a substantial portion of his own base tunes out. But also, that people who are kind of in the middle just say, “well, this is clearly not the answer.”

JW: John Nichols – read him thenation.com. John, thanks for talking with us today.

JN: It’s an honor to be with you, Jon. Thanks for having me.

[BREAK]

Jon Wiener: Now it’s time to talk about early Bob Dylan – from his teenage years as a rock ‘n’ roller in Hibbing, to his folk singing Days in Dinkytown at the University of Minnesota, to the wide, wide world of Greenwich Village in the early sixties. For that, we turn to Sean Wilentz. He teaches American history at Princeton. He’s the author, of course, of many books, including Bob Dylan in America. He’s also co-producer and author of the liner notes for a new CD set, “Bob Dylan: Through the Open Window, the Bootleg Series, volume 18, 1956 to 1963.” The collection includes 48 never-before released performances as well as 38 super-rare cuts. Sean, welcome back.

Sean Wilentz: It’s great to be here, Jon, as ever.

JW: Let me start by saying your so-called liner notes to volume 18 of the Bootleg series is actually a 120-page illustrated book that accompanies seven CDs in a gorgeous two-volume box set released by Columbia. There’s also separately available a two-CD set of highlights, which includes your so-called liner notes.

SW: Actually, not the full text. I think it’s an edited version, but that’s okay.

JW: The story – I want to start at the end. The story you tell here ends on the stage at Carnegie Hall, October 26th, 1963. What did it mean that he was performing at Carnegie Hall?

SW: Carnegie Hall was in many ways, as it still is, the premier venue for any musical performer, orchestral, classical, you name it, in the United States, and this marked a real culmination of his early career.

JW: He opened that concert with a new song, “The Times They Are a-Changin’” – let’s listen.

[MUSIC]

JW: Tell us about “The Times They Are a-Changin’”.

SW: “The Times They Are a-Changin’” as you say, was a brand new song. This was an anthem. I mean, he had probably been best known to this point for a song he’d written a year and a half earlier, “Blowin’ in the Wind.” That was already becoming an anthem of the Civil Rights Movement. This was follow-up to that.

JW: This was October 26th, 1963. Three weeks later, on November 16th, he played McCarter Theater in Princeton, a midnight show.

SW: He sure did!

JW: And he opened that concert with “The Times They Are a-Changin’.” And I’ve got to say, I was there.

SW: You were there! I was going to ask you about that.

JW: Well, my roommate and best friend was also from St. Paul, and we were very proud that a local boy had made it to McCarter Theater. It was a spectacular way to open this concert. I date it as the beginning of the sixties on the Princeton campus.

Anyway, I want to go back to the beginning of your story here; of the story here: teenage Bob Zimmerman in Hibbing, Minnesota in the 1950s. This early Bob was in bands and sang the same songs as a thousand other kids who had bands in the Midwest, and every place else, in the late fifties and early sixties: “Come on baby, let the good times roll.” “I got the blues from my baby down by the San Francisco Bay.” What was his musical world as a high school student in Hibbing?

SW: Well, that world was enormous. It was based in rock and roll, as you say. I mean, his first great hero musically was Little Richard. In his high school yearbook, they say what they predict what your future’s going to be, and his future was that he was going to join Little Richard. He played the piano somewhat more like Jerry Lee Lewis in some ways, but he played it in that raucous way, and he very much admired that – but that was by no means, and rock and roll generally–I mean in ‘56 when Elvis breaks, it changes his life as it changed the life of so many other young people. He was very much at the core. He was just 15 years old when all of this is happening. So he was really at the center in terms of being a listener to the rock and roll revolution.

JW: You emphasize that his musical world was much bigger than rock and roll, much bigger than the top 40.

SW: Yes, you can hear tapes of him talking as a young kid about all the kinds of music he was listening to, saying what he thought about Johnny Cash, for example, and what he thought about this particular – Carl Perkins. He was listening to a lot of different things in part because, up there on the Iron Range, you could get in those days big radio stations from as far away as Shreveport, Louisiana would be broadcasting. And because there was nothing between Shreveport, Indiana and Duluth or Hibbing, Minnesota, you would get those signals so he could get late at night. You could get the music that was coming up from the south and that included country music and included the blues, it included all kinds of things.

