Editor’s Note: Reporting for this article was funded by a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

“Felicia Anna” is the nom de Internet of a 27-year-old Romanian prostitute who has worked in one of Amsterdam’s famed window brothels for the last four years. This spring, she launched a blog, Behind the Red Light District, and when I was in Amsterdam reporting on prostitution laws, a Dutch advocate for sex workers’ rights suggested I read it. Anna’s writing, the advocate said, would help me better understand the reality of legalized prostitution—a reality far removed from the lurid tales told by European anti-prostitution campaigners who seek to criminalize the purchase of sex.

Written in English, Behind the Red Light District takes on what Anna sees as the myths propagated by the “rescue industry,” the confluence of radical feminists, conservative Christians and members of law enforcement who seek to save girls from sex trafficking. Legally, Anna would probably be considered a victim of trafficking herself. She had few prospects in Romania, she said, where she could expect to earn 200 euros a month at most. Some friends had promised to help her find a bar or restaurant job in Italy, but it never came through. Finally, at loose ends, she spoke to a couple—an Amsterdam-based sex worker and her boyfriend—who promised that she could make a lot of money as a prostitute in the Netherlands, which legalized pimping and brothel-keeping in 2000. They got Anna started, buying her plane ticket, putting her up in their apartment and helping to arrange the necessary paperwork. In exchange, Anna had to pay them back all the money they spent, “plus a little extra for all the effort they put into it,” she says.

But this was not, Anna insists, an exploitative situation. The couple was kind to her, functioning more as a helpful employment agency than as underworld thugs. The work turned out to be remunerative, and the independence it provided was empowering. “I have a good live [sic], have enough money to do whatever I want to do, and have all the freedom in the world to do what I want, whenever I want to,” she wrote on her blog.

But this was not, Anna insists, an exploitative situation. The couple was kind to her, functioning more as a helpful employment agency than as underworld thugs. The work turned out to be remunerative, and the independence it provided was empowering. “I have a good live [sic], have enough money to do whatever I want to do, and have all the freedom in the world to do what I want, whenever I want to,” she wrote on her blog.

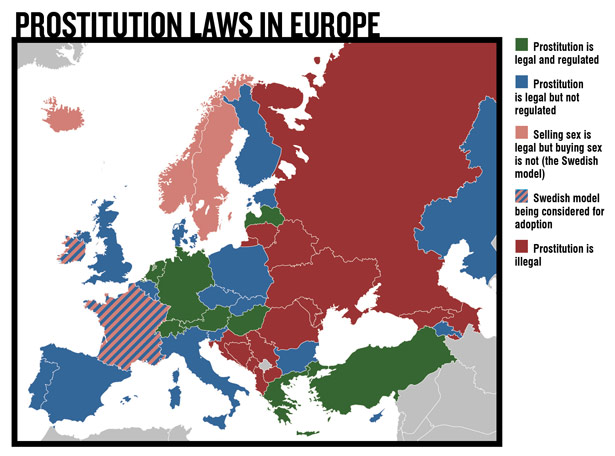

Anna is scathing about the so-called “Swedish model” (also referred to as the “Nordic model”), an approach pioneered in Sweden that bans the buying but not the selling of sex. For the last few years, the Swedish model has been ascendant in Europe. Norway and Iceland adopted it in 2009, and Ireland and France are both considering it, though its future in the latter country is increasingly uncertain after a defeat in a French Senate committee in July. Earlier this year, the European Parliament voted in favor of a resolution calling for Swedish-style laws throughout the continent. Dutch advocates for sex workers’ rights fear that such laws could eventually come to their famously liberal country. The variant of feminism that backs the Swedish model, says Anna, is a “growing cancer for prostitutes.”

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

I e-mailed Anna, and she agreed to meet early on a recent Friday evening at a cafe in central Amsterdam, where she arrived with her Dutch boyfriend in tow. Anna is slight and pretty, with dark hair pulled into a tight ponytail. Her eyes, slanting up above high cheekbones, are ringed with thick black liner, and her eyebrows are painted in a dramatic arch. Given the voice of her blog, I expect her to be tough and sarcastic, but she’s nothing of the sort. She smiles a lot when she speaks, in English that is more broken than on her blog.

How, I ask her, did she become so interested in the politics of prostitution? “Because of my boyfriend,” Anna replies. “I think if I don’t have him, I would still be one of the girls who really doesn’t know what is happening.”

Her boyfriend, who speaks excellent English, has longish brown hair and a hint of a mustache and goatee; he’s wearing a gold-colored chain around his neck and another around his wrist. He works in IT, he says, but never seems to make much money. He met Anna two years ago as a client; before they got together, he lived outside the city because he couldn’t afford an apartment in Amsterdam. Her earnings—about 300 to 400 euros per shift, which can run anywhere from four to ten hours—are more than five times as much as his.

As we talk, it becomes clear that the voice of the blog is at least as much his as hers. In conversation, he compares the Swedish model to Prohibition in the United States, a point also made on Behind the Red Light District. And while the online Felicia Anna says she’s been endangered by a client only once, the Felicia Anna sitting across from me says she’s had to call the police two or three times. Nor does she feel that she can call for help every time a client gets aggressive and starts demanding his money back: “You can’t call always the police, because sometimes then you have to call almost the whole night.” Her boyfriend chimes in to compare it to working late at night at a bar. “You can also get drunk guys late at night,” he says. “You can also have problems with them.”

When I mention that Behind the Red Light District sounds like him, Anna tells me: “He help me a lot with it, because I work in the nighttime and I have to sleep, too. And I have my own stuff that I have to do—cleaning the house, shopping, sometimes cooking. I can’t do everything by myself.”

Basically, her boyfriend adds, “she dictates what I have to write, and I kind of fill in, smooth out the story line.”

* * *

There are two dominant story lines about prostitution in Europe, an issue that has feminists around the world fiercely divided. The first is that full legalization—the approach pioneered by the Netherlands and adopted by Germany in 2002—has failed to curb the abuses associated with prohibition. Trafficking has increased, organized crime has grown more powerful, and conditions for women in the sex industry have worsened. “Legalization sounds good,” says Mary Honeyball, the British MEP behind the European Parliament resolution on the Swedish model. “You want to have a safe environment for the women working. Often, people don’t go behind that to what actually goes on, which is trafficking and other criminal activities.”

The second story line is that the real failure belongs to the Swedish model, which has made life more hazardous for prostitutes by increasing the stigma and driving the work underground. “It’s like saying you can still bake breads, but no one can buy them from you,” says Nadia van der Linde, coordinator of the Red Umbrella Fund, an Amsterdam-based organization that makes grants to sex workers’ rights groups worldwide. “Sex workers have no jobs if there are no clients. The result is that those women, men and trans who are in sex work, they are being put into a more dangerous position because they can’t work out in the open.”

The second story line is that the real failure belongs to the Swedish model, which has made life more hazardous for prostitutes by increasing the stigma and driving the work underground. “It’s like saying you can still bake breads, but no one can buy them from you,” says Nadia van der Linde, coordinator of the Red Umbrella Fund, an Amsterdam-based organization that makes grants to sex workers’ rights groups worldwide. “Sex workers have no jobs if there are no clients. The result is that those women, men and trans who are in sex work, they are being put into a more dangerous position because they can’t work out in the open.”

With the laws of many countries at stake, this is far more than an academic debate, and its implications stretch beyond Europe. In Canada, where the Supreme Court struck down the country’s anti-prostitution law last year, the government is currently proposing a bill based on the Swedish model. Initiatives focused on the demand side of prostitution have even taken off in the United States, though here that tends to mean increasing penalties on johns without decriminalizing sex work.

So does the Swedish model work? I went to Sweden and the Netherlands to find out. After talking to sex workers, politicians, cops, activists and others, my uncomfortable conclusion is that both narratives about European prostitution are true. The answer to the question of which law better protects women—full legalization or the criminalization of demand—is as much ideological as empirical. It depends on whether you see Anna as a trafficked, exploited woman mouthing sex-industry propaganda, or as a person with agency making the best choices she can given her constrained circumstances. It depends on how much regulation you’re willing to accept in the name of gender equality, and ultimately whether you think making it harder for some prostitutes to work is a worthwhile price to pay for reducing the number of women in prostitution overall.