The thing about Bob Dylan is nothing is wasted on Bob Dylan. And that was true from when he was a young kid and when he hears something, he imbibes it, he metabolizes, it becomes part of his soul, his musical soul. And the kind of smorgasbord, jamboree, whatever you want to call it, of music that he was getting as a youngster up there in Hibbing. Hibbing seems like it’s very far away, but it was very much in touch, or he made it be in touch with the entire musical world, the popular musical world that was around him.

Including by the way, in Hibbing, he’s listening to things like polka music. He’s listening to Bing Crosby, he’s listening to things that are out there, and it’s all lodging in his ear. It’s not all going to come out right away by any means. He’s going to go through one particular channel after another, but you never know when it’s going to come back out. So that when he’s singing Big Crosby or Frank Sinatra songs later on in his career, this is all part of his musical soul.

JW: Now it’s time for Your Minnesota Moment– that’s news from my hometown of St. Paul. You have on this CD set, what is believed to be the first ever recording of Bob Dylan — recorded in 1956 in my hometown of St. Paul. Bob was 15 years old. Let’s listen: Bob Dylan and two friends; it’s Christmas Eve, 1956 in St. Paul: “Let the Good Times Roll.”

[MUSIC]

JW: “Let the Good Times Roll” — Bob Dylan’s first recording. What do we know about this recording, and how come you were able to get it?

SW: Yeah, the second question I don’t really know the answer to. I mean, I signed on this after the Dylan office had obtained this tape. It was fairly recently.

Bob Dylan had a cousin; a friend, Larry Kegan, and a cousin, Howard Rutman, and they were down in St. Paul at the Terlinde Music Shop. In those days, no matter who you were, you could go up to the counter, pay a buck or whatever it was, and record your own songs. Bob Zimmerman.

Then Bob Zimmerman took a Greyhound bus down from Hibbing to meet his friends, meet up with his friends in St. Paul at this music shop, and they had a little group going. They had been very, very tight at summer camp. They went to the same Jewish summer camp, I think it was Camp Herzl, and so they knew each other. They listened to the same kind of music.

So they had this band, they called themselves The Jokers. There they were in the Terlinde Music Shop, and there was a piano there, which Bob was going to play, and they sang a whole string of, seven or eight of these 30-second cuts of them singing the hits of the day, mostly doo-wop, some rock and roll. So that’s the story really. It’s just a cousin and a friend and they all get together and they sing rock and roll. And it just so happens however, that one of them was going to become Bob Dylan.

Now, if you listen closely to the cut, you can actually hear Bob standing out from the others. He was always the kid who knew slightly more than everybody else, who was willing to take more risks than everyone else, who was willing to get booed on the stage of the Hibbing High School, playing Little Richard songs because he just loved it so much. And he’s very ambitious and he’s afraid of absolutely, he’s absolutely fearless. And so that comes across a little bit on this record too.

JW: After high school, he goes to Minneapolis, and enrolls at the University of Minnesota. Near the campus, there’s a Bohemian district. You call it “a kind of provincial version of New York’s Greenwich Village.” We called it Dinkytown. What did Bob find there?

SW: He found folk music in a big way. Dinkytown was actually something of a center for folk song — Koerner, Ray & Glover were going to come out of there, a very important blues folk group coming out of Minnesota. They were all there. Tony Glover was there, Dave Ray was there, so was John Koerner. So there was a lively folk scene, and it hit Dylan very, very hard. And he talks about having listened to, I think an Odetta record, and he immediately exchanged his electric guitar for a Double O Martin, and he was going to play folk music from then on in.