Put another way, the Swedish law works, but at a cost to some of the people it purports to help.

* * *

In the center of Amsterdam’s red-light district, just in front of the Gothic Oude Kerk, or Old Church, there is the statue of a woman cast in bronze. Belle, as the figure is known, stands proud, with hands on her hips and her chest thrust out. A small plaque at her base reads Respect Sex Workers All Over the World.

Belle was erected in 2007 thanks to the activism of Mariska Majoor, 45, a former window prostitute who now runs the Prostitution Information Center, a storefront in the red-light district where visitors can learn about the neighborhood, buy souvenirs or have a snack at a small vegetarian cafe. Majoor is a fierce advocate for legal prostitution, which she sees as a social good rather than simply a necessary evil. But she also readily admits that the lives of prostitutes in the Netherlands have not improved since the law was liberalized fourteen years ago.

At the time, the idea was to bring the business out of the shadows. Brothels were already tolerated, and the authorities believed that by legalizing them, they could better regulate what went on, fighting trafficking and organized crime and protecting the rights of sex workers. A 2007 report by the Dutch Ministry of Justice states: “In general, the starting point used for policy is that the amendment of the law should result in an improvement of the prostitutes’ position.” But that is not what happened, according to the report, which found that “the prostitutes’ emotional well-being is now lower than in 2001 on all measured aspects, and the use of sedatives has increased.”

A big part of the problem is economic. Particularly with the expansion of the European Union, a growing number of women from Central and Eastern Europe moved to the Netherlands to work as prostitutes, creating increased competition. For those who work in the windows, the prices to rent a room for a single ten-hour shift have gone up. It’s now about 85 euros in the less desirable areas around the Oude Kerk, where older, heavier black and brown women work, and 150 euros or more in the busier streets, where younger, thinner, lighter-skinned girls—mostly, like Anna, from Eastern Europe—await their customers. The price for standard sex, though, has remained the same for well over a decade: 35 euros in the cheaper areas, 50 euros in the most desirable. Women need to have sex with at least three men just to break even on each shift, and sometimes they finish owing more than they’ve earned.

“It’s still possible to make good money, but it’s not as common anymore as it used to be,” says Majoor. “And for some women, especially the women in the Old Church Square, it can be very difficult to even make enough money to pay the rent.” Some of these women, she adds, “stay in the business even though they make a small amount of money because they are used to this and don’t know what else to do, or they don’t want to do something else, or they think they don’t have any other option.”

Pro-prostitution advocates say that part of the problem lies in the fact that the Dutch policy isn’t liberal enough. Places are licensed rather than people; the licenses belong to the brothel owners, not the prostitutes themselves. The idea was to make the owners more accountable for conditions in their establishments, but in practice it’s given them a legal monopoly. Meanwhile, in recent years, Amsterdam’s government, embarrassed by the city’s seedy reputation and its role as a hub for organized crime, has started buying up window brothels and turning them into chic restaurants and studios. Eventually, the plan is to close almost half of them. “So the pressure on the windows that are left becomes higher and higher, and the landlords have raised the rents,” says Majoor.

As the number of windows has declined, the competition for them has become fiercer. Women will often pay even when they’re not using them so as not to lose their spots. Anna explains that one reason she has no savings after four years of work is that she suffered complications after her second breast augmentation. She was out of work for almost three months, and during that time she had to continue to pay 155 euros a day for her room.

Of course, you don’t need a window to sell sex in the Netherlands; only about a fifth of the country’s prostitutes work that way. According to scholar Ronald Weitzer, author of Legalizing Prostitution: From Illicit Vice to Lawful Business, 25 percent work in other sorts of brothels, 50 percent work as out-call escorts or at home, and 1 percent work on the street, often in designated streetwalking zones that exist in Utrecht, Eindhoven and Arnhem. (Elsewhere, street prostitution is illegal.)

The windows, however, have certain advantages. Although a 19-year-old was stabbed to death in her window room in 2009, window prostitution is generally considered safer than other forms. Each room has a panic button, with lots of people nearby ready to come running when it’s pressed. Further, says Anna, “you can choose your own customers,” appraising them before letting them in. (She says, unapologetically, that she refuses to work with Moroccans, drunk men or men who look older than 50.)