And then at one point, another friend of his named Dave Whitaker, who was one of the many fascinating characters around Dinkytown, something of a guru around Dinkytown. Dave Whitaker gave him a copy of Bound for Glory, Woody Guthrie’s semi-autobiographical book. It’s embellished, but it’s his life story. And that knocked Bob Dylan for a loop. In fact, he’d just become the Bob Dylan.

He started playing in the coffee houses around Dinkytown; places with names like The Purple Onion and the 10 O’clock Scholar, and that’s where he started. He started his folk career right there, but it was very much with a deep appreciation for both the music and the values and the life and the style of Woody Guthrie.

JW: The big moment of Dylan’s education, his emergence, is the story of his early days in Greenwich Village. He arrives January 24th, 1961. He told his version of those days in his wonderful memoir Chronicles. It’s I think one of the best things he’s ever done.

SW: I agree.

JW: And then there was the recent movie, A Complete Unknown starring Timothée Chalamet does a nice job on those years. But this collection of yours is the definitive musical record of that key period.

When he arrived in the Village, you write, he “dove into a musical maelstrom.” Big question here: what do you see as the most significant moments, the most important influences, the biggest breakthroughs in his first months in the Village?

SW: Yeah. Well, very early on, he came to New York to meet Woody Guthrie, and he did so. Woody Guthrie was then hospitalized. He had Huntington’s disease, but on weekends they would let him out, the Graystone Hospital, let him out to stay with a couple in East Orange, New Jersey. And this place became a little salon of the old kind of popular front era folk singers, including Pete Seeger, and Cisco Houston for a while. And Woody would be there, and everybody would go out there and have this sort of Sunday salon, if you will. Well, Bob Dylan heard about that, and the next thing you knew, he was in East Orange, New Jersey.

But very early on he’s playing at the Cafe Wah?. And this man, Dave Van Ronk, sees him at one point. In Chronicles he says that he met Van Ronk at a place called the Folklore Center, which is also another important spot in the Village world, it’s kind of the citadel of American folk music at this point, run by a marvelous man named Israel Young. At any rate, he connects with Van Ronk and Van Ronk’s music, you can hear it very clearly, has a great deal of influence on not so much Dylan’s style, although he does borrow from Dave, he borrows from everybody as with his repertoire.

And it wasn’t just the folk singers, even. The Greenwich Village in the early sixties consists of artists. It consists of playwrights, it consists of actors, it consists of every artistic movement you can imagine. Jazz was very much on the scene. I mean, Dylan was going to hear John Coltrane before John Coltrane was John Coltrane, Bob Dylan, before he was Bob Dylan was listening to him.

JW: And his influences, if we can call them that, extent beyond music. Like a million other young people in the early sixties, he’s also deeply moved by the Civil Rights Movement in the South, and by its music, and he learns a lot about this from his new girlfriend, a serious artist, and a serious activist.

SW: Yes, Susie Rotolo was his first great New York love, and Susie Rotolo was the daughter of a pair of communists in the city, and she was very politically active. She was working with CORE, the Congress of Racial Equality, at that point, very involved in the Civil rights movement. She has an enormous impact on him, and so that by early 1962, he’s writing songs that have a much harder political edge than anything he had written before. But not with the idea of being a movement person. Susie was a person who would join picket lines. That’s not Bob Dylan. And he’s not going to repeat some other person’s political line, but he’s going to take a story, not unlike the way that Woody Guthrie did, and turn it into a work of art.

JW: It’s at this point that he begins to be known as a singer of protest songs, that people start calling him “the voice of his generation.” And that’s because of the song that you have mentioned, “Blowin’ in the Wind.” If there ever was an iconic song for a new generation, “Blowin’ in the Wind” was it. Your collection features a 1962 recording, the first ever public performance of Blowin’ in the Wind.” Let’s listen.

[MUSIC]

JW: That’s the first ever public performance of “Blowin’ in the wind.” Tell us about this song and this recording. You say that it’s not like other protest songs like, “Which Side Are You On?”