But while more windows might ease some of the pressures on prostitutes, they would do nothing to raise the price for sex. For that, there would have to be either fewer women working in prostitution or more labor organization. Some writers and activists have hyped the Red Thread, the Dutch sex workers’ trade union, but the truth is that it never had the power to negotiate with brothel owners or set prices, and it went bankrupt in 2012 when the government funding that had sustained it dried up.

But while more windows might ease some of the pressures on prostitutes, they would do nothing to raise the price for sex. For that, there would have to be either fewer women working in prostitution or more labor organization. Some writers and activists have hyped the Red Thread, the Dutch sex workers’ trade union, but the truth is that it never had the power to negotiate with brothel owners or set prices, and it went bankrupt in 2012 when the government funding that had sustained it dried up.

“Sex workers in the Netherlands don’t want to be united,” says Alexandra van Dijk, the Red Thread’s former director. Almost all of them are foreigners who simply want to be left alone, she adds, and can rarely be induced to come to meetings. “They don’t want to speak out with one voice, so [that] kind of union [is] not possible in the Netherlands.” Indeed, although Amsterdam has traditionally been a hub for sex-worker activism, there’s actually a stronger sex workers’ organization in Sweden.

Meanwhile, even as things have gotten harder for sex workers who are in the industry voluntarily, there’s evidence that a significant number of women in the Netherlands have been forced into prostitution against their will, or forced to work in conditions not of their choosing. It’s very hard to say how many: “At the moment, there are no reliable figures available for the total number of prostitutes in the Netherlands,” according to a report by the Dutch National Rapporteur on Trafficking in Human Beings and Sexual Violence Against Children. “Evidently, some prostitutes are exploited, but because of the hidden nature of both human trafficking and prostitution, it is difficult to say how large this proportion is.”

The minimum estimate, however, is in the hundreds. The National Threat Assessment on Organized Crime estimated that 20,000 people worked in prostitution in 2012, the vast majority of them women, with at least 800 trafficking victims. The real number is likely higher, the assessment warns, though how much so is hard to say given the victims’ hesitancy to talk to the police.

As Felicia Anna’s case shows, defining “trafficking” can be politically fraught; there is a gray area between absolute exploitation and total free agency. “Most cases of trafficking are not the media-popular story of somebody being forcibly taken out of their home and forcibly chained to a bed,” says the Red Umbrella Fund’s van der Linde. “In my experience, most cases of trafficking are about women who were actually already working as a sex worker but decided to work somewhere else as a sex worker, and came into a situation where they faced some form of exploitation.”

However they ended up in the country, some women working as prostitutes in the Netherlands are being coerced. Majoor is no abolitionist, but her off-the-cuff estimate is even larger than that of the National Threat Assessment. “I think between 5 and 10 percent of sex workers are actually trafficked,” she says—which, given 20,000 prostitutes in the Netherlands, would mean somewhere between 1,000 and 2,000 people.

Academic evidence suggests that trafficking is exacerbated by legalization. A 2012 article by the scholars Seo-Young Cho, Axel Dreher and Eric Neumayer, published in the journal World Development, concluded that “countries with legalized prostitution have a statistically significantly larger reported incidence of human trafficking inflows. This holds true regardless of the model we use to estimate the equations and the variables we control for in the analysis.”

This can seem counterintuitive—shouldn’t legalization reduce the role of force in the industry, since it allows more women to enter sex work legally? The explanation, according to Cho, Dreher and Neumayer, is that while more women enter prostitution voluntarily in a legal market, the increase in the number of clients is even greater. Demand outstrips supply.

* * *

Sweden, it seems, has figured out how to curb that demand. In 1999, it undertook what was then a radical experiment: banning the buying but not the selling of sex. The Sex Purchase Act was premised on the idea, common to a certain strain of radical feminism, that prostitution is fundamentally inimical to gender equality. “The legislative proposal stated that it is shameful and unacceptable that, in a gender-equal society, men should obtain casual sexual relations with women in return for payment,” stated a government review of the law in 2010. The penalties range from fines to six months’ imprisonment, though to date no violator has been locked up.