SW: Right, right. I mean, Dylan didn’t want to become a protest singer because he didn’t have all the answers the way that many political protestors seem to have the answers, “you join us and we’re going to change the world.” Well, Dylan wasn’t going to go there. He was much more comfortable telling a story, but “Blowin’ in the Wind” yeah, that was something of a breakthrough. The older political people kind of thought, “what is this? blowin’ in the what? Where? how? What’s blowin’ in the wind?” I mean, Van Ronk said “Jesus, Bobby, what a stupid song.” Because it didn’t have that degree of the concrete political message. It was a much more ambiguous, much more indeterminate. “The answer is blowin’ in the wind.” Well, what does that mean? Is it ever going to come down? What is the answer?

JW: So Dave Van Ronk called “Blowin’ in the Wind” “stupid.” But what did Mavis Staples say?

SW: Ah, well, Mavis Staples hears it and says, “my God, that’s what my father went through.” She doesn’t latch onto the “blowin’ in the wind” part. She takes on the verse itself: “How many roads must a man walk down/before you call him a man?” And she says in a famous interview, she says, “that’s what my father went through. How did this guy understand? How could this guy capture it?” She loved the song. In fact, the Staple Singers recorded the next year,

JW: And then he wrote his masterpiece. We have to talk about “Hard Rain.” Your recording here is from a private recital performance at the Gaslight, September 19, 1962. Let’s listen.

[MUSIC]

JW: “Hard Rain” is an amazing thing. What can you say about “Hard Rain”?

SW: Well, “Hard Rain” kind of comes out of nowhere. People thought it was about the H-bomb. That it had something to do with the Cuban Missile Crisis. It was actually written before the Cuban Missile Crisis. But it’s about a judgment. Something’s going to happen. Something’s going to be judged, maybe by the hand of God, who knows? But the judgment is going to be a very harsh one, and it’s going to lead to these various scenes that he produces. Now, he’s very clearly been reading French symbolist poetry that shows up that affects the words that he’s writing, the imagery that he’s using; It’s very stark imagery.

And then at the end of it all, of course, to present this kind of, I dunno, it’s not a prophecy exactly, but he stands before everyone and says, “I’ll know my song well before I start singing.” And project off the mountainside so that all souls can hear it. I mean, it has this magnificent conclusion to it all that just blows you away. No one had written anything like it before, let alone Bob Dylan.

JW: We hear that song on the album he released May 27th, 1963, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan: “Blown’ in the Wind,” “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Vall.” That also has the unforgettable cover of him with Suze Rotolo on his arm walking through the slush in the Village in July ’63.

A couple of months after that, Bob goes to Mississippi. Just to set the scene here, SNCC had a voter registration project going for more than a year in Greenwood, Mississippi. And this was a music festival to support that. It involved the leaders of SNCC, John Lewis, James Foreman, Bob Moses, and several leading lights of the folk music left, led by Pete Seeger, Theodore Bikel, SNCC’s Freedom Singers. This was held on a Saturday in a field at a Black-owned farm outside of town. About 300 supporters showed up. They had a microphone set up in front of a flatbed truck on a farm field. Bob Dylan sang three songs and culminated with “Blowin’ in the Wind.” Let’s listen.

[MUSIC]

SW: The story of Greenwood is incredible, Jon. I mean, I had not realized what they were going through and the connection with Medgar Evers. Medgar Evers was very involved in the Greenwood movement because he was the head of the NAACP in Mississippi,

JW: In Mississippi.

SW: But the Greenwood scene, they were being killed. They were being shot at.

JW: Yeah. When Bob went to Greenwood, Mississippi, that was just three weeks after Medgar Evers had been assassinated, head of the NAACP in Mississippi, shot in the back in his front yard in Jackson, which is a hundred miles to the south of Greenwood.

Then August 28th, 1963: the March on Washington, a quarter of a million people. The speeches began with civil rights leaders, starting with John Lewis of SNCC, then Odetta, then Peter Paul and Mary sang “Blowin’ in the Wind,” and then Bob Dylan and Joan Baez took the stage and sang a song Bob had just written. “When the Ship Comes In.” Let’s listen.