Studies suggest that the percentage of men buying sex has declined, from 13.6 percent in a 1996 survey to 8 percent in 2008. No one knows precisely how the law has affected the number of prostitutes in Sweden, in part because its passage coincided with the coming of the Internet, which changed the way the market works. Street prostitution is clearly way down. The Swedish Ministry of Justice estimates that it’s been halved since 1999, and walking around Malmskillinsgatan—a raised street in the center of Stockholm that’s as close to a red-light district as the city has—that seems like an understatement. At 10:30 on a recent Wednesday night, it was largely dead. There was a lone Thai massage parlor, but it had closed at 8:00. A storefront that looked like it was once a porn shop—a sign touted books, magazines and “video-show”—was shuttered.

After a half-hour of walking up and down the street, I finally saw a woman slowly strolling by in tattered tights. She told me she didn’t speak English, and a few minutes later I saw her walk off toward a nearby park with a man. A few more women appeared after that; by 1 am, I’d counted eight. “Before the law was introduced, on an ordinary night, you could have eighty women walking that street,” says Simon Häggström, the detective in charge of the Stockholm police’s prostitution unit.

To some extent, this is just a sign of sex work moving online and indoors, yet there are data to suggest that there’s still less prostitution overall than there would be without the law. The government review, for example, found more Internet prostitution in neighboring countries than in Sweden. It’s possible to conclude, it asserted, “that the reduction of street prostitution by half that took place in Sweden represents a real reduction in prostitution here and that this reduction is also mainly a result of the criminalization of sex purchases.”

Anecdotal evidence from websites where patrons of prostitutes trade advice and reviews back this up. On the International Sex Guide site, for example, a man planning a trip to Sweden asked for tips, only to be dissuaded by other posters. “Bros, don’t waste your time looking for anything. Mongering is illegal and totally dead in Sweden,” said one. (“Mongering” is slang for buying sex.)

The price for sex with a prostitute in Sweden, meanwhile, is widely understood to be the highest in Europe. “The minimum price here is 150 euro,” says Häggström. “Prices are higher because we have a much lesser amount of persons in prostitution compared to the legalized countries.” Not only do Swedish prostitutes make more money than their colleagues in other countries: thanks to lobbying by sex-worker activists, they also have access to the country’s generous welfare state, including sick leave and parental leave. And they’re safer than sex workers elsewhere: not a single prostitute has been murdered on the job in Sweden since the law was introduced.

The price for sex with a prostitute in Sweden, meanwhile, is widely understood to be the highest in Europe. “The minimum price here is 150 euro,” says Häggström. “Prices are higher because we have a much lesser amount of persons in prostitution compared to the legalized countries.” Not only do Swedish prostitutes make more money than their colleagues in other countries: thanks to lobbying by sex-worker activists, they also have access to the country’s generous welfare state, including sick leave and parental leave. And they’re safer than sex workers elsewhere: not a single prostitute has been murdered on the job in Sweden since the law was introduced.

So from a feminist point of view, what’s not to like? The answer, sex-worker advocates say, is all about stigma. “The Swedish model really ups the stigma,” says Pye Jakobsson, the co-founder of the Rose Alliance, a Swedish sex workers’ organization with approximately 150 members, funded by the Open Society Foundations and the Red Umbrella Fund. “And stigma affects absolutely everything.”

The 2010 government review acknowledged this, albeit in unsympathetic terms. “People who are currently being exploited in prostitution state that the criminalization has intensified the social stigma of selling sex,” it said. “They describe having chosen to prostitute themselves and do not consider themselves to be unwilling victims of anything. Even if it is not forbidden to sell sex, they feel they are hunted by the police. They feel that they are being treated as incapacitated persons because their actions are tolerated but their wishes and choices are not respected.”

Then, a few sentences later, it said: “For people who are still being exploited in prostitution, the above negative effects of the ban that they describe must be viewed as positive from the perspective that the purpose of the law is indeed to combat prostitution.”

This willingness to stigmatize sex workers can have deeply punitive effects. Jakobsson says she personally knows four people who have lost custody of their children because they work as prostitutes. One of these cases, involving a Rose Alliance board member called Petite Jasmine, received international attention last year.

In 2012, a Swedish district court awarded custody of Jasmine’s two children to her former partner, a man with a history of violence, because she was seen as inherently self-destructive and untrustworthy because of her work. In 2013, while she was fighting to get her kids back, Jasmine had a supervised visit with them in a house that social services used for such meetings. As Jakobsson tells the story, Jasmine ran into her ex and their kids on the bus on the way there, and they began to fight. Arriving in tears, she sat on the front steps with the supervising social worker, trying to calm down. Meanwhile, the kids’ father walked through the front door and went into the kitchen. He came out with a kitchen knife and stabbed her thirty-one times, killing her.

“For us, it was so clear: stigma kills,” says Jakobsson.

Jasmine’s case was extreme, but prostitutes in Sweden also face more routine forms of oppression. When the Rose Alliance surveyed Swedish sex workers about their chief worries—offering choices including violence from clients and sexually transmitted infections—the most common answer was prejudice from authorities. One constant danger, says Jakobsson, is eviction—a result of the broad application of the country’s anti-pimping law, which makes landlords fearful of any arrangement that can be construed as profiting from prostitution. Of the alliance’s nine board members, three have been thrown out of their apartments.

Beyond the dangers created by the law, Jakobsson sees the assumption that sex workers are all victims as fundamentally degrading. Now 45, she retired from prostitution two years ago, after working for twenty-six years in seven countries. To her, sex work is simply another form of work and should be subject to the same labor laws that govern other industries. That means, among other things, treating sex trafficking as a problem of bonded labor rather than an inevitable outgrowth of prostitution.

“The framework we use when we talk about trafficking for sexual exploitation doesn’t have to be different from the framework we use for other sorts of exploitation,” she says. “Our gut feelings might tell us it’s different, it’s terrible—but for me as a former sex worker, actually, I’d rather be trafficked for sexual purposes than to pick berries in the north of Sweden. But that’s me—most people would disagree and say the other way around. What I’m saying is that there are good legal frameworks. Why don’t we use them?

* * *

This is ultimately where every discussion of prostitution law seems to end up: torn over the question of whether sex work can ever be just a job. The overwhelming consensus in Sweden is that it cannot, whatever people like Jakobsson may say. “You have to lift your eyes from this individual perspective,” says Johanna Dahlin, organizational secretary of the Swedish Women’s Lobby, an umbrella group of Swedish women’s organizations. “How can a few persons’ right or freedom to sell sex stand above the vast majority of women that are trafficked and exploited in prostitution?”

Her colleague, program manager Stéphanie Thögersen, adds that it’s also about the principles underlying Swedish society. “Do we want a society where it’s OK to buy another person?” she asks.

Talking to Swedish feminists, I heard variations on these points again and again. “We don’t base our legislation on individuals’ experiences; we base it on the society we want,” says Olga Persson, secretary general of the Swedish Association of Women’s Shelters and Young Women’s Empowerment Centres. Persson, a fierce supporter of the law, has also lobbied in Europe for Honeyball’s resolution. She finds arguments about freedom and agency in regard to prostitution almost unintelligible, particularly given her work with the battered women in her group’s shelters, some of whom have been involved in selling sex. “If Pye thinks it’s harmful to herself and her friends, we have a lot of voices which are saying the opposite,” she says. “Sometimes you have to talk to survivors, instead of the ones who are in the industry right now.”

By “survivors,” Persson means people who have escaped forced prostitution. It’s not easy, however, to find such people in Sweden. When I ask Persson if she knows of anyone I should talk to, she replies, “We don’t really have that tradition in Sweden—these individual voices. We come together and speak as a group.” In other words, experts like Persson will speak for those worth listening to.

Naturally, Jakobsson and her colleagues at the Rose Alliance find this attitude maddening. Yet Swedish collectivism has also created one of the most gender-equal societies the world has ever known, and Swedish feminists generally see the prohibition on buying sex as a crucial element of that. Indeed, they often speak about it with a sort of missionary zeal, and they are eager to spread the good word to other countries. “The most important thing is that it’s based on an understanding that all women in prostitution are vulnerable, and that the state is obliged to protect them,” Persson says. Whether all women want that protection is almost beside the point.