[MUSIC]

JW: Bob Dylan and Joan Baez singing for a quarter of a million people at the March on Washington, August 28th, 1963, “When the Ship Comes In”: it’s a song of triumph. It’s a prophetic vision of justice and equality that the civil rights struggle will win.

After this, Mahalia Jackson sang, and then King gave his “I Have a Dream” speech. Tell us about Bob at the March on Washington.

SW: By this time, Bob Dylan is a name. “When the Ship Comes In”– there’s another prophetic song that he was a revolutionary song actually. His songs were much more radical actually than the March on Washington’s politics were in many ways, much more like John Lewis say than even Dr. King. It was nationally televised, and Dylan was a Greenwich Village folk singer, very well-known inside those circles. But now he was broadcast nationwide, and he was going to become, regardless of whatever he thought he was going to be doing, he was going to become a kind of national spokesman, just by dint he was having been there, and he was singing songs of extraordinary power.

JW: So this is kind of the end of the story as you tell it in this box set: August 28th, 1963, the march on Washington; October 26th, 1963 is Carnegie Hall.

One last thing. The title of volume 18 of the Bootleg series is “Through the Open Window.” I don’t think that’s a line from a Dylan song. What is it? Where does it come from? What does it mean?

SW: Well, it means that the window was wide open, and you can read about it in the notes. When Dylan showed up in the Village, lots of people were hankering for Bob Dylan. They just didn’t know it yet: the people in the old Popular Front group, they wanted a new Woody Guthrie. Well, Bob Dylan was going to be their new Woody Guthrie. But there’s a whole bunch of other younger people who were looking for someone who was going to be able to take their energy and express it in a different kind of way. Dylan did not seem that at first, he seemed to be an ambitious, somewhat grating young guy from Minnesota who couldn’t play the guitar all that well. But boom, he turned into something, and he transcended everything else that was going on. So in that sense, he arrived at just the right place, at just the right time — when the window was open for him to fly through

JW: Sean Wilentz – he wrote the 120-page illustrated book that accompanies the seven-CD set, “Bob Dylan Through the Open Window, the Bootleg series, volume 18, 1956 to 1963”, the full documented story of Bob Dylan’s earliest recordings and his transformation into the voice of a generation. Sean, thank you for this gorgeous collection – and thanks for talking with us today.

SW: Jon, it’s always a great pleasure to talk to you. It’s great. Thank you.

Subscribe to The Nation to Support all of our podcasts

Support independent journalism that does not fall in line

Even before February 28, the reasons for Donald Trump’s imploding approval rating were abundantly clear: untrammeled corruption and personal enrichment to the tune of billions of dollars during an affordability crisis, a foreign policy guided only by his own derelict sense of morality, and the deployment of a murderous campaign of occupation, detention, and deportation on American streets.

Now an undeclared, unauthorized, unpopular, and unconstitutional war of aggression against Iran has spread like wildfire through the region and into Europe. A new “forever war”—with an ever-increasing likelihood of American troops on the ground—may very well be upon us.

As we’ve seen over and over, this administration uses lies, misdirection, and attempts to flood the zone to justify its abuses of power at home and abroad. Just as Trump, Marco Rubio, and Pete Hegseth offer erratic and contradictory rationales for the attacks on Iran, the administration is also spreading the lie that the upcoming midterm elections are under threat from noncitizens on voter rolls. When these lies go unchecked, they become the basis for further authoritarian encroachment and war.

In these dark times, independent journalism is uniquely able to uncover the falsehoods that threaten our republic—and civilians around the world—and shine a bright light on the truth.

The Nation’s experienced team of writers, editors, and fact-checkers understands the scale of what we’re up against and the urgency with which we have to act. That’s why we’re publishing critical reporting and analysis of the war on Iran, ICE violence at home, new forms of voter suppression emerging in the courts, and much more.

But this journalism is possible only with your support.

This March, The Nation needs to raise $50,000 to ensure that we have the resources for reporting and analysis that sets the record straight and empowers people of conscience to organize. Will you donate today